Understanding how galaxies grow has long stood as one of astronomy’s core challenges. Over time, scientists have gathered evidence that galaxy mergers matter. When two galaxies move close, gravity can pull gas toward their centers. That gas can spark new stars and feed a supermassive black hole, switching it on as an active galactic nucleus, or AGN. Still, researchers have debated how strong this link truly is.

New findings from the European Space Agency’s Euclid mission now sharpen that picture. Using the mission’s first quick-release data, scientists combined detailed imaging, multi-wavelength observations, and artificial intelligence to track mergers and black hole activity across billions of years. Their analysis shows that mergers strongly increase the odds of AGN activity, especially for the most powerful black holes, while quieter systems often follow different paths.

Past studies have reached mixed conclusions. Many simulations suggest mergers push gas inward, fueling black holes. Some observations back this up, finding more AGN in merging galaxies. Other work argues most AGN turn on through calmer internal processes, without major collisions.

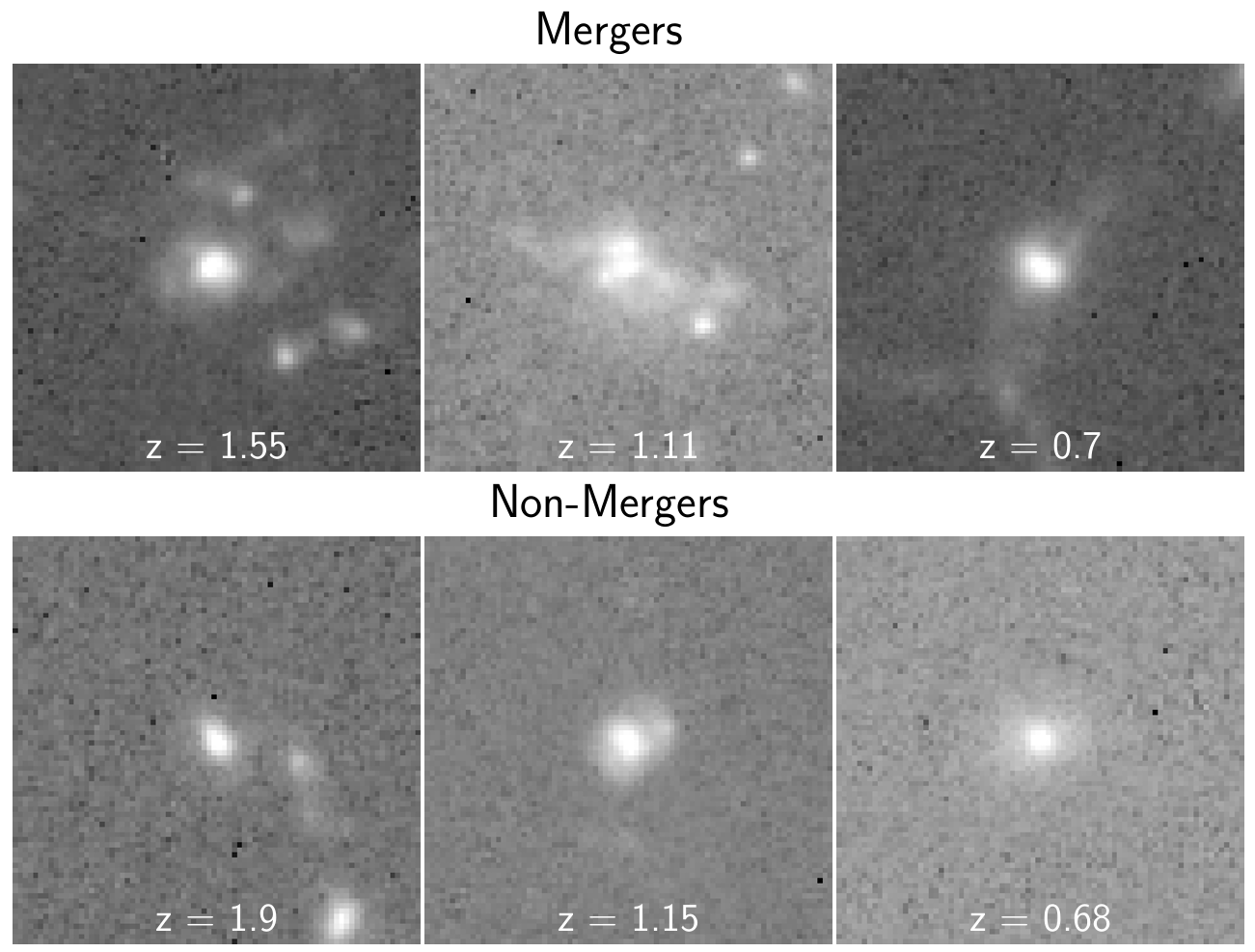

Part of the disagreement comes from how hard mergers and AGN are to spot. Astronomers can identify mergers by eye, by distorted shapes, or by close galaxy pairs. AGN are even trickier. Some glow in X-rays, others show bright optical lines, radio waves, infrared colors, or changes in brightness. Each method finds different types of AGN.

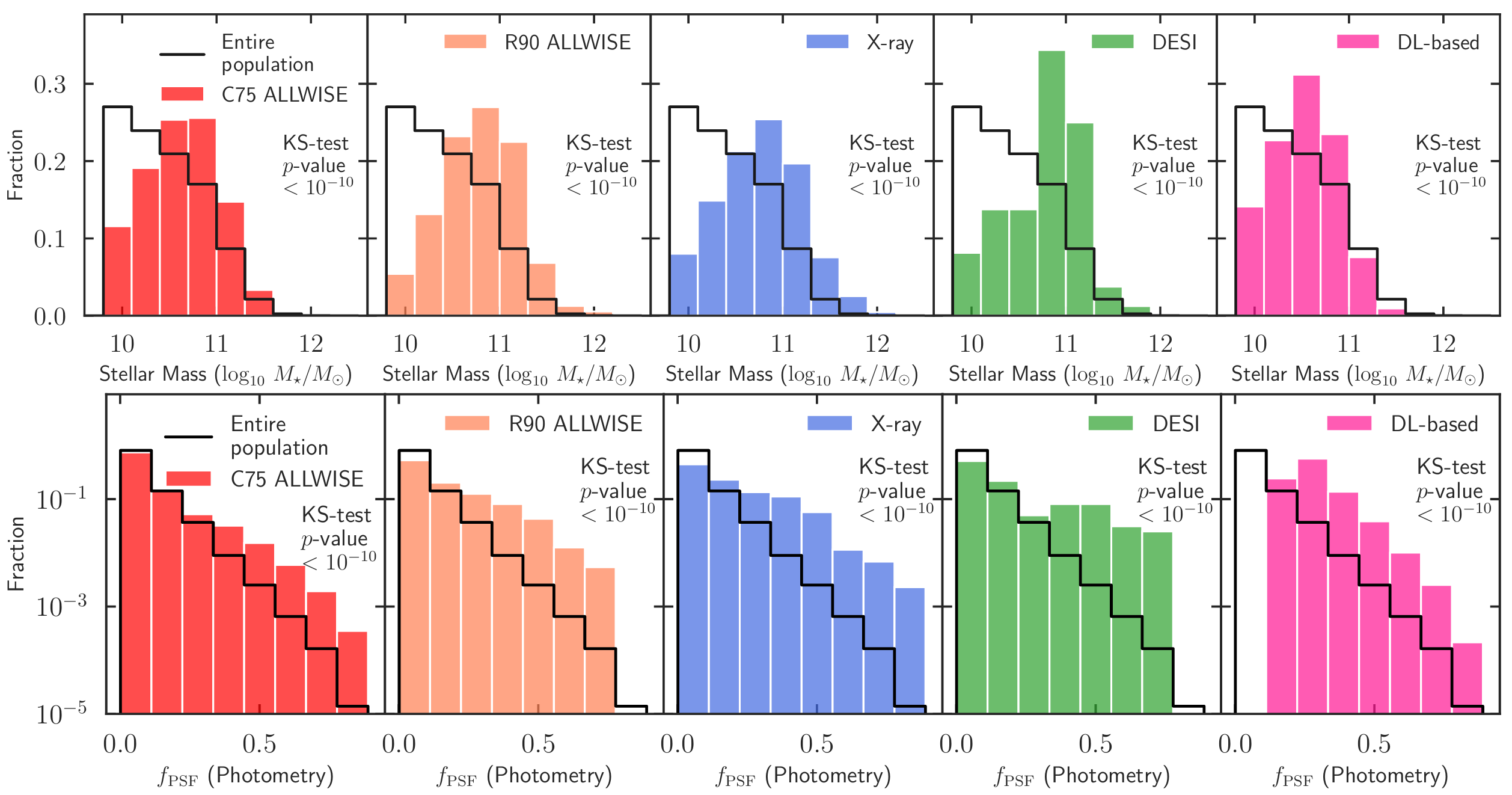

The Euclid study tackled this problem by casting a wide net. The team combined X-ray surveys, optical data from the DESI project, mid-infrared observations from WISE, and a deep-learning method that flags bright central point sources in Euclid images. This approach captured both exposed AGN and those hidden by dust.

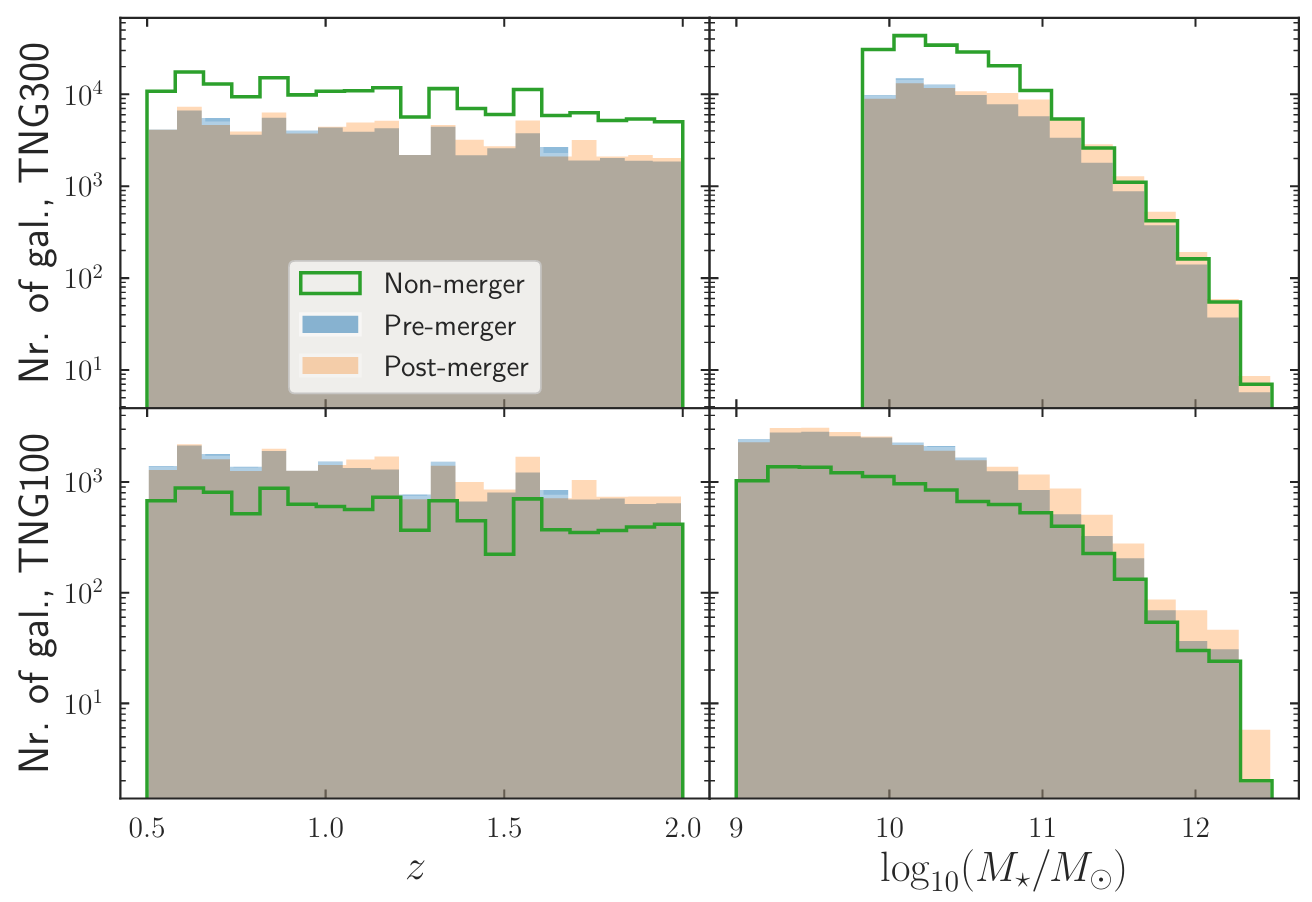

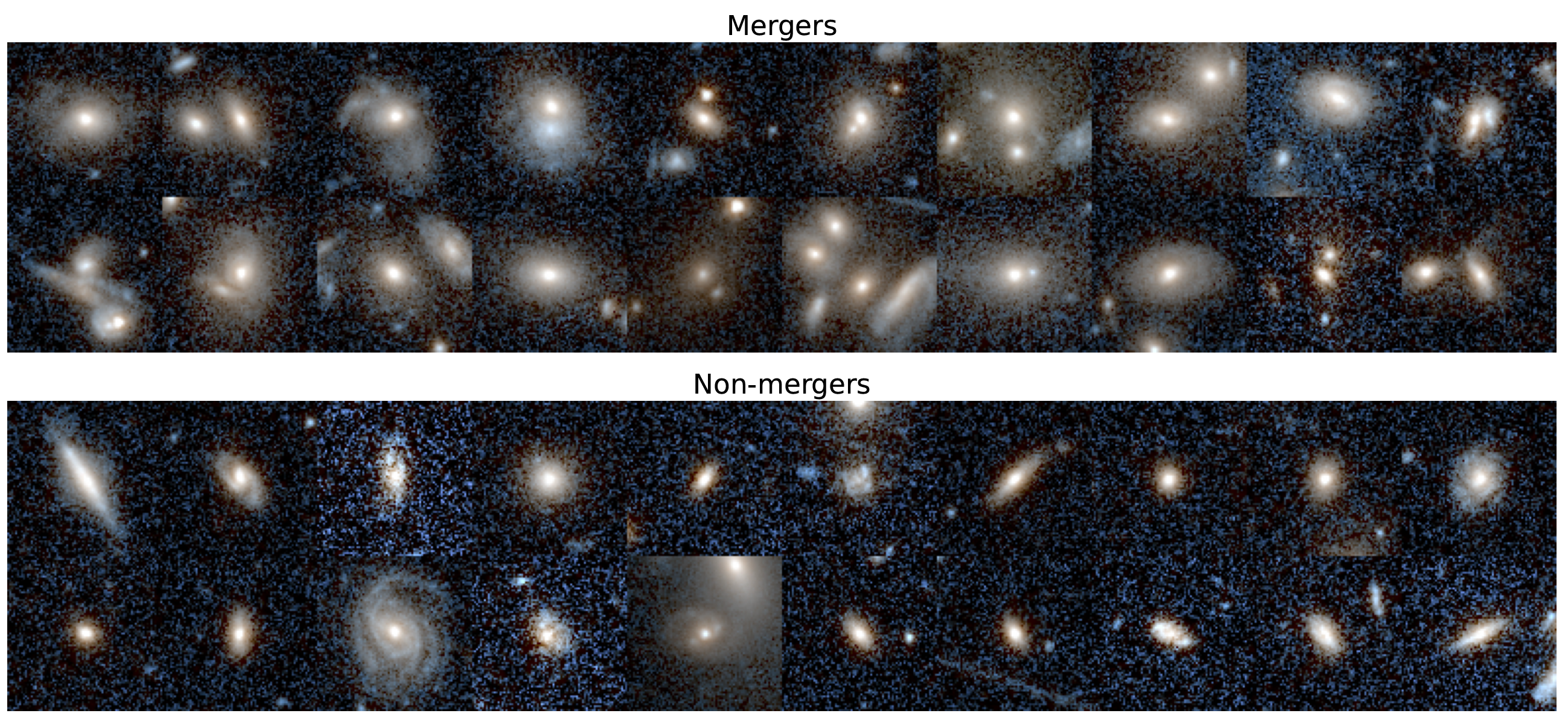

To identify mergers, researchers trained a neural network using mock Euclid images created from IllustrisTNG cosmological simulations. These simulated galaxies included full merger histories. By placing them into real Euclid backgrounds, the team taught the model to spot major mergers reliably. They then applied it to more than 350,000 galaxies with well-measured masses, spanning redshifts from 0.5 to 2.

The first question was simple. Are AGN more common in mergers? Across every AGN type tested, the answer was yes.

X-ray AGN appeared about twice as often in merging galaxies as in similar isolated ones. Optical AGN identified by DESI were three to four times more common in mergers. Mid-infrared AGN selected with strict color criteria showed an excess of about four. Even AGN flagged by deep learning in Euclid images appeared roughly three times more often in mergers.

These patterns held across two cosmic eras, from redshift 0.5 to 0.9 and from 0.9 to 2. This shows that, even as the universe changed, mergers remained an effective way to activate black holes.

The team also flipped the question. Among galaxies hosting AGN, how many were mergers? For X-ray, optical, and mid-infrared AGN, between 40% and 65% lived in merging systems. That rate was about twice as high as in galaxies without AGN.

To dig deeper, the researchers examined how merger rates change as AGN grow stronger. One key measure was the fraction of light coming from a galaxy’s unresolved central point source. This reflects how much the AGN outshines its host.

The merger fraction rose steadily as this point-source fraction increased, peaking near 70% when the AGN strongly dominated the galaxy’s light. Beyond that point, the merger fraction dropped. Tests showed this decline was not simply because bright AGN hide merger features. Instead, it likely reflects AGN that look dominant only because their host galaxies are faint, not because the black holes are extremely powerful.

When AGN power was measured directly, the trend became clearer. Mergers grew more common as AGN luminosity increased. At lower redshift, mergers dominated once AGN reached about 10^43.5 erg per second. At higher redshift, where galaxies held more gas, mergers became dominant only above about 10^45 erg per second.

For the brightest AGN, above 10^45 to 10^46 erg per second, mergers were by far the most common hosts. This matches earlier studies of luminous quasars.

Because artificial intelligence played a central role, the team tested how errors might affect the results. They ran thousands of simulations that added realistic misclassifications based on the model’s accuracy. The main conclusions held each time. AGN remained more common in mergers, and merger rates still climbed with AGN power.

They also checked for biases from galaxy mass and unclassified objects. Again, the core results stayed the same.

“Machine-learning classifications always bring concerns about accuracy,” University of British Columbia researcher Dr. Allison Man shared with The Brighter Side of News. “Our team addressed this by running extensive simulations that injected realistic levels of misclassification based on the measured precision and recall of their merger classifier. We found that across 1,000 trials, the major conclusions held: AGN remained more common in mergers, and merger fractions still rose with AGN power. The exact values shifted slightly, but the overall trends stayed intact,” she continued.

“We also checked whether unclassified galaxies or differences in galaxy mass could bias results. In both cases, our main conclusions remained unchanged,” she added.

This early look at Euclid data offers the clearest multi-wavelength view yet of how galaxy mergers and AGN connect. The findings show that mergers reliably raise the chances of AGN activity across all types. Major mergers play a key role in powering the brightest black holes. Dusty AGN show the strongest link to mergers, suggesting gas and dust funnel inward during collisions. At earlier times, mergers mattered less for bright AGN, likely because young galaxies held more fuel.

Using AI, the research team analyzed hundreds of thousands of mergers from up to 10 billion years ago. They found AGN were two to six times more common in merging galaxies than in non-merging ones.

“We’re starting to explore just how supermassive black holes form and evolve, and to pin down the connection between galaxy mergers, supermassive black hole mergers and how they contribute to building up the most massive black holes in the universe,” Man said.

As Euclid continues its mission, it will image billions of galaxies in greater detail. Those data should help trace how mergers and black holes shaped the universe during its most active years.

By clarifying how and when galaxy mergers trigger black hole growth, this research helps refine models of galaxy evolution. It shows when violent collisions matter most and when calmer processes can do the job.

These insights will guide future surveys and simulations, helping scientists predict where the universe’s most powerful black holes formed and how they influenced their surroundings.

Over time, this knowledge deepens our understanding of how cosmic structure emerged and how energy from black holes shaped galaxies like our own.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Colliding galaxies ignite the universe’s most powerful black holes, Euclid data finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.