For years, you have probably heard that the safest move for your heart is to cut red meat as much as possible. A new study from Penn State does not throw that advice out, but it does add nuance. The research suggests that modest amounts of lean, unprocessed beef can fit into a heart friendly Mediterranean style eating pattern without raising one emerging marker of cardiovascular risk.

The marker is trimethylamine N-oxide, or TMAO. Your gut microbes help produce it when you eat animal foods such as meat and eggs. Higher blood levels of TMAO have been linked in observational studies to a greater chance of heart disease.

“Observational evidence shows higher levels of TMAO are associated with higher cardiovascular risk,” says Kristina Petersen, associate professor of nutritional sciences and senior author of the new paper. “In this study we wanted to better understand the relationship between lean beef consumption and TMAO levels in the context of a healthy, Mediterranean style diet.”

To answer that question, Petersen and an interdisciplinary team went back to data from a tightly controlled feeding trial. Thirty relatively young, healthy adults took part. For four separate four week stretches, each person ate a different menu designed by the researchers. Every meal and snack came from the study kitchen, so the team knew exactly what participants ate.

If you had joined this trial, you would have cycled through four patterns in random order, with at least a week off between them. One phase used a typical U.S. style menu, based on national data from when the study was designed. That plan provided about 52 percent of calories from carbohydrates, 15 percent from protein, and 33 percent from fat. It also included 2.5 ounces a day of regular ground or chopped beef that contained more than 10 percent fat.

The other three phases followed a Mediterranean style pattern. Those menus shifted the balance to about 42 percent of calories from carbs, 17 percent from protein, and 41 percent from fat, with more olive oil, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains than the American plan.

The difference between these three phases was how much red meat they contained: about 0.5 ounce, 2.5 ounces, or 5.5 ounces of unprocessed, lean or extra lean beef per day. All of the red meat in these phases contained 10 percent fat or less, and some cuts had under 5 percent fat.

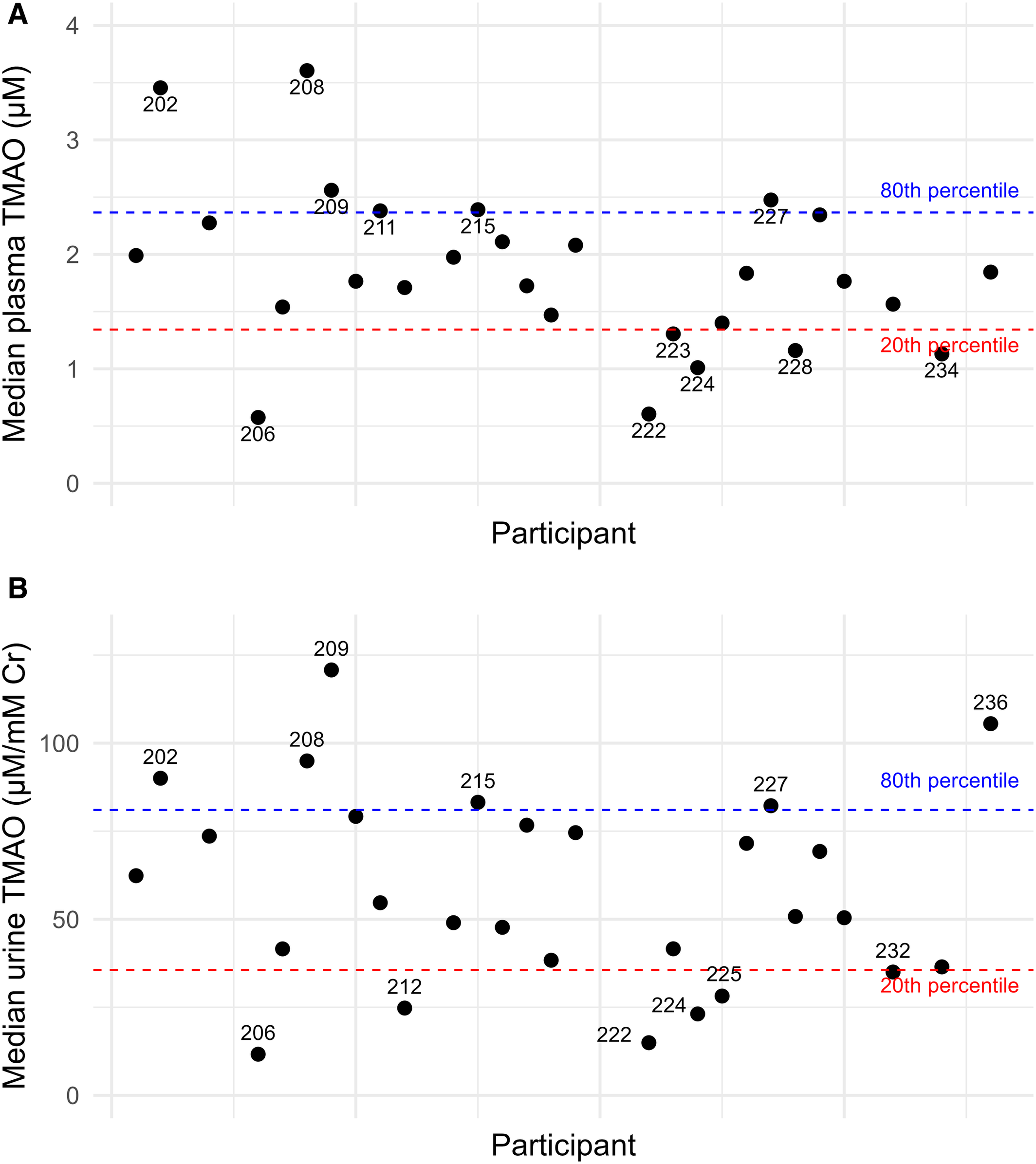

Throughout the study, the team collected blood, urine, and stool samples. They measured TMAO in multiple ways and also profiled the diversity of gut microbes in each person.

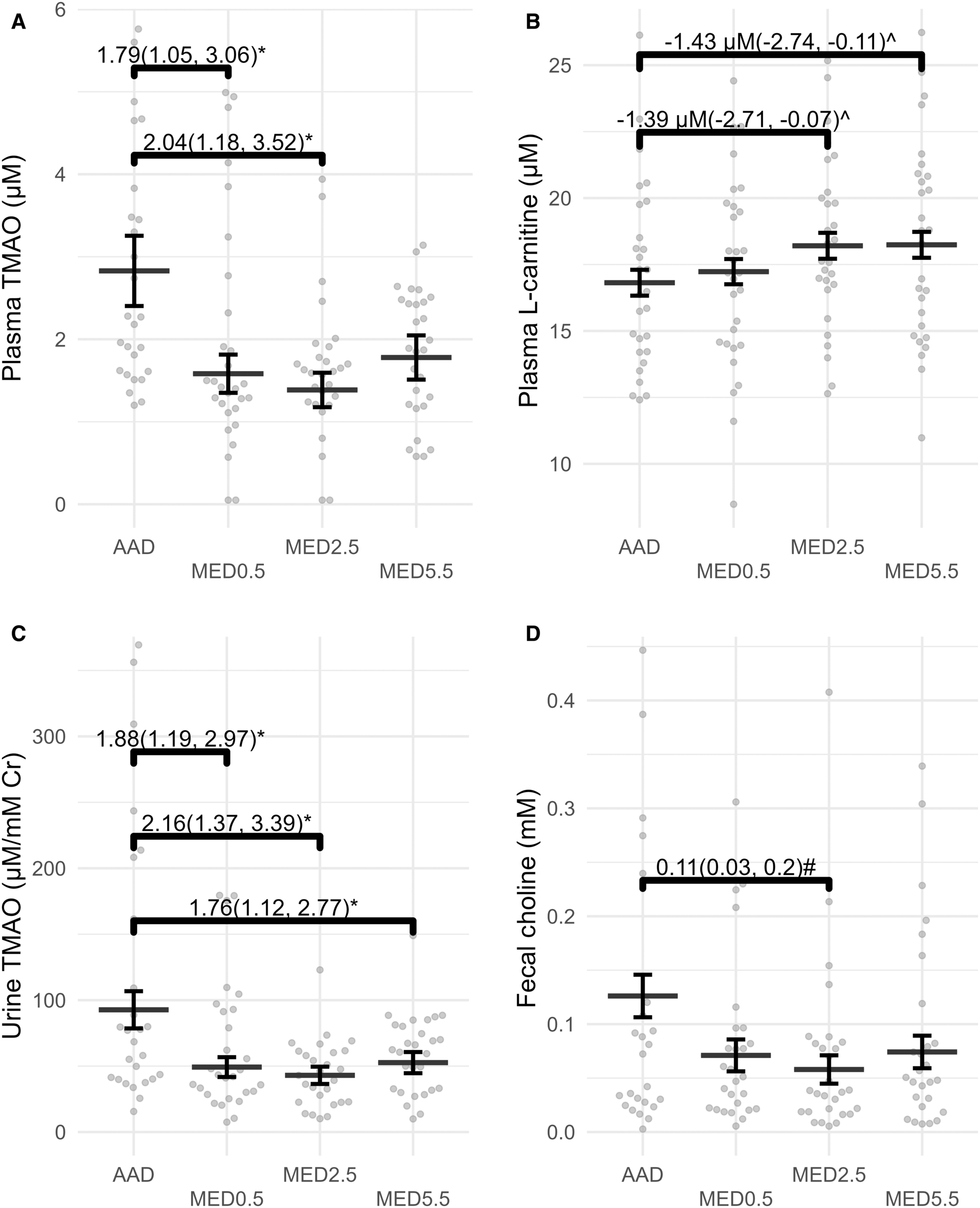

The results may surprise you if you have been told that any beef will automatically raise risk. When participants ate the Mediterranean style menus with either 0.5 ounce or 2.5 ounces of lean beef per day, their blood TMAO levels were lower than when they ate the American style plan with 2.5 ounces of fattier beef.

When people followed the American style plan with regular beef or the Mediterranean style plan that packed in 5.5 ounces of lean beef a day, TMAO levels were similar. In other words, the overall quality of the menu seemed to matter more than simply counting how many ounces of beef appeared on the plate.

“We chose 2.5 ounces of lean beef because that approximates the amount of beef that the average American consumes each day,” says doctoral candidate Zachary DiMattia, the lead author. “This study suggests that, in the context of a healthy dietary pattern, people may be able to include similar amounts of lean beef without increasing their TMAO levels. If people eat reasonable portions of lean, unprocessed beef as part of a Mediterranean-style diet, we would not expect this specific marker of cardiovascular disease risk to rise.”

Urine tests told a similar story. The Mediterranean style plans generally led to lower TMAO excretion than the American style plan. That pattern held even with some variation in the portion of lean beef.

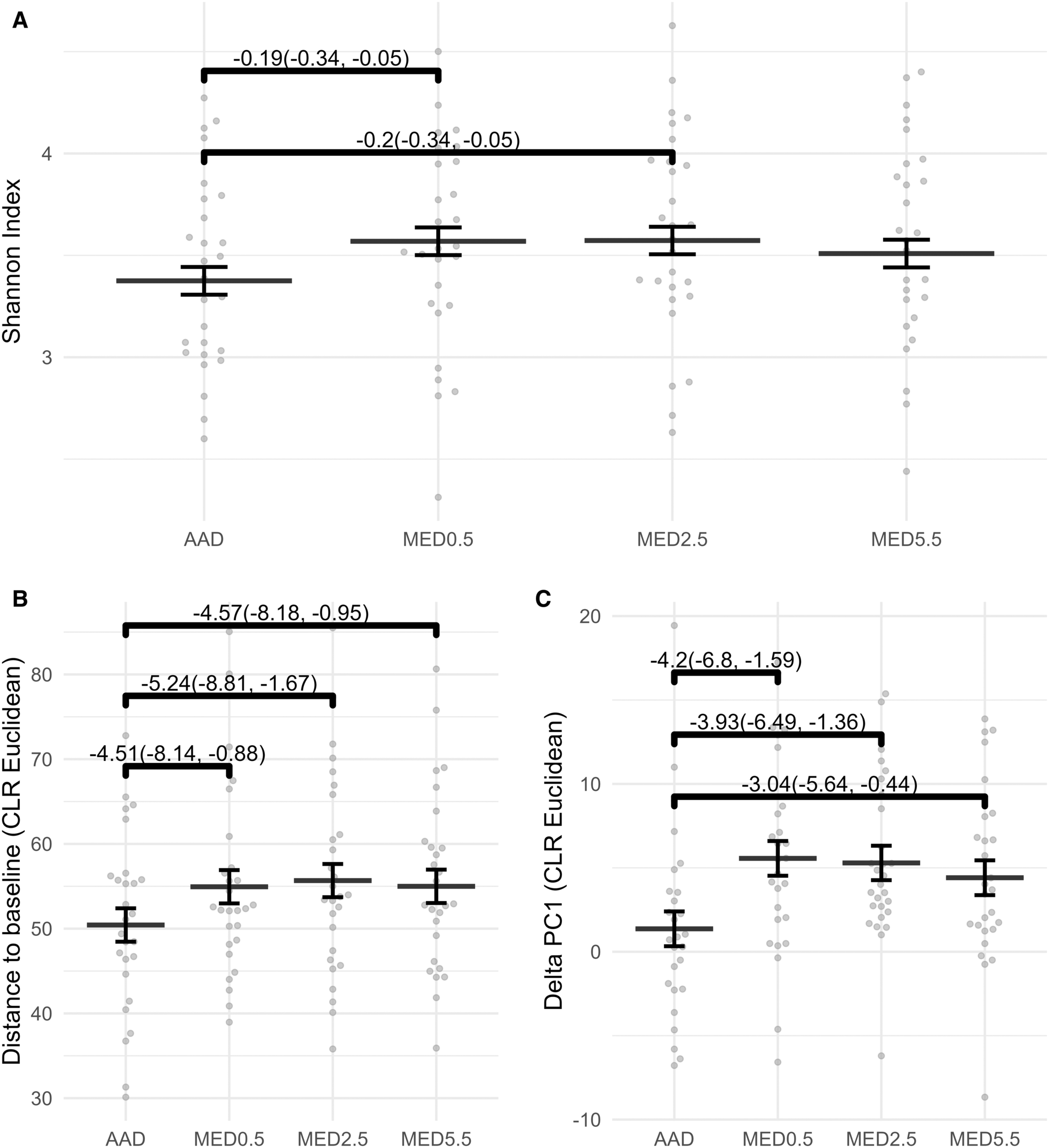

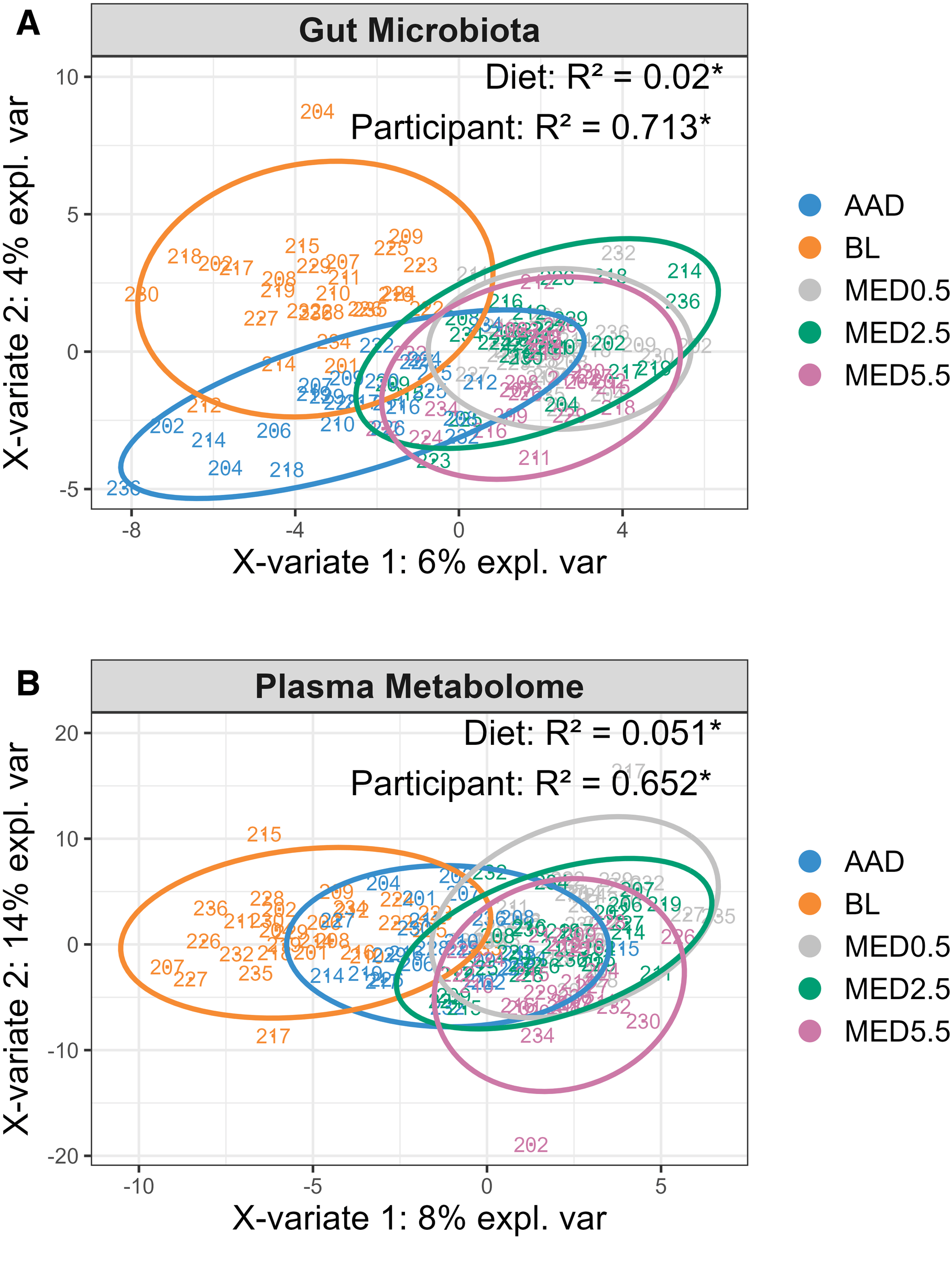

The research team also wanted to know how these eating patterns shaped the gut microbiome. A more diverse community of gut bacteria tends to be associated with better health.

Compared with the American style menu, all three Mediterranean style plans increased microbial diversity. That was true whether the lean beef serving was tiny, moderate, or fairly large. The finding suggests that when you load your plate with vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and healthy fats, you support a richer gut ecosystem even if you still include some red meat.

The scientists caution that they do not yet know exactly how gut microbes, diet, and TMAO production interact. Different people harbor different microbial species, and those communities may respond in distinct ways to the same foods. The study points to a promising direction, but it does not yet map out every step in that chain.

Petersen’s lab has used this same feeding trial to look at other measures of heart and blood vessel health. Earlier this year, her group reported that a Mediterranean style pattern that included lean beef led to lower blood pressure than the American style menu.

The team also stepped back to consider the broader research on red meat and TMAO. Doctoral student Fatemeh Jafari led a review of previous trials that tracked how TMAO responds to beef and other red meat. “The literature review highlighted the complicated nature of TMAO,” Petersen notes. Just under half of the studies found that red meat increased TMAO, while the rest showed no clear rise in response to beef.

Together, these findings support a more layered message. People have long been warned to limit beef intake because higher beef consumption has been linked to risk of heart disease. These newer data suggest that moderate consumption of lean, unprocessed beef as part of a healthy pattern does not worsen several key risk factors, at least in young adults.

If you enjoy the occasional steak, this research offers some reassurance, but it does not grant a free pass. The people in this trial ate carefully controlled portions every day, not a giant steak once a week. “This evidence does not mean you can necessarily eat a week’s worth of beef — for example, a single, 17.5-ounce steak — at one time and see the same results,” Petersen says.

The recommendation also does not cover fatty cuts or processed meats like bacon, sausage, or salami. Those products often contain more saturated fat and sodium and have been tied more consistently to higher heart disease risk.

The study sample also matters. These participants were relatively young and healthy. The team notes that “further research is needed in older people or anyone with elevated heart disease risk.”

For now, the basic advice remains familiar. Make fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and unsalted nuts the foundation of your meals. Use olive oil and other unsaturated fats instead of butter when you can. If you choose to eat beef, pick lean, unprocessed cuts, keep portions modest, and place them within a mostly plant based, Mediterranean style pattern.

It is also worth noting who paid for the research. Funding came from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a contractor to the Beef Checkoff, and from Penn State. The authors followed standard scientific procedures, but knowing the sponsor helps you interpret the findings with a critical eye.

For people who like red meat, this work suggests a realistic path that does not require cutting beef completely. You can focus on the overall pattern first: more produce, more whole grains, more healthy oils, and less saturated fat. Within that framework, a small daily serving of lean, unprocessed beef appears compatible with stable or even lower TMAO levels and a more diverse gut microbiome.

For clinicians and dietitians, the study supports a shift away from single food rules toward pattern based guidance. Rather than telling patients never to eat beef, providers can encourage them to swap to lean cuts, trim visible fat, avoid processed meats, and build the rest of the plate around plants.

For researchers, the work highlights TMAO as a complex, context dependent marker rather than a simple switch that flips whenever someone eats meat. Future studies will need to test older adults and people with existing heart disease, and they will need to follow participants long enough to see whether differences in TMAO and gut microbes translate into fewer heart attacks and strokes.

At a broader level, the findings may ease some tension between cultural food traditions and modern health advice. Many families value beef for taste, heritage, or convenience. Showing that moderate, careful use of lean cuts can fit into a heart healthy pattern may make it easier for people to adopt and keep healthier overall habits, which is what truly drives long term benefit.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Modest amounts of lean, unprocessed beef can be heart friendly, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.