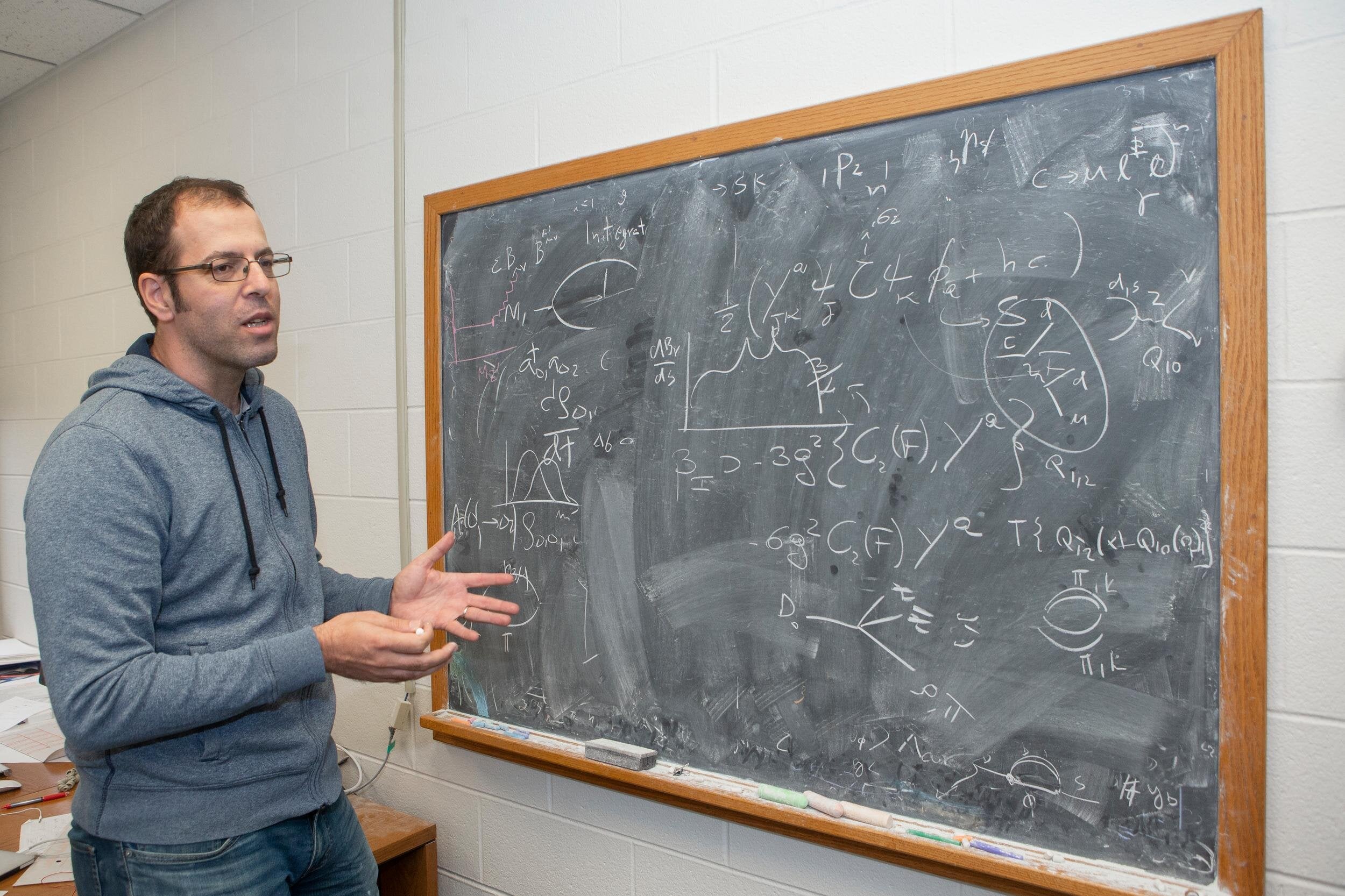

Nuclear fusion is often framed as a future source of clean energy. A new theoretical study is looking at them differently. University of Cincinnati physics Professor Jure Zupan, working with theorists at Fermi National Laboratory, MIT, and the Technion–Israel Institute of Technology argue that fusion reactors could also serve as powerful laboratories for discovering new subatomic particles that fall outside the Standard Model of physics.

Most searches for these weakly interacting, lightweight particles focus on the Sun or on nuclear fission reactors. Those environments already place strict limits on many theories. Fusion reactors, however, have largely been overlooked. The new work suggests this gap has less to do with physics and more to do with habit.

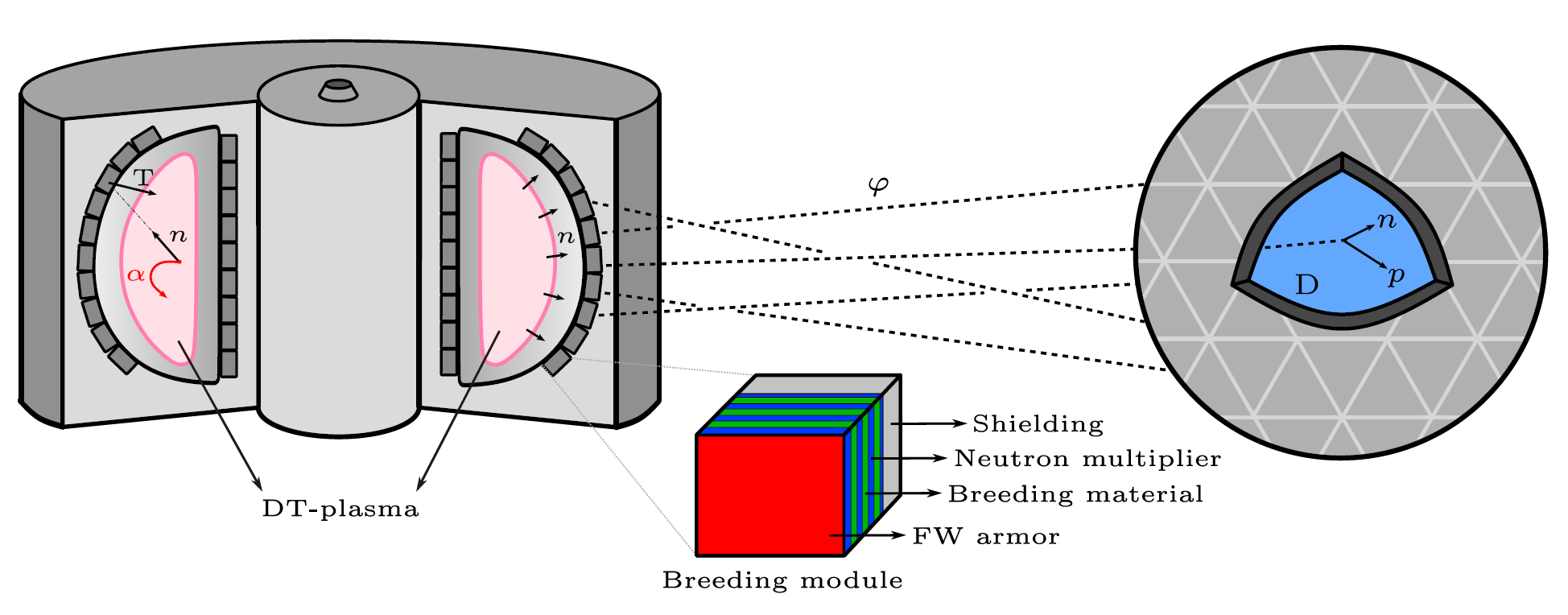

The study examines deuterium–tritium fusion, the reaction planned for next-generation reactors. Each fusion event releases 17.6 million electronvolts of energy. About 3.5 MeV stays in the plasma as a helium nucleus, helping sustain the reaction. The remaining 14.1 MeV is carried by a fast neutron that escapes into the reactor walls.

Those neutrons matter. In a fusion plant producing about 2,000 megawatts of power, the neutron flux near the inner wall could reach roughly 10¹⁵ neutrons per square centimeter per second. That is about 100 times higher than in a fission reactor of similar output. With so many energetic neutrons, even extremely rare processes can become visible.

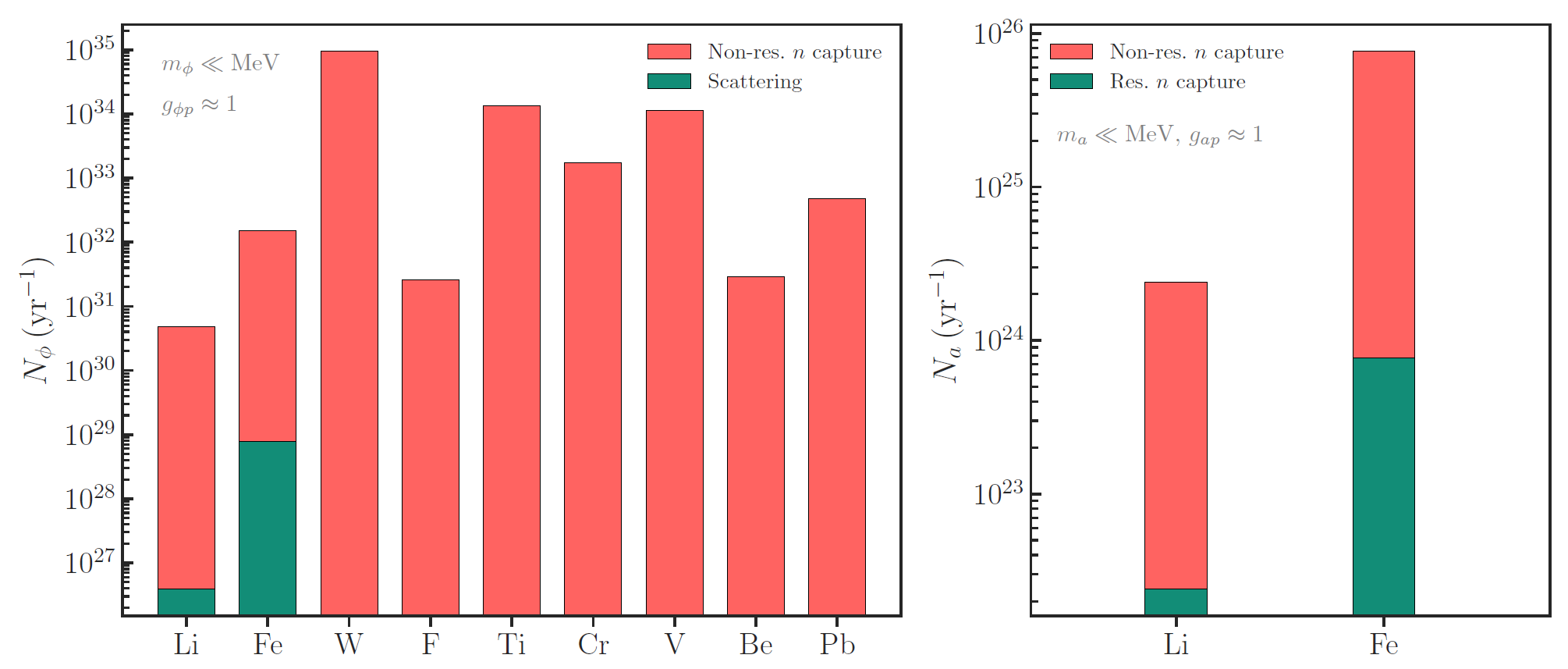

To keep the discussion grounded, the authors focus on two hypothetical spin-0 particles. One is a light scalar particle, labeled ϕ. The other is a light pseudoscalar known as an axion-like particle, or ALP. Both interact very weakly with ordinary matter and have long been candidates for new physics. Axions are a leading hypothetical candidate for dark matter.

The scalar particle can couple to photons, electrons, and nucleons. In many realistic models, its interaction with protons and neutrons is far stronger than with electrons. The pseudoscalar has a similar pattern. Its couplings are set by a decay constant and dimensionless coefficients, and for typical choices, nucleon interactions again dominate.

The study concentrates on particle masses in the range where decays into electron–positron pairs are allowed but decays into heavier particles are not. In this window, the particles mostly decay into electrons. Those decays happen slowly. A particle with a mass of 10 MeV and a small electron coupling could travel kilometers before decaying. That distance is far larger than a reactor wall, making escape likely.

The central idea is simple. When fusion neutrons hit materials in the reactor wall, they can create these hidden particles. Reactor designs commonly include lithium-based breeding blankets to generate tritium fuel, along with steel structures for support. Neutrons interact frequently with lithium and iron nuclei in these materials.

“When a neutron is captured by a nucleus, the nucleus becomes excited and then relaxes. It usually emits a gamma ray. If new physics exists, it can sometimes emit a light scalar or ALP instead. Neutrons can also scatter off nuclei and lose energy. In that process, a new particle can be radiated through bremsstrahlung, or braking radiation,” professor Zupan explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“For axion-like particles, we connect production rates to well-studied magnetic dipole transitions in nuclear physics. By comparing axion emission to known gamma emission rates in lithium and iron, we can estimate how often ALPs are produced. This approach uses measured neutron capture data and established nuclear parameters,” he continued.

Scalar production is harder to pin down. There is no direct electromagnetic process that mirrors scalar emission. The authors rely on dimensional analysis to estimate how often scalars would be emitted compared with electric dipole photons. They are clear that uncertainties remain large and that detailed nuclear calculations could change the numbers substantially.

To stay realistic, the study models a reactor similar to the planned DEMO facility, which includes a water-cooled lithium–lead breeding blanket and EUROFER97 steel. Using standard densities and dimensions, the authors estimate trillions of trillions of target nuclei available for neutron interactions. That enormous number underpins the entire proposal.

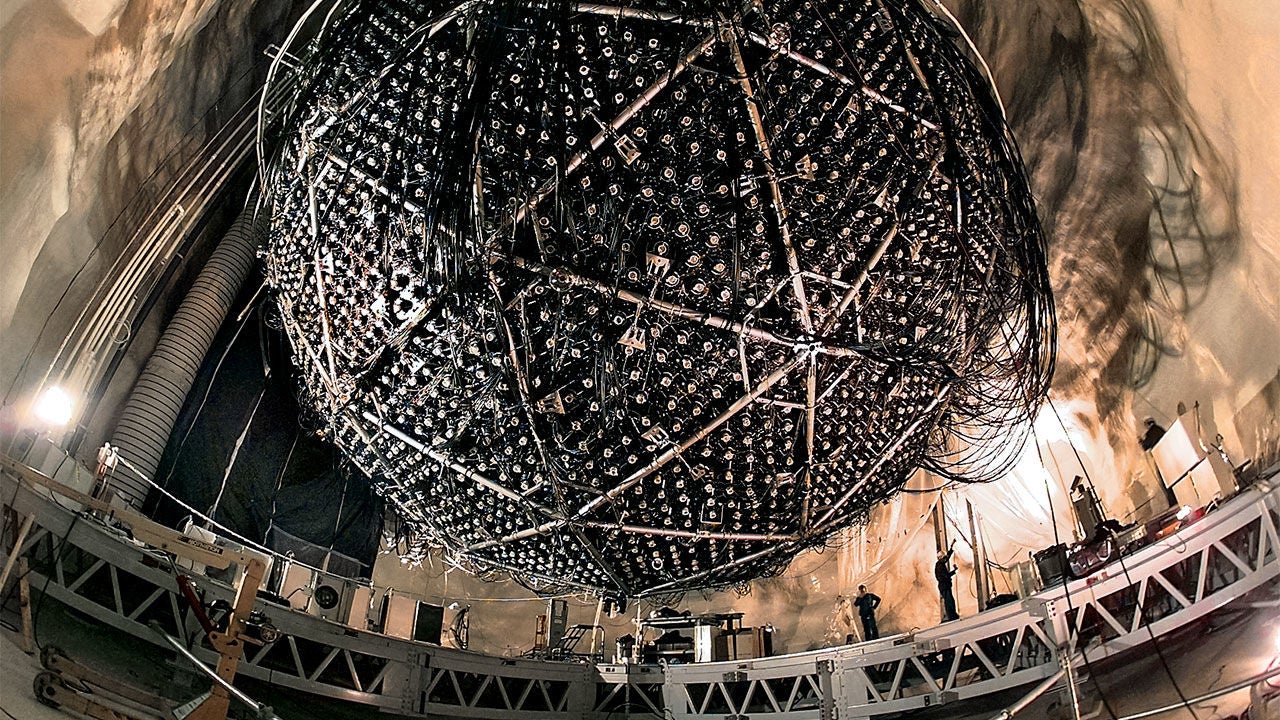

Production alone is not enough. To test these ideas, the particles must be detected. The authors propose a heavy-water detector similar to the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory. About 1,000 tons of heavy water would provide roughly 6 × 10³¹ deuterium nuclei.

When a scalar or ALP reaches the detector, it can break a deuteron into a proton and a neutron. This reaction requires at least 2.2 MeV of energy, which is well within reach of particles produced in the reactor walls. The researchers calculate dissociation rates for both scalars and pseudoscalars, showing how the rates depend on particle energy and proton couplings.

Placing such a detector about 10 meters from a 2,000 MW fusion reactor and running it for one year could yield detectable signals. The main background would come from solar neutrinos, producing about 4,800 similar events per year. Reactor neutrinos are not a concern because their energies are too low. By comparing reactor on and off periods and using the Sun’s direction, the background could be measured and reduced.

If fusion reactors can double as particle physics laboratories, they offer a new way to search for dark matter candidates such as axions. This approach could complement existing experiments without requiring entirely new facilities.

As fusion plants are built for energy production, adding detectors could expand their scientific value.

Over time, this strategy may help clarify the nature of dark matter and deepen understanding of fundamental forces, while advancing clean energy goals.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of High Energy Physics.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Fusion reactors may be the key to uncovering dark matter particles appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.