You are looking at one of the most important sensory shifts in mammal history: the rise of sensitive hearing. Modern mammals rely on a middle ear with an eardrum and tiny bones that detect faint airborne sounds. This ability gave early mammals a major advantage, especially at night, when dinosaurs dominated daylight hours.

New research from paleontologists at the University of Chicago suggests this kind of hearing began far earlier than scientists once believed. By studying a 250-million-year-old mammal ancestor, the team found evidence that advanced hearing evolved tens of millions of years before true mammals appeared.

The study focuses on Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a small, burrowing animal that lived just after Earth’s largest mass extinction. Although not a mammal, it belonged to a group that sat close to the mammalian family tree.

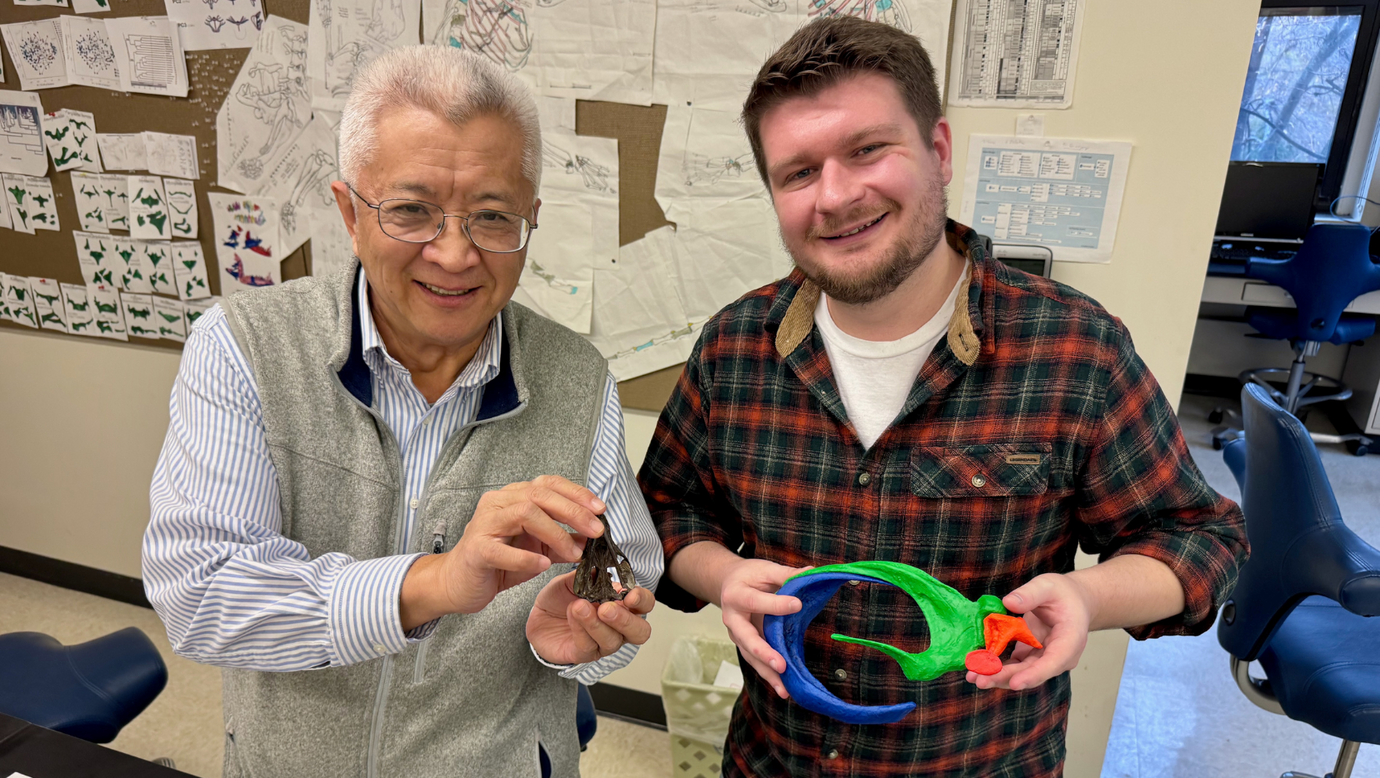

The work was led by Alec Wilken, a graduate student, alongside professors Zhe-Xi Luo and Callum Ross. Their findings were published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“For decades, scientists debated how early mammal relatives heard the world around them. Many believed these animals relied mainly on bone vibration, picking up ground movement through their jaws,” Wilken explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“That idea came from the anatomy. In early mammal ancestors, the bones that now sit in your middle ear were still attached to the jaw. Without a detached ear structure, airborne hearing seemed unlikely,” he continued.

In the 1970s, Edgar Allin, a paleontologist at the University of Illinois Chicago, proposed a different view. He suggested that some of these animals may have had a primitive eardrum stretched across part of the jaw.

At the time, the idea was intriguing but impossible to test. Fossils alone could not show how sound moved through soft tissue that no longer exists.

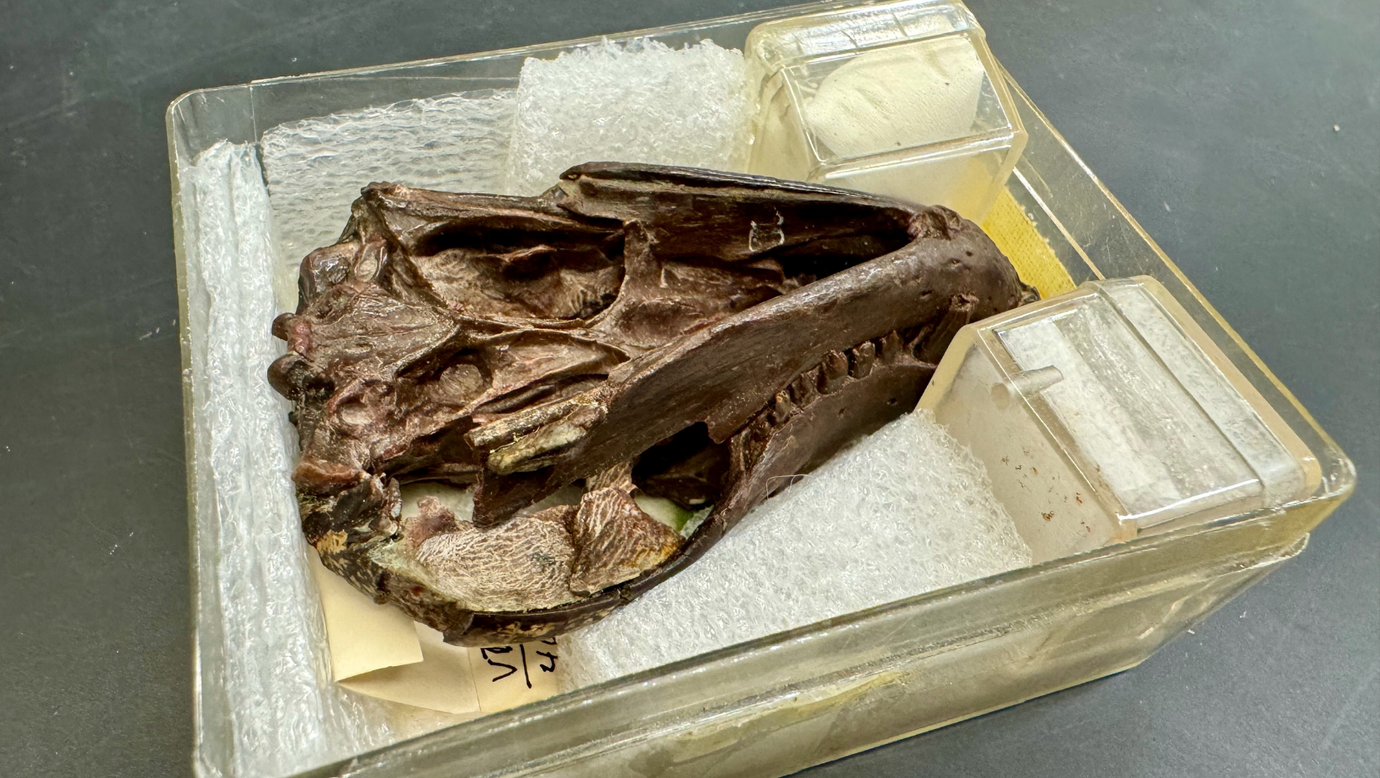

That barrier changed with modern imaging. Wilken and his colleagues worked with a well-preserved Thrinaxodon skull housed at the University of California Berkeley Museum of Paleontology.

Using high-resolution CT scanning at the University of Chicago’s PaleoCT Laboratory, they created a detailed digital model of the skull and jaw. Every curve and joint was mapped in three dimensions.

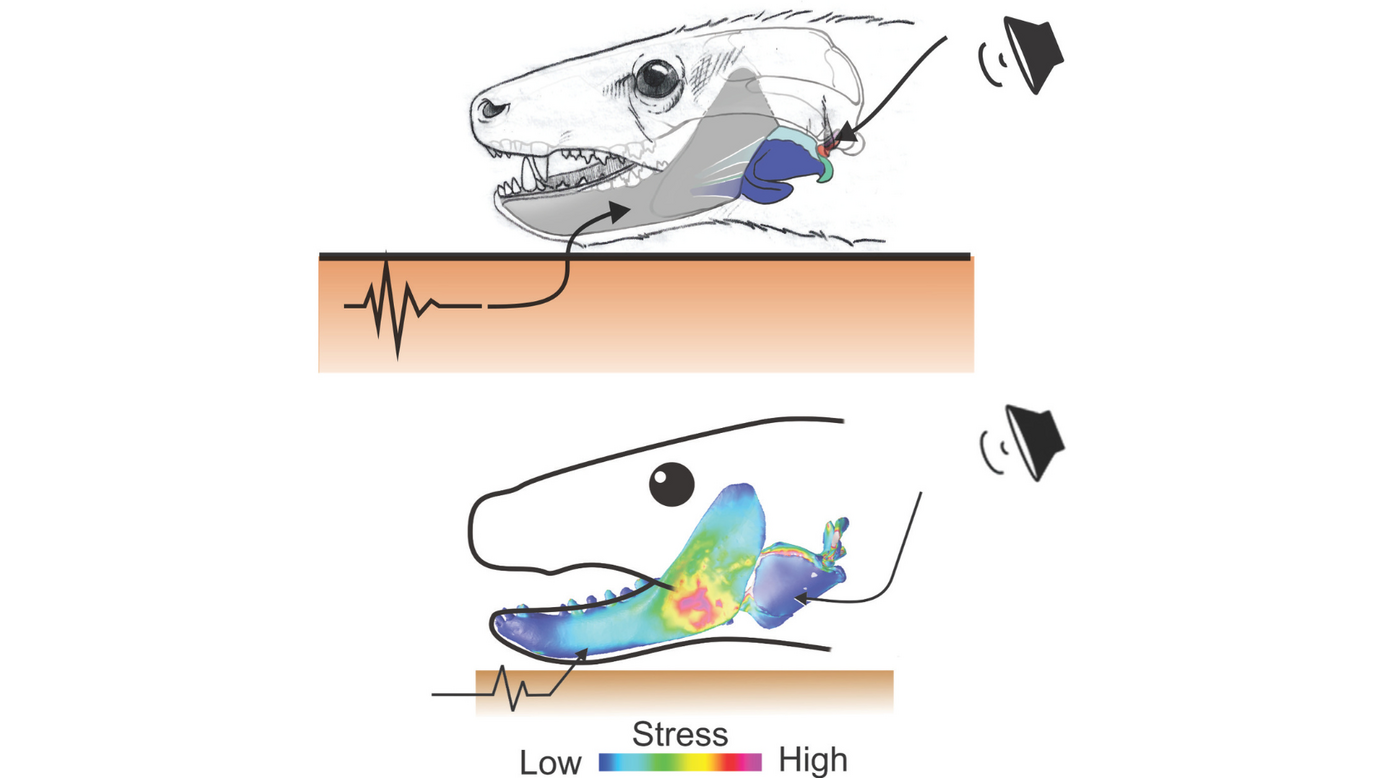

From there, the team treated the fossil like an engineering problem. They applied finite element analysis, a method engineers use to test how structures respond to stress.

The researchers assigned realistic properties to bone, cartilage, and soft tissue based on living animals. Then they simulated how sound waves would move through the jaw and ear region.

The results showed that bone-based hearing alone would have been weak. Vibrations traveling through the jaw barely reached the levels needed for hearing.

By contrast, a soft tissue membrane placed across a hooked section of the jaw performed far better. The modeled eardrum vibrated in a way that efficiently moved the tiny ear bones.

Those vibrations produced enough pressure to stimulate the auditory nerve. In practical terms, Thrinaxodon could hear airborne sound in a meaningful way.

“For almost a century, scientists have been trying to figure out how these animals could hear,” Wilken said. “Now, with our advances in computational biomechanics, we can start to say smart things about what the anatomy means for how this animal could hear.”

The findings suggest that jaw listening still played a role. However, the eardrum likely handled most hearing tasks.

This discovery pushes back the origin of tympanic hearing by nearly 50 million years. Until now, scientists thought this ability arose much later, closer to the first true mammals.

Luo explained how the digital approach made the difference. “Once we have the CT model from the fossil, we can take material properties from extant animals and make it as if our Thrinaxodon came alive,” he said.

“That hasn’t been possible before, and this software simulation showed us that vibration through sound is essentially the way this animal could hear.”

The study also helps clarify how jaw bones slowly shifted roles. Over time, these bones became fully dedicated to hearing, separating from the jaw entirely.

Sensitive hearing is one of the traits that defines mammals today. It supports communication, hunting, and social behavior.

By showing that advanced hearing appeared earlier, the research reshapes how you understand mammal origins. Many mammal traits likely evolved step by step, long before mammals themselves emerged.

Wilken said the approach allowed researchers to test a long-standing idea directly. “We took a high concept problem and tested a simple hypothesis using these sophisticated tools,” he said.

“And it turns out in Thrinaxodon, the eardrum does just fine all by itself.”

The work also highlights how new technology can unlock old fossils. Questions once thought unanswerable can now be explored in detail.

This research changes how scientists interpret the fossil record. It suggests that key mammalian traits evolved earlier and more gradually than assumed. Future studies can now apply similar modeling to other fossil species.

The findings also strengthen links between anatomy, function, and behavior. Understanding early hearing helps researchers reconstruct how ancient animals lived, hunted, and avoided danger.

Beyond paleontology, the work shows how engineering tools can advance biology. These methods may guide future studies of hearing loss, ear development, and sensory evolution.

By revealing how complex hearing systems emerged, the research deepens your understanding of how evolution solves biological challenges over time.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post 250-million-year-old mammal ancestor could hear sounds long before modern mammals evolved appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.