The global food system sits at the center of a growing contradiction. It produces enough food to nourish everyone, yet more than 620 million people still go hungry each day. At the same time, the way food is grown, processed, transported, and eaten generates roughly one-quarter to one-third of all human-made greenhouse gas emissions. As population rises and diets grow richer, that tension becomes harder to ignore. Feeding everyone well now depends on cutting emissions sharply, without denying food to those who already lack it.

That challenge is the focus of a new study led by Dr. Juan Diego Martinez at the University of British Columbia, conducted through its Institute for Resources, Environment and Sustainability. The research asks a direct question. Who, exactly, must change their diets if the world hopes to limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels?

The answer shifts attention away from nations as a whole and toward people within them. Responsibility for food-related emissions, the study shows, is deeply unequal. Some groups eat far more climate-intensive diets than others, even inside the same country. Recognizing that inequality matters for climate policy, and for fairness.

“To understand responsibility, our research team looked at food emissions from the consumer side rather than the farm gate. Most global statistics assign emissions to where food is produced. This study instead focused on where food is eaten, since diets drive demand,” Dr. Martinez explained to The Brighter Side of News.

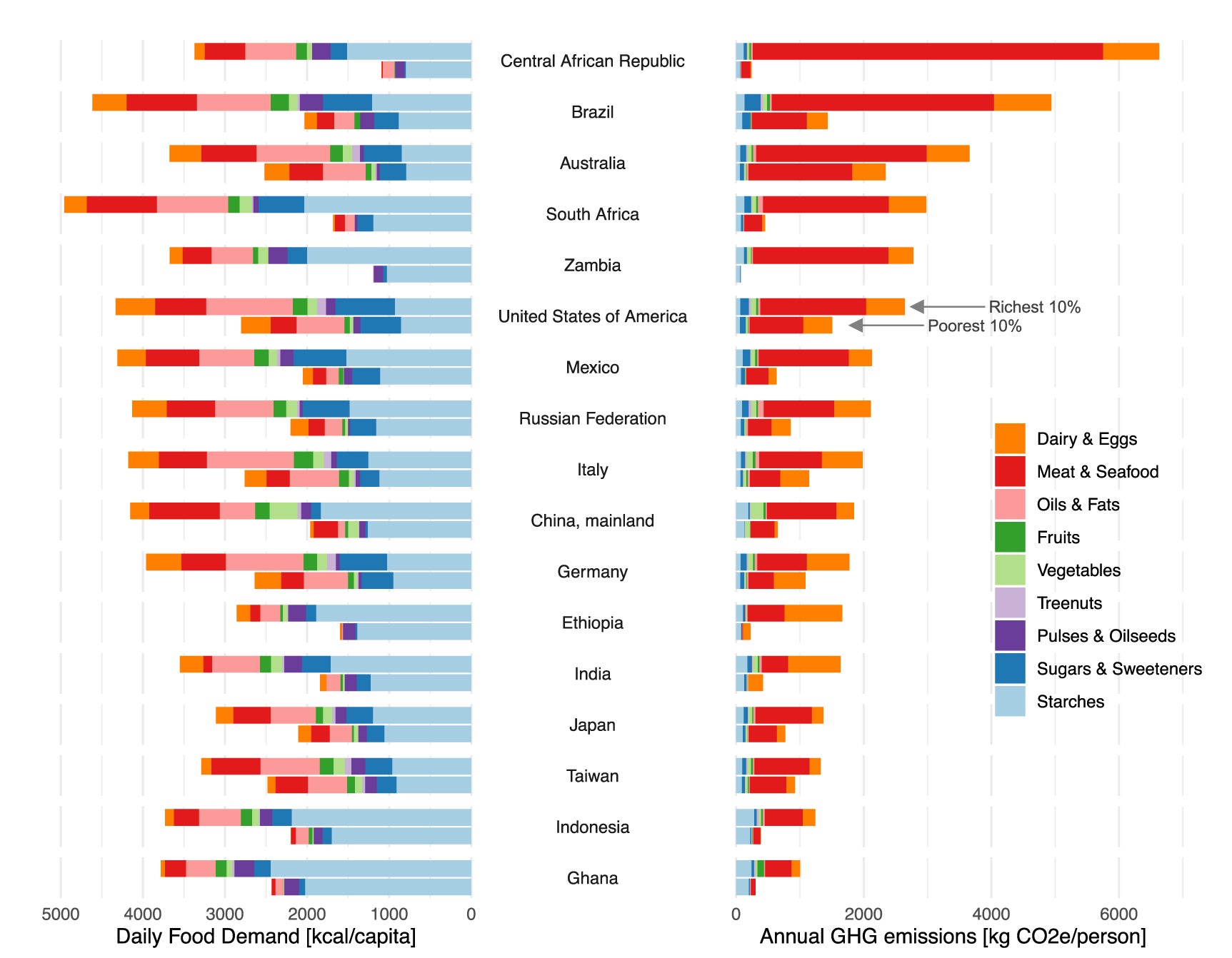

“Using United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization data, we estimated consumption-based food emissions for 140 countries and 17 food groups, averaged over 2011 to 2013. We excluded emissions from land-use change, such as deforestation, treating those separately. That choice avoids penalizing countries still clearing land today more than those that cleared forests long ago,” he continued.

The researchers then examined how food is shared within countries. They used earlier modeling that estimated daily calorie access for ten income groups in 135 countries. That model links national income, food supply, and household survey data to show how diets differ by income level. After aligning both datasets, the final analysis covered 112 countries, representing nearly 89 percent of the world’s population and almost all food-related emissions at the time.

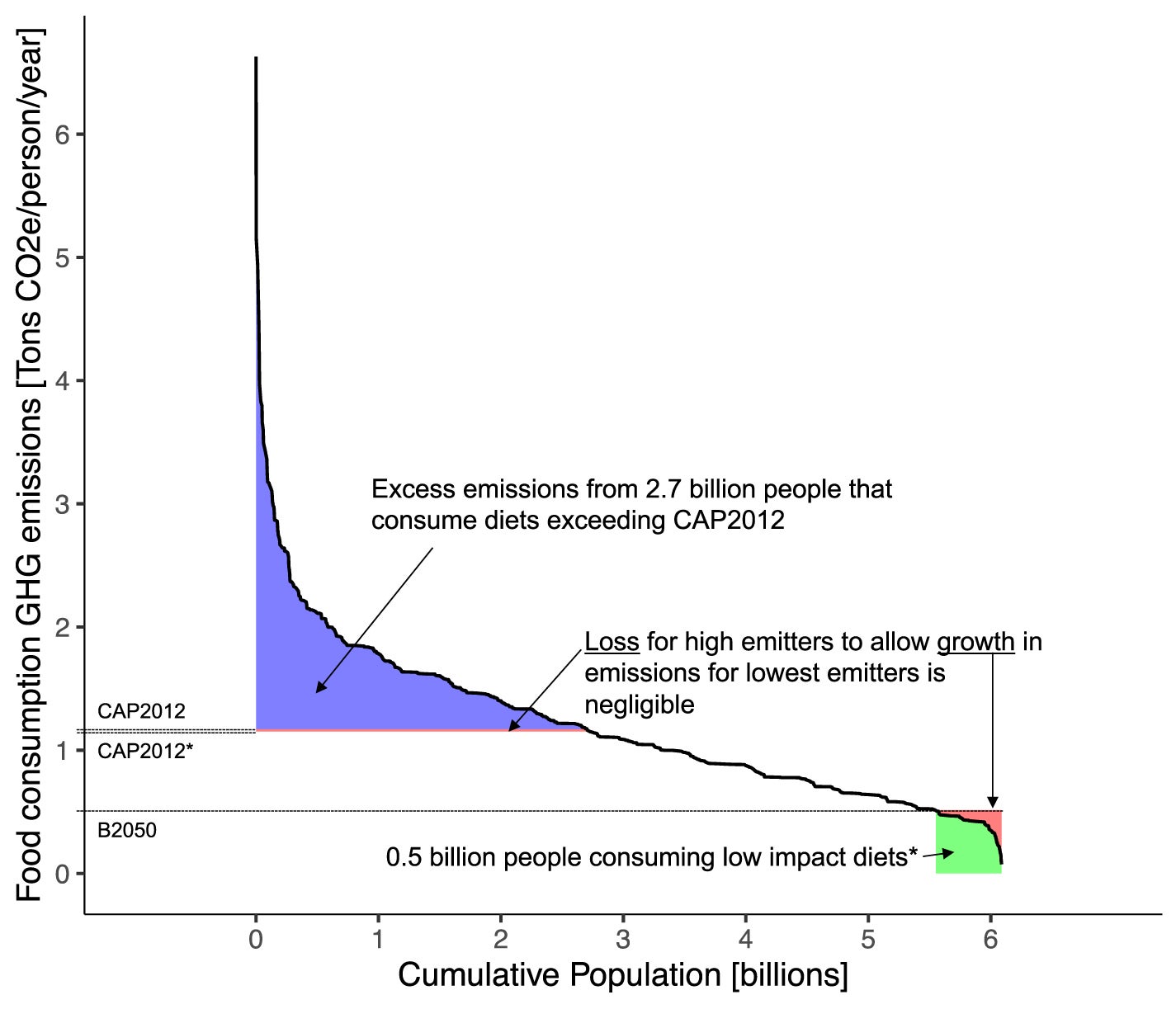

Finally, the team set a climate limit for food. They used a widely cited proposal that caps non-carbon dioxide emissions from food production at five gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. That level aligns with keeping warming below 2 degrees Celsius. Dividing that budget by global population yields a per-person emissions cap, which the researchers then used to see who exceeds it.

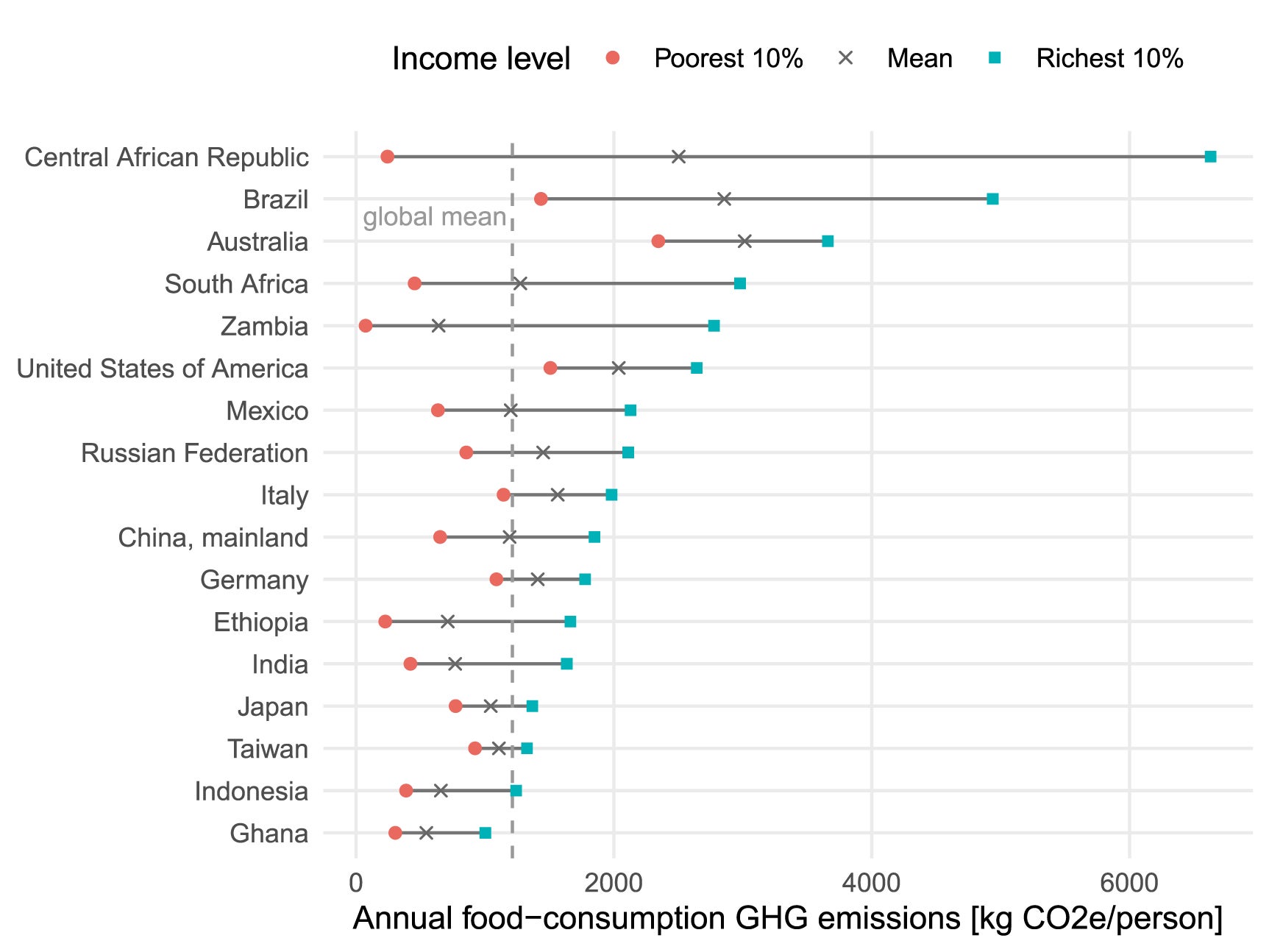

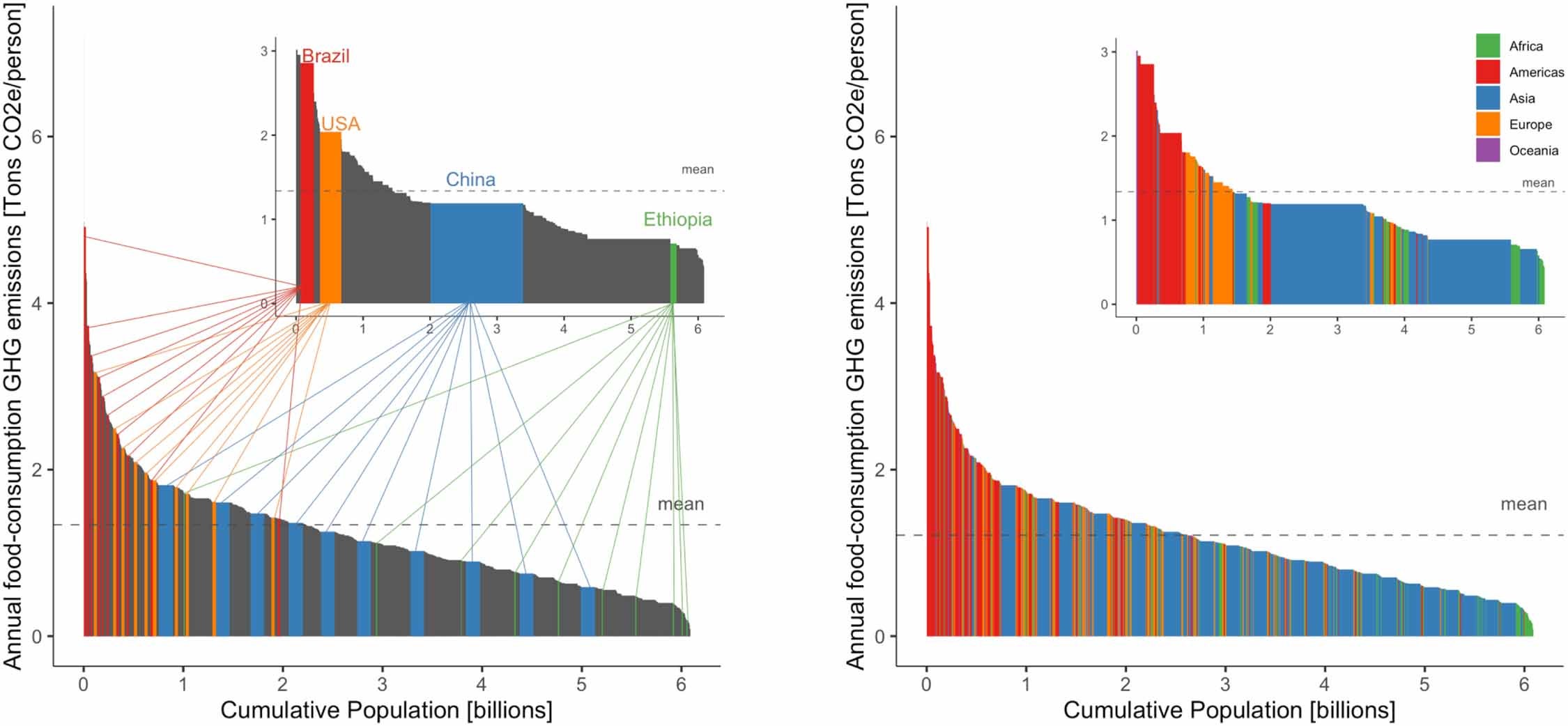

The results reveal striking gaps. Food-related emissions for the poorest 10 percent of people in Zambia amount to just 74 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. For the richest 10 percent in the Central African Republic, emissions reach 6,629 kilograms per year. The global average in 2012 was 1,213 kilograms per person.

Looking within countries often reveals wider gaps than national averages suggest. About 30 percent of all food emissions come from the top 15 percent of emitters. That equals the combined emissions of the bottom half of the global population. Measures of inequality show that differences between countries and differences within them both matter, with global inequality higher than either alone.

Regional patterns stand out. In the Americas, wealthy income groups tend to have especially high emissions due to diets rich in animal products and calorie-dense foods. In China, national averages remain below the global mean, yet the top income groups already exceed it. This shows how quickly dietary shifts can raise emissions in growing economies.

The Central African Republic offers an extreme example. The richest 10 percent there show the highest emissions of any income group worldwide, and the largest gap with the poorest. The study notes that these figures likely reflect emissions driven by a very small elite, combined with emission-intensive meat and seafood production.

Across the data, animal-based foods dominate the climate footprint. Meat, dairy, and seafood produce far more emissions per calorie than plant-based foods. The study confirms that richer populations consume far more of these products, while poorer groups often lack access altogether.

In many countries, meat-heavy diets among a small wealthy group account for a large share of national food emissions. This reinforces a central point. Reducing emissions depends heavily on changes among high-consuming groups, while allowing lower-income populations to eat more diverse and nutritious diets as needed.

Assuming that 70 percent of required cuts come from diet changes, the researchers calculated a per-person food emissions cap of 1.17 metric tons per year in 2012. That is already below the global average at the time. Under this scenario, 44.4 percent of the world’s population exceeded the cap, meaning their diets alone would prevent meeting the climate target.

The picture becomes starker when looking to 2050. With a larger population sharing the same five-gigaton budget, the per-person target falls to just 0.51 tons per year. Based on 2012 diets, about 91 percent of people already exceeded that future limit. Those below it were largely nutrition insecure.

The researchers adjusted the cap to allow low-emitting groups to increase their food emissions up to healthier levels. This barely changed the burden on high emitters. The cap for top consumers fell by only about 20 kilograms per year, roughly the emissions from producing 200 grams of beef. The share of people exceeding the cap stayed almost the same.

The study aligns with earlier research, including work modeling adoption of the EAT-Lancet diet worldwide. That research found that 57 percent of the global population consumes more climate-intensive diets than the planet can afford. Despite different data and methods, both approaches reach a similar conclusion. Large numbers of people, not only the very richest, must change what they eat, while poorer groups must be allowed to eat more.

Dr. Martinez summarized it this way. “Half of us globally and at least 90 per cent of Canadians need to change our diets to prevent severe planetary warming.” He added that this estimate is conservative, since both population and emissions have grown since 2012.

Food systems account for more than one-third of human greenhouse gas emissions. While cutting flights and driving less remain important, food is universal. Everyone eats, so everyone can act.

“We found that the 15 per cent of people who emitted the most account for 30 per cent of total food emissions, equaling the contribution of the entire bottom 50 per cent,” Martinez said. In Canada, he noted, all income groups exceed the food emissions cap.

Asked what changes matter most, Martinez pointed to waste and meat. “Eat only what you need. Repurpose what you don’t,” he said. He also stressed reducing beef consumption, which accounts for 43 percent of food emissions in the average Canadian diet.

The findings reshape how climate responsibility is understood. Instead of blaming entire countries, the research highlights high-emitting diets within them. That insight can guide fairer policies, such as targeting emission-intensive foods, improving access to plant-based options, and reducing waste.

For science, the study shows the value of linking emissions data with income and diet. Future research can refine these estimates and better connect climate goals with nutrition and health outcomes. For society, the message is practical. Allowing poorer populations to eat better barely affects climate limits. Most reductions must come from those who already eat more than enough.

Changing diets, especially reducing animal-based foods and waste, offers a direct way to protect both people and the planet.

Research findings are available online in the journal Environmental Research Food Systems.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Changing your diet could help save the world, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.