Look up on a dark night and the stars seem scattered at random. Step back in scale, though, and the Universe looks nothing like a loose dusting. On its largest stretches, matter forms a vast web. Thick clusters rise where threads meet. Long filaments bind them together. Immense voids lie between, empty as oceans without water.

Astronomers have long thought these filaments act like space highways. Gas, dark matter and entire galaxies drift along them toward packed hubs called nodes. But many scientists suspected something more. These structures should not simply carry matter. They should also twist. Now, for the first time in striking detail, researchers have caught one of these giant threads in the act of spinning.

An international team led by the University of Oxford reports the discovery of a rotating cosmic filament that stretches for about 50 million light years. Inside it sits an unusually narrow chain of galaxies glowing in radio light. The findings, published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, reveal one of the clearest cases yet of a large-scale structure that both rotates and lines up the spin of its galaxies.

The discovery began in South Africa’s Karoo region, where 64 white radio dishes form the MeerKAT telescope. Each dish listens for faint radio signals from space, including a special signal from atomic hydrogen. Hydrogen is the most common element in the Universe and the basic fuel for stars.

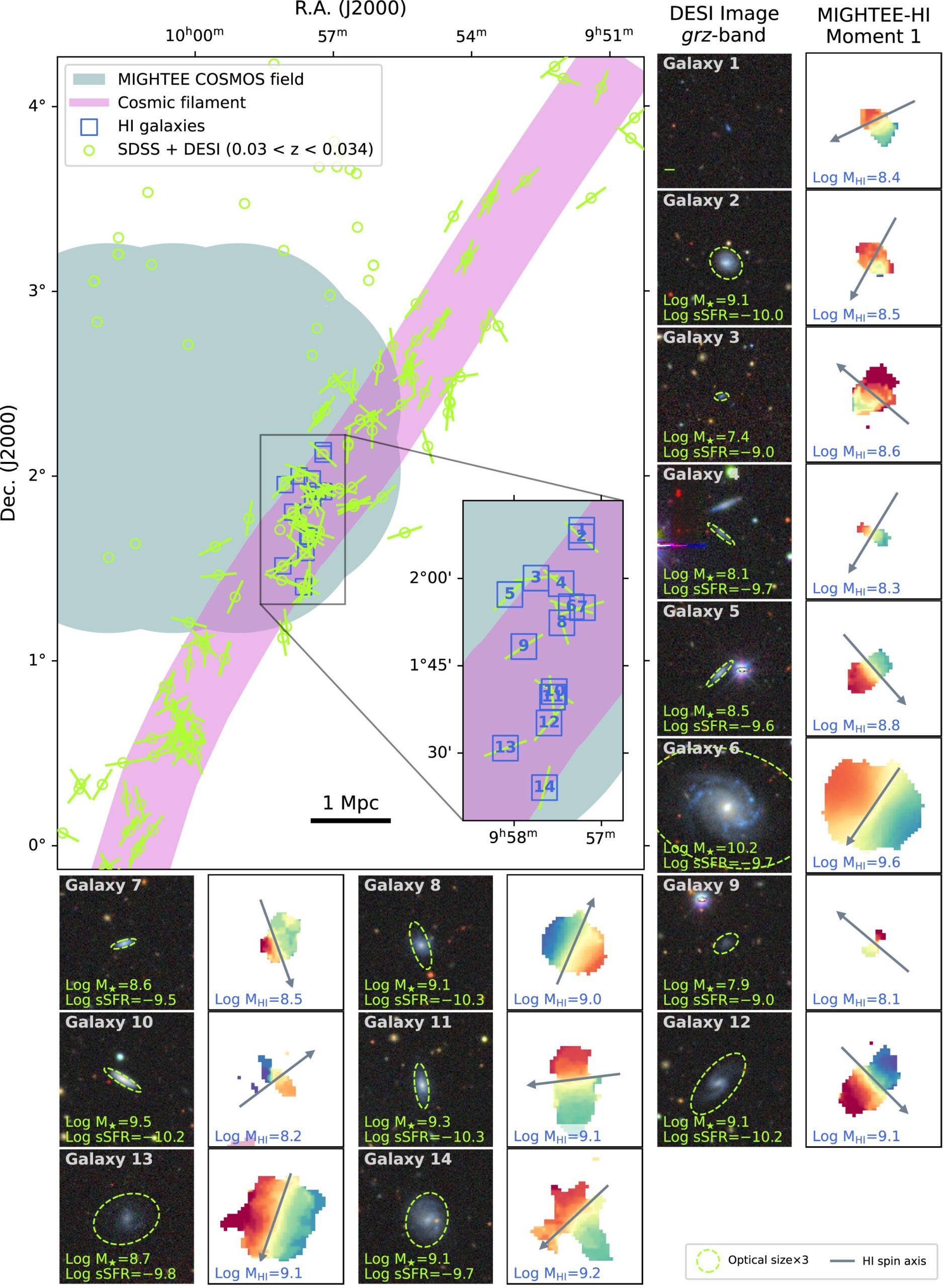

The team used data from a deep MeerKAT project called MIGHTEE to scan a well-studied patch of sky known as COSMOS. In that radio map, they noticed something odd. Fourteen galaxies rich in hydrogen gas were strung together in a thin line, about 5.5 million light years long and only 117,000 light years wide. All were moving at nearly the same speed.

“It stood out right away,” said Dr. Lyla Jung of Oxford’s Department of Physics. “You do not expect to see a line of galaxies this narrow and tidy by chance.”

But the radio view covered only part of the sky. To see the full structure, the team turned to optical data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, or DESI. These projects measure the distances of galaxies by splitting their light into colors.

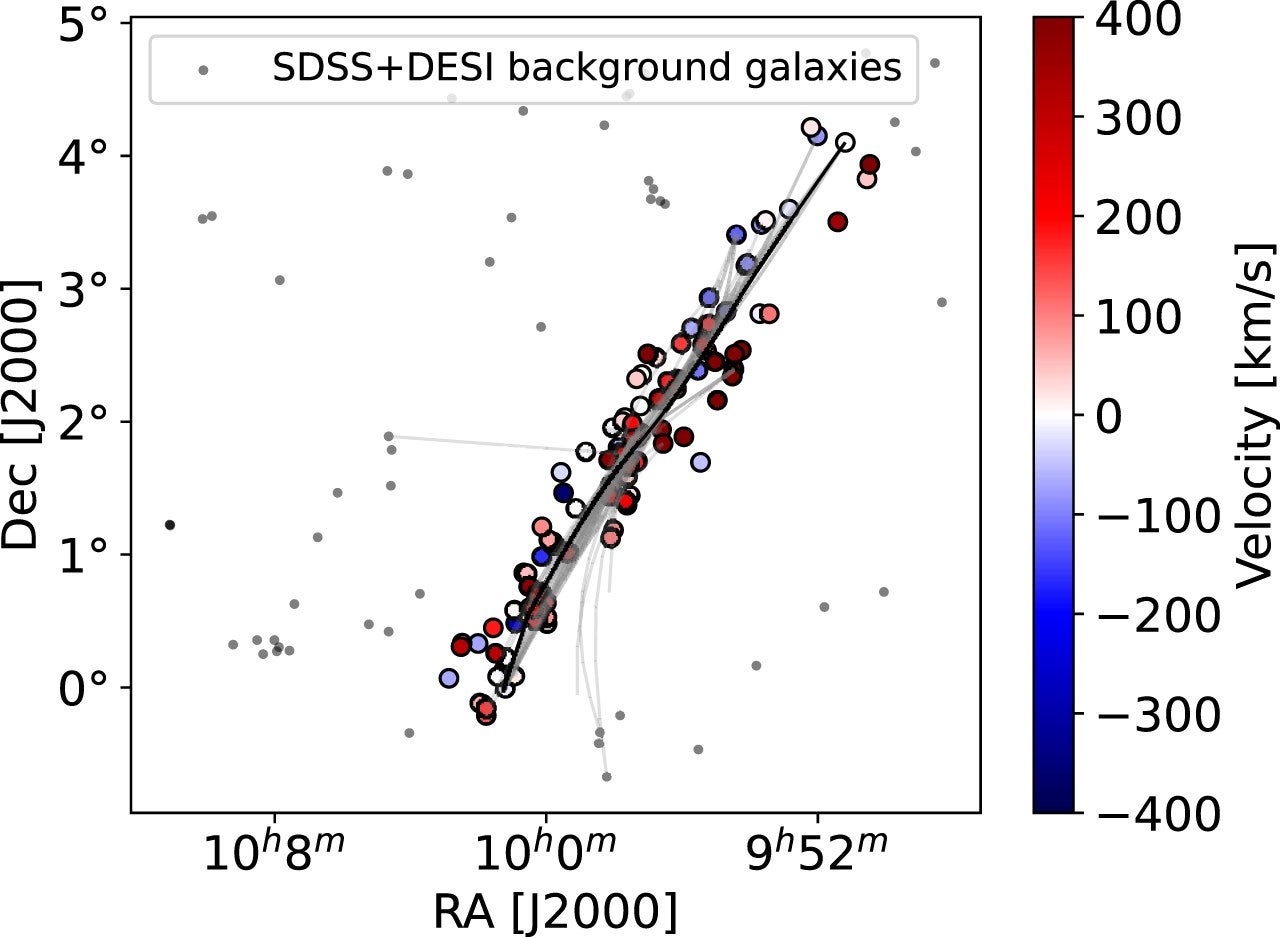

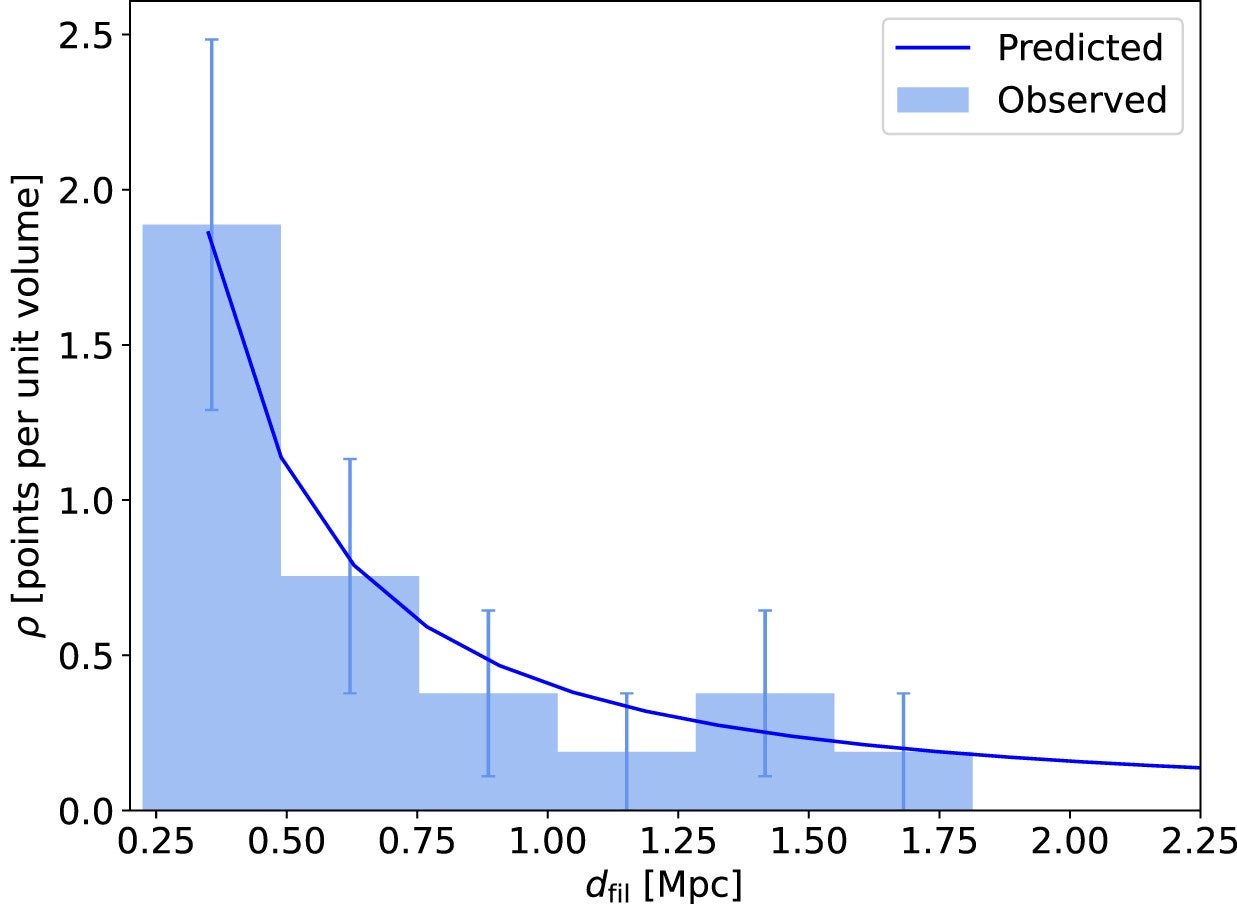

When the researchers added that information, the picture expanded fast. The skinny hydrogen strand lay inside a much larger filament holding more than 280 galaxies. This giant thread runs roughly 50 million light years from end to end. The narrow radio chain sits like a bright wire within a thicker cosmic cable.

The real surprise came when the team studied how the galaxies were turning. Galaxies rotate, just like planets and stars. Theory holds that their spin comes from gentle tugs in the young Universe, long before galaxies fully formed.

To test the idea, the scientists measured the shapes and angles of galaxies seen in optical images. From this, they worked out how each one likely spins in space. Because you cannot tell which side of a distant galaxy is closer, the team ran thousands of trials, flipping each galaxy’s tilt direction to see how the results would change.

The answer held steady. Most of the galaxies spin in the same direction as the filament around them.

“What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin direction and large-scale rotation,” Jung said. “You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform, the cosmic filament, is rotating too.”

The team also checked whether the filament itself was moving as a whole. They looked at galaxy speeds on each side of the thread’s center. One side showed galaxies drifting away from Earth. The other side leaned toward Earth. This pattern fits with a slow, bulk rotation around the filament’s length.

From this motion, the researchers estimated a rotation speed of about 110 kilometers per second. They also worked out that the densest inner region of the filament has a radius of about 50 kiloparsecs, or 163,000 light years.

This filament appears young and calm by cosmic standards. The galaxies inside it hold large reserves of hydrogen and show low levels of chaotic motion. Scientists describe such systems as “dynamically cold,” meaning they have not been shaken much by collisions or close passes.

Dr. Madalina Tudorache of the University of Cambridge and Oxford says this matters. “This filament is a fossil record of cosmic flows,” she said. “It helps piece together how galaxies gain their spin and grow through time.”

Hydrogen-rich galaxies are especially useful in this work. Gas is easily stirred, so it traces motion more clearly than stars alone. Where gas streams go, stars often follow later. Seeing hydrogen along the filament shows that matter is still drifting inward, feeding galaxies as they build new suns.

The study also found that galaxy behavior changes along the filament. In crowded sections, where galaxies pack closer, their spins lose order. In quieter stretches, alignment stays strong. Encounters and mergers seem to scramble the tidy pattern near dense zones.

The strong lineup seen here is sharper than most computer models predict. That could mean cosmic filaments steer galaxy spin more powerfully, or for longer, than scientists thought.

This also carries a warning. Many upcoming missions, including the European Space Agency’s Euclid spacecraft and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, will measure how galaxy shapes bend under gravity. This effect, called weak lensing, helps reveal dark matter and dark energy.

If galaxies line up naturally within cosmic structures, that signal can muddy the lensing picture.

“Strong alignments like this can mimic the effect we use to map dark matter,” Jung explained. “If we do not account for them, results could be skewed.”

Professor Matt Jarvis of Oxford, who leads the MIGHTEE project, said the work shows the value of teamwork. “This really demonstrates the power of combining data from different observatories,” he said. “You gain insight you could never reach with one view alone.”

What was once a faint thread in radio waves now tells a larger story. It shows that the Universe does not just grow, it turns. And in that slow cosmic spin, galaxies receive both their fuel and their motion.

Understanding how galaxies gain their spin helps scientists trace the flow of matter across the Universe. This knowledge sharpens models of galaxy growth and star formation.

The discovery also improves planning for future missions that study dark matter and dark energy. By learning how natural galaxy alignments affect measurements, researchers can refine their tools and avoid false signals.

In a broader sense, the work reveals how deeply connected cosmic systems are. Filaments do not merely hold galaxies in place. They shape their motion, life cycle and history. That insight brings scientists closer to understanding how the Universe became the place where stars, planets and eventually life could form.

Research findings are available online in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post At 50 million-light-years long, scientists discover one of the universe’s largest structures appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.