Nearly 4.5 million years ago, two enormous, blazing stars swung close to the solar system. They did not touch the sun, but they came close enough to leave a permanent mark on the thin mist of gas that surrounds our cosmic home. That mark still lingers today, written in invisible electric charges carried by atoms drifting between the stars.

New research led by astrophysicist Michael Shull of the University of Colorado Boulder shows how that ancient encounter changed the space around the sun. The work, published in The Astrophysical Journal, explains why the clouds just beyond the solar system still carry strange electric fingerprints. Those signs suggest that Earth’s corner of the galaxy is anything but calm.

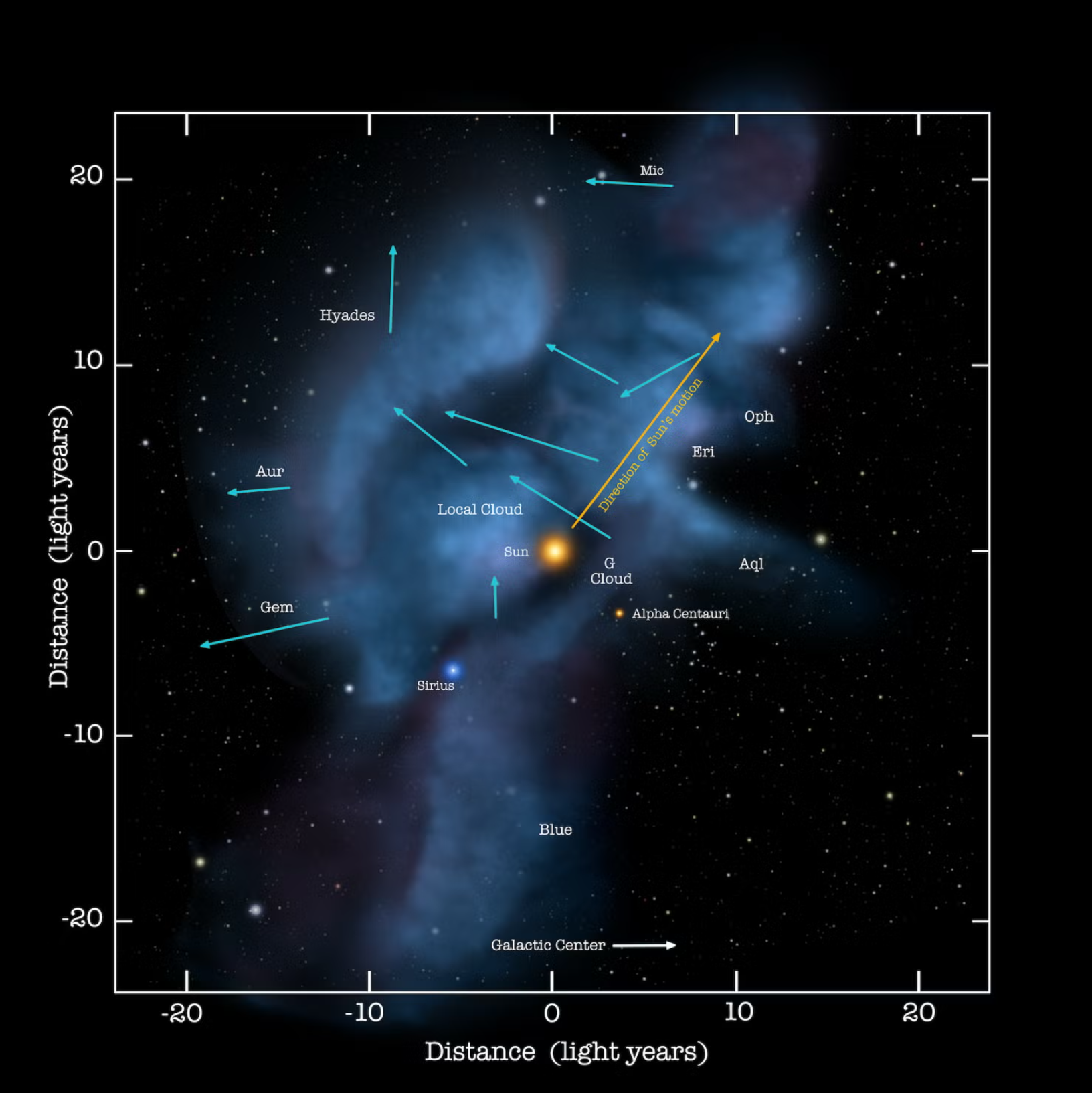

Space near the sun is not empty. It holds about 15 shifting clouds of thin gas within roughly 30 to 50 light-years. These clouds are warm and partly electrified. About one-fifth of their hydrogen atoms and nearly half of their helium atoms have lost electrons. That pattern has puzzled scientists for decades.

The sun is moving through this region at more than 58,000 miles an hour. As it travels, these clouds shape the radiation that reaches the edges of the solar system. Understanding them is not just math. It helps explain why Earth receives the kind of space radiation it does today.

“The fact that the sun is inside this set of clouds that can shield us from that ionizing radiation may be an important piece of what makes Earth habitable today,” Shull said.

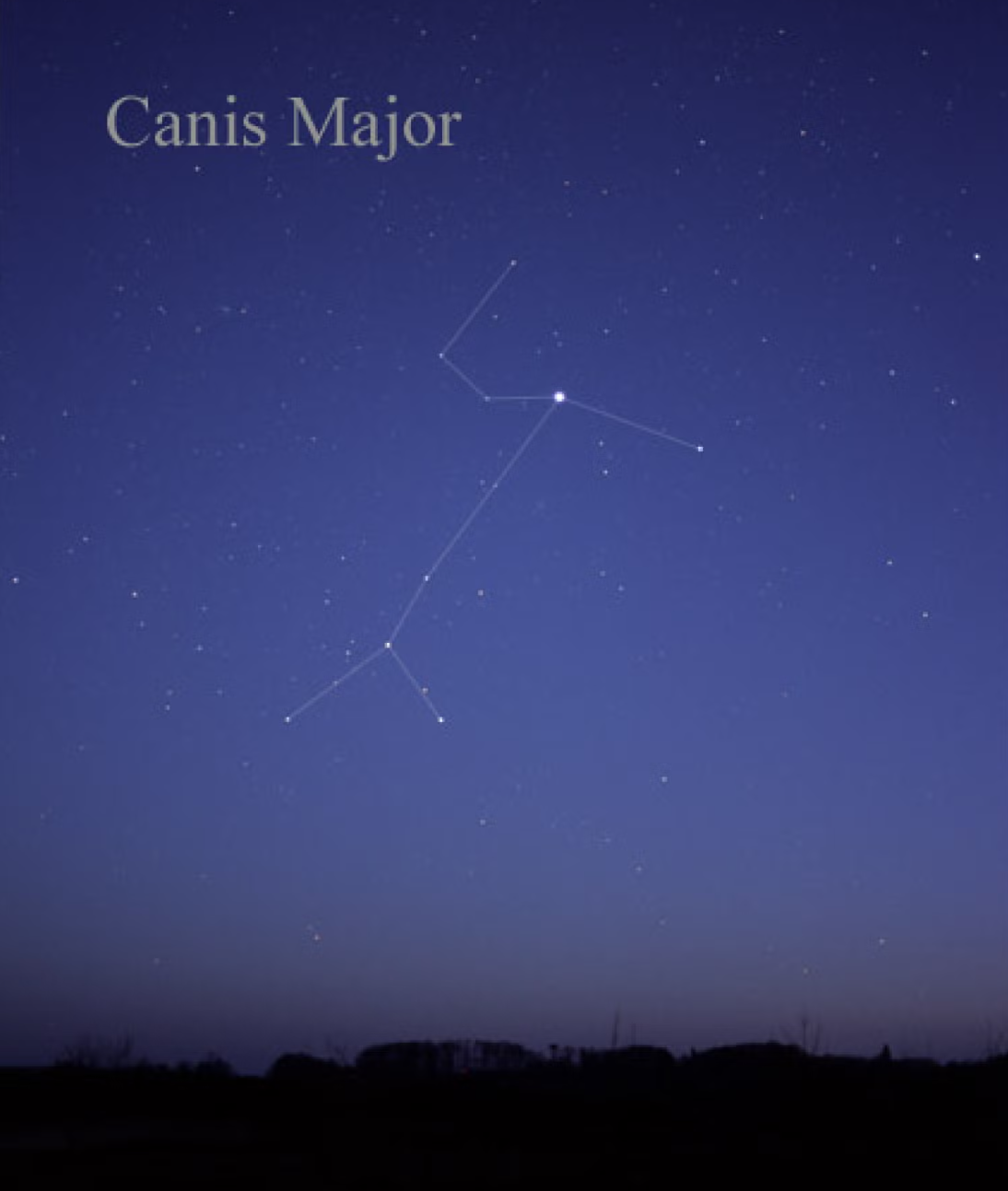

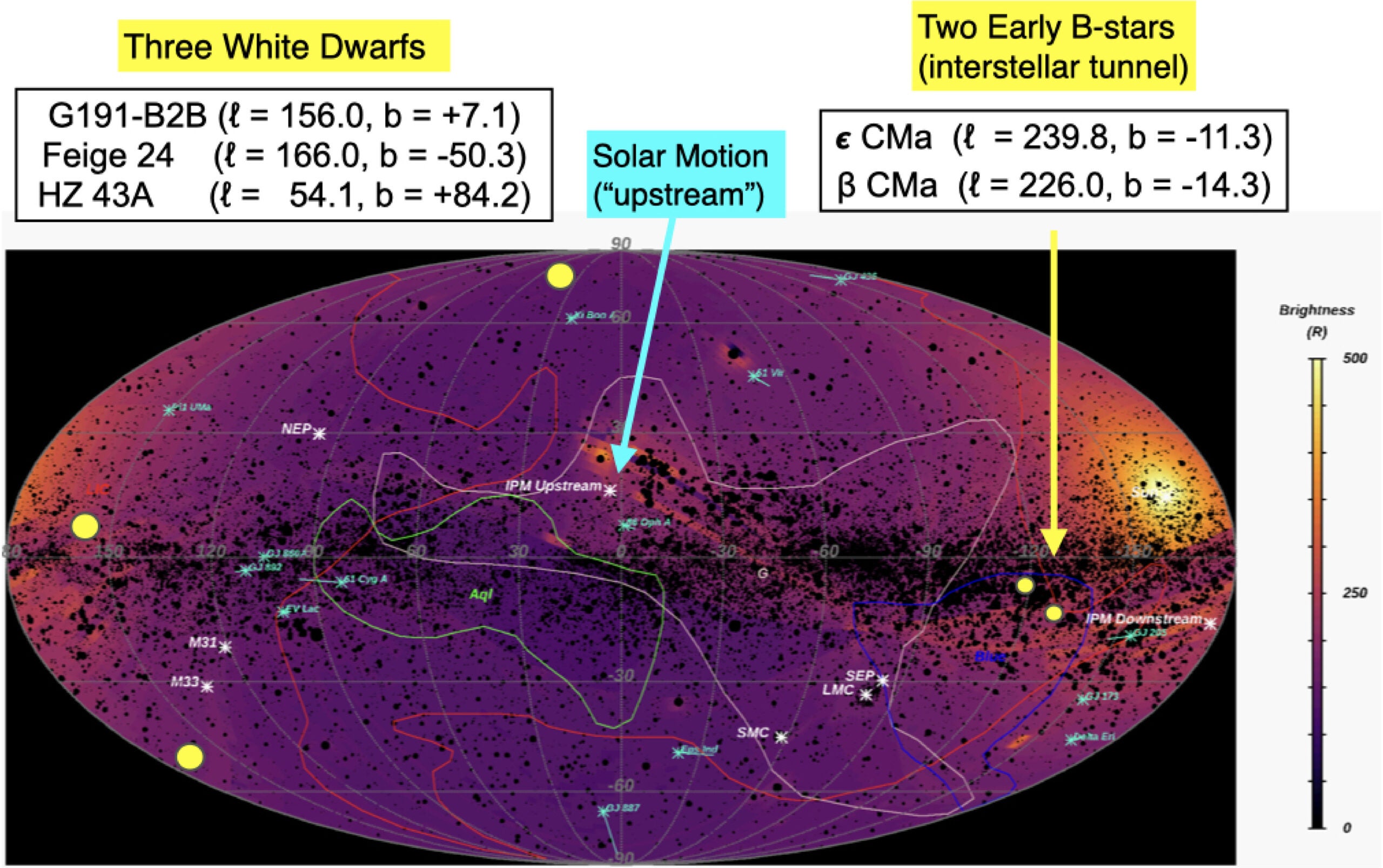

The research focuses on two bright giants in the constellation Canis Major: Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris. They now sit more than 400 light-years from Earth. Millions of years ago, they were far closer.

Using motion data from the Hipparcos satellite, the team traced their past paths through space. Both stars passed within about 30 to 35 light-years of the sun around 4.4 million years ago. In cosmic terms, that is a near miss.

At that time, the stars would have glowed with terrifying brilliance. Shull said they may have appeared four to six times brighter than Sirius does today. Their intense ultraviolet light blasted nearby gas clouds, ripping electrons away from hydrogen and helium atoms.

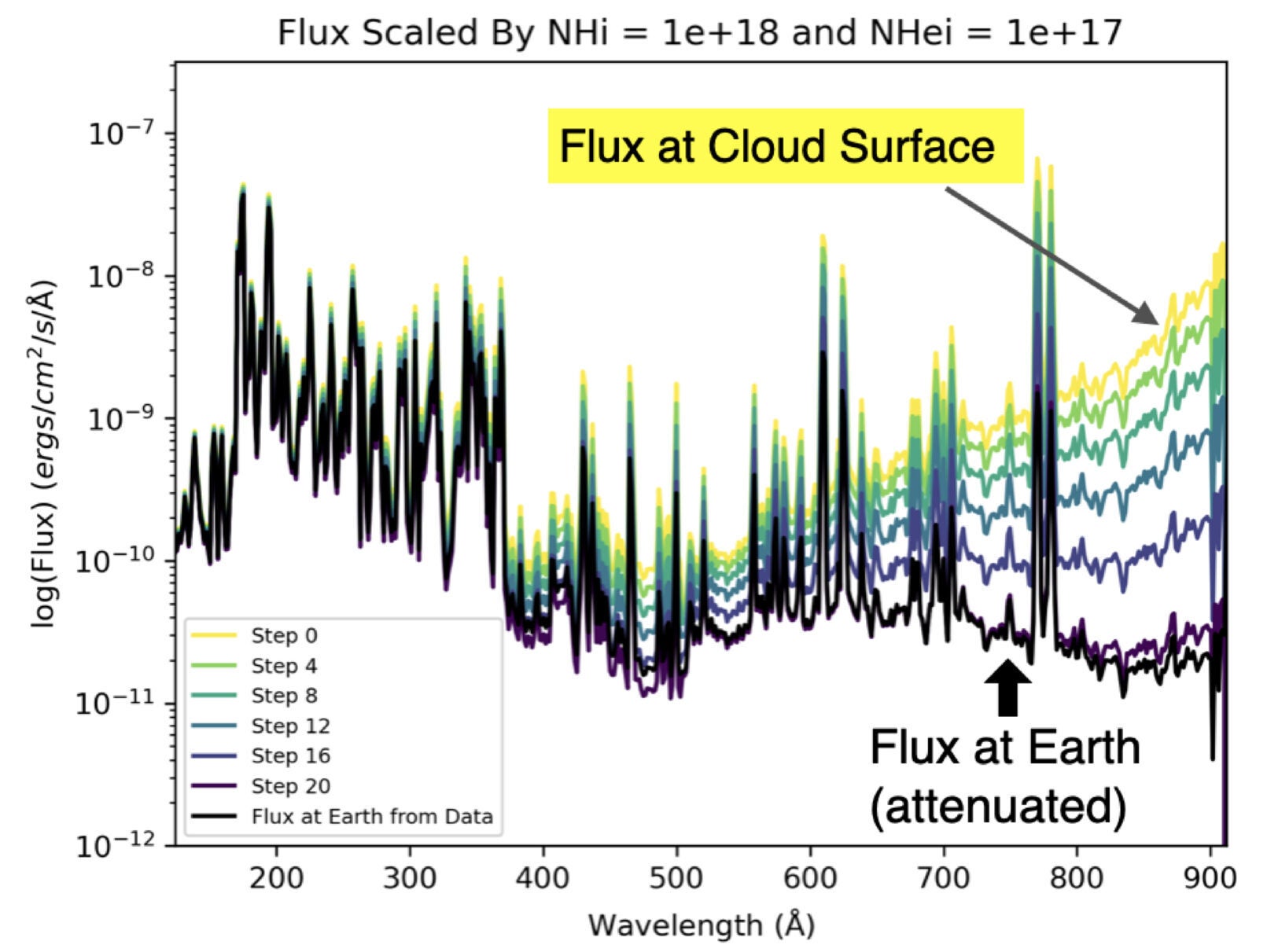

This process is known as ionization. It leaves atoms with an electric charge and changes how clouds behave. The team found that the odd balance of charged hydrogen and helium around the solar system fits perfectly with the idea that these stars once passed close by.

The sun, the stars, and the clouds do not stay in place. All drift through the galaxy like leaves in a river.

“It’s kind of a jigsaw puzzle where all the different pieces are moving,” Shull said. “The sun is moving. Stars are racing away from us. The clouds are drifting away.”

Still, the scars from that flyby remain.

The stars did not work alone. The area around the sun also lies inside a vast region called the Local Hot Bubble. This is a cavity filled with gas heated to millions of degrees. Astronomers believe it formed after 10 to 20 giant stars exploded long ago.

Those blasts cleared out much of the dust and left behind superheated gas. Even today, that gas gives off ultraviolet and X-ray light. That glow bakes the nearby clouds from the inside.

The team modeled how all known sources of radiation work together. They included the two B-type stars, three aging white dwarf stars, and the glow from the hot bubble. The models show that the bubble plays a major role, especially for helium.

The pattern seen in nearby clouds calls for more energy to affect helium than hydrogen. Starlight alone cannot explain that. When the hot bubble is added, the math finally works.

Heat and light from both the stars and the bubble helped create the strange mix of charged atoms now floating around the sun.

The clues left by this event will not last forever. Over time, charged atoms in space regain their lost electrons. As that happens, the unusual mix of hydrogen and helium will fade.

The stars that caused much of this drama are nearing their own ends. Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris are about 13 times more massive than the sun and will burn out quickly. Shull estimates they may explode as supernovas in the next few million years.

They are too far away to threaten Earth. If they do explode, they will simply paint the sky with light.

“A supernova blowing up that close will light up the sky,” Shull said. “It’ll be very, very bright but far enough away that it won’t be lethal.”

For now, the sun sits inside a protective zone. The surrounding clouds soften the worst radiation from space. They act like sheer curtains around a window, letting some light through but blocking much of the glare.

The shelter will not last. In time, the sun will drift beyond these clouds and into a harsher region. What that may mean for Earth is still unknown.

What is clear is that the story of Earth’s neighborhood is one of motion, chance, and enormous energy. Gates of radiation open and close as stars pass and die. Clouds drift and dissolve. Bubbles of hot gas expand and fade.

The universe has shaped Earth’s setting in quiet and violent ways. The evidence floats unseen just beyond the planets, written in charged atoms no one can touch.

Yet.

Research findings are available online in the Astrophysical Journal.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers reveal how passing stars and exploding giants shaped our early solar system appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.