A quiet region at the eastern Antarctic Peninsula carries a narrative that can seem unnervingly personal if you have witnessed something in your life collapse faster than you were prepared for.

In early 2024, researcher Naomi Ochwat, from the University of Colorado Boulder, flew above a fjord she had only seen via satellite screens. She expected to find mountain walls she recognized supporting a small glacier. Instead, she locked eyes with an open space. The ice that filled that valley had disappeared. Later, as if to articulate how shocked she was, she said simply, “I couldn’t believe the size of the area that had collapsed.”

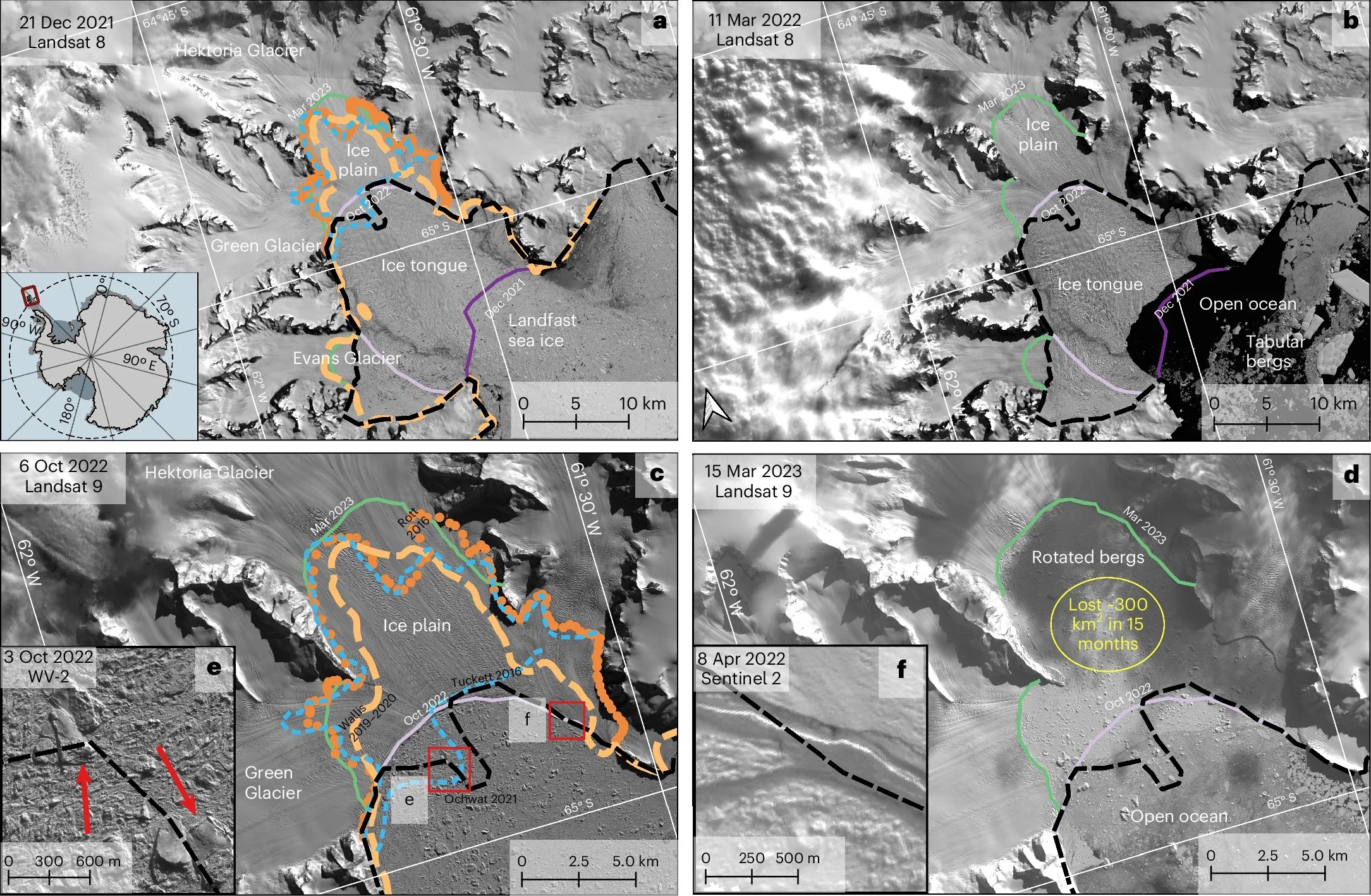

That glacier is called Hektoria. It showed signs of distress. Still, nothing hinted at what would unfold between late 2022 and early 2023. Its retreat was farther and faster than any grounded glacier in the modern record. You might envision a glacier retreating the way shorelines erode, slow and steady. But in this case, nearly half of the glacier disappeared in two months. What normally takes decades happened in weeks.

Hektoria is not one of Antarctica’s large glaciers. It covers about 115 square miles, approximately the area of Philadelphia, but the ice was important because of what it was hiding. Hektoria ice rests on an “ice plain,” which is a flat bed of rock and sediment under sea level.

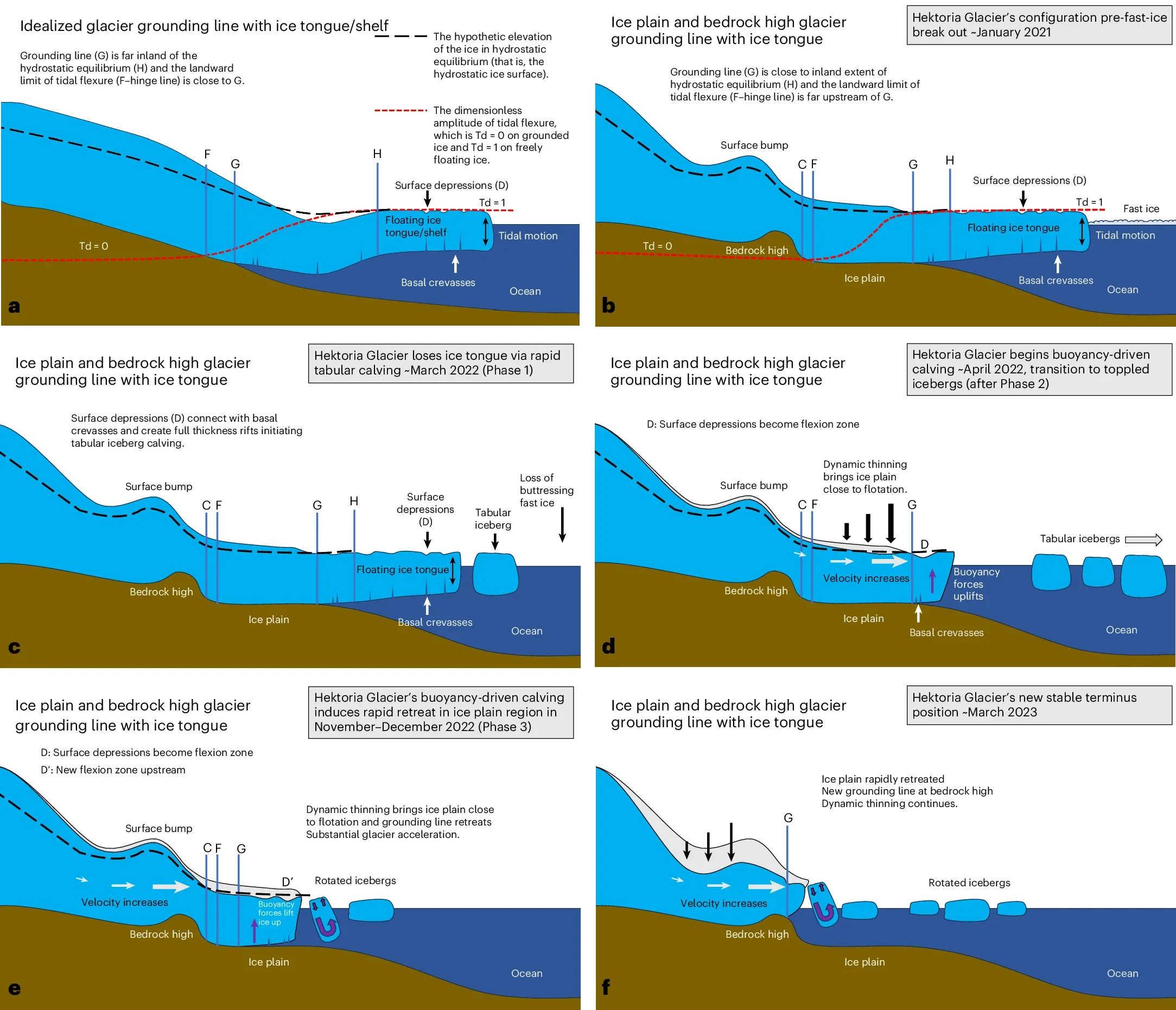

This is the configuration that makes it so vulnerable. When a glacier is situated on a deep ridge or a mountaintop, that contact helps to stabilize it. On a flat plain, however, the ice adheres to the surface more loosely. When it gets even slightly thinner, it will float. That transition will initiate a strong and rare form of breakage called buoyancy-driven calving.

You might assume that rising air temperatures or warm seawater had initiated the collapse. These driving forces are typically responsible for glacier retreat, but a new study, published in Nature Geoscience, finds the main driving mechanism is structural.

A significant contributing factor to the structure of the glacier retreat was the loss of long-standing sea ice in the nearby bay. This protective layer, known as fast ice, had long stabilized the glacier. With the fast ice gone, the glacier was elevated in height at the same time it was thinning. What followed was a domino effect.

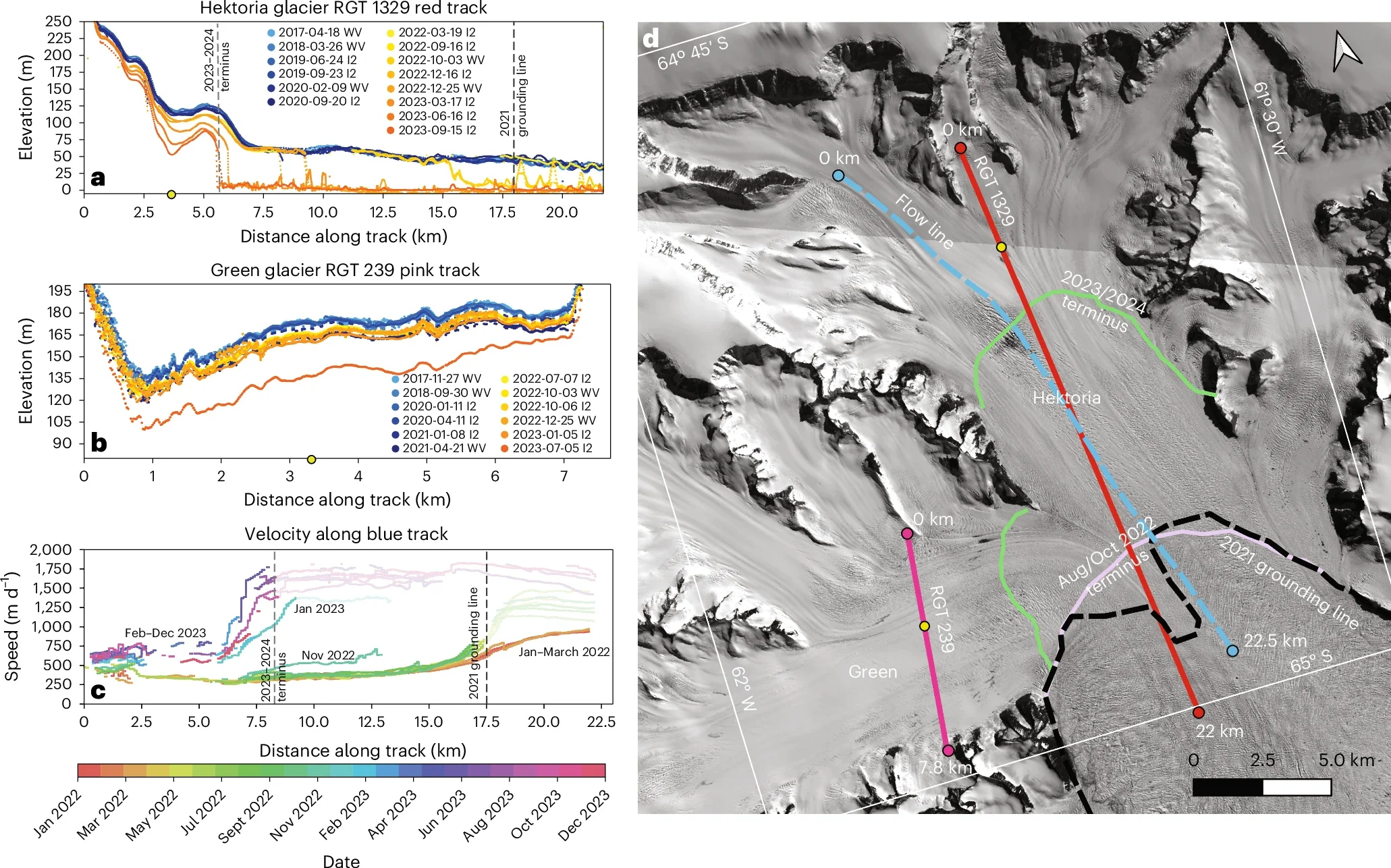

Satellite images indicated that the Hektoria glacier experienced a significant change in dynamics. Flow speeds increased approximately six times faster than previously observed. Thinning rates increased fortyfold. Then, sometime in November 2022, the glacier lifted enough off the seafloor to be able to float.

As soon as it floated, it cracked from the bottom. Forces from the ocean began to propagate crevasses upward that met fractures from the surface of the ice. These fractures created structural weaknesses that eventually created a complete break. In two months after the initial break, approximately 8.2 kilometers of the ice had fallen away. By March 2023, the total retreat had measured approximately 25 kilometers.

Ochwat and colleagues have assembled a timeline with surprising detail using data from several satellites. Instead of gathering an individual snapshot every few months, they synthesized overlapping images from different instruments, creating a more dynamic picture of the glacier’s collapse. “If we had a single image every three months, we might not be able to tell you that it lost two and a half kilometers in two days,” she said.

Seismic instruments also detected glacial earthquakes during the glacier’s retreat. These earthquakes occur when large blocks of ice suddenly shift against the rock below. The signals from the earthquakes confirmed that when Hektoria began collapsing, it was grounded on bedrock. This is significant because ice that calves while grounded contributes directly to sea level rise, whereas floating ice does not.

The collapse of Hektoria is reminiscent of patterns of glacial motion observed thousands of years ago. Research on ancient ice sheets has shown that glaciers resting on ice plains retreated hundreds of meters per day during periods of past warming. Patterns like these helped the researcher understand why Hektoria failed so rapidly, and they also raise questions about the future given that many glaciers in Antarctica are situated on similar plains.

Tidewater glaciers, which extend into the ocean, face many risks already. They flow across the seabed, shaped by deep canyons, small ridges, or broad flat zones. The shape of the bed determines the difficulty for a glacier to detach. In Hektoria’s case, there appeared to be multiple grounding lines. These are points where the glacier transitions from resting on the bedrock to floating. More than one line often identifies a topography that can lead to unstable behavior.

Senior scientist Ted Scambos, from CIRES, who collaborated with Ochwat, said that the sudden retreat alters what researchers had thought possible. “If the same conditions are set up in some of the other areas, it could accelerate sea level rise from the continent significantly,” he said.

You are not alone if you have never heard of Hektoria Glacier until now. Most people tend to ignore little glaciers that are packed away in isolated fjords. However, what might have occurred there does not remain within the Antarctic Peninsula.

Sea level rise does not occur evenly. It affects shorelines, groundwater, and storm impacts, which are connected everywhere. If even a modest glacier can collapse this rapidly, it does inspire reconsideration in scientists concerning what areas of Antarctica are vulnerable.

The study challenges people’s simple expectations, also. It undermines the notion that grounded glaciers are inherently stable glaciers. Grounded as it was, Hektoria was not grounded securely. Once thinning reached a threshold, buoyancy worked its way into the masses.

Critical discovery shows why bed design is equally relevant to climate, weather, and ocean temperature. Warming still matters and continues to contribute to raising global sea levels, but vulnerable shapes can create conditions for a sudden threshold change.

With a story like this, emotional heft for many coastal communities comes from being aware that rapid change does not limit itself to a minor glacier. Much larger glaciers with ice plain features might behave the same way should conditions work out together. The rapid retreat at Hektoria allows a warning over and above the scientific data to be heard, and invites you to consider the human, climate feedback loop effects of losing much larger bodies of ice.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Hektoria glacier’s record breaking collapse signals a much bigger Antarctic threat appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.