Age checks no longer stop at store counters or ticket booths. They now shape access to social media, online games, streaming services, and regulated products such as alcohol, tobacco, and gambling. In digital spaces, confirming whether someone is a minor or an adult has become a daily challenge. The goal sounds simple, but the reality is complex. Systems must work quickly, resist fraud, and protect privacy at the same time.

For decades, age verification relied on government IDs and official databases. These methods remain common, but they bring risks online. Documents can be forged, and sharing personal records raises serious privacy concerns. After the COVID-19 pandemic pushed more services online, the demand for faster and safer age checks grew sharply. That shift has driven interest in biometric methods that estimate age from physical or behavioral traits rather than paperwork.

Facial age estimation has led this trend. Some systems report accuracy above 95 percent when separating minors from adults. Other approaches have tested hand movements, fingerprints, voice patterns, and eye features, with mixed results. At the same time, governments and standards groups have stepped in. International efforts such as IEEE P2089.1 and the Global Age Assurance Standards Summit stress that age checks must protect children while limiting data collection.

Against this backdrop, a different signal has drawn attention. Instead of faces or fingerprints, researchers have begun looking at the heart. Electrical activity from the heart, recorded through an electrocardiogram or ECG, changes as people age. Those shifts may offer a new way to estimate age with less risk to personal identity.

An ECG records electrical signals that travel through the heart during each beat. Doctors use these signals to diagnose heart conditions by examining features such as wave timing and shape. Decades of clinical research show that these patterns evolve with age. Amplitude, duration, and rhythm vary across childhood, adulthood, and later life.

Early studies tried to reverse these changes to predict age. Researchers extracted specific ECG features and fed them into traditional statistical models. Results were modest. Most studies relied on small, similar patient groups and struggled to generalize beyond hospital settings.

Deep learning later transformed the field. Neural networks can learn patterns directly from raw ECG signals, without hand-crafted features. Large studies using hospital-grade 12-lead ECGs have predicted age with errors under seven years. Some introduced the idea of “delta age,” the gap between predicted and actual age, which links closely to heart disease risk.

Yet these advances came with limits. Clinical ECG systems require multiple electrodes and trained staff. They are not practical for everyday use or rapid online checks. Meanwhile, smartwatches already record single-lead ECGs from the wrist and have proven useful for user identification. Until recently, their potential for age estimation remained largely unexplored.

“We collected first-hand ECG data using a Fitbit Sense smartwatch and tested how well it could be used to estimate age. In all, we gathered signals from 220 individuals between June 2023 and April 2025. All participants reported being healthy with no significant cardiac history, and the work was approved by Concordia University’s ethics board, with additional authorization to collect data from minors in Montreal schools,” Azfar Adib from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Concordia University, told The Brighter Side of News.

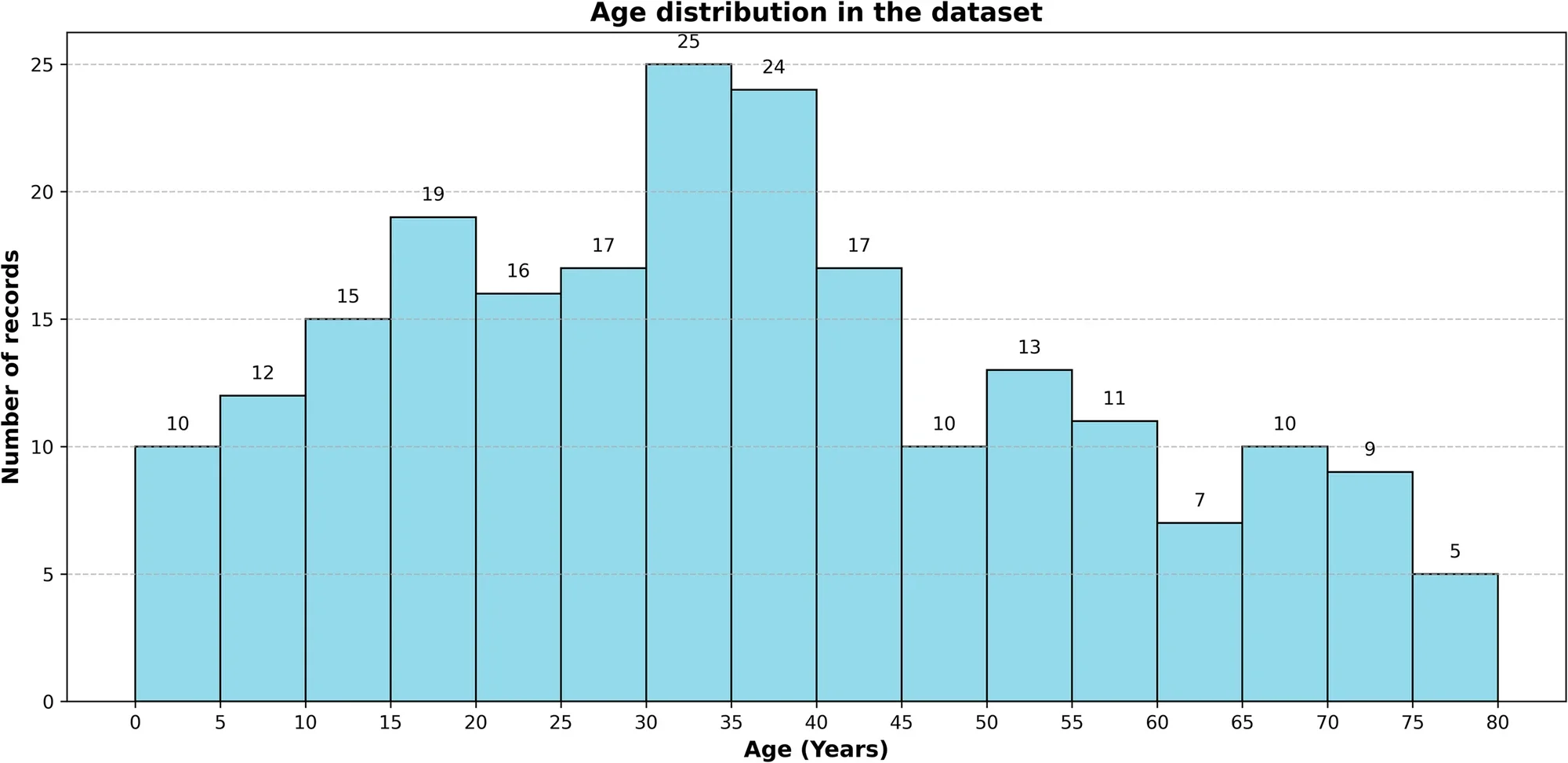

“The dataset covered a wide age range, from 3 to 78 years old, with most participants clustered in the 30–40-year range. Of the 220 participants, 133 were male and 87 were female. Each record consisted of 2,800 samples from a 30-second ECG recording captured at 250 Hz. Alongside the ECG, researchers also recorded each person’s gender and cardiac health history,” he continued.

The team first examined heart rate variability, a measure often linked to aging. In theory, variability declines as people get older. In practice, the smartwatch data showed no clear trend. Individual differences blurred the picture. This finding suggested that simple statistics would not be enough. More flexible models were needed.

The researchers tested several machine learning approaches. These included a feedforward neural network, long short-term memory networks, an Inception1D model, and a transformer-based model. They also compared different inputs, ranging from raw de-noised ECG signals to frequency and wavelet features. Performance was measured using mean absolute error.

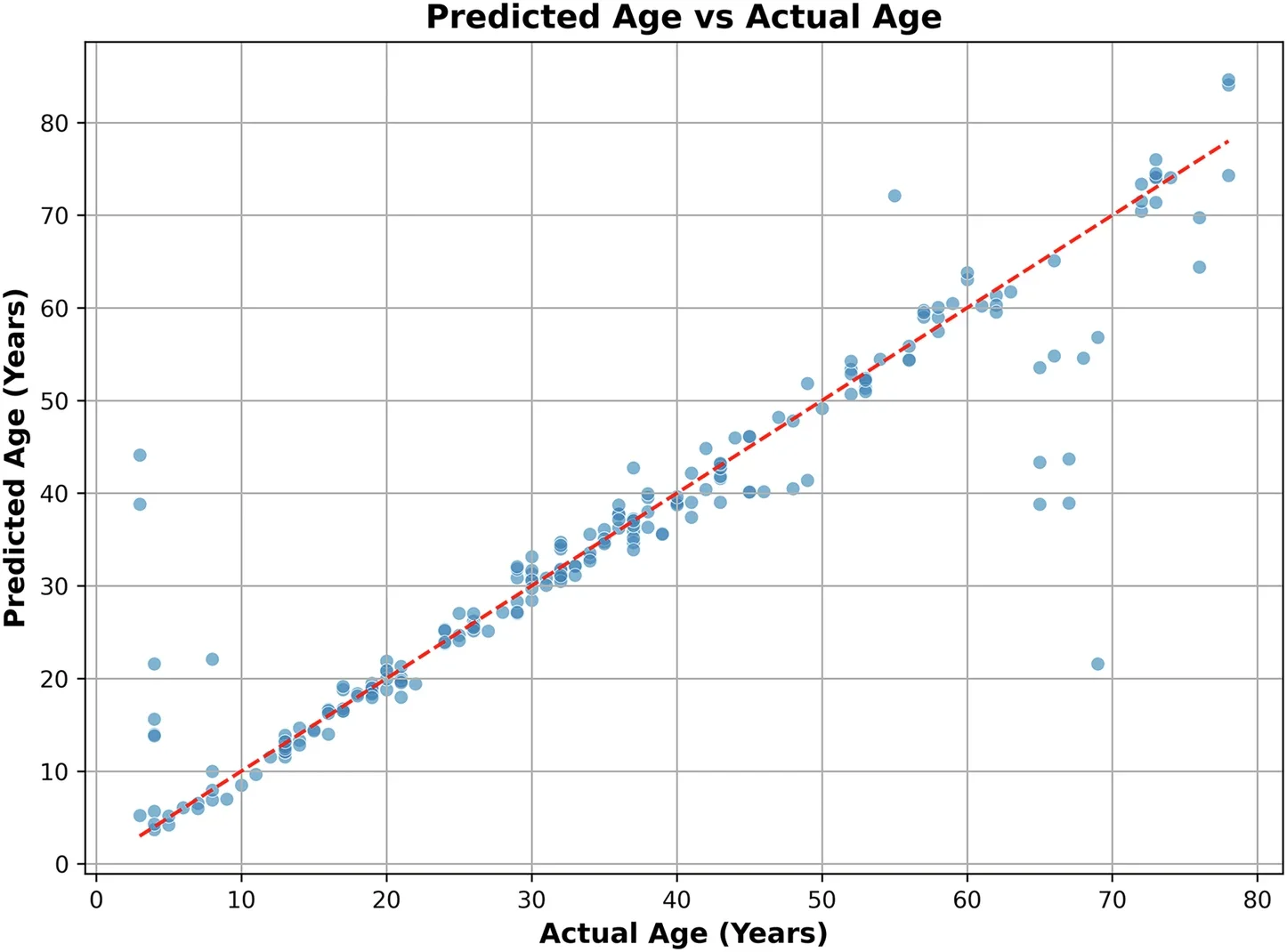

The simplest method delivered the strongest result. A feedforward neural network applied directly to the de-noised ECG signal predicted age with an average error of 2.93 years. More complex models performed similarly but did not improve accuracy. Adding extra features also failed to help.

The team also tested a transformer model with self-attention and residual connections. Transformers often excel with large datasets, but here they struggled. They trained slowly, required more computing power, and did not beat the simpler network.

Saliency maps showed why the feedforward network worked. The model focused on physiologically meaningful regions of the ECG, including the QRS complex and R-peaks. These areas are known to change with age, which helped validate the approach.

Performance varied across age groups. The model worked best for adolescents and young adults, especially ages 11 to 20. Accuracy dropped for very young children and older adults. This pattern matches known heart development trends. Changes occur rapidly early in life and slow later on.

Gender differences were small. The mean error was 2.85 years for males and 3.06 years for females. These results suggest broadly consistent performance.

Beyond exact age prediction, the study tested practical thresholds. The team ran classification tasks around ages 12 and 21. Across models, results showed strong potential to separate minors from adults using smartwatch ECG data alone. Reported accuracy ranged from 93 to 96 percent.

Compared with facial analysis, ECG-based age estimation offers key privacy benefits. Heart signals are difficult to fake and less tied to visible identity. Processing can occur on a device, reducing the need to send images to servers. ECG data also avoids bias linked to skin tone.

There are trade-offs. Heart conditions can affect signals, while facial systems often avoid that issue. Facial methods also benefit from massive image datasets. ECG research is still catching up.

The Fitbit Sense hardware can handle basic ECG processing in real time, with delays under 100 milliseconds. More demanding models usually run on a paired phone or cloud system. A 30-second ECG recording uses about 1 to 2 percent of the battery. Frequent use can shorten battery life by a few days.

Data security remains central. ECG data travels via encrypted Bluetooth and is stored with end-to-end encryption. Fitbit de-identifies research data under GDPR and HIPAA rules. Users control when recordings start and can delete or export their data.

Corresponding author, Azfar Adib from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Concordia University, told The Brighter Side of News

Research findings are available online in the journal npj Biomedical Innovations.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Smartwatch heart signals may offer an accurate and safe way to verify age online appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.