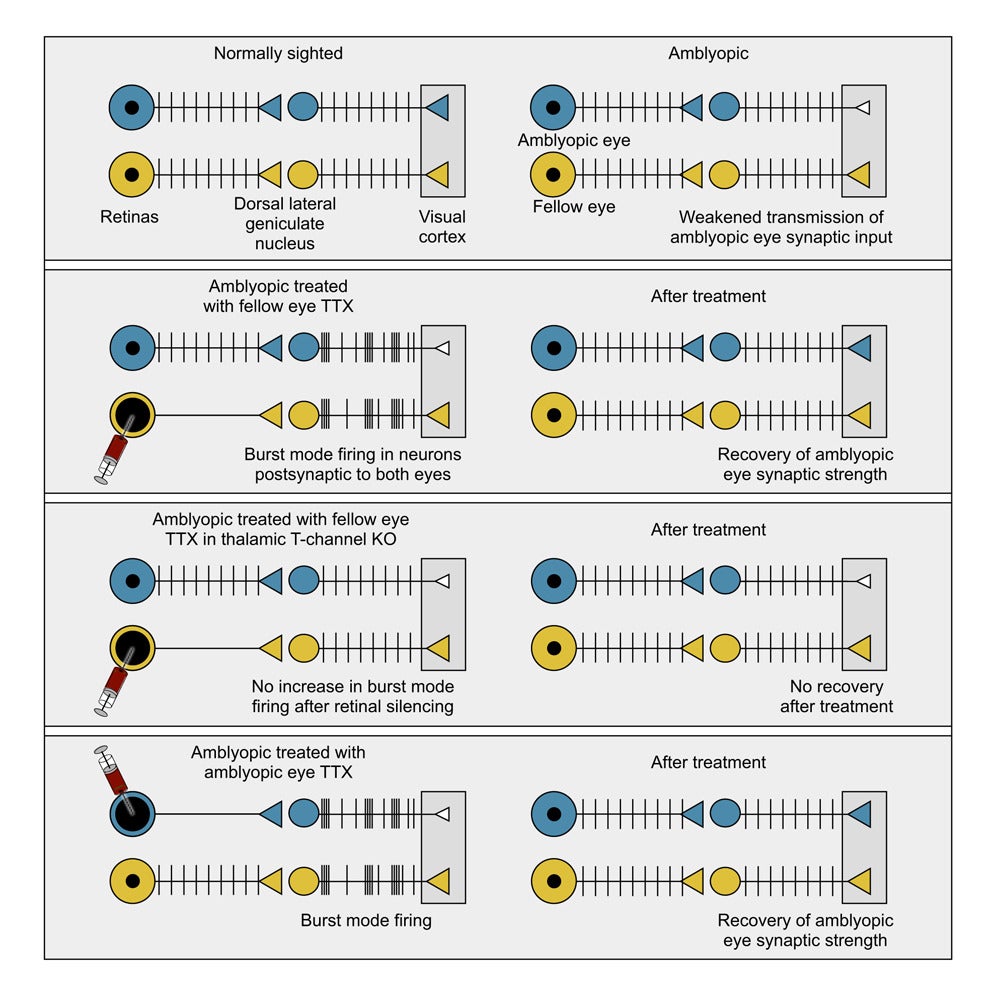

Amblyopia, often called lazy eye, develops when the brain fails to receive balanced input from both eyes early in life. One eye becomes dominant, while the other lags behind. Standard care relies on patching or blurring the stronger eye so the weaker one works harder. That method can help young children, but it only works during a short developmental window. Once that critical period ends, treatment options are limited, especially for severe cases caused by long-term visual deprivation.

Yet clinicians have long noticed something unexpected. When adults lose vision in their stronger eye due to injury or disease, the amblyopic eye sometimes improves on its own. That puzzle has driven decades of research and now, a new mouse study offers a clearer explanation. The findings suggest that briefly silencing the retina, even in adulthood, can restart a powerful form of brain plasticity deep within the visual system.

The work, led by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT, focuses on how neurons communicate in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus, or dLGN. This thalamic hub relays signals from the eyes to the visual cortex. The study shows that when retinal input is temporarily shut down, dLGN neurons shift into a distinctive firing pattern called burst mode. That change appears to be the key that unlocks recovery.

Earlier animal studies showed that injecting tetrodotoxin, or TTX, into one eye can reverse amblyopia. TTX temporarily blocks retinal ganglion cells from firing. In mice, cats, and monkeys, this approach restored visual responses even after the critical period had closed. Patching alone could not do that.

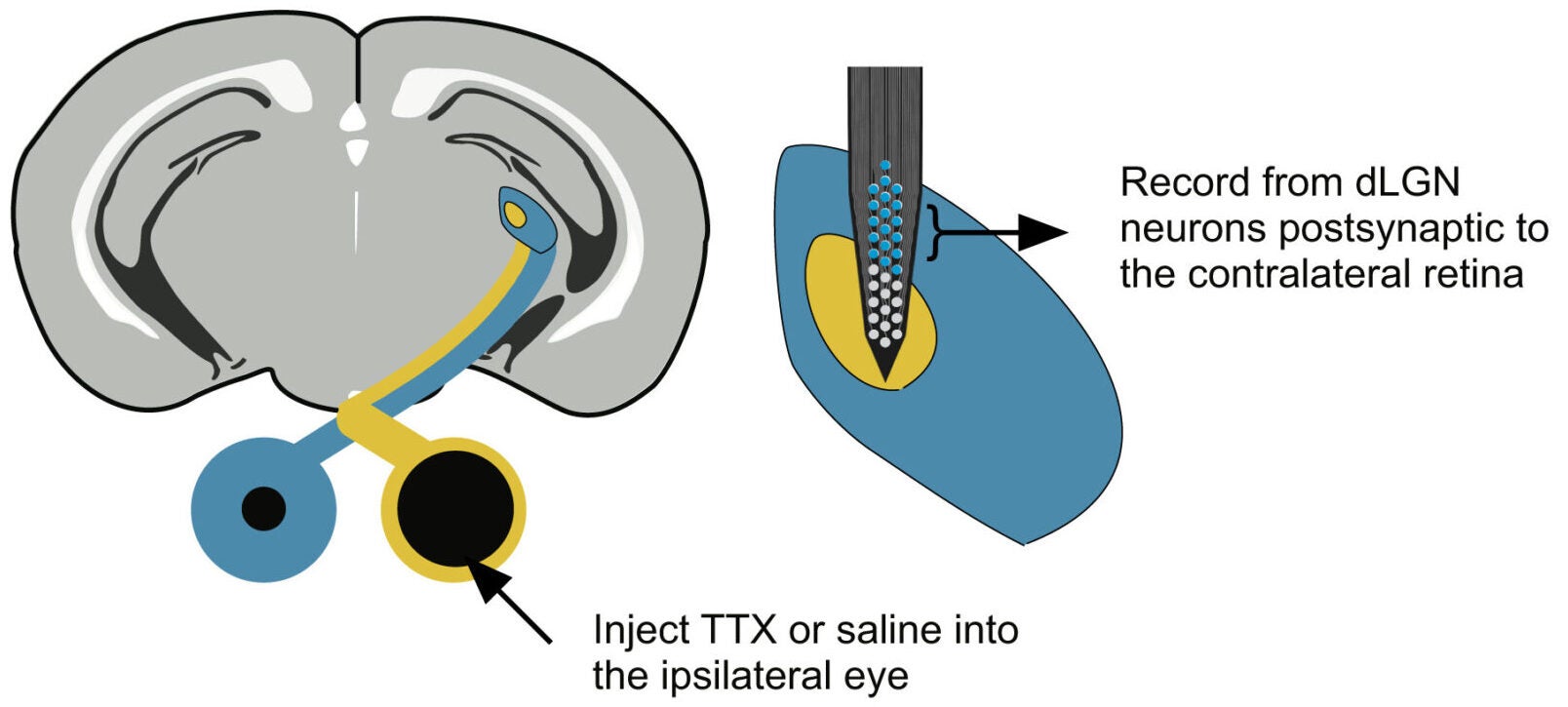

What puzzled researchers was why total silencing succeeded where patching failed. One theory suggested that removing visual input lowered the brain’s threshold for strengthening connections, similar to the effects of prolonged darkness. But experiments challenged that idea. Even silencing the ipsilateral eye, which sends relatively little input to the dLGN, could rescue responses from the opposite, amblyopic eye.

Recordings from awake animals provided a clue. When one retina is silenced, dLGN neurons do not simply fall quiet. Instead, they fire short, rapid bursts of spikes. These bursts resemble activity patterns seen before birth and during early development, when visual circuits first take shape.

The new study tested whether that burst firing is essential or merely a side effect.

“Using multi-channel probes in awake mice, we recorded dLGN neurons driven by the untreated eye. Two hours after injecting TTX into the opposite eye, these neurons showed striking changes. Spikes came closer together. Bursts of two, three, or four spikes became more common. Neurons also fired in greater synchrony with one another,” Mark Bear, a Picower Professor in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“This shift did not depend on light alone. Increased bursting appeared during visual stimulation and even, to a smaller degree, in complete darkness. The same pattern emerged in mice that already had amblyopia from weeks of monocular deprivation,” he continued.

In short, inactivating one eye caused a broad change in how dLGN neurons fired, including those connected to the other eye. The brain’s relay station entered a different mode of operation.

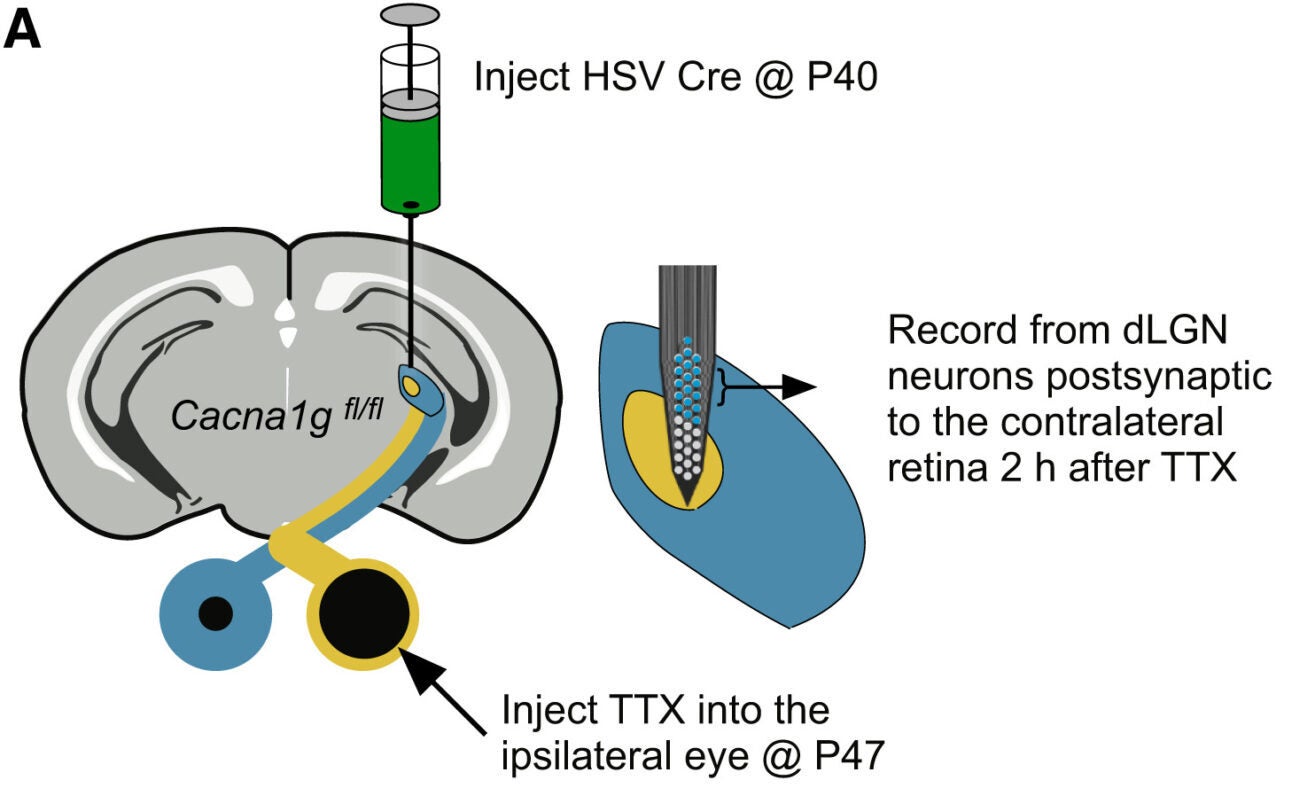

Burst firing in the thalamus depends on T-type calcium channels. The main version in the dLGN is encoded by the Cav3.1 gene, also called Cacna1g. To test whether these channels mattered, the team selectively removed them from the dLGN.

They used a herpes simplex virus carrying Cre recombinase to knock out Cav3.1 only in thalamic neurons. These thalamic T-channel knockout mice served as a critical test case. Wild-type littermates received the same virus and acted as controls.

When the ipsilateral eye was silenced with TTX, dLGN neurons in knockout mice showed far less burst firing and weaker synchrony. Importantly, their basic visual responses remained normal. Signals still reached the visual cortex, and normal eye dominance was preserved. The manipulation did not damage the tissue.

The real test came in amblyopic animals. After long-term deprivation of the contralateral eye, wild-type mice treated with fellow-eye TTX showed a clear recovery. Neurons in binocular visual cortex regained a strong bias toward the previously deprived eye. Firing rates increased, and ocular dominance indices shifted back toward normal.

That recovery vanished in knockout mice. Without Cav3.1 and burst firing, silencing the fellow eye no longer restored balance. Yet other forms of plasticity, such as stimulus-selective response plasticity, remained intact. This showed that the loss of recovery was specific, not a general failure of learning in the visual cortex.

The findings led to a bold question. If burst firing is the key, could silencing the amblyopic eye alone be enough?

To test this, researchers compared deprived mice that received no treatment with those that received TTX directly in the amblyopic eye. After the drug wore off, all animals experienced normal binocular vision for a week.

The results were striking. Mice treated in the amblyopic eye showed ocular dominance values indistinguishable from animals that had never been deprived. Responses to stimulation of the formerly weak eye rebounded fully. Simply reopening the eye without TTX did not produce the same effect.

These results suggest that burst firing in dLGN neurons linked to the amblyopic eye can substitute for normal visual experience. Brief retinal inactivation appears to recreate a developmental-like signal that allows adult circuits to strengthen weakened connections.

“This is a pretty substantial step forward,” Professor Bear said. “The amblyopic eye, which is not doing much, could be inactivated and ‘brought back to life’ instead.”

Bear emphasized the need for caution. “Especially with any invasive treatment, it’s extremely important to confirm the results in higher species with visual systems closer to our own,” he said.

The study was led by Madison Echavarri-Leet, a former graduate student whose doctoral work focused on this research. The findings were published in Cell Reports.

The researchers stress that behavioral vision tests were not included. Future work must show that neural recovery translates into better sight. Studies in cats and non-human primates are also needed before any human trials.

Still, the message is hopeful. By targeting a basic firing pattern in the thalamus, researchers may have found a way to reopen plasticity in the adult brain.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell Reports.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post MIT study reveals how vision can be restored in adults with ‘lazy eye’ appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.