A set of ancient human fossils found on Morocco’s Atlantic coast now sits on one of the tightest timelines in African prehistory. The remains come from Thomas Quarry I, and a new analysis pins them to about 773,000 years ago, give or take 4,000 years. That level of precision is rare for fossils this old, and it pulls you closer to a moment near the split that later led to modern humans, Neandertals, and Denisovans.

The research is led by an international team including Jean-Jacques Hublin of Collège de France and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, David Lefèvre of Université de Montpellier Paul Valéry, Giovanni Muttoni of Università degli Studi di Milano, and Abderrahim Mohib of Morocco’s Institut National des Sciences de l’Archéologie et du Patrimoine, known as INSAP. The team describes new hominin fossils that show a mix of older and more modern features, and they place them in a geological record that is unusually clear.

For anyone trying to picture the human family tree, the hardest part often is timing. Fossils can be stunning, but their age can be blurry. Here, the timeline is the headline. A high-resolution magnetic record captured a major flip in Earth’s magnetic field, and the fossils sit right in that transition.

The discoveries build on more than three decades of fieldwork under the Moroccan-French program “Préhistoire de Casablanca.” You can feel the patience behind that kind of effort. The team did long excavations, careful layer-by-layer mapping, and large geological studies across the southwest part of the city.

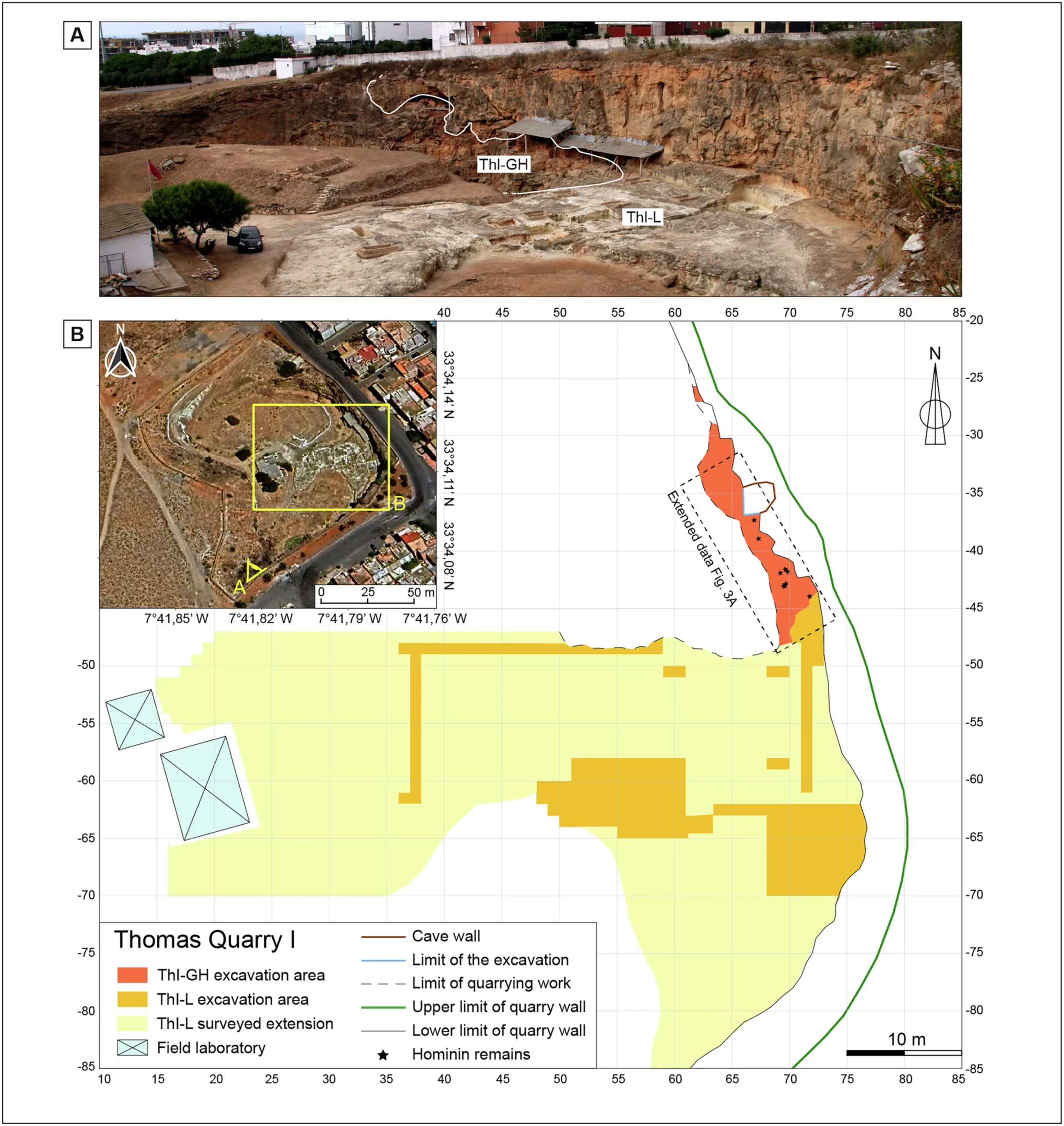

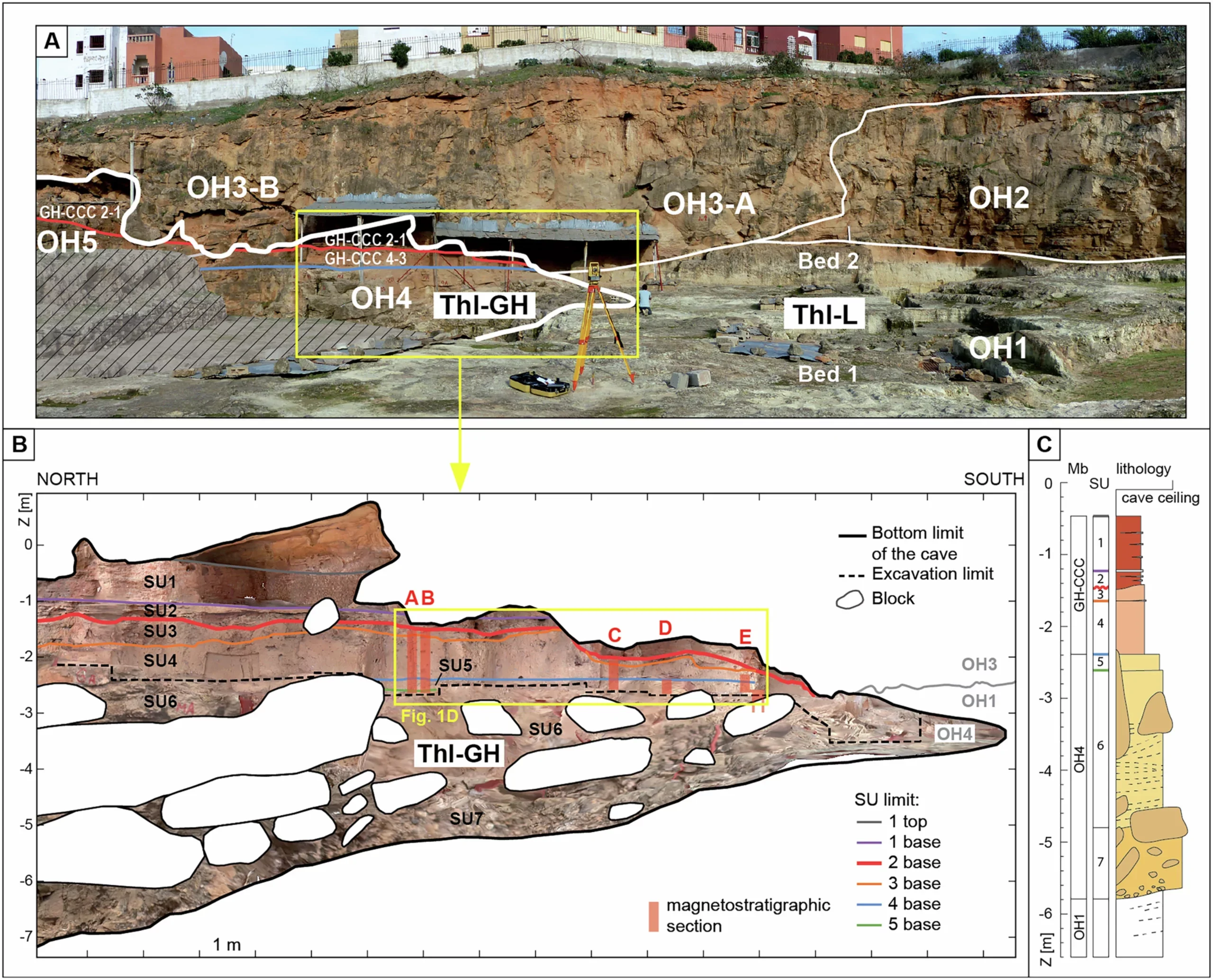

That slow work revealed an unusual cave sequence inside Thomas Quarry I, in an area known as the “Grotte à Hominidés.” The setting matters because the fossils did not come from a loose or mixed layer. They came from sediments that stayed in order.

Mohib framed the result as a product of collaboration, not luck. “The success of this long-term research reflects a strong institutional collaboration involving the Ministère de la Jeunesse, de la Culture et de la Communication Département de la Culture of the Kingdom of Morocco (through INSAP) and the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères of France (through the French Archaeological Mission Casablanca)”.

Support also came from institutions in Italy, Germany, and France, including the Università degli Studi di Milano and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. That network helped turn a local cave deposit into a global point of reference.

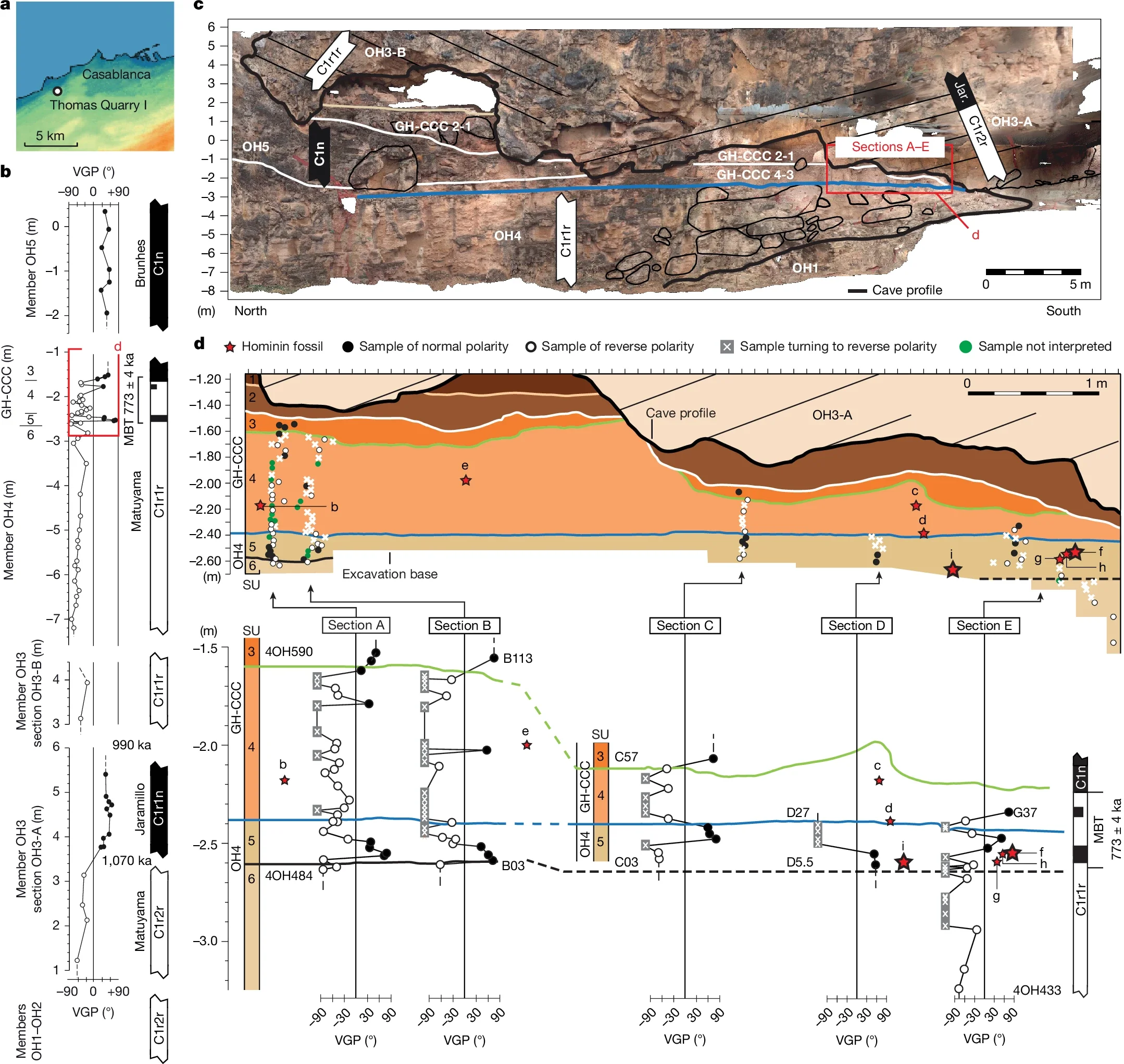

Thomas Quarry I sits within raised coastal formations along the Rabat–Casablanca littoral. Over long periods, sea levels rose and fell, winds built dunes, and coastal sands hardened quickly. Those shifts created caves and preserved what later filled them.

Jean-Paul Raynal, a co-director of the program during the excavation that uncovered the fossils, emphasized why the coast matters. He said the region is known for “its exceptional succession of Plio-Pleistocene palaeoshorelines, coastal dunes and cave systems.” He also noted that repeated sea-level swings and rapid cementation created “ideal conditions for fossil and archaeological preservation”.

That bigger landscape holds an unusually deep record of life and toolmaking. The wider Casablanca region documents early Acheulean stone tools and later developments, along with animal fossils that reflect changing environments.

Thomas Quarry I itself is known for very old Acheulean industries in northwest Africa, dated to about 1.3 million years ago. The site also sits near Sidi Abderrahmane, a classic reference point for Middle Pleistocene prehistory in the region.

Within that broader context, Lefèvre described the “Grotte à Hominidés” as a cave system carved by a marine highstand and later filled with sediments that kept the fossils in a secure and undisturbed layer sequence.

The dating method behind this work is magnetostratigraphy, a tool that reads changes in Earth’s magnetic field recorded in sediments. Over geological time, the magnetic field flips. North becomes south, and the polarity reverses. Those flips leave a sharp signal in layers of rock and sediment, and that signal matches worldwide.

The key marker here is the Matuyama–Brunhes transition, the last major geomagnetic polarity reversal. It occurred around 773,000 years ago. Because it is global and abrupt on geological timescales, it acts like a precise timestamp.

At the “Grotte à Hominidés,” rapid sediment buildup allowed the team to capture the transition in fine detail. Serena Perini explained why that matters. “Seeing the Matuyama–Brunhes transition recorded with such resolution in the ThI-GH deposits allows us to anchor the presence of these hominins within an exceptionally precise chronological framework for the African Pleistocene.”

The team collected 180 magnetostratigraphic samples, an unusually high number for a hominin site of this age. Those samples captured the end of the Matuyama Chron, the transition itself, and the start of the Brunhes Chron. The researchers even estimate the transition’s short duration at 8,000 to 11,000 years. The hominin-bearing sediments formed during that window, which strengthens the age estimate.

The team also notes that animal evidence supports the same time frame, but they treat the magnetic record as the key anchor.

The fossil assemblage appears to come from a carnivore den. The researchers point to a hominin femur that shows clear signs of gnawing and consumption. The collection includes a nearly complete adult mandible, a second adult half mandible, a child mandible, several vertebrae, and isolated teeth.

When you picture these finds, it helps to hold two ideas at once. First, these were living beings in a risky landscape. Second, their bones now sit in a rare time-locked deposit.

The anatomy adds another layer of tension. The jaws and teeth show a mosaic of traits, with features that look archaic and others that look more derived. Some traits recall hominins from Gran Dolina at Atapuerca, which are often grouped under the label Homo antecessor. The paper suggests that ancient population contacts between northwest Africa and southern Europe may have existed earlier. By the time of the Matuyama–Brunhes transition, the groups look clearly separated.

The team used micro-CT imaging, geometric shape analysis, and comparative anatomy. Matthew Skinner focused on a hidden feature inside teeth, the enamel-dentine junction, which can stay intact even when enamel is worn. “Using microCT imaging we were able to study a hidden internal structure of the teeth, referred to as the enamel-dentine junction, which is known to be taxonomically informative and which is preserved in teeth where the enamel surface is worn away. Analysis of this structure consistently shows the Grotte à Hominidés hominins to be distinct from both Homo erectus and Homo antecessor, identifying them as representative of populations that could be basal to Homo sapiens and archaic Eurasian lineages.”

Shara Bailey described how the teeth differ from later Neandertal patterns. “In their shapes and non-metric traits, the teeth from Grotte à Hominidés retain many primitive features and lack the traits that are characteristic of Neandertals. In this sense, they differ from Homo antecessor, which, in some features, are beginning to resemble Neandertals. The dental morphological analyses indicate that regional differences in human populations may have been already present by the end of the Early Pleistocene”.

The study also pushes back on the idea of the Sahara as a permanent wall. Denis Geraads said, “The idea that the Sahara was a permanent biogeographic barrier does not hold for this period. The paleontological evidence shows repeated connections between Northwest Africa and the savannas of the East and South.”

The fossils are almost the same age as the Gran Dolina hominins, and they are older than later Middle Pleistocene fossils tied to Neandertals and Denisovans. They are also far older than the earliest Homo sapiens remains at Jebel Irhoud, by roughly 500,000 years, according to the researchers.

Genetic evidence places the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens, Neandertals, and Denisovans between about 765,000 and 550,000 years ago. The Moroccan fossils align best with the older part of that range, based on their age and their blend of traits.

Hublin summed up the stakes. “The fossils from the Grotte à Hominidés may be the best candidates we currently have for African populations lying near the root of this shared ancestry, thus reinforcing the view of a deep African origin for our species.“

This work gives researchers one of the most precisely dated African Pleistocene hominin assemblages, anchored to 773,000 years ago, plus or minus 4,000 years.

The high-resolution magnetic record and 180 samples provide a model for dating other early sites, especially where fossil ages remain uncertain.

The fossils offer new anatomical evidence for African populations near the split that later produced Homo sapiens, Neandertals, and Denisovans.

The findings strengthen the role of northwest Africa in early Homo evolution and support the idea of repeated connections across regions that include the Sahara.

The study’s tooth imaging approach, including enamel-dentine junction analysis, can help identify populations even when tooth surfaces are worn.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

The original story “773,000-year-old Moroccan cave fossils reveal human and neandertal evolutionary split” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post 773,000-year-old Moroccan cave fossils reveal human and neandertal evolutionary split appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.