When a stone sits on the Earth’s surface, cosmic rays quietly pepper it, leaving behind rare isotopes like tiny time stamps. Bury the stone deep enough, and that cosmic “printing press” shuts off. From there, those isotopes decay in a predictable way. In geology, that is as close as you get to a stopwatch.

That stopwatch, along with two other independent clocks, has helped researchers build a sharper timeline for ‘Ubeidiya, an early prehistoric site in Israel’s Jordan Valley. The site has long mattered to anyone trying to map how early humans moved beyond Africa. A new study argues the site is at least 1.9 million years old, older than many past estimates and among the earliest known records of early humans outside Africa.

The work was led by Prof. Ari Matmon of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Prof. Omry Barzilai of Haifa University, and Prof. Miriam Belmaker of the University of Tulsa. Their approach leaned on three dating methods that ask the same question in different ways: how old are the sediments and artifacts in one key layer, known as unit I-26?

‘Ubeidiya has drawn attention for decades because it contains stone tools and animal fossils together, including a mix of African and Asian species, some now extinct. The stone tools include large bifacial pieces tied to the Acheulean tradition, alongside earlier-style technologies that some researchers have compared to Oldowan.

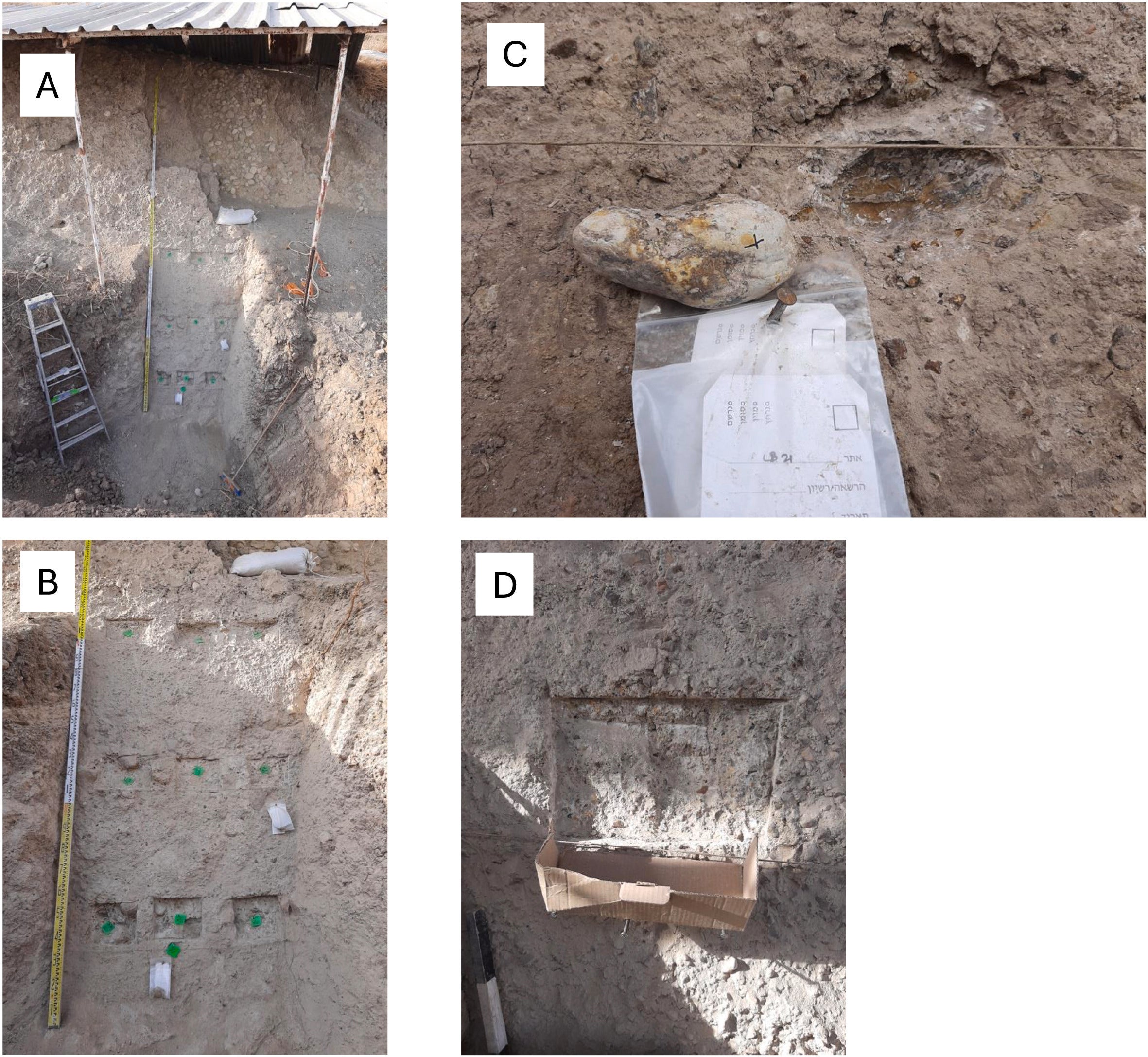

For years, most estimates put ‘Ubeidiya between 1.2 and 1.6 million years old, but those ages rested on relative chronology. This team went back, reopened part of an old trench, and resampled the site with a tighter set of constraints.

The first clock came from magnetism locked into lake sediments. As sediment settles, magnetic minerals align with Earth’s magnetic field. Since the planet’s magnetic field flips polarity over geologic time, those alignments can be matched to a global reversal timeline.

In Trench Ia, the team collected 260 paleomagnetic samples from 54 horizons across a 35-meter sequence, including unit I-26. Only 62 samples passed the study’s quality criteria, largely because many were overprinted after the layers tilted. Still, the usable record pointed strongly in one direction: nearly all samples showed reversed polarity, with just two normal-polarity samples about 14 meters above unit I-26.

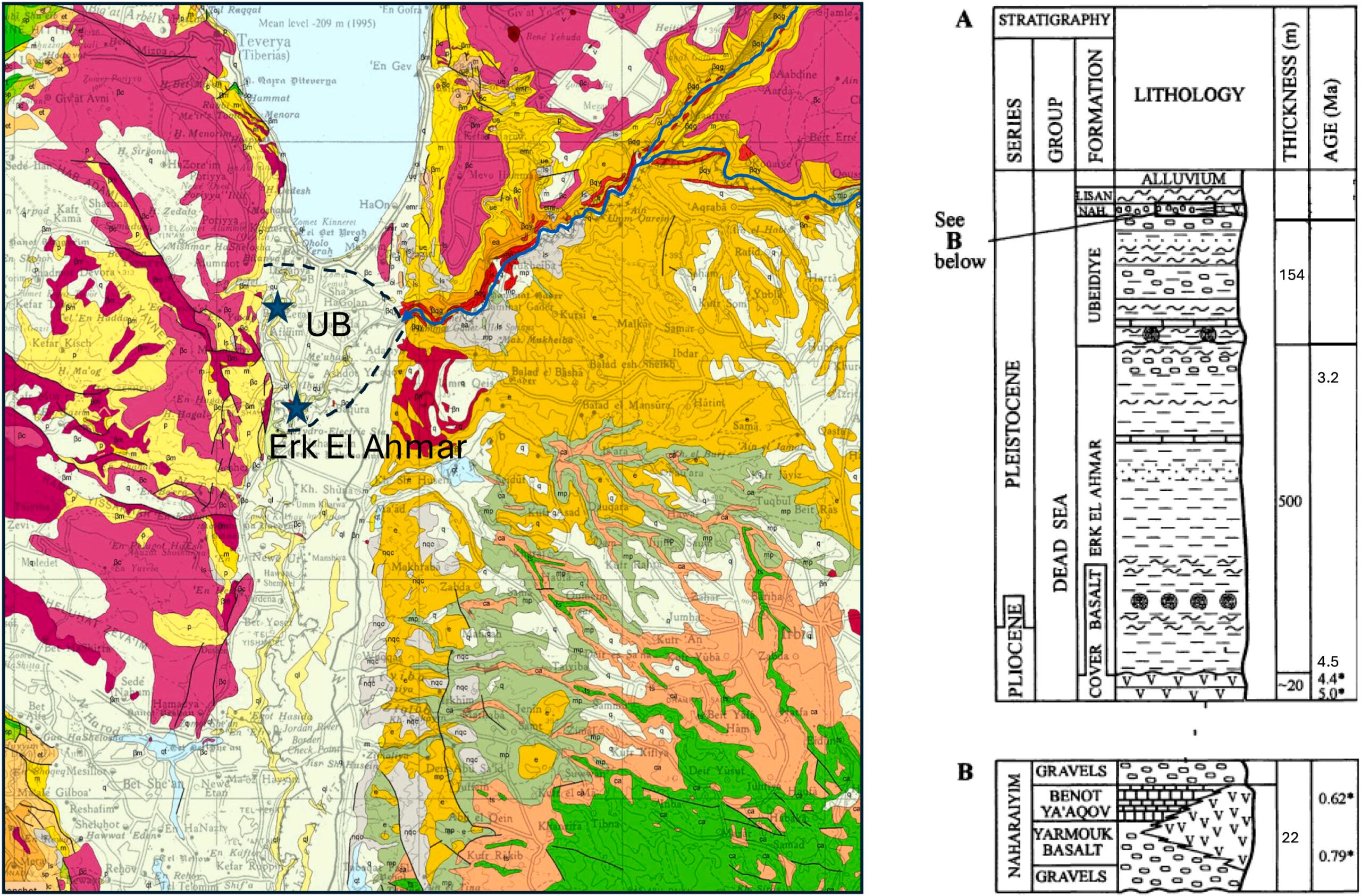

That pattern places the sequence within the Matuyama Chron, a long interval of reversed polarity dated to about 0.77 to 2.61 million years ago. The two normal samples could match either the Jaramillo subchron (0.99–1.07 million years ago) or the older Olduvai subchron (1.77–1.93 million years ago). If those two samples belong to Olduvai, unit I-26 would likely be older than 1.93 million years.

The second clock came from uranium-lead dating of fossilized Melanopsis shells, a freshwater snail preserved in the sediment. The U-Pb ages ranged from about 0.675 ± 0.037 million years to 1.3 ± 0.6 million years (2σ). The paper treats these as minimum ages because the shells went through extended cycles of dissolution and redeposition during diagenesis. Even the oldest age, the authors argue, likely sets only a floor, not the true burial age of the layer.

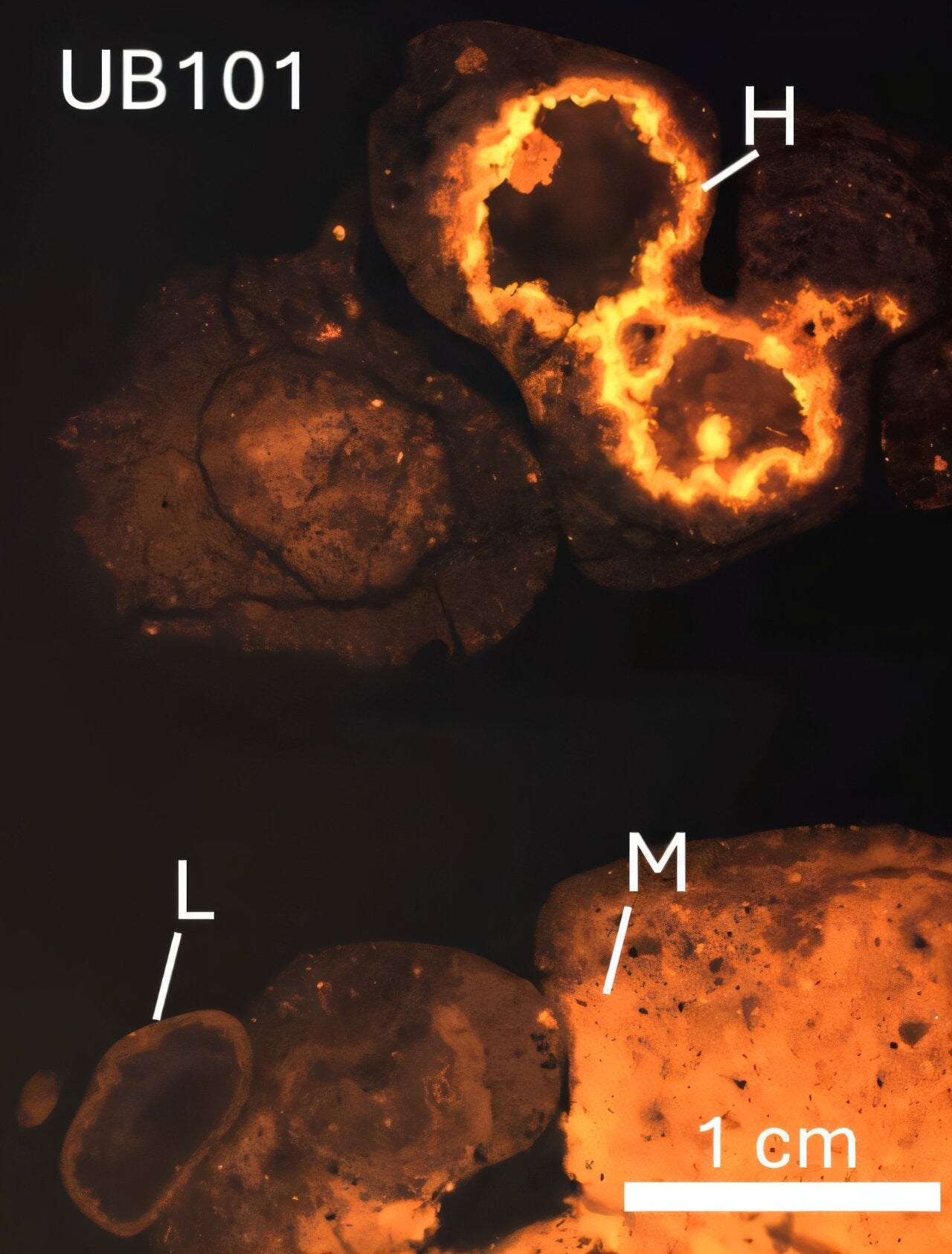

A third clock came from cosmogenic isotope burial dating of chert clasts, using the 10Be and 26Al produced when rocks sit near the surface. The team collected 10 samples from the lower, newly exposed two meters of unit I-26. One was a single chert nodule, and the other nine were amalgamated collections of about 200 small chert clasts per sample. These clasts were traced to the middle Eocene Adulam formation.

Here is where the story got messy. A simple, straightforward read of the cosmogenic isotope data produced burial ages between 2.87 ± 0.13 million years and 3.49 ± 0.13 million years, with a mean of 3.16 ± 0.46 million years.

That number clashed with several lines of evidence spelled out in the study itself: the reversed magnetic signal in unit I-26, the active tectonic setting of the Dead Sea Rift, and the archaeological record that places the earliest Acheulean in East Africa around 1.8 million years ago. The paper also notes that a past idea that ‘Ubeidiya rodents included Pliocene taxa does not hold up under more recent taxonomic reanalysis, which instead supports a 2 million-year lower limit.

So the authors did not accept the simple burial ages. They built a numerical model to account for sediment recycling, with an exposure-burial history that could generate very high 10Be concentrations alongside low 26Al/10Be ratios without requiring an implausibly long surface exposure in a rift setting.

That model produced a most probable burial age for unit I-26 of 2.69 million years, with a skewed distribution that favored older ages over younger ones. Yet when the model is restricted to periods consistent with reversed polarity, the median age drops to 2.05 million years.

The paper then narrows the realistic windows further. It lays out three possible age ranges when combining the cosmogenic modeling, the paleomagnetic constraints, the geological bounding ages of the formation, and the U-Pb minimum ages: 1.19–1.77 million years, 1.93–2.13 million years, and 2.14–2.61 million years.

The study argues the oldest window is very unlikely given the current understanding of human evolution and biochronology. That leaves two. The cosmogenic model’s skew favors the older of the remaining options, and the study highlights 1.93–2.13 million years as the most probable age range. The median age for model outcomes that fit reversed polarity, 2.05 million years, sits inside that band.

From there, the authors make a conservative headline claim: ‘Ubeidiya is at least 1.9 million years old.

This revised timeline matters because it pulls ‘Ubeidiya closer to the well-known Dmanisi site in Georgia, dated in the study to 1.85–1.78 million years ago. In that framing, early humans were present across different parts of Eurasia around the same time.

The authors also connect the age shift to a long-running question about stone tool traditions. ‘Ubeidiya’s lithic assemblage has been classified as Early Acheulean, though some researchers have described it as “Developed Oldowan,” following terminology used for Olduvai Gorge. If ‘Ubeidiya really sits at or beyond 1.9 million years, the study argues, it raises the possibility that Oldowan and Acheulean traditions coexisted in the region and dispersed around the same broad time window.

The paper is careful about what it can and cannot pin down. Uranium-lead ages on shells are treated as minimum constraints due to prolonged diagenesis. The paleomagnetic record is complicated by widespread overprinting and the fact that only a minority of samples met the quality criteria. The cosmogenic isotope results, meanwhile, required modeling because simple interpretations produced ages that contradicted other evidence.

That modeling depends on an added idea, and the study leans into it: sediment recycling within the Dead Sea Rift.

To explain the isotope puzzle, the authors focus on where the chert clasts could have come from, and how often they might have been buried, eroded, transported, and redeposited.

They point to three possible sources. One is direct transport of Eocene chert from bedrock outcrops in the southern Golan Heights and the Trans-Jordanian Mountains, carried through the Yarmuk Canyon into the Jordan Valley. Another is Miocene sediments in the Yarmuk drainage system that contain recycled Eocene chert. The third is older Pliocene sediments already deposited inside the rift itself, especially the ‘Erk el Ahmar Formation, dated in the study to 4.5–3.2 million years.

The study argues that direct bedrock transport during the early Pleistocene likely supplied only a minor fraction of the unit I-26 sediment. It instead proposes that much of the material was recycled from earlier rift deposits, such as ‘Erk el Ahmar sediments that had already acquired a cosmogenic signature: high concentrations from slow erosion early on, and low ratios from long burial.

Later tectonic deformation and erosion could have exposed and moved those older sediments short distances within the rift before redepositing them along the shoreline of paleo-lake ‘Ubeidiya.

In that view, the apparently contradictory cosmogenic ages are not a failure of the method. They are a fingerprint of a landscape that kept reworking its own deposits.

Research findings are available online in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

The original story “1.9 million-year-old finding points to the earliest evidence of humans outside of Africa” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post 1.9 million-year-old finding points to the earliest evidence of humans outside of Africa appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.