A classical nova may look simple at first. A faint star brightens, sometimes enough for you to spot without a telescope, then slowly dims over weeks or months. Behind that short burst of light sits a white dwarf in a tight orbit with a partner star. The white dwarf pulls in hydrogen from its neighbor until a runaway nuclear reaction ignites. The outer layer swells, and the system releases a wave of energy that should blow gas into space. That burst alone cannot explain why nova debris races outward at speeds that can reach 10,000 kilometers per second. Extra forces must be involved.

Ideas to explain this range from repeated waves of ejected gas to intense winds driven by ongoing nuclear burning. Some scientists even suggest that the companion star moves inside the swollen envelope for a brief period, adding its orbital energy to the blast. Understanding which idea is correct has taken on new urgency.

In the past decade, NASA’s Fermi Gamma Ray Space Telescope has detected high energy gamma rays from more than 20 novae. Those gamma rays point to shock waves within the ejecta where fast material slams into slower gas and boosts particles to extreme energies. In some cases, these shocks may be responsible for much of a nova’s light.

These discoveries have turned novae into powerful test cases for shock physics. Unlike distant supernovae or rare stellar mergers, novae evolve on human timescales. You can watch changes unfold over days and weeks instead of years. That makes nova outbursts valuable for studying how shocks shape some of the brightest events in the universe.

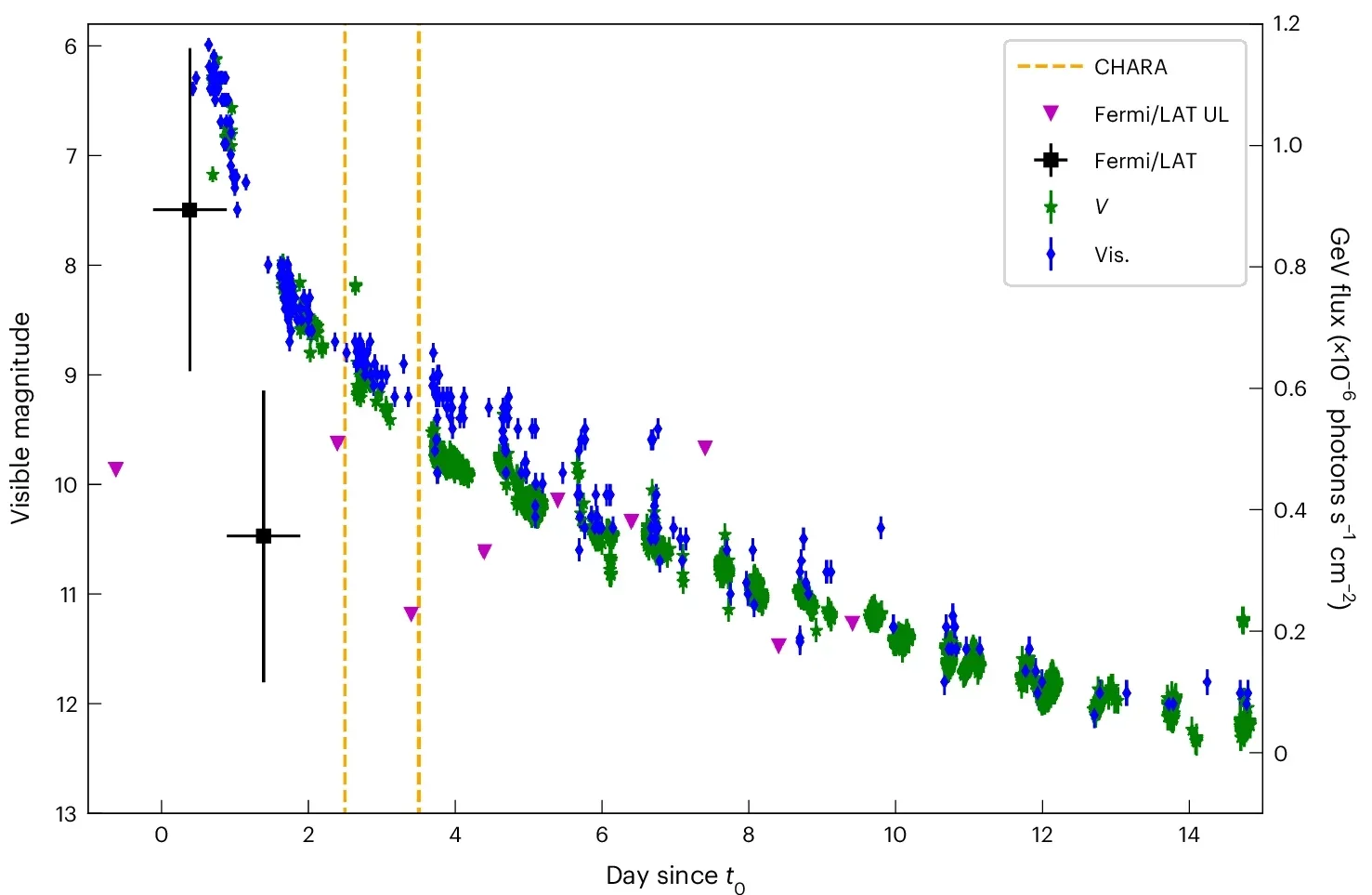

One of the most dramatic examples is V1674 Herculis, a nova that erupted in June 2021. It jumped from magnitude 8.5 to about magnitude 6.0 in less than a day. It then faded just as quickly. Fermi recorded gamma rays during the first two days, a sign that shock waves formed almost immediately. Within three days, astronomers used the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy Array, or CHARA, to take some of the earliest sharp images ever obtained of nova ejecta.

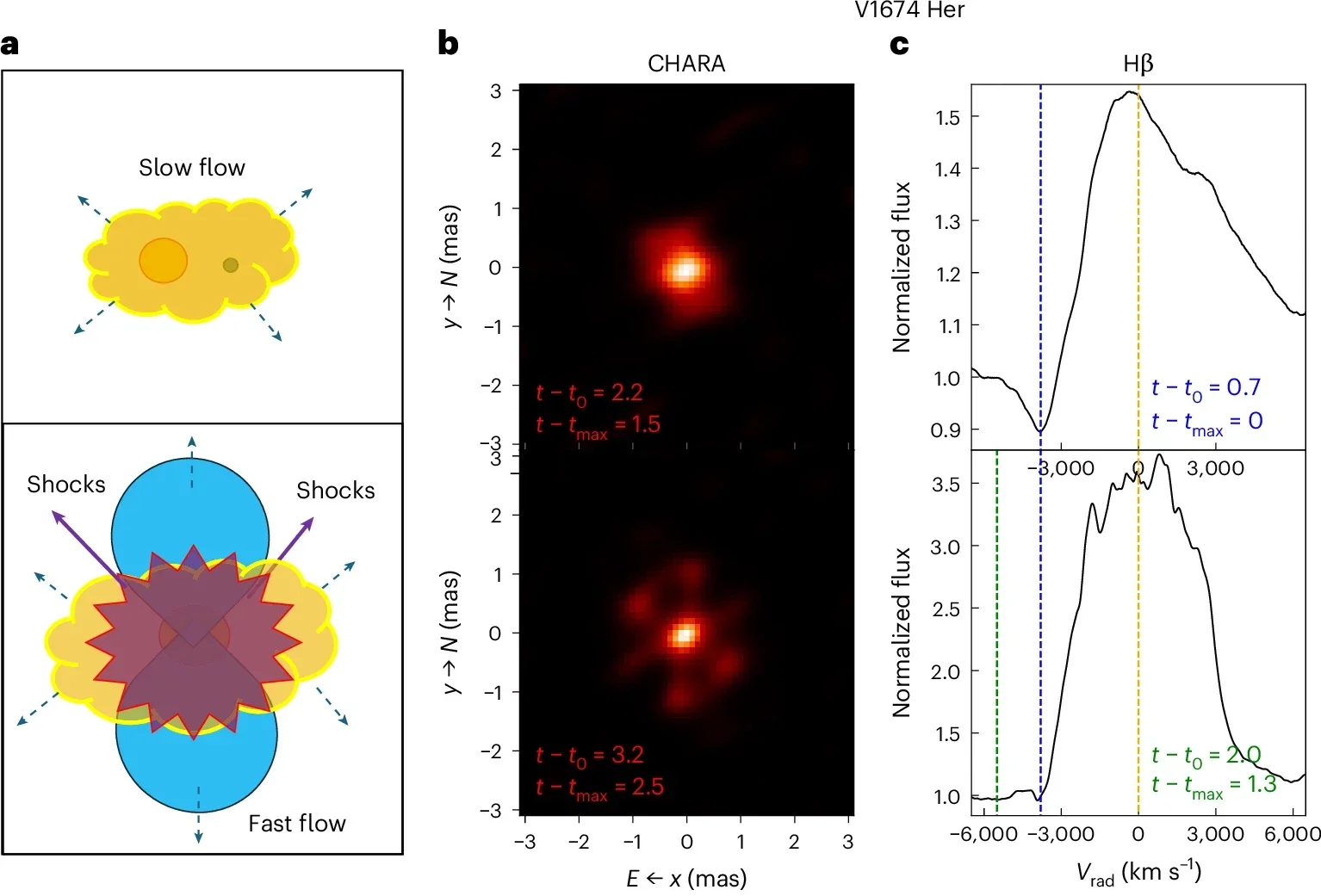

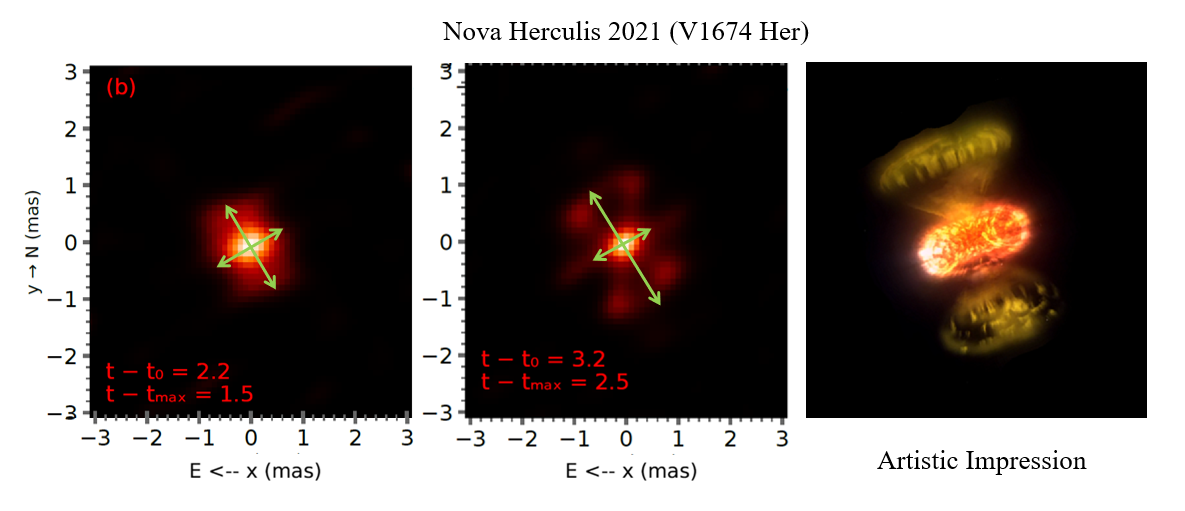

These images broke the old idea of a round fireball. They showed two separate outflows. One formed a bipolar structure that stretched in opposite directions. The other formed an elongated central region set at a different angle. The pattern matches a slower, dense outflow in the orbital plane followed by a faster wind escaping more freely above and below the system. Spectra taken during the same period confirmed two distinct speeds. When these flows collided, they created the strong shocks that lit up the gamma ray detectors.

The CHARA data allowed the group to measure the size of the fast outflow during its first days. When they combined those angular sizes with the speed measured from spectral lines, they estimated the nova’s distance. Their two measurements, taken just a day apart, pointed to a distance of about 6 kiloparsecs.

The agreement between the two results and with other methods supports the idea that CHARA was capturing the same fast component that produced the broad spectral features. The timing also matters. Spotting distinct shapes so early shows that the nova produced more than one ejection, and that these flows interacted from the start.

A very different story played out with another nova in 2021. V1405 Cassiopeiae rose slowly after it was first seen in March of that year. It held near the same brightness for about two weeks before climbing to a peak more than 50 days after discovery. Early spectra showed shallow absorption lines that pointed to a weak wind flowing from the system. The measured velocities dropped from about 1,500 kilometers per second to roughly 700 kilometers per second. That trend likely came from a decrease in opacity, not a real slowing of the gas.

Fermi did not detect gamma rays from V1405 Cas until more than two months after the eruption began. That delay hints that strong shocks formed much later than in V1674 Her. The long slow rise of the light curve and a string of flares over 200 days suggested repeated bursts of mass loss.

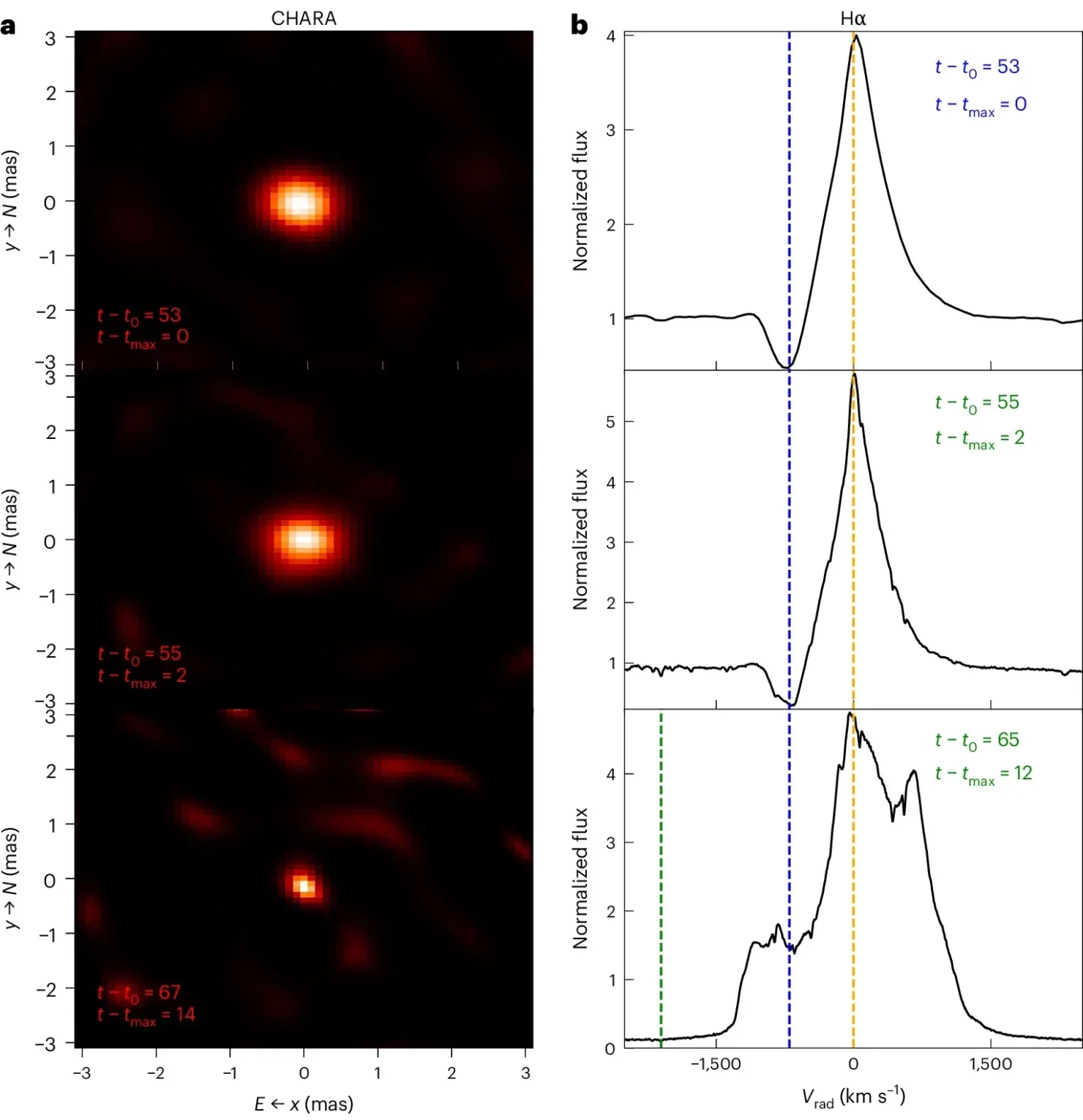

During this period, astronomers again used CHARA to probe the nova’s structure. On days 53 and 55 after discovery, nearly all the infrared light came from a compact central region about 0.85 astronomical units in radius. If the envelope had been expelled at the start with the speeds seen in the spectra, it should have grown to several dozen astronomical units by this time. CHARA would have easily picked up such an extended structure. Instead, most of the material stayed near the binary system for many weeks.

By day 67, the scene had shifted. The central region supplied only about half of the light. The rest came from an extended structure that CHARA resolved but could not map in detail. Around the same time, spectra revealed a broad emission component with a width that suggested speeds near 2,100 kilometers per second, while Fermi picked up gamma rays and the Swift X ray Telescope detected hard X rays from hot shocked gas. These signals suggest that faster material finally punched through the swollen envelope and created new shocks as it escaped.

Across the long decline of V1405 Cas, each bright flare and new spectral feature added to the evidence that the eruption released gas in multiple rounds. Some flows were slow and dense. Others were fast and thin. When the fast outflows caught up to earlier material, they produced fresh shocks that enriched the nova’s light with high energy radiation.

According to Texas Tech University researcher Elias Aydi, this detailed view challenges the long held belief that novae eject their envelopes in a single burst. Instead, they show layered eruptions shaped by the interplay of wind, gravity and orbital motion.

The group used interferometry at CHARA, which combines light from several telescopes to achieve sharp resolution. This method, also used to help image the black hole at the center of the Milky Way, made it possible to see nova structures while they were still developing. Aydi noted that this approach turns novae into real time experiments. Instead of a single flash of light, you watch an eruption unfold in rich detail.

In follow-up discussion with The Brighter Side of News, Aydi also said, “Scientifically, these results change how we understand nova explosions by directly revealing their geometry, timing, and shock formation at the earliest stages. This provides a critical benchmark for theoretical models and helps explain how such explosions produce high-energy radiation, including gamma rays.”

“More broadly, the research contributes to our understanding of how elements are processed and redistributed in the galaxy. For the public, it demonstrates how cutting-edge technology can be used to observe violent cosmic events in unprecedented detail, inspiring future scientists and engineers and highlighting the value of fundamental research,” he concluded.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New images reveal an early-stage stellar eruption (nova) in stunning detail appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.