Earth’s inner core has long puzzled scientists because seismic waves move through it unevenly. Compressional waves from earthquakes travel about 3 to 4 percent faster along the planet’s rotation axis than across the equator. That difference, known as seismic anisotropy, changes with depth.

The outer part of the inner core shows weaker anisotropy, around 2 percent or less, while the central region appears far more directional, reaching 4 to 6 percent. Explaining why this pattern shifts with depth has remained a central challenge in Earth science.

Researchers have proposed two main explanations. One suggests that grains or inclusions inside the core line up by shape, a process called shape preferred orientation. The other focuses on lattice preferred orientation, where crystal lattices themselves align as the material deforms.

Shape alignment would require liquid pockets trapped inside the solid inner core. Most evidence suggests those liquids would be squeezed out over time, making that option unlikely. That leaves lattice alignment, driven either by how iron alloys freeze or how they slowly deform under extreme stress.

The inner core is thought to be mostly iron with some nickel, arranged in a hexagonal close packed structure. Seismic data, however, show that it is less dense than pure iron. That gap implies the presence of lighter elements. Scientists have pointed to silicon, carbon, oxygen, sulfur, and hydrogen as likely contributors, with more than one present at once.

Previous studies suggested that iron mixed with silicon or carbon could match the core’s density and sound speeds. Theory also predicted that single crystals of hexagonal iron could show strong elastic anisotropy under core conditions. Experiments confirmed that this form of iron is relatively weak and easy to deform, which helps crystals align. Still, most earlier work focused on pure iron or iron mixed with one element. How silicon and carbon together affect iron remained unclear.

To address that gap, an international team led by scientists from the University of Münster studied an iron alloy containing both elements. The alloy included 2 percent silicon and 0.4 percent carbon by weight. This composition resembles models proposed for the inner core.

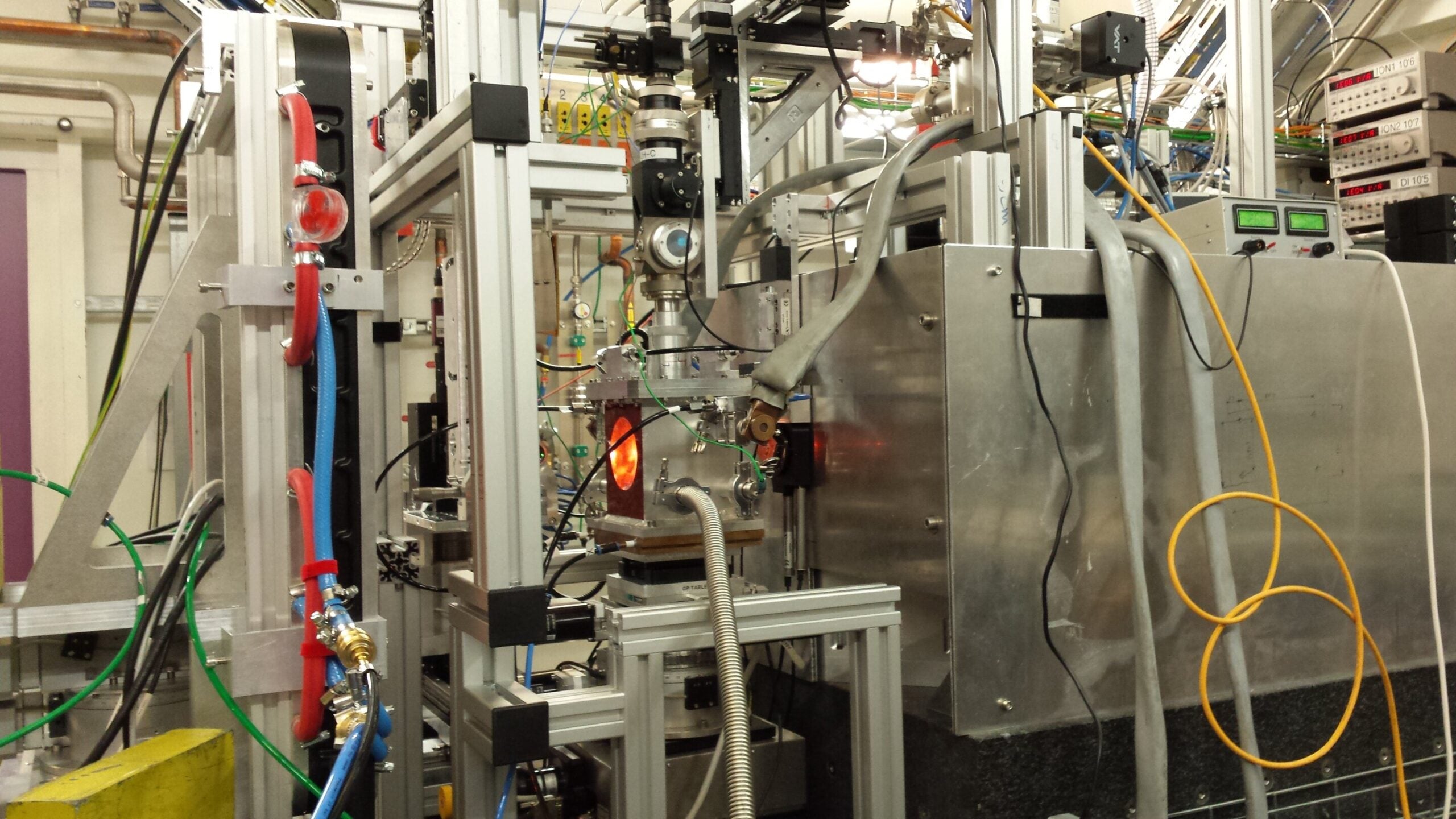

Using diamond anvil cells, the researchers compressed and heated the alloy to pressures up to 128 gigapascals and temperatures up to 1100 kelvin. These conditions approach those deep inside Earth. The experiments took place at the PETRA III light source at Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron in Hamburg, using advanced X ray diffraction methods. The findings were published in Nature Communications.

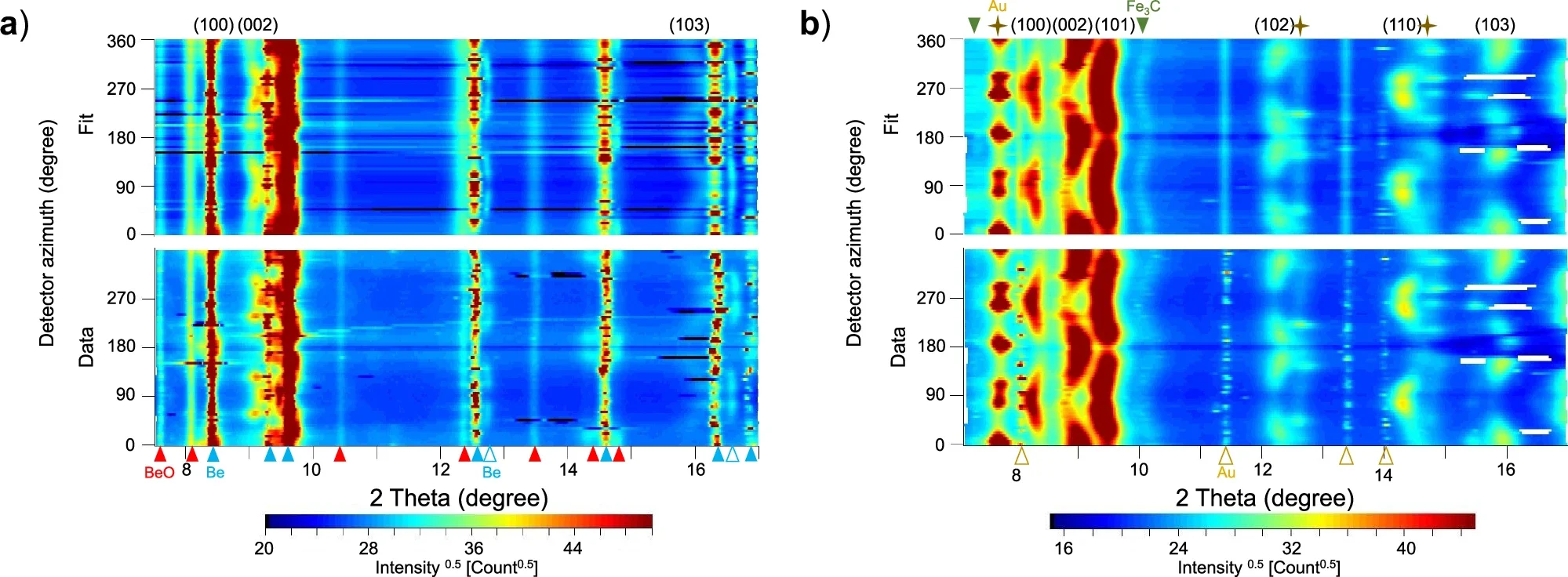

At low pressure, the alloy begins in a body centered cubic structure. As pressure rises above about 10 gigapascals, it starts to transform into a hexagonal structure. That transition completes near 27 gigapascals. When heated at higher pressure, a small amount briefly shifts into a face centered cubic form, then disappears again as pressure increases further.

By tracking subtle changes in diffraction patterns, the team measured lattice strain, a marker of how crystals deform under stress. Up to about 60 gigapascals, strain values stayed nearly constant at both room temperature and high temperature. Beyond that point, strain increased slightly at lower temperature but dropped at higher temperature. New diffraction peaks showed that some carbon separated out to form iron carbide, reducing strain in the remaining alloy.

The researchers also measured how strain changed with temperature at constant pressure. From this, they calculated a temperature coefficient that improved on earlier estimates. This step mattered because it allowed more reliable extrapolation to the inner core.

Using established methods, the team converted lattice strain into yield strength. At room temperature, the alloy’s strength rose steadily with pressure, reaching about 15 gigapascals at the highest load. At high temperature, the alloy weakened, but it still remained stronger than pure iron and other iron alloys studied before.

The key difference was carbon. Compared with iron silicon alloys without carbon, the mixed alloy consistently showed higher strength. The researchers concluded that carbon significantly reinforces iron silicon alloys under extreme conditions.

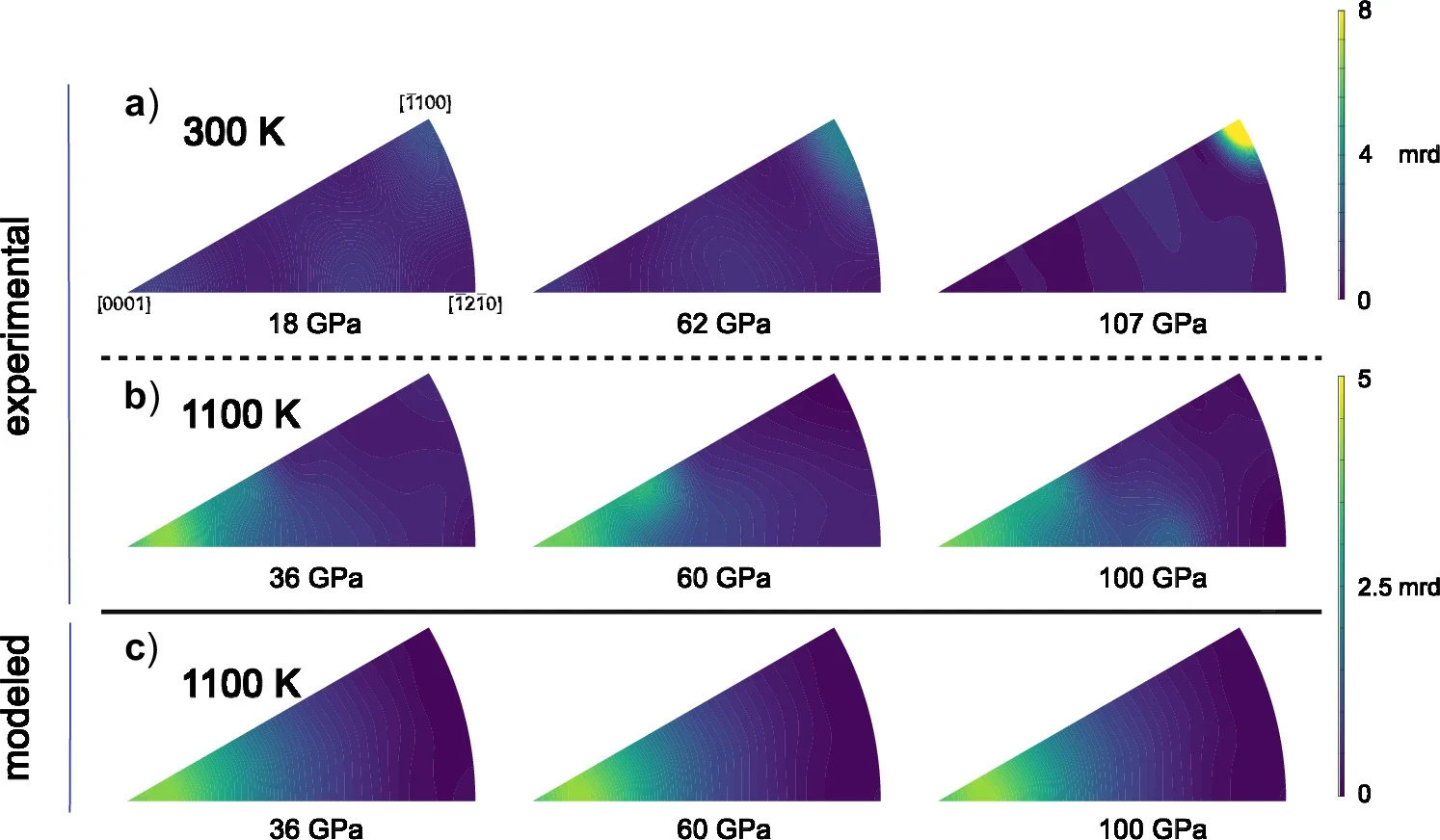

X ray images also revealed how crystals aligned during deformation. Texture was weak at first but grew stronger as pressure increased. Different alignment directions dominated depending on pressure and temperature. To interpret these patterns, the team used elasto visco plastic self consistent modeling. The results showed that basal slip dominated deformation, but additional slip or twinning mechanisms were required to fully match the data.

With deformation mechanisms identified, the researchers extrapolated their measurements to true inner core pressures and temperatures. They calculated yield strength and viscosity for the alloy under those conditions. The estimated viscosities fell between 10¹⁴ and 10¹⁸ pascal seconds, a range consistent with geophysical constraints.

These values imply shear stresses of roughly 1,000 to 30,000 pascals in the inner core if this alloy dominates. Thermal convection models predict similar stress levels. That means convection alone could deform this material enough to produce lattice alignment and seismic anisotropy.

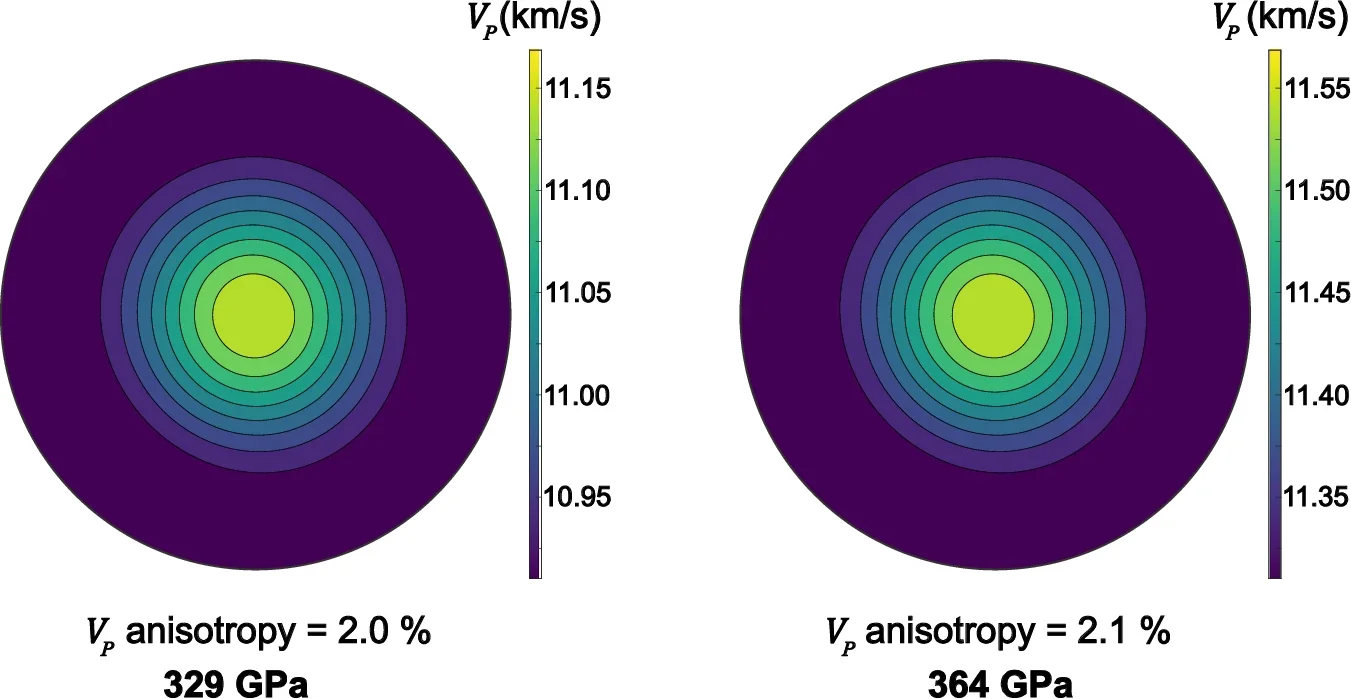

The team then calculated how these textures affect compressional wave speeds. At room temperature, anisotropy remained below 1 percent. At high temperature and when extrapolated to the inner core, anisotropy reached about 2 percent. That matches seismic estimates for the outer part of the inner core but falls short of the stronger signal seen at the center.

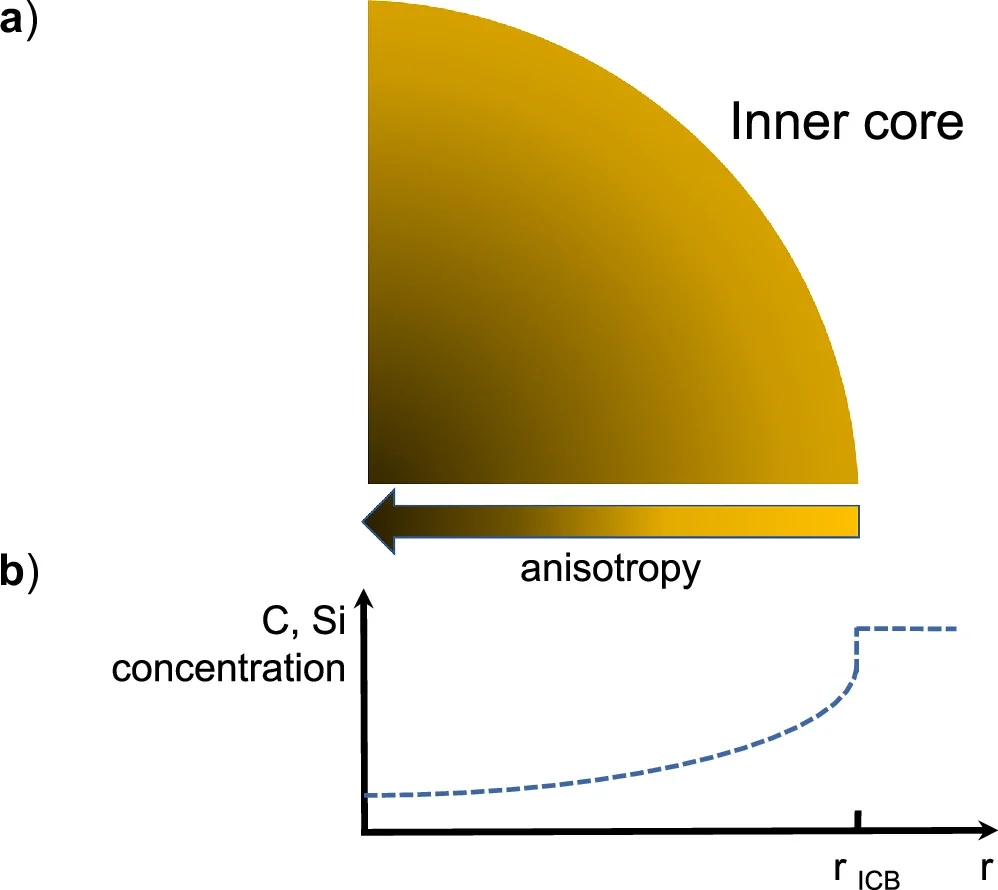

Prof. Carmen Sanchez-Valle of the University of Münster explained to The Brighter Side of News, “Our study proposes chemical stratification of silicon and carbon within the inner core. As the core first begins to crystallize at its center and solidification moves outward along the temperature gradient, the earliest solids near the center are expected to form on the iron-rich side of the eutectic as hcp iron solid solution.”

“As temperature drops, the concentrations of silicon and carbon in the solid increase. At the same time, pressure decreases from the center toward the inner core boundary, shifting eutectic compositions to higher light-element contents. Both effects favor higher silicon and carbon concentrations in the outer parts of the inner core,” she continued.

To explain this difference, the researchers proposed chemical layering. As the inner core began to crystallize at its center, early solids likely formed with less silicon and carbon. As solidification moved outward and temperatures dropped, the solid incorporated more of these light elements. Pressure also decreases toward the inner core boundary, favoring higher light element content.

In this view, the central region remains closer to pure iron and develops strong anisotropy. Outer layers become richer in silicon and carbon and show weaker anisotropy. “There have been several hypotheses for the origin of these anisotropies,” said Sanchez-Valle. “Unfortunately, there are very little experimental data on how such LPO might look like in Earth’s iron core.”

By combining experiments and modeling, the new work links seismic patterns to chemical stratification rather than changes in deformation style alone. “This matches the different anisotropies of velocities observed in the seismic profiles,” said team leader Ilya Kupenko.

Understanding the inner core’s structure helps scientists refine models of Earth’s thermal history, magnetic field generation, and long term evolution.

By tying seismic signals to chemistry, the study offers a clearer picture of how Earth formed and cooled. It also improves predictions of how the core may change over billions of years, which affects the stability of the magnetic field that shields life at the surface.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Silicon and carbon in iron may explain the onion-like layering of Earth’s inner core appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.