Patients who depend on antibody drugs often spend long hours in infusion centers. These medicines are vital for treating many cancers, autoimmune disorders and infectious diseases, but current formulations usually require slow intravenous delivery. A typical dose may exceed 100 milliliters because most antibody drugs can only be dissolved at low levels.

“That volume is far too large for a subcutaneous shot, which usually holds less than 2 milliliters. When drug makers try to raise the concentration, the solution becomes so thick that it cannot pass through a standard needle,” said MIT chemical engineer Patrick Doyle to The Brighter Side of News.

Doyle’s MIT team including Talia Zheng, along with collaborators Lucas Attia and Janet Teng found a way around this barrier. They shifted antibodies from a dissolved state to tiny solid particles that still flow like a smooth liquid. Their findings, published in the scientific journal Advanced Materials, shows that antibodies can be packed at concentrations near 360 milligrams per milliliter, which is higher than what most companies can achieve in water.

Even at these levels, the mixture can pass through a 25-gauge needle with forces well below accepted limits. This approach could support antibody delivery in small volumes, opening the door to at-home administration for treatments that now require hours in a clinic.

Antibody drugs used today come as dilute water-based solutions. For many conditions, you need large doses, and current products cannot be concentrated enough to fit those doses into a small injection. When antibody levels climb above 200 milligrams per milliliter, the proteins begin to crowd together and interact. The solution becomes syrup-like, unstable and difficult to handle.

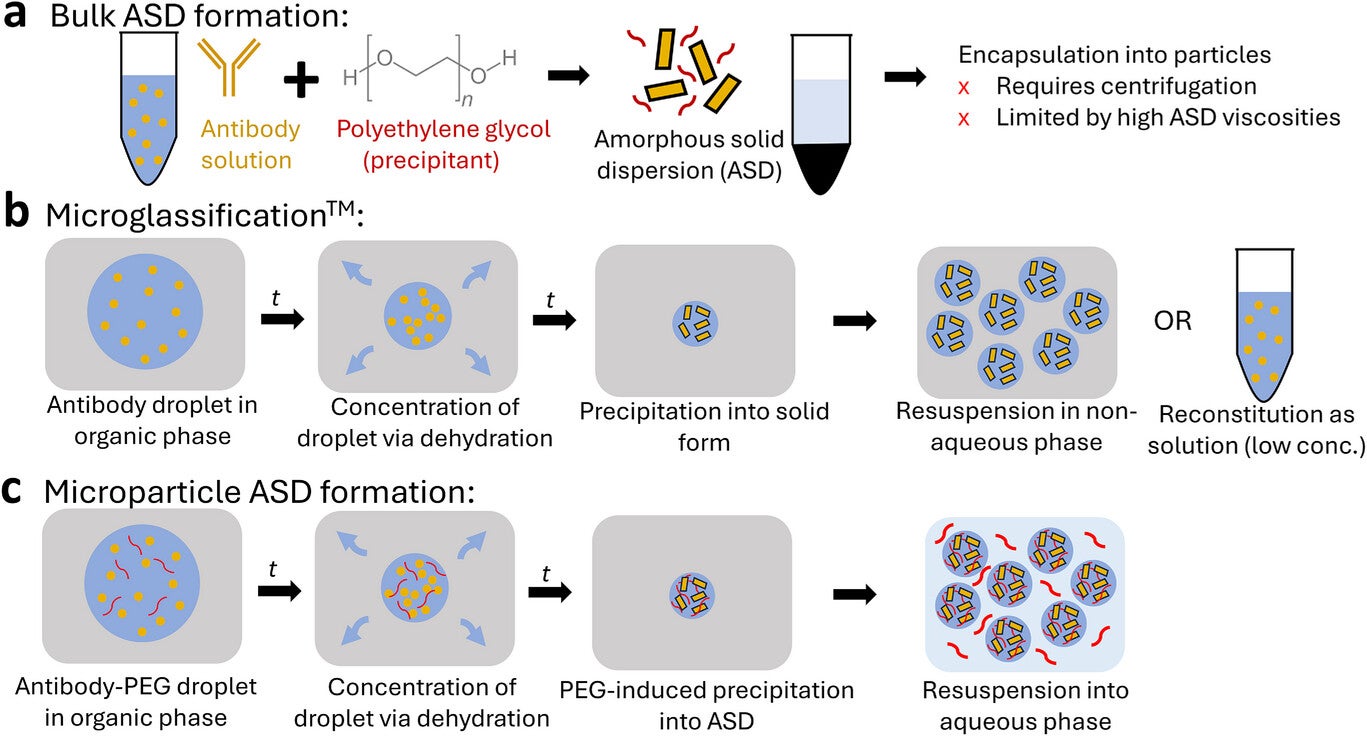

A few earlier studies showed that you could bypass this problem by shifting antibodies into solid particles and suspending them in a liquid, rather than keeping every molecule dissolved. One approach held the solids inside alginate hydrogel beads and relied on polyethylene glycol, or PEG, to help push the antibodies out of solution. This worked, but the particle production method depended on centrifugation. As a result, protein levels rarely rose above 300 milligrams per milliliter, and particle sizes often remained too large for smooth injection.

Some groups experimented with non-water solvents to achieve even higher loads. Those mixtures carried more drug, but they came with strong drawbacks that included pain at the injection site and added toxicity concerns. The ideal solution for patients and caregivers is a formulation that stays fully aqueous, holds a high dose and feels similar to common injectable medicines.

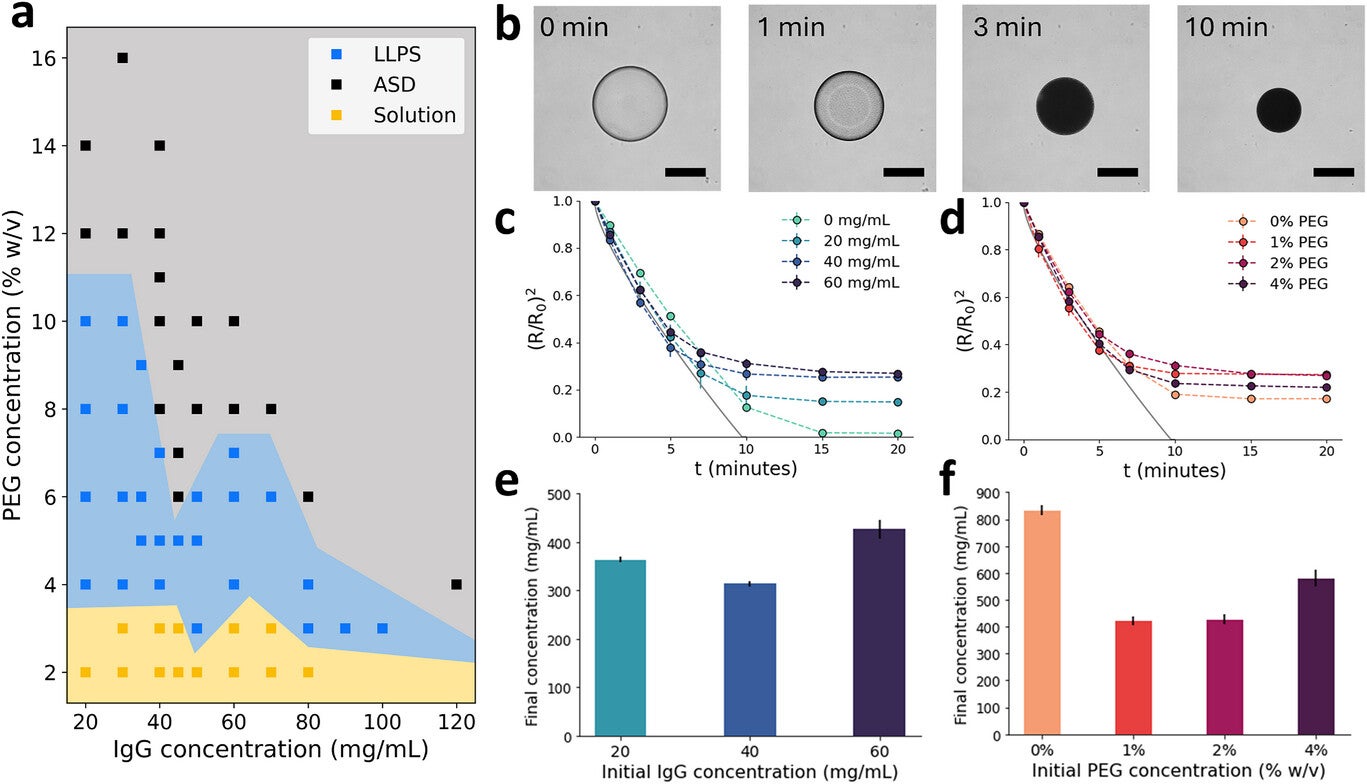

The new work builds upon how antibodies behave in the presence of PEG. At low PEG levels, antibodies remain dissolved. As PEG rises, the system separates into two liquid phases and eventually forms an amorphous solid when both PEG and antibody levels become high enough. Importantly, this solid form is reversible once PEG is diluted.

Researchers used this insight to design a dehydration process. They created droplets that held dissolved antibodies, PEG and alginate, then suspended the droplets in pentanol. Water moved out from each droplet into the surrounding pentanol, causing the antibody to cross the threshold where it formed a solid. In small tests, droplets containing 60 milligrams per milliliter antibody with 2 percent PEG shifted from clear to opaque within minutes. Calculations based on how much the droplets shrank showed that final antibody levels often landed between 300 and 600 milligrams per milliliter, and sometimes even higher.

Droplets that started at higher antibody or PEG levels created particles with more efficient packing. These early findings shaped the next step, which focused on making particles strong enough to handle injection forces.

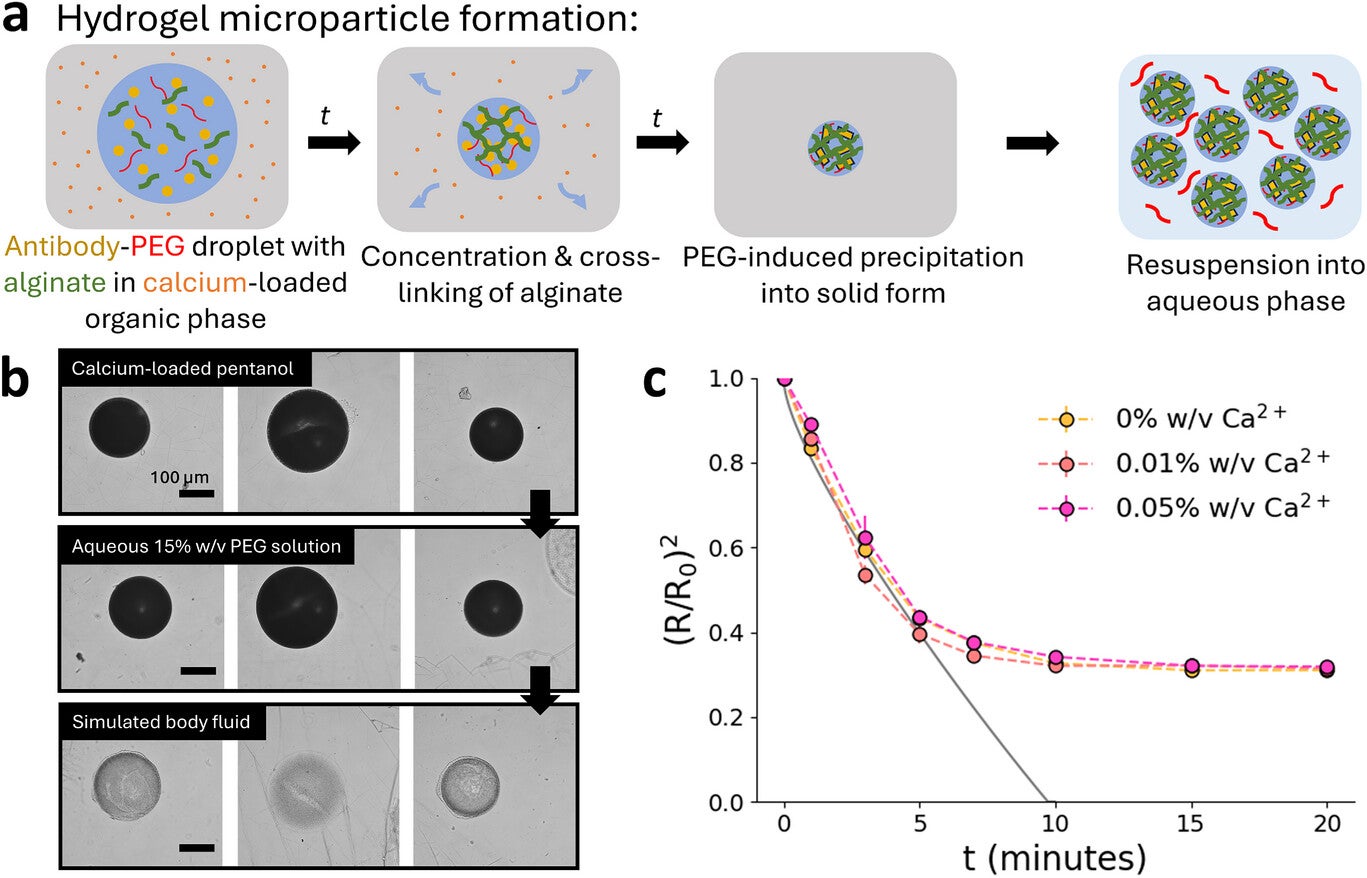

Solid particles formed by dehydration alone were fragile. To solve this, the team cross-linked alginate around the newly formed antibody solids. The alginate network created a soft hydrogel that held the antibody without changing its underlying behavior. When placed in aqueous PEG solution, the antibody remained inside the particles, ready to dissolve later inside the body once PEG levels dropped.

This process slightly increased particle size but not enough to limit use. More importantly, it supported very predictable loading and helped shield the antibody during storage. These features made the formulation suitable for larger production systems.

To move beyond single-droplet tests, the researchers built a microfluidic device that creates droplets at a steady rate. The antibody mixture enters at one junction, while pentanol containing calcium and surfactant flows across it. This forms droplets that dehydrate and cross-link downstream. By fine-tuning the flow rates, the team produced particles smaller than 100 micrometers, which is a key size target for subcutaneous injection.

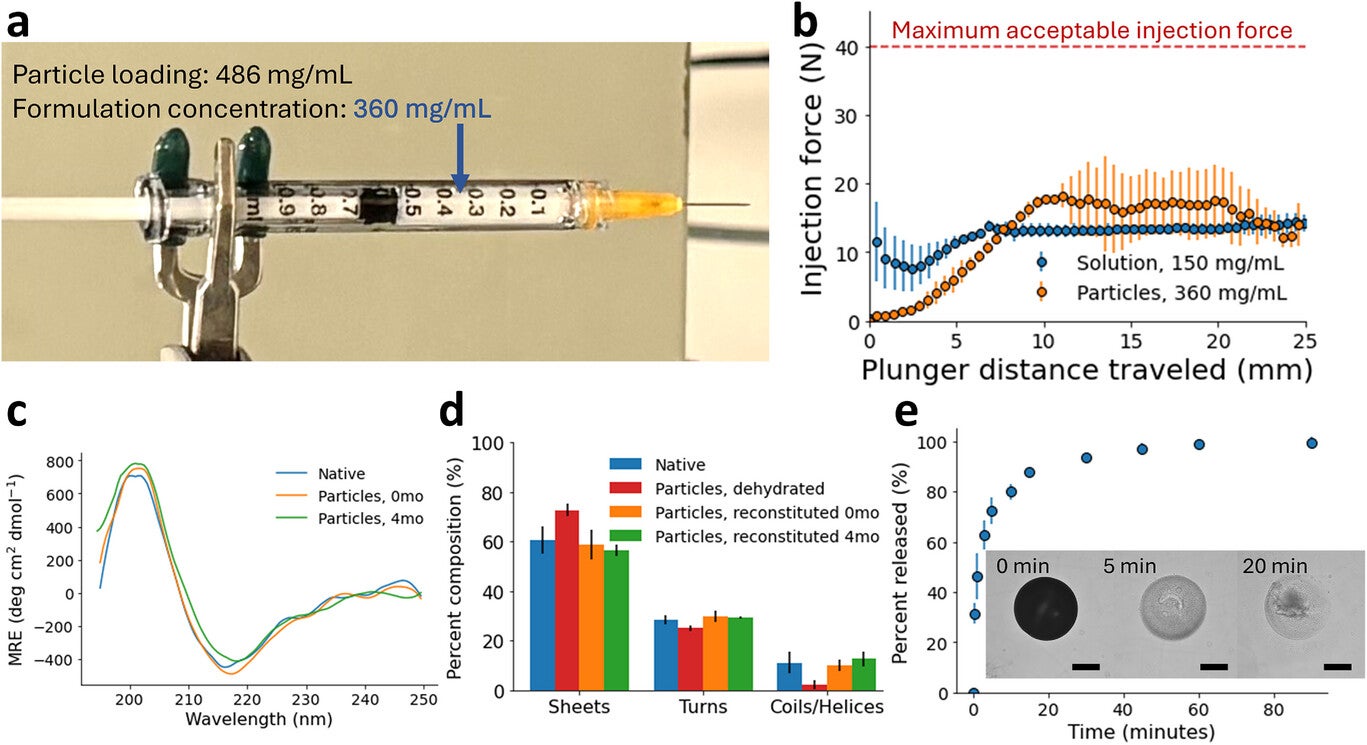

Particles near 105 micrometers carried heavy antibody loads. Starting with a solution of 60 milligrams per milliliter antibody and 2 percent PEG, the tiny hydrogel beads reached internal concentrations near 486 milligrams per milliliter. Encapsulation was nearly complete, with more than 98 percent of the antibody ending up inside the beads. When these particles were suspended in 10 percent PEG solution, the final formulation reached 360 milligrams per milliliter.

Injectability is central to patient comfort. Using a 1-milliliter syringe with a 25-gauge needle, the team found that forces during injection stayed between 10 and 20 newtons. Clinicians often set 40 newtons as the upper limit for acceptable force, so these results fall well within a safe range. The mixture offered similar resistance as a common antibody solution at 150 milligrams per milliliter, even though it carried more than twice the amount of drug.

Structural tests showed that the antibody kept its shape after dehydration and storage. Circular dichroism and infrared spectroscopy confirmed that secondary structure returned to normal when particles dissolved. An ELISA assay showed full bioactivity, and size-exclusion chromatography revealed that most of the antibody stayed as monomers. Release tests at body temperature suggested that more than 80 percent of the antibody becomes available within 10 minutes after injection.

“Together, these results outline a new way to pack a lot of antibody into a small, injectable dose while keeping the formulation aqueous, stable and easy to push through a standard needle,” Doyle told The Brighter Side of News.

This work points to a future where high-dose antibody drugs could be given as quick shots in a clinic or even at home. Shorter visits may reduce travel burdens, lower health care costs and improve access for people who struggle with repeated hospital trips.

The ability to store the particles for months adds flexibility for treatment centers and pharmacies. The new method uses a simple assembly process that can be scaled using existing production systems.

As next steps, the team plans to test the particles in animal models and explore larger manufacturing systems, which could speed progress toward clinical trials.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advanced Materials.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Antibody injections could replace slow IV drips in treating many diseases, MIT scientists find appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.