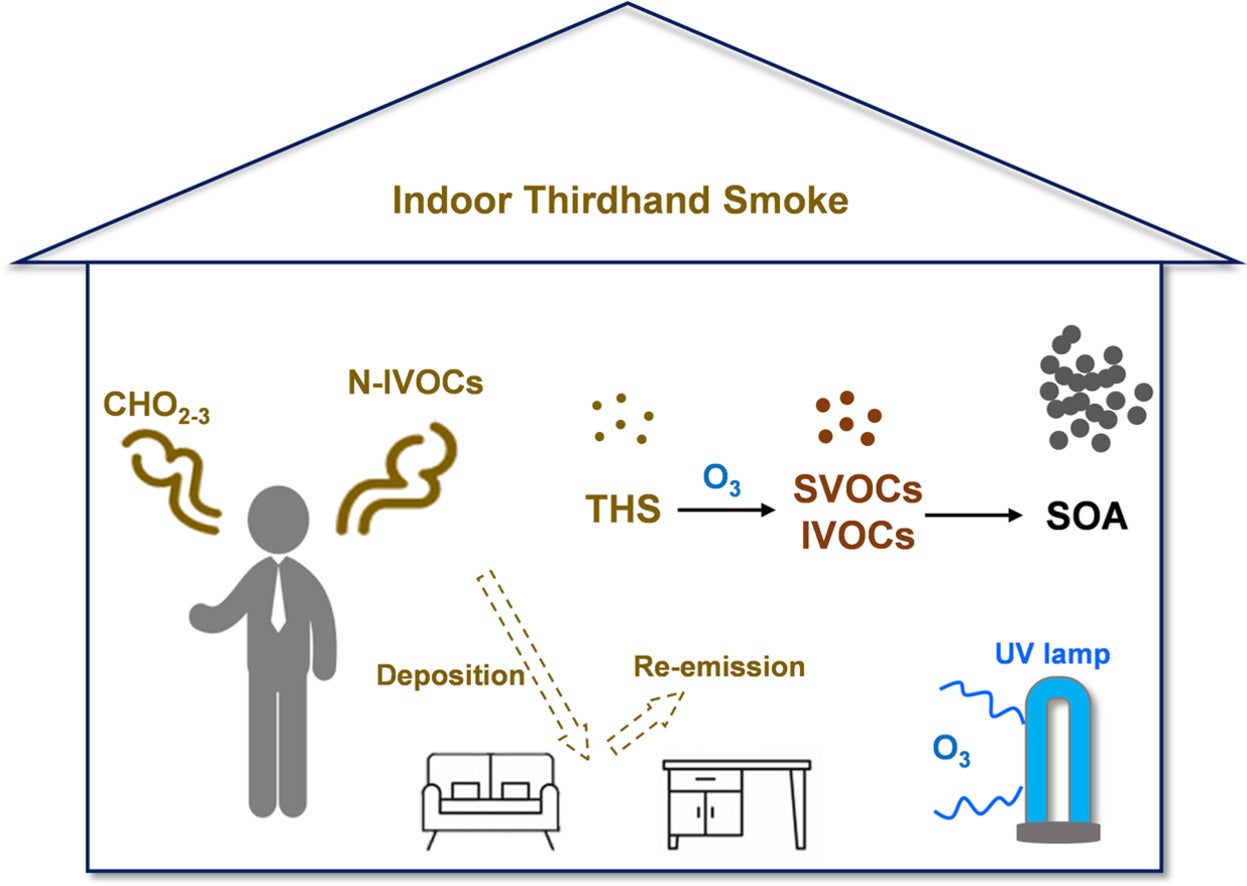

You already know secondhand smoke is dangerous. A new study from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences shows a quieter threat can linger much longer indoors: thirdhand smoke. It is the residue that settles onto walls, carpets, furniture, clothing, and even skin and hair after smoking ends. Over time, those residues can drift back into the air or react with other indoor chemicals and form new pollutants.

The research, published in Building and Environment, was led by a team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, with Professor Yele Sun as the corresponding author. The scientists tracked thirdhand smoke in a real workplace and then recreated key conditions in a lab chamber to understand how the residue behaves and changes.

Thirdhand smoke matters because exposure is not limited to one pathway. You can inhale gases and tiny particles that re-release from surfaces. You can also absorb chemicals through skin contact with contaminated items, like couches, carpets, bedding, or clothes. For infants and young children who touch surfaces constantly and spend long periods indoors, that lingering exposure can be especially concerning.

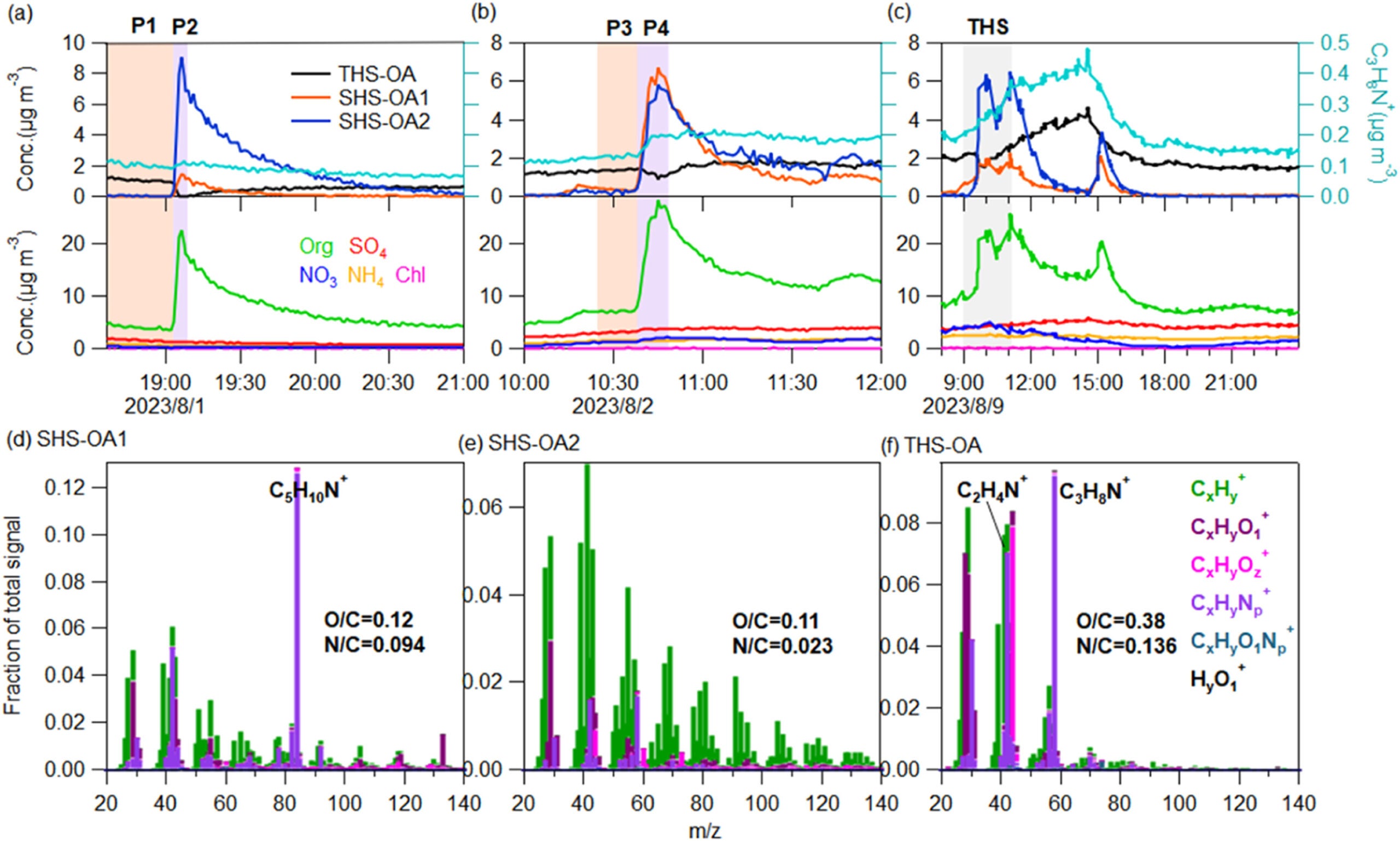

Instead of relying only on dust wipes and lab tests, the team watched thirdhand smoke evolve in real time. They monitored a lounge at the Tower Branch of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics for a month, from July 30 to Aug. 29, 2023. The lounge was about 360 cubic meters, with windows, central air conditioning, ventilation fans, and a plant area in the center. A 58-year-old manager who smokes worked there during daytime hours, smoking at times in a private office or in the lounge.

To separate indoor sources from outdoor pollution, the scientists alternated indoor and outdoor air sampling every 15 minutes. They used high-end aerosol instruments to track the chemistry of fine particles, including organic material and inorganic components like sulfate and nitrate.

With statistical source analysis, the team identified distinct “factors” tied to smoking. During clear secondhand smoke events, cigarette smoke produced strong spikes of organic particles, averaging about 25 micrograms per cubic meter. Two particle signatures were closely linked to active smoking, reflecting fresh smoke and early chemical “aging” as smoke mixed with indoor air.

The most striking finding came when nobody was actively smoking. The team captured a period where a smoker entered the lounge but did not smoke inside. Even so, a thirdhand smoke particle signature gradually built up, showing that residues carried on clothing and the room’s surfaces can become airborne again.

The thirdhand signature was chemically distinct from secondhand smoke, not just weaker. It showed stronger signals from nitrogen-containing fragments, which helped the researchers separate lingering residue from fresh smoke.

Across multiple periods, the team saw a steady thirdhand background of about 1 to 2 micrograms per cubic meter, even before obvious smoking events. That pattern points to a persistent baseline source: contaminated surfaces slowly releasing pollutants back into the air.

The researchers also flagged a modern twist. In the lounge, UV ozone disinfection was linked to added particle formation tied to thirdhand smoke. In other words, a method meant to sanitize air and surfaces could also help drive chemical reactions that turn tobacco residue into new airborne compounds.

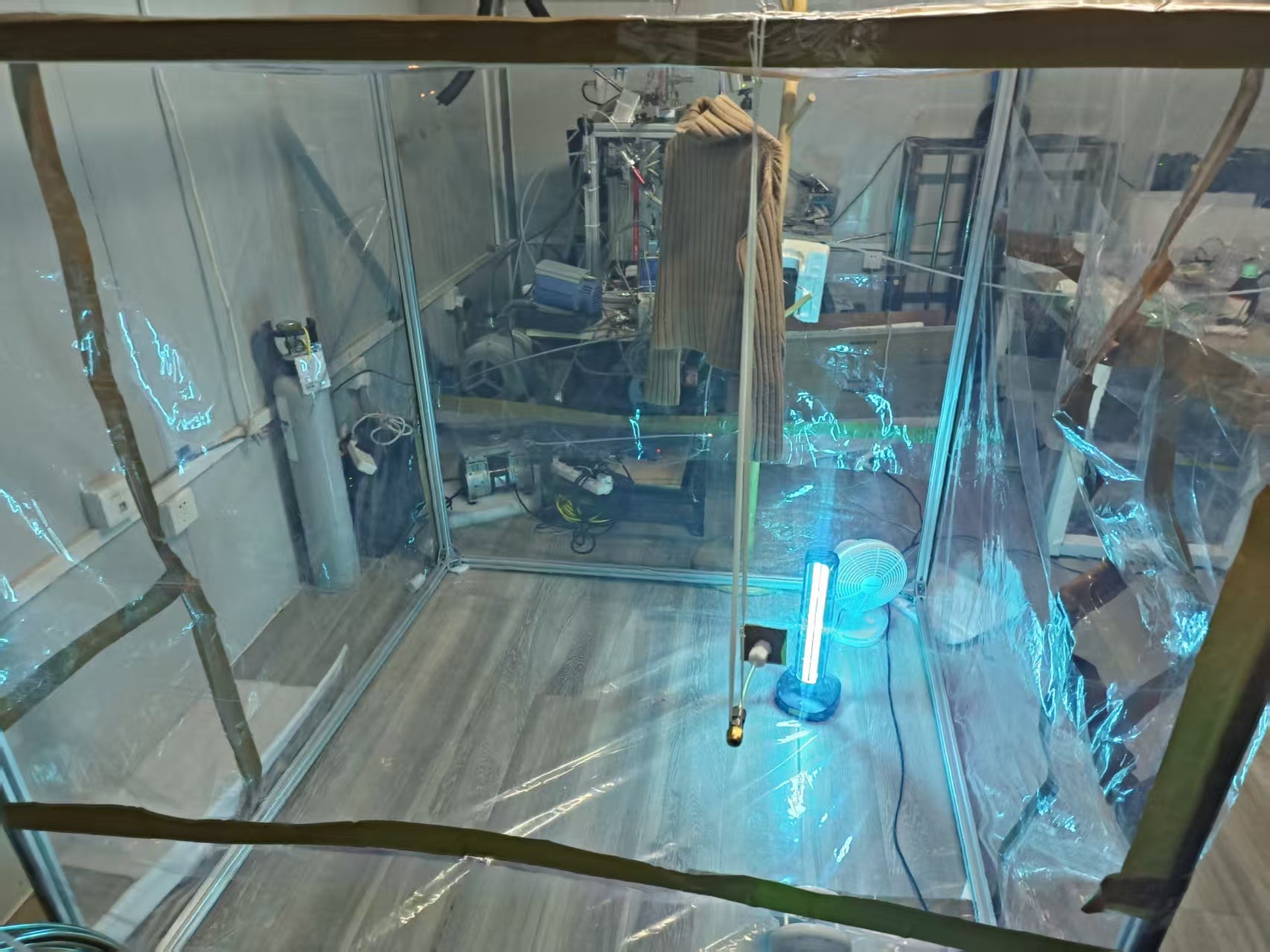

To understand the chemistry in more detail, the team built a sealed Teflon chamber in the lab and tracked gases in real time with two advanced mass spectrometers. They focused on volatile organic compounds, a broad class of gases that can irritate airways and also take part in indoor chemical reactions.

They used wool sweaters and cotton T-shirts as “carriers” for smoke residue. A “Nanjing” brand cigarette was burned near the fabric for different exposure times, from 30 minutes up to 24 hours. Then the contaminated clothing was placed in the chamber, and emissions were tracked for 15 hours.

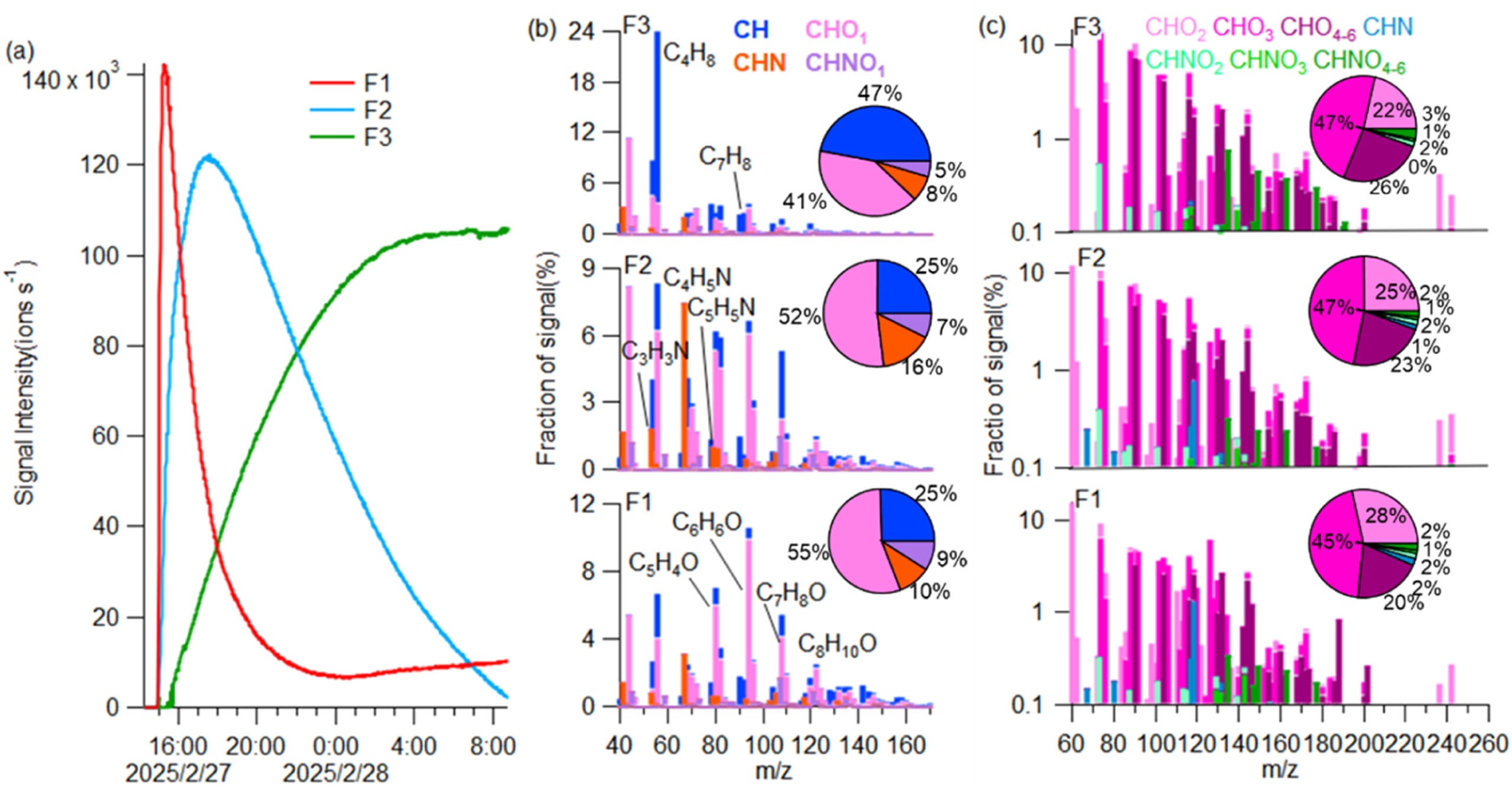

The instruments detected hundreds of organic molecules. Thirdhand smoke from clothing contained recognizable tracers, including 2-methylfuran, 2,5-dimethylfuran, phenol, toluene, pyrrole, and 3-ethenylpyridine. Many of the detected thirdhand compounds were relatively small oxygen-containing molecules. Nitrogen-containing compounds were also prominent, often with carbon counts in the mid range.

Secondhand smoke, by comparison, showed stronger nicotine-related signatures and a richer mix of larger, more oxygenated compounds. That difference helped reinforce a key point: thirdhand smoke is a different mixture, shaped by surface storage, slow release, and indoor chemistry.

When the team exposed contaminated clothing to ozone from a UV ozone lamp, the chemical blend shifted sharply. Ozone attacked certain bonds in molecules like furans and pyrroles and helped generate more oxygen-rich products. After oxidation, the mixture contained a much larger fraction of highly oxygenated compounds.

They also grouped gases by how easily they evaporate. Secondhand smoke leaned heavily toward intermediate-volatility compounds, while thirdhand smoke contained a higher share of true VOCs. After ozone treatment, the share of semi-volatile compounds rose substantially, helping explain why ozone disinfection in the real lounge could boost particle formation linked to tobacco residue.

Nicotine offered a simple example of persistence. In the chamber, secondhand smoke produced a quick, high nicotine level. Thirdhand emissions were lower, but they lasted far longer. During ozone exposure, nicotine disappeared within two hours, consistent with prior evidence that ozone can remove nicotine while producing oxidation byproducts.

The team also identified a three-phase release pattern from contaminated fabric: an early burst, a longer mid-stage dominated by nitrogen-containing compounds, and a slow tail that built over many hours. That long tail underlines why the smell may fade while chemical exposure continues.

These findings push you to think beyond the moment a cigarette goes out. The study suggests indoor exposure can continue through a stable background of thirdhand pollution, even when smoking is not happening. People who smoke can also act as moving sources, carrying residues on clothing, hair, and skin into offices, hallways, and other shared spaces.

For future research, the work offers clearer chemical markers that help distinguish thirdhand from secondhand smoke in real buildings. It also highlights how common indoor practices, like ozone-based disinfection, may unintentionally transform tobacco residues into new airborne chemicals. That insight can shape safer cleaning standards and better indoor air rules.

For everyday life, the message is practical. Ventilation matters, but materials matter too. Porous fabrics such as wool can store residues and release them slowly, so spaces used by children may benefit from easier-to-clean surfaces and furnishings that trap less residue. Dedicated smoking rooms also need independent exhaust systems, so contaminated air does not cycle back into the rest of a building.

Research findings are available online in the journal Building and Environment.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Thirdhand smoke: Hidden toxic residue from smoking lingers in homes for years appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.