When the Black Death tore through Europe in 1347, it felt like the end of the world. Entire villages emptied. Bells rang without pause. In some places, more than half the people died within months. History books often reduce the catastrophe to a single cause: a tiny bacterium called Yersinia pestis. But that germ was only the final spark.

New research shows the disaster began years earlier with fire and ash from distant volcanoes, a sudden shift in weather, empty fields, and a desperate hunger that pushed cities to search far beyond home for food. Step by step, those forces lined up and opened a door for the deadliest outbreak in European history.

Long before the disease arrived, the climate already had turned against Europe. Ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica point to a large volcanic blast around 1345, maybe several close together. Researchers estimate the ash and gases released were more than twice as strong as those from Mount Pinatubo in 1991.

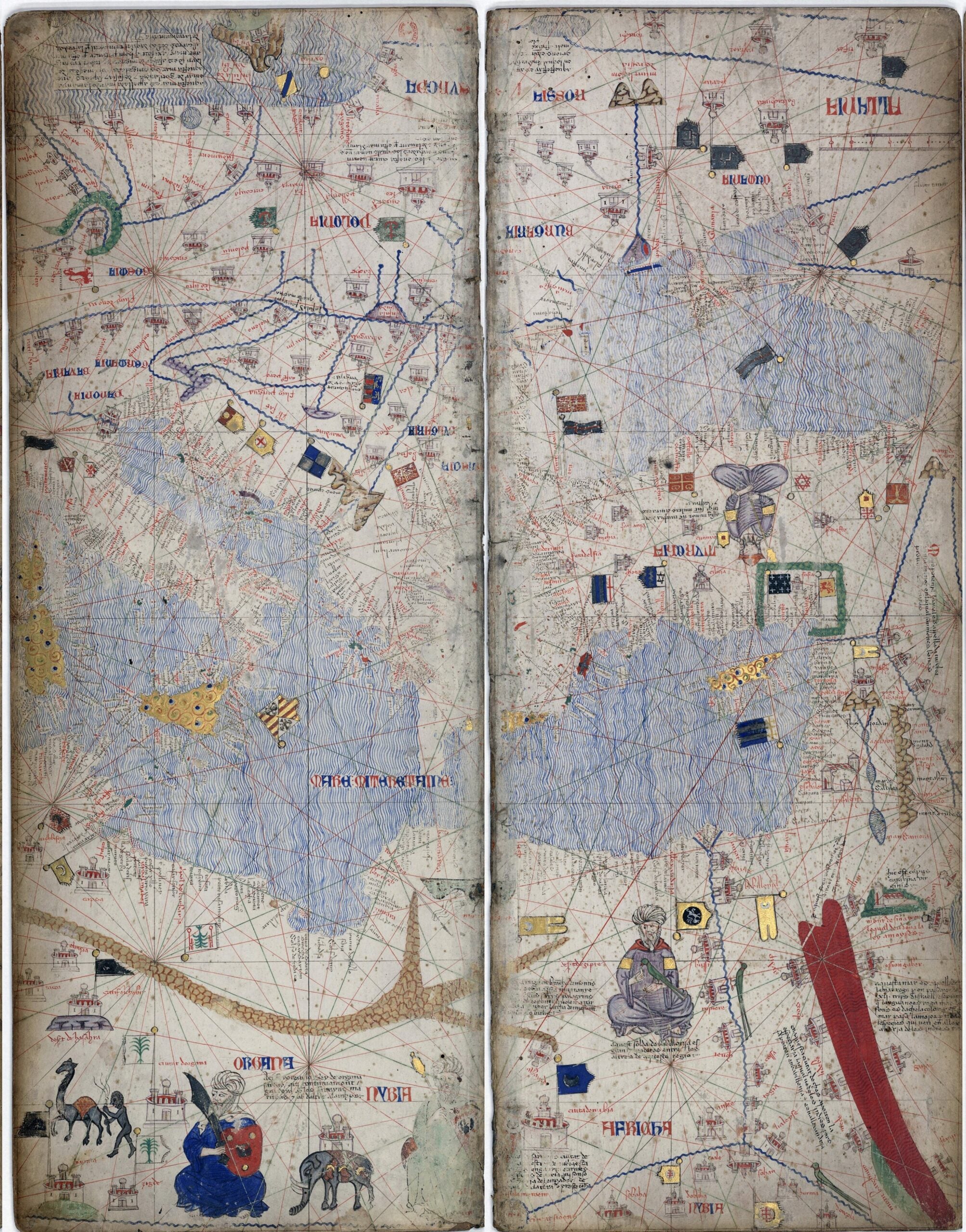

That dust cloud drifted into the upper air and spread across the Northern Hemisphere. It blocked sunlight, cooled the land, and changed rainfall patterns. Tree rings from tall pines in the Spanish Pyrenees tell the same story. They show “blue rings” in 1345 and 1346, a rare sign of cold and wet summers that stunted growth. Researchers from the University of Cambridge and the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig used this and other data to rebuild the climate of the 1340s.

Writers from Italy to China also noticed the shift. They wrote about darkened skies, strange fog, and dim moons. Some described lunar eclipses that looked wrong, as if the moon had been stained with ash. Those reports match the pattern of volcanic haze hanging in the air.

Cold summers and strange weather soon crushed agriculture. In northern Italy, vineyards produced little or nothing. Floods swept through the Po Valley. Heavy rains ruined fields in Tuscany and Lazio. Farther east, harsh winters and dry seasons battered crops across the Middle East. Locusts finished what the weather had started.

By 1346, hunger had spread across Spain, France, Italy, Egypt, and the Levant. Grain prices soared. In some regions, wheat in 1347 cost more than it had in eighty years. Governments panicked. Leaders outlawed exports, seized food for storage, and punished hoarders. Some cities faced unrest as people fought over bread.

Construction also slowed across much of Europe. In central regions, building fell to its lowest level in centuries. It was a clear sign that money, labor, and confidence were vanishing.

Italian cities felt the crisis with special force. Places like Venice, Genoa, Florence, Siena, and Bologna were crowded and hungry. Only a few large cities could feed themselves. The rest depended on complex trade systems built over more than a century.

Grain was the lifeblood of these city-states. Officials ran public storehouses and watched every shipment. They set prices, banned exports, and taxed mills and bakeries. Keeping people fed was as important as defense.

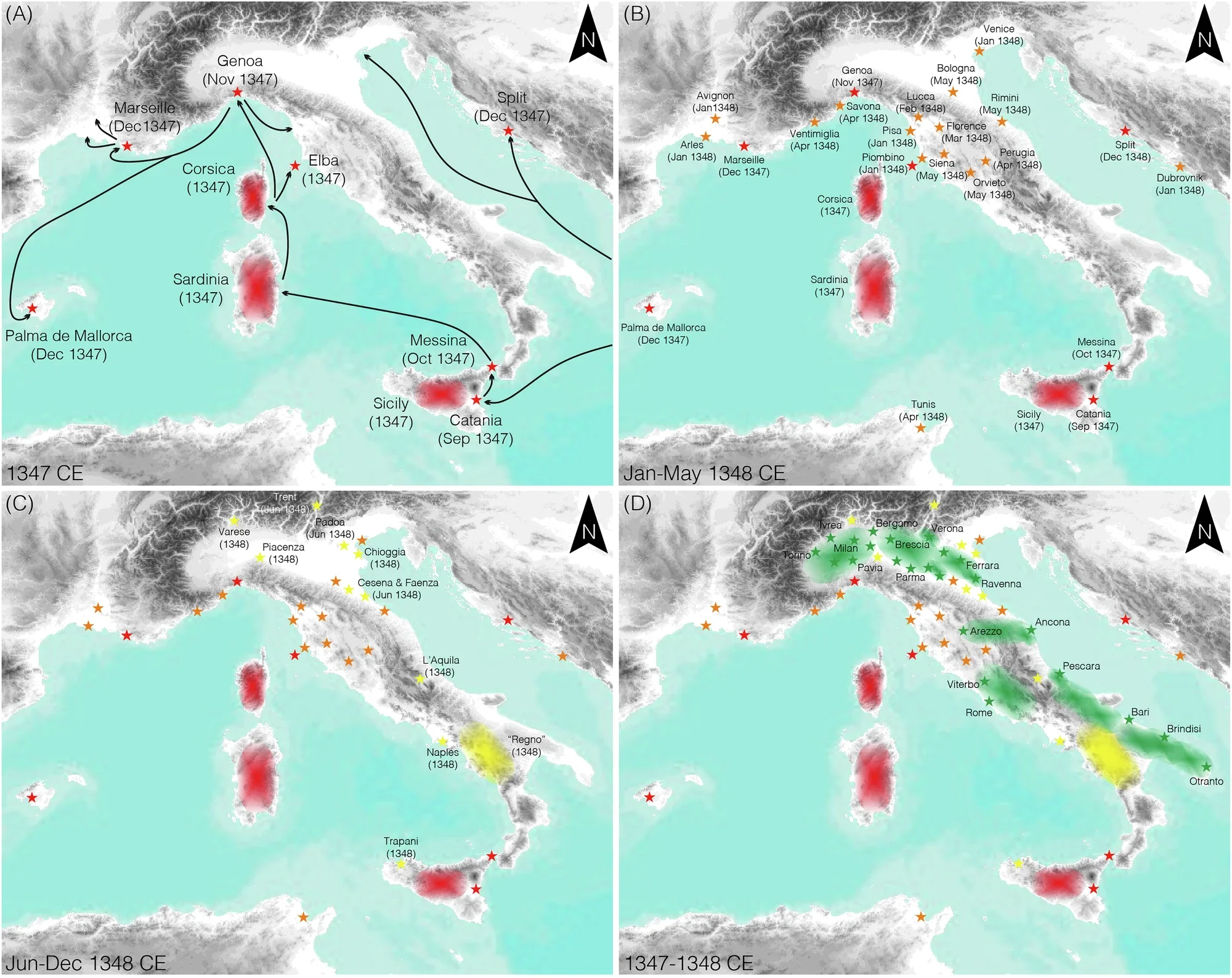

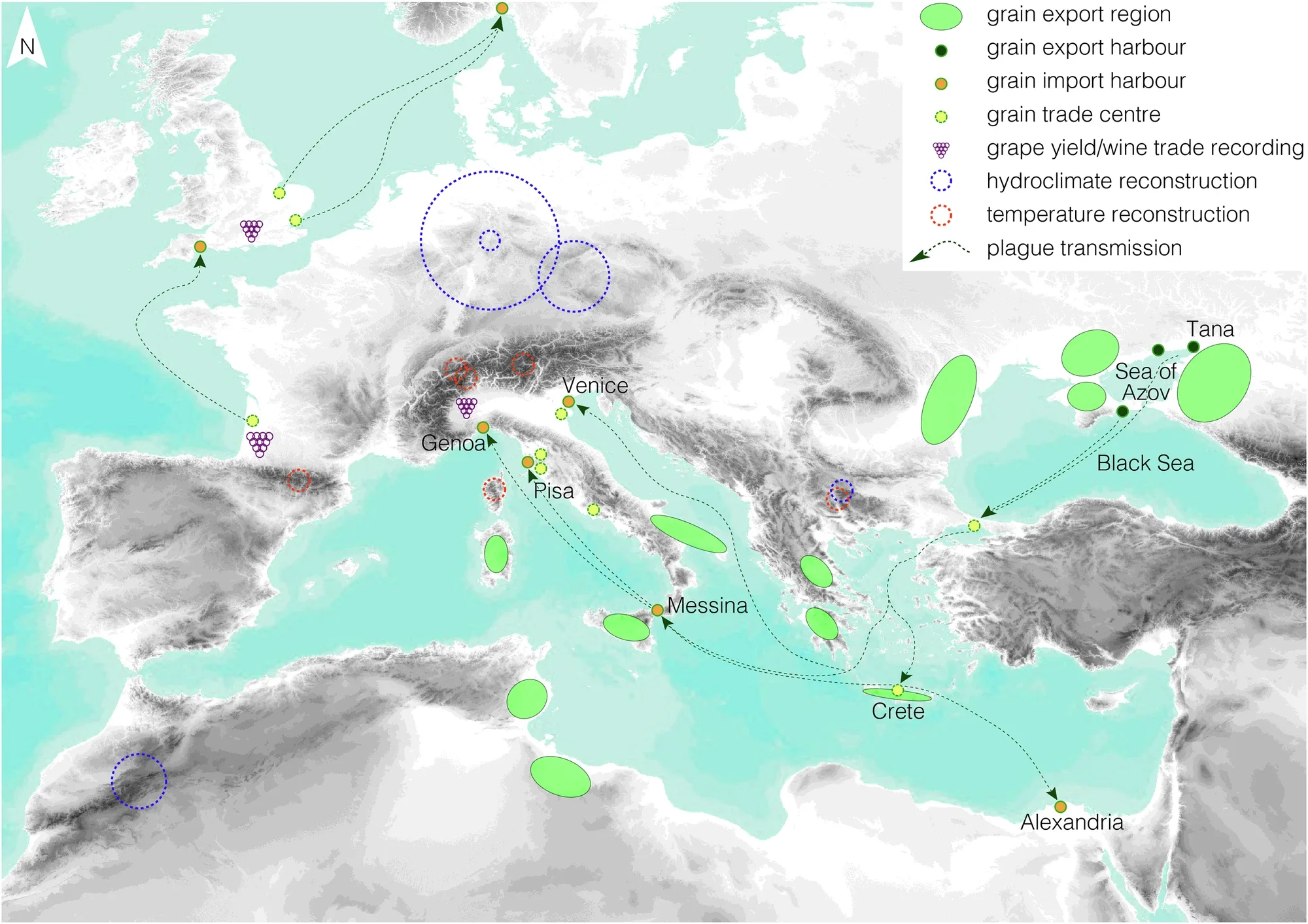

When local harvests failed in 1345 and 1346, the cities turned first to southern Italy and nearby lands. But the famine widened, and those sources dried up. Then merchants looked even farther away, across the Black Sea to lands ruled by the Mongol Golden Horde. In April 1347, a trade ban was lifted, and ships rushed north for grain.

Venetian records later would say that Black Sea grain “saved the city” from starvation. In the summer and fall of 1347, ships raced back loaded with wheat, rye, and barley, bound straight for Mediterranean ports.

Those shipments carried more than food.

Yersinia pestis, the germ behind the plague, lives in wild rodents and spreads through fleas. The insects feed on infected animals and can survive without blood if they have dust and organic scraps to eat. Grain cargo turned out to be perfect shelter.

Researchers argue those fleas likely rode inside sacks of grain. The first cases in Venice appeared less than two months after the last ships arrived. Soon, the disease followed trade routes inland. Cities that received Venice’s soon had outbreaks too.

Some patterns stand out. Padua fell ill after fresh grain arrived from Venice in early 1348. Sales from Venetian stores may have carried the disease north into alpine valleys. Meanwhile, cities that did not import Black Sea grain that year, including Rome, Milan, and parts of the Po plain, escaped the first wave.

Ports tied to Genoese grain routes were not as lucky. Marseille and Palma de Mallorca recorded cases by late 1347. Smaller harbors followed in 1348. Food had kept famine away but invited the plague inside the gates.

“This is something I’ve wanted to understand for a long time,” said Professor Ulf Büntgen of Cambridge’s Department of Geography. “What were the drivers of the onset and transmission of the Black Death, and how unusual were they?”

Büntgen’s team uses tree rings to read the climate of the past. He worked with Dr. Martin Bauch, a medieval historian at GWZO, to connect weather, food, and disease.

“We wanted to look at the climate, environmental and economic factors together,” Bauch said. “So we could more fully understand what triggered the onset of the second plague pandemic in Europe.”

Their findings appear in the journal Communications Earth & Environment. The study pulls together ice cores, trees, price records, shipping logs, and old letters. It paints the clearest picture yet of how nature and trade joined forces.

Between 1347 and 1353, the Black Death killed millions across Europe. It changed labor, faith, and power for generations. It also delivered one of history’s first global warnings.

Trade networks that saved lives from hunger also spread disease. Climate disasters in one place sent shock waves through others. A threat born in wild rodents thousands of miles away found a path into crowded cities.

“In so many towns, you still see the scar,” Büntgen said, pointing to Cambridge’s Corpus Christi College, founded after plague tore through the city. “There are similar stories everywhere.”

Bauch adds that studying who fell ill, and who did not, helps explain later outbreaks. “The climate-famine-grain connection has potential for explaining other plague waves,” he said.

The study leaves little doubt that the Black Death was not random. It was the result of rare timing and human choices colliding with natural forces.

The research offers a warning for the present. Climate shifts can break food systems. Long supply chains can spread harm as fast as they spread help. When disease lives in animals, human trade and travel can carry it far and fast.

The findings suggest modern health planning should not stand alone. It must connect climate science, agriculture, trade, and disease control. Early warnings about drought or crop failure may also serve as warnings about rising disease risk. History shows that hunger can change travel routes and the paths of infection.

Understanding the past may help keep it from repeating. The Black Death reveals how closely climate and health are linked. In a warming world, that lesson matters more than ever.

Research findings are available online in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists reveal what triggered the Black Death plague in Europe appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.