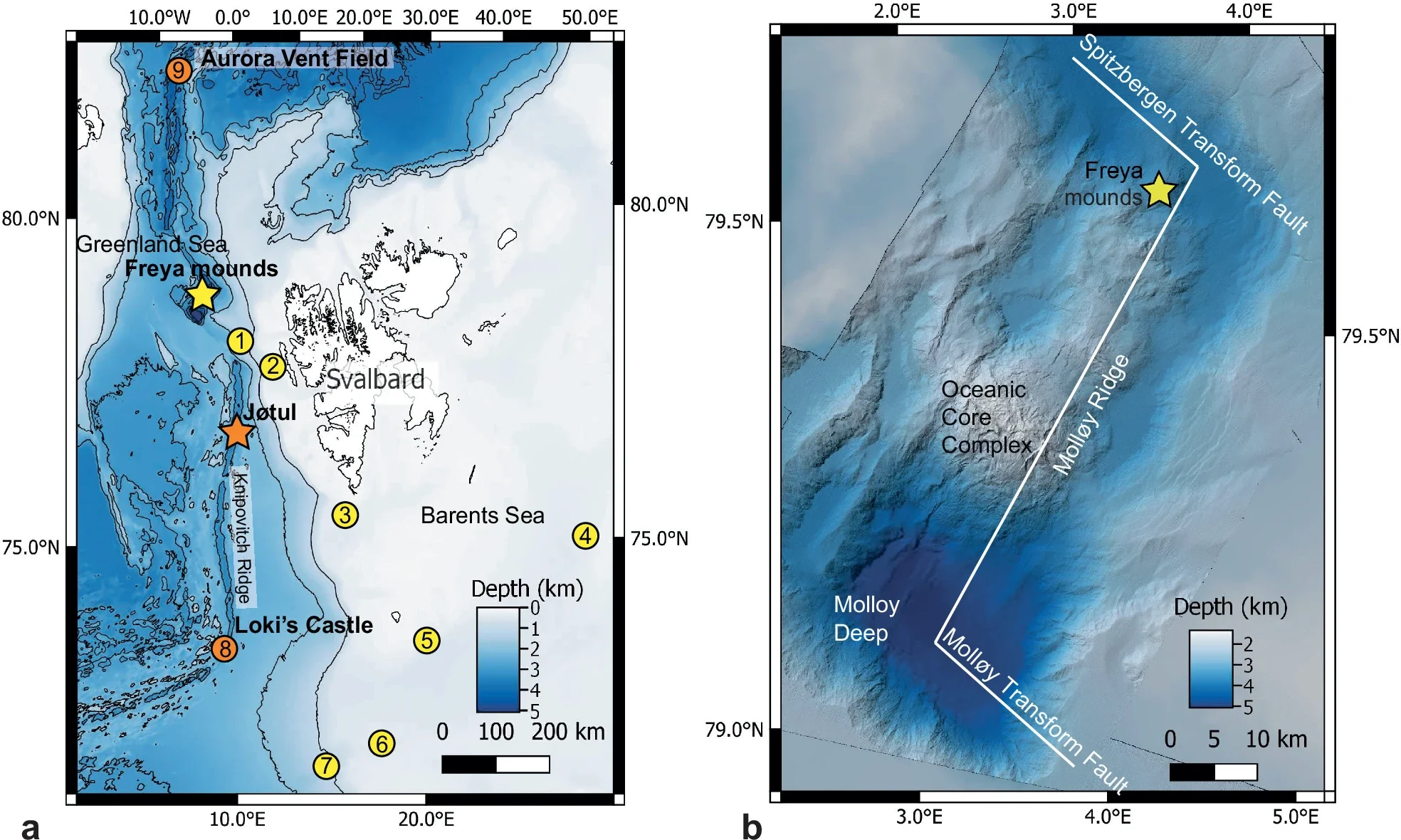

Far north in the Fram Strait, scientists from UiT The Arctic University of Norway, working with colleagues including the University of Southampton in the U.K., have identified the deepest known gas hydrate cold seep on Earth. The multinational team traced a huge methane flare to the Molloy Ridge during the Ocean Census Arctic Deep – EXTREME24 expedition in May 2024. They named the site the Freya gas hydrate mounds, and they reported the findings in Nature Communications.

The mounds sit about 3,640 meters down, deeper than any previously confirmed gas hydrate outcrops. Two bubble plumes rose off the ridge, with one flare climbing at least 3,350 meters up the water column. The plume stopped roughly 290 meters below the surface, where the water measured 2.63 degrees Celsius. By height, it ranks among the tallest gas flares recorded worldwide.

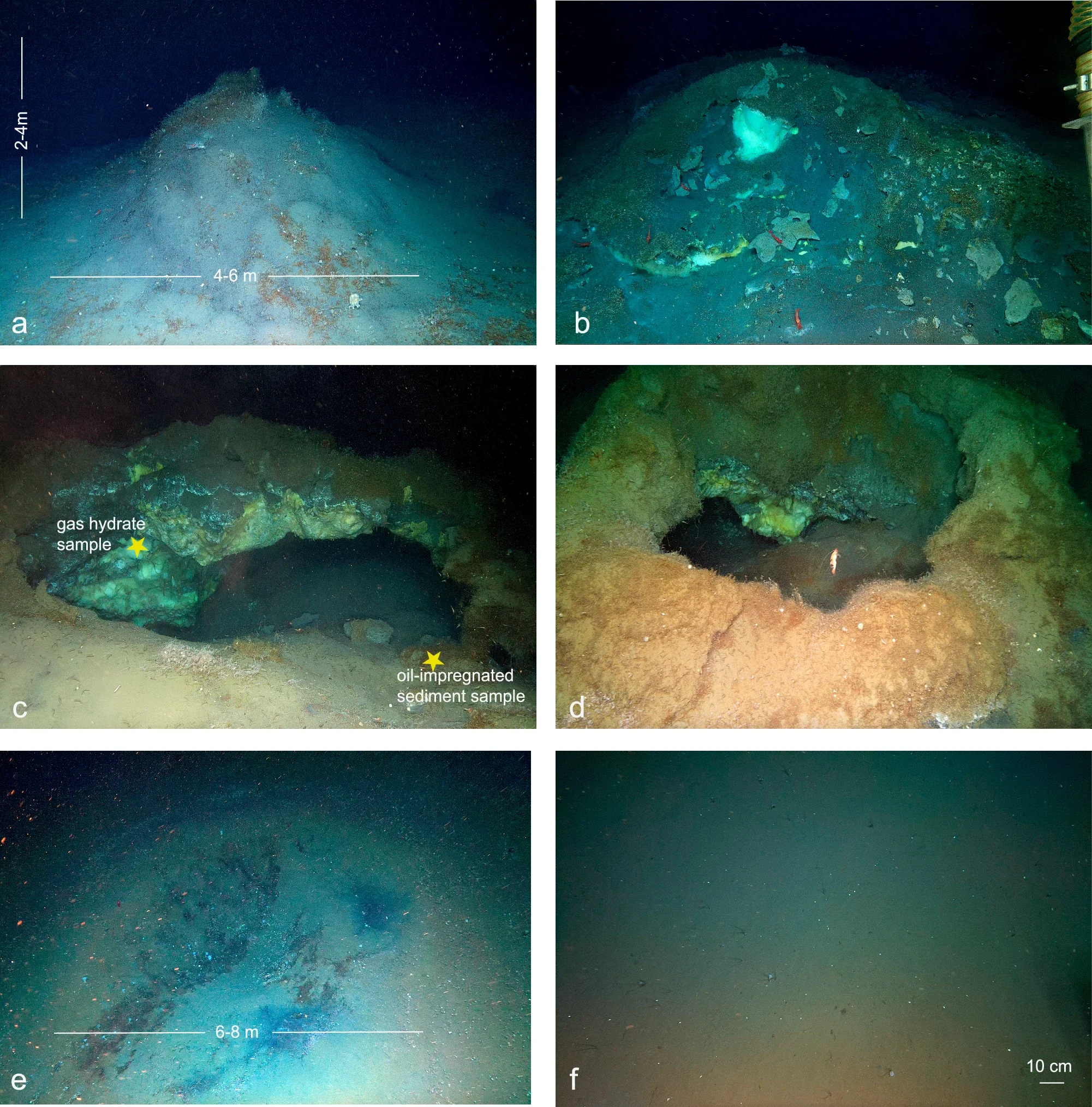

A remotely operated vehicle then revealed three hydrate mounds, small ridges, and collapse pits across a patch of seafloor about 100 meters by 100 meters. Video also captured active methane seepage and crude oil leaking from the seabed. For you, the discovery adds a rare data point in a place where the carbon story is still incomplete.

Gas hydrates form when water freezes around gas molecules under high pressure and low temperature. Many known deposits sit on continental slopes, often deeper than about 400 meters, where gases move upward through faults and porous sediments. In the Arctic, cold bottom water can keep hydrates stable even at shallower depths. Freya shows the other extreme, hydrates can also persist far deeper than most known outcrops.

Chemical measurements show that Freya’s hydrate gas is a hydrocarbon mix dominated by methane, about 66% (C1). It also includes ethane at about 8% (C2), propane at about 14% (C3), isobutane near 3% (i-C4), and normal butane around 2.3% (C4). The methane-to-heavier ratio, C1/(C2 + C3) of roughly 3.0, plus carbon and hydrogen isotopes, point to thermogenic gas. That means the fuel formed when deeply buried organic material broke down under high temperature and pressure.

The methane’s carbon isotope value is about −47‰, and its hydrogen isotope value is around −188.5‰. Carbon dioxide linked to the gas is relatively heavy, with a δ¹³C near +0.6‰. The team also found oil-related biomarkers that match source rocks laid down in freshwater or brackish lake settings. Those rocks received strong inputs from angiosperms, flowering plants that were widespread in the Arctic during the Miocene.

On the seafloor, the hydrate mounds look like small cones, roughly 4 to 6 meters across and 2 to 4 meters tall. They are often dusted with soft sediment and sometimes capped by thin carbonate crusts. Dense stands of tubeworms help stabilize the surface. ROV footage suggests the mounds pass through stages that resemble a life cycle.

Some mounds stay buried, showing only low domes. Others expose bright hydrate at the top. More degraded mounds appear fractured into arches and cave-like shapes, where cracks open as hydrate breaks down. Nearby, pit-like collapse features about 6 to 8 meters across mark places where a mound likely disintegrated.

This matters because hydrate breakdown releases gas and freshwater that can loosen sediment and strip away hard surfaces. The study describes the deposits as metastable, meaning they can form, erode, and collapse repeatedly.

Water measurements help explain why the bubble plume can climb so high. Near the seafloor, the CTD recorded about −0.63 degrees Celsius at around 12 meters above bottom. As bubbles rise, they first stay within the hydrate stability zone, where a thin hydrate “skin” can form and slow dissolution. Higher up, water warms, reaching about 2.60 degrees Celsius near 300 meters depth. Modeling places the stability boundary around 297 meters, above which the protective coating fails and bubbles dissolve much faster.

Even with that limit, multibeam data show a plume stretching more than 3,300 meters. ROV footage captured unusual flat-shaped bubbles that likely carried coatings of both oil and hydrate. Oil films can help bubbles survive longer, which may allow methane and other hydrocarbons to travel unusually far into the water column.

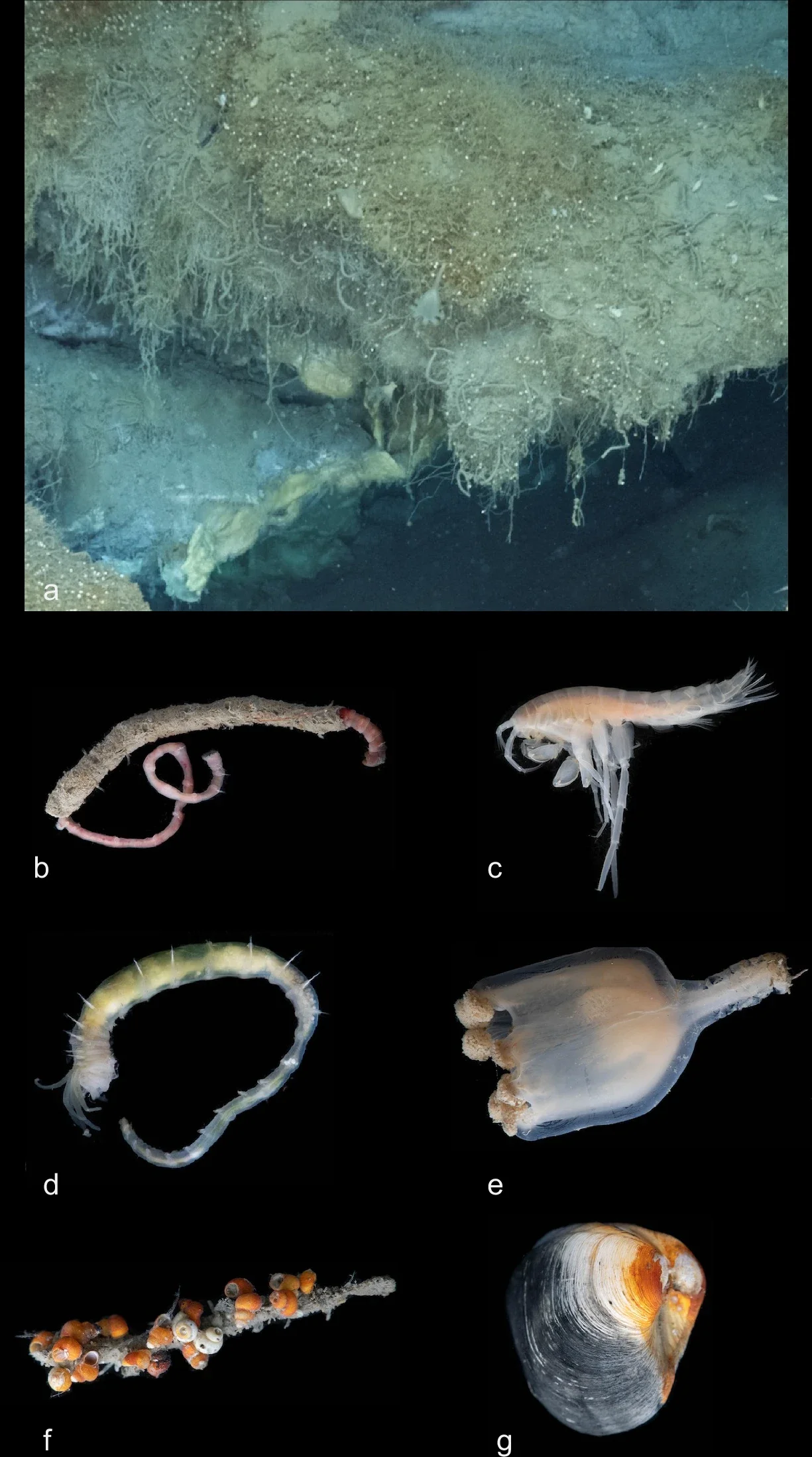

Despite the cold and pressure, the Freya site hosts a rich community, with more than 20 visible faunal morphospecies. The most striking feature is a dense “Sclerolinum forest” of siboglinid tubeworms, Sclerolinum cf. contortum, covering mound surfaces and edges. Their tubes create a three-dimensional scaffold that shelters microbes and small grazers.

Giuliana Panieri, a professor at UiT and now Director of CNR-ISP, served as chief scientist of the expedition told the Brighter Side of News, “Our team observed maldanid tubeworms in surrounding sediment, plus amphipods, red caridean shrimps, pycnogonids, and nemertean worms. Stalked, jellyfish-like stauromedusae, identified as Lucernaria cf. bathyphila, cling to tubeworm tubes. Tiny rissoid and skeneid snails, only 2 to 3 millimeters long, cluster in high densities. The site also includes the stalked sponge Caulophacus cf. arcticus and fish such as Lycodes cf. frigidus and Lycenchelys cf. platyrhina.”

“Community patterns shift with geology. Intact mounds with stronger seepage support denser tubeworm stands. Collapse pits tend to look sparser and more mobile-animal heavy. When you follow that pattern, you see ecological succession tied to the rise and fall of hydrate structures,” she continued.

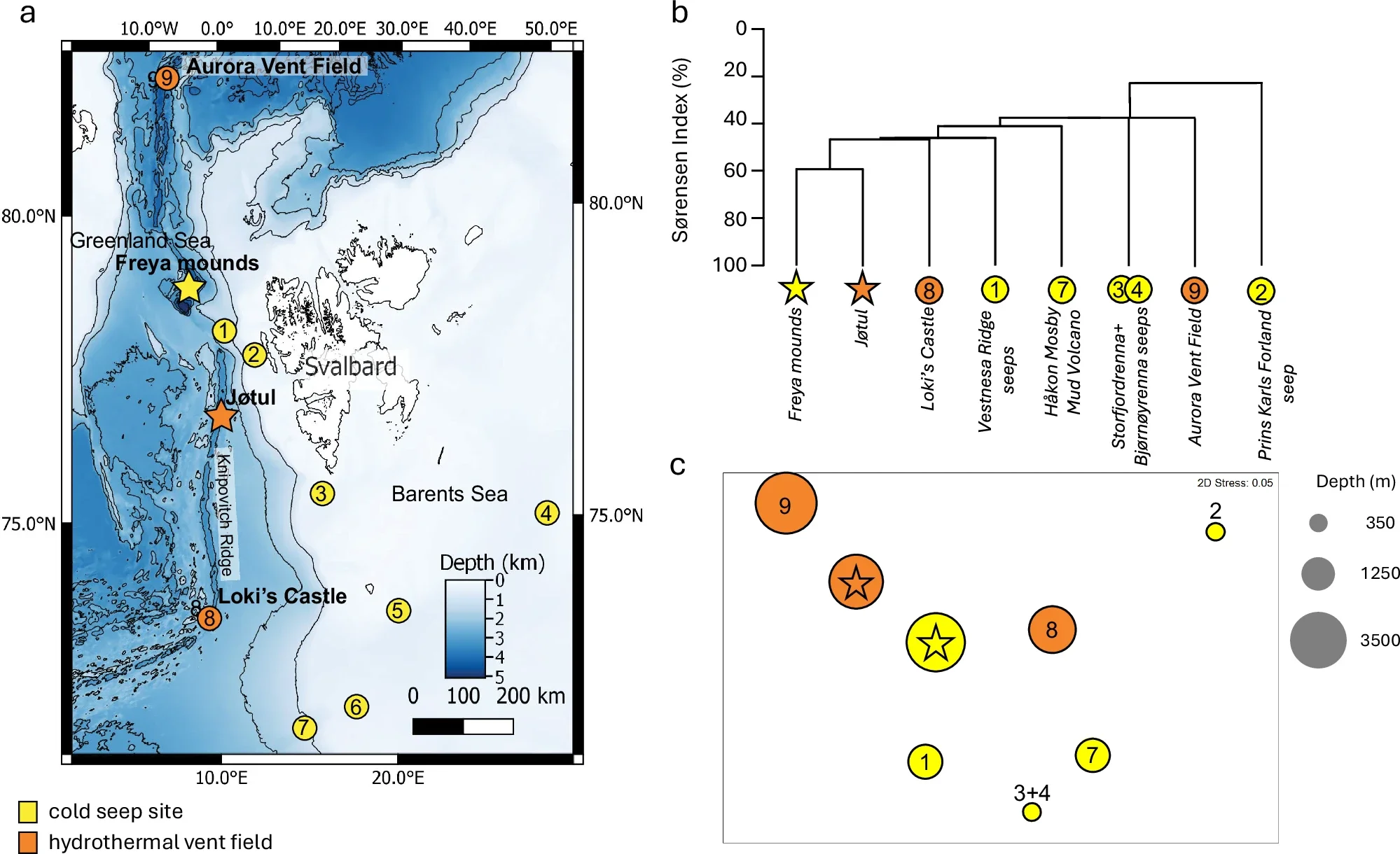

The expedition also sampled fauna from the Jøtul hydrothermal vent field, about 266 kilometers south at 3,020 meters depth on the Knipovich Ridge. Jøtul sits on basalt and hydrothermal precipitates, unlike Freya’s sediment-coated hydrates and carbonates. Yet the sites share many of the same families, including Sclerolinum cf. contortum, melitid amphipods, caridean shrimps, and skeneid and rissoid snails. At the family level, Jøtul shows 59% Sørensen Index similarity with Freya.

“This discovery rewrites the playbook for Arctic deep-sea ecosystems and carbon cycling,” Panieri said. “We found an ultra-deep system that is both geologically dynamic and biologically rich, with implications for biodiversity, climate processes, and future stewardship of the High North.”

Jon Copley of the University of Southampton, who led the biogeographic analysis, emphasized both the likelihood of more sites and the stakes of protecting them. “There are likely to be more very deep gas hydrate cold seeps like the Freya mounds awaiting discovery in the region, and the marine life that thrives around them may be critical in contributing to the biodiversity of the deep Arctic” Copley said. “The links that we have found between life at this seep and hydrothermal vents in the Arctic indicate that these island-like habitats on the ocean floor will need to be protected from any future impacts of deep-sea mining in the region.”

That warning lands amid policy pressure. Norway opened an area between Jan Mayen and Svalbard for deep-sea mining activities in April 2024, within Norway’s extended Exclusive Economic Zone. Licensing for exploration was paused in December 2024, but the study argues that development could return. For you, Freya becomes more than a scientific headline. It becomes a test case for how the Arctic balances discovery, extraction, and protection.

Freya gives researchers a new natural laboratory for tracking methane behavior in extreme deep water. The site can help refine models of how gases move, dissolve, or persist as they rise, especially when bubbles carry hydrate skins or oil films. That work matters for climate science because methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and deep-ocean pathways affect how much of it ever reaches shallower waters.

The discovery also reshapes biodiversity planning in the High North. By showing strong overlap between seep and vent communities, the study suggests these habitats may function as connected “stepping stones” for species that can colonize without feeding larvae. That insight can guide future surveys, conservation mapping, and environmental impact assessments. It also raises the bar for responsible management, because damage to one habitat type could ripple into the other.

Finally, Freya strengthens the case for evidence-based Arctic governance. As interest in deep-sea mining grows, policymakers can use discoveries like this to define what counts as vulnerable habitat, where protections should apply, and what baseline studies must happen before any industrial activity begins.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Deepest Arctic methane seep found at 3,640 meters reveals thriving life appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.