The earliest hominins in Europe shared their environment with large mammals and elephants were some of the largest animals ever to exist on Earth. Elephants weighed around ten thousand kilograms (33,070 pounds) and stretched fifteen feet (five meters) from the ground to the tip of their tusks. The presence of large mammals and other forms of life greatly affected the lifestyle of early humans, influencing their ability to hunt and collect meat, travel, and create tools from mammoth and elephant bones, as well as from the bones of other animals.”

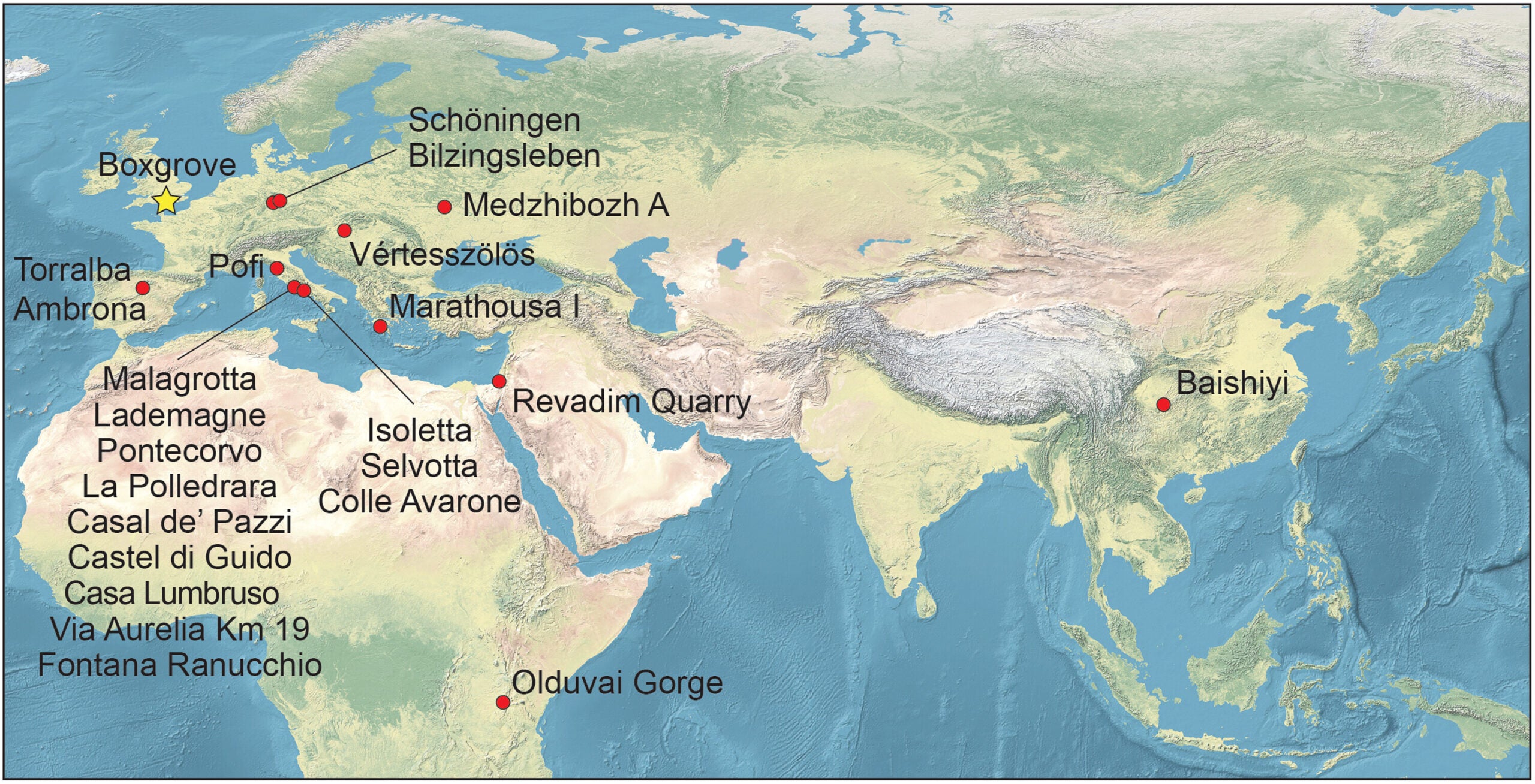

A recent article by researchers from University College London and the Natural History Museum indicates that the earliest hominins in Europe were not simply scavenging and butchering these large mammals, but were deliberately creating tools from the bones of these animals. The research, which was published in the journal Science Advances, comes from the Boxgrove site in southern England, approximately 480,000 years ago. This represents the oldest known use of elephant bone tools in Europe.

This discovery supports the notion that early hominins utilized elephant bones for more than just food. They were used as tools in the process of creating stone tools through the use of soft bones, specifically in the process of producing sharpened flint tools. This work was conducted by Simon Parfitt of UCL, along with a team of researchers based in Britain.

Elephants were both a source of food and a danger to hominins living in Europe. A single elephant carcass could provide thousands of kilograms of usable meat, fat, marrow, and skin, as well as a large amount of bone material for use in tool production. In addition to their immediate use as food, many hominins returned to use the remains of elephants as raw materials for tool-making long after the elephant was dead.

Most Paleolithic sites throughout Europe contain significant evidence of elephant remains, supporting the conclusion that these large mammoths were extremely important to both the diets and economies of early hominins. It is also clear that early hominins returned to utilize elephant bones over and over again, indicating that early hominins utilized elephant bones for more than simply being thrown away as waste. Marrow and grease contributed significant calories to sustenance. Many thick bones could be burned for fuel.

Over a number of years, ivory and bone could be made into shelter and tools, as well as decorative or artistic items for later use. Thousands of years ago, elephants provided many species of animals and people with the means to survive.

In Africa, as early as 1.5 million years ago, evidence of tools made from elephant bone was discovered at Olduvai Gorge and other locations. However, there is little to no evidence of similar tools in Europe, and the authenticity of such finds is often debated and disputed. While it has proven difficult to establish unambiguous Lower Paleolithic evidence, recent findings have proven otherwise.

The archaeological site designated as Boxgrove lies on the southern side of Chichester Harbour in West Sussex, England. It existed approximately half a million years ago along a shore on an ancient river with cliffs that were primarily composed of chalk. As time passed, the river was replaced by ponds and springs of fresh water. These transitions preserved a detailed record of scenarios in which many humans created and utilized tools.

Excavations carried out over the past several decades have produced thousands of stone tools, as well as butchered animal bones and rare hominin fossils, including the lower part of the leg bone tibia (long bone in lower leg) and teeth. The site is most well-known for the large number of expertly made handaxes discovered at or near the same location. This includes those situated at water sources where large animals congregated.

The Waterhole Site has yielded over 450 finished and unfinished handaxes, indicating a high degree of skill and training among the artisans who produced the handaxes. Their high degree of consistency demonstrates that many of the same techniques used by the artisans contributed to the production of the handaxes.

A scientific analysis of wear patterns on Boxgrove handaxes indicated that handaxes were used primarily for cutting meat, with little potential for use in digging or woodworking. Stone tool makers who produced symmetrically shaped tools created their products by switching between hard stone hammers and softer hammers made from bone or antler.

The use of soft hammers allowed tool makers to have more control when crafting their products. The use of soft hammers allowed the removal of smaller flakes, which made it easier to fine-tune sharp edges. In addition to allowing for more control in the crafting of tools, soft hammers are also much more common than hard stone hammers at Boxgrove.

The predominance of soft hammers at Boxgrove indicates that, at that site, these tools were made using advanced techniques of stone working. Of the various tools found at Boxgrove, one tool stood out among the rest.

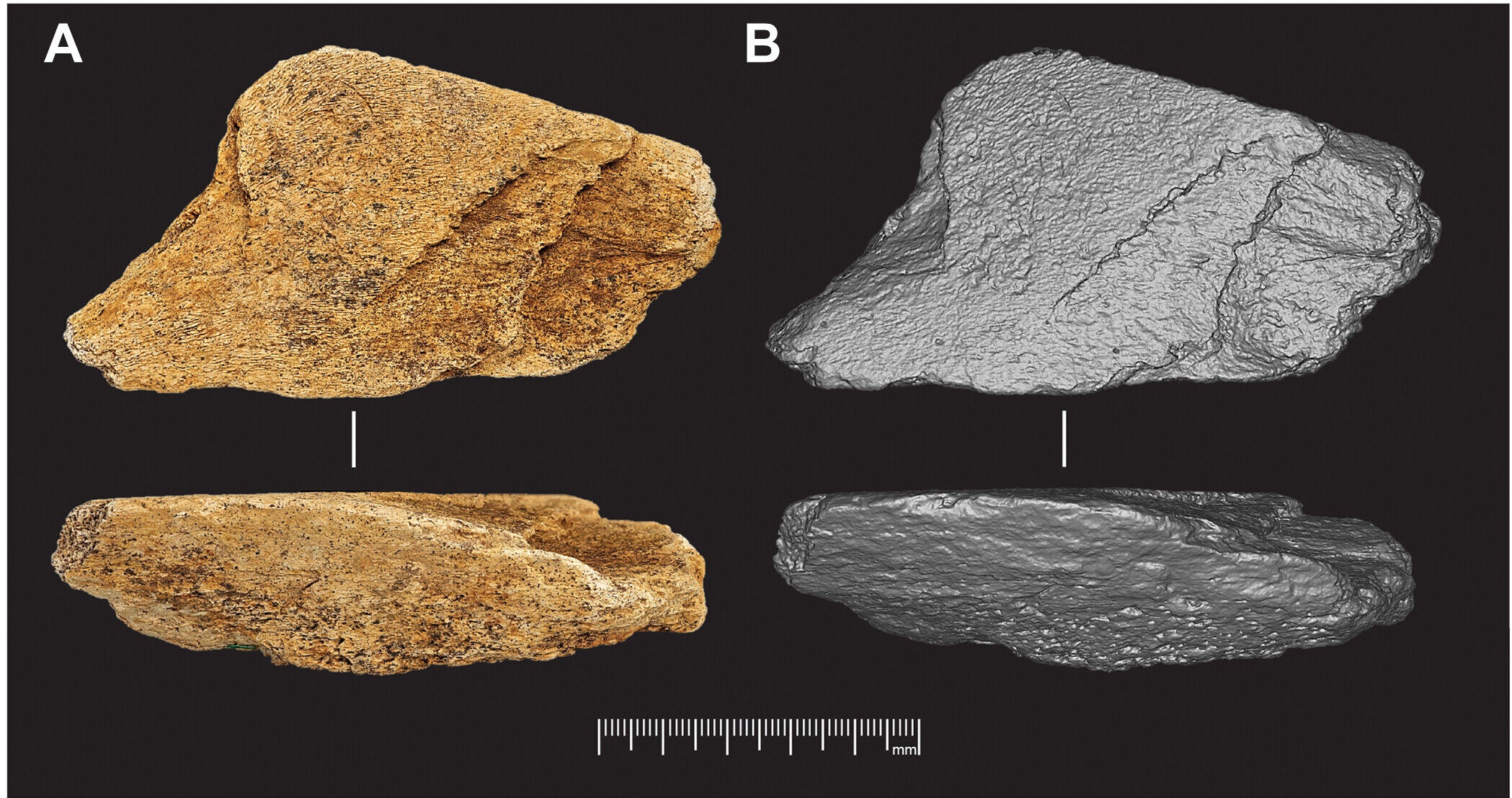

Upon reanalysis, the newly classified elephant bone retoucher was recovered from sediments at the Waterhole Site, located in the intertidal zone. Although this object was originally discovered in the early 1990s, it was only after conducting detailed reanalyzes that it was classified as a tool.

This tool is a triangular fragment of thick cortical bone measuring approximately 11 centimetres long, 6 centimetres wide, and 3 centimetres thick. The outer cortex of the bone is very dense, indicating that this fragment came from an elephant or mammoth. However, the fragment is too small to enable species to be identified.

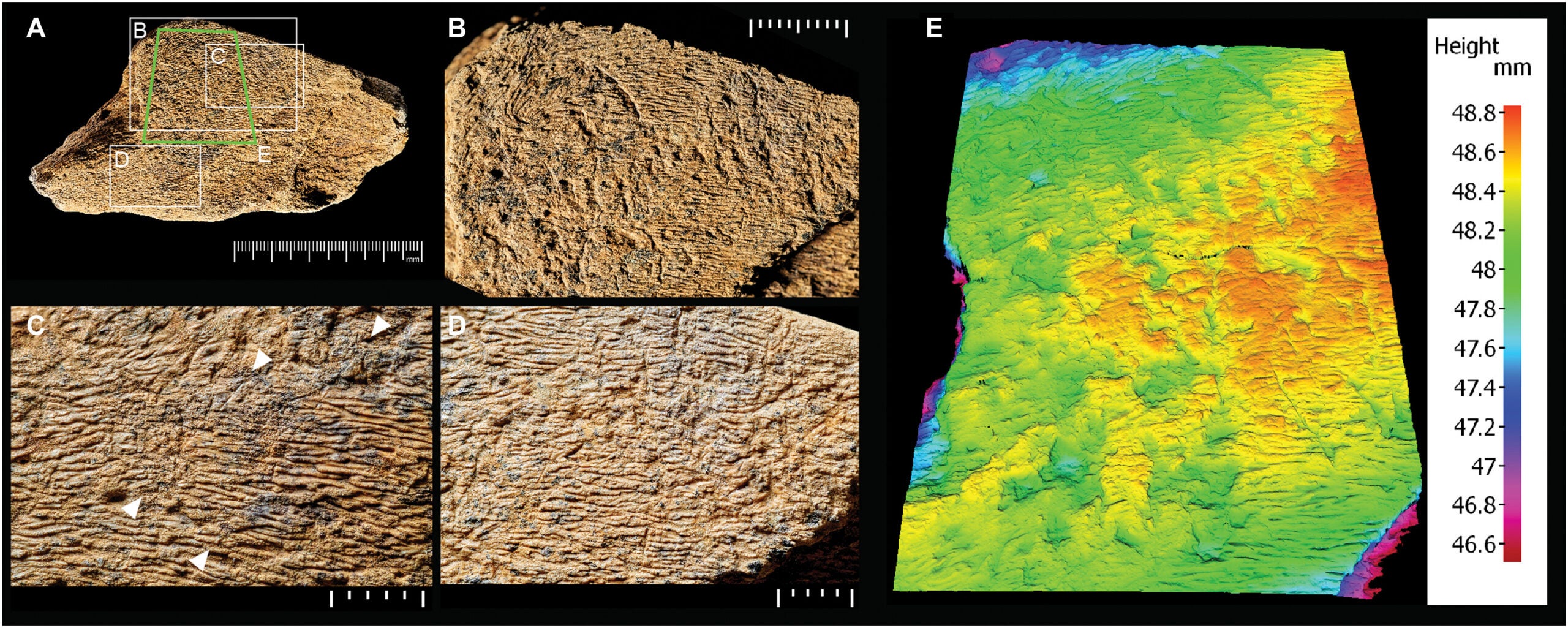

Through the use of modern technology such as 3D scanners and electron microscopes, scientists have determined that there were two distinct stages of modification to the retoucher. The retoucher was broken when the bone was still green, still about 1.5 years from being mature. This created a blank that was more manageable.

After breaking the bone, flakes were methodically removed and retouched at both ends. The fracture patterns observed are consistent with controlled retouching, rather than random breakage or marrow extraction.

Careful cut marks on the surface indicate that soft tissue was removed using stone tools before the tool was finished. Other bone tools from Boxgrove exhibit the same types of cut marks, indicating that bone working at Boxgrove was accomplished through controlled, planned stages.

The evidence for the use of this tool can be determined by the wear caused by use. There are three different areas of the surface of the bone that show pronounced clusters of pits, grooves, and scratches. These are the same type as those found on known retouchers.

These tools were extended through contact. That is, a tool was made to reach a certain height through repeated contact.

In addition to the above, small pieces of flint are present in many of these grooves. The analysis of these pieces of flint has shown that they were sourced from local sources. Additionally, the direction and shape of these markings indicate the consistent angle at which the handaxes were struck. Therefore, the marks indicate that the marks were made from striking the tool with controlled force repeatedly.

Given the depth of the grooves, it can be concluded that these were light strikes instead of heavy strikes. Therefore, they were junior repairs of butchering.

Elephant bones are extremely rare at Boxgrove. Only about twenty different pieces have been discovered from the entire site. This indicates that the tool made from the bone likely was cut from a different location. Therefore, the bones of this animal may have died from natural causes or may have been scavenged, and the usable pieces were retained after they were scavenged.

There were no flakes found at the Waterhole Site from the initial shaping of the bone tool. Therefore, this tool was made at a different location and brought there. This supports the conclusion that some tools were curated and transported over the landscape.

Simon Parfitt, the lead author, states, “This remarkable find shows how ingenious and resourceful our ancient ancestors were. They not only knew what materials to use but also demonstrated a high level of sophistication in their knowledge of crafting high-quality stone tools. Having a rare but highly useful resource, we would assume that this was a valuable tool.”

“The discovery of the elephant bone fragment shows a level of cognitive complexity in our ancient ancestors,” Dr. Silvia Bello, a merit researcher at the Natural History Museum, told The Brighter Side of News. “They were advanced in their use of tools. Therefore, collecting and creating the shape of an elephant bone fragment, then using it over and over to shape and sharpen stone tools, demonstrates a significant level of complex and abstract thought. Our ancient ancestors were resourceful gatherers of all materials available to them and were knowledgeable regarding the best way to use them.”

This find demonstrates that a change occurred within the Acheulean tradition. Earlier handaxes were thicker and made primarily with hard hammers and initial designs, while later examples, such as those discovered at Boxgrove, were made with soft hammers and carefully planned.

By the time period of approximately 500,000 B.C.E., humans were identified to be producers of tools and maintainer. Thus, they were preparing to continue to make and maintain equipment over time.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post 500,000-year-old elephant bone tool reveals advanced planning and skill in early human ancestors appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.