When you look up at the night sky, planets seem calm and fixed. But a new study shows that nearby planetary systems can be violent and chaotic. Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers have watched the glowing aftermath of two massive collisions unfold around a nearby star.

The research team includes scientists from Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley. Among them is Jason Wang, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Northwestern, and Paul Kalas, an astronomer at UC Berkeley. Their findings will appear in the journal Science.

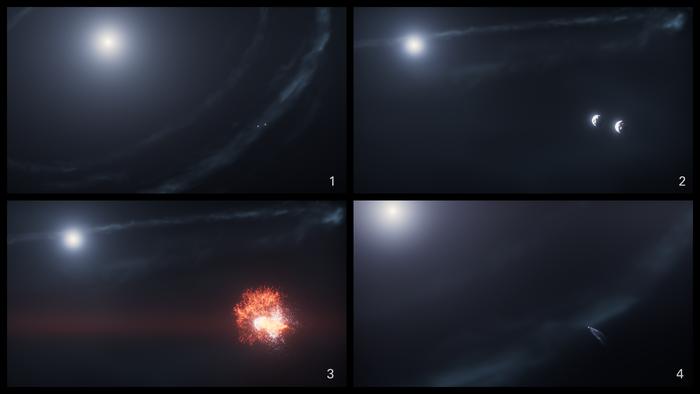

At first, astronomers thought they were watching an exoplanet. Instead, they realized they were seeing the dusty wreckage from two separate smashups between large rocky bodies. These events happened in real time, on astronomical scales, offering a rare window into how planets are built and destroyed.

The system centers on Fomalhaut, a bright star about 25 light-years from Earth. It is younger and more massive than the sun and surrounded by one of the largest known debris belts. Jason Wang has helped monitor this system for two decades.

“The system has one of the largest dust belts that we know of,” Wang said. “That makes it an easy target to study.”

In 2008, Hubble images revealed a faint point of light near the belt. Astronomers named it Fomalhaut b and proposed it was a planet reflecting starlight. The idea raised eyebrows because the object looked too bright and failed to appear in infrared data.

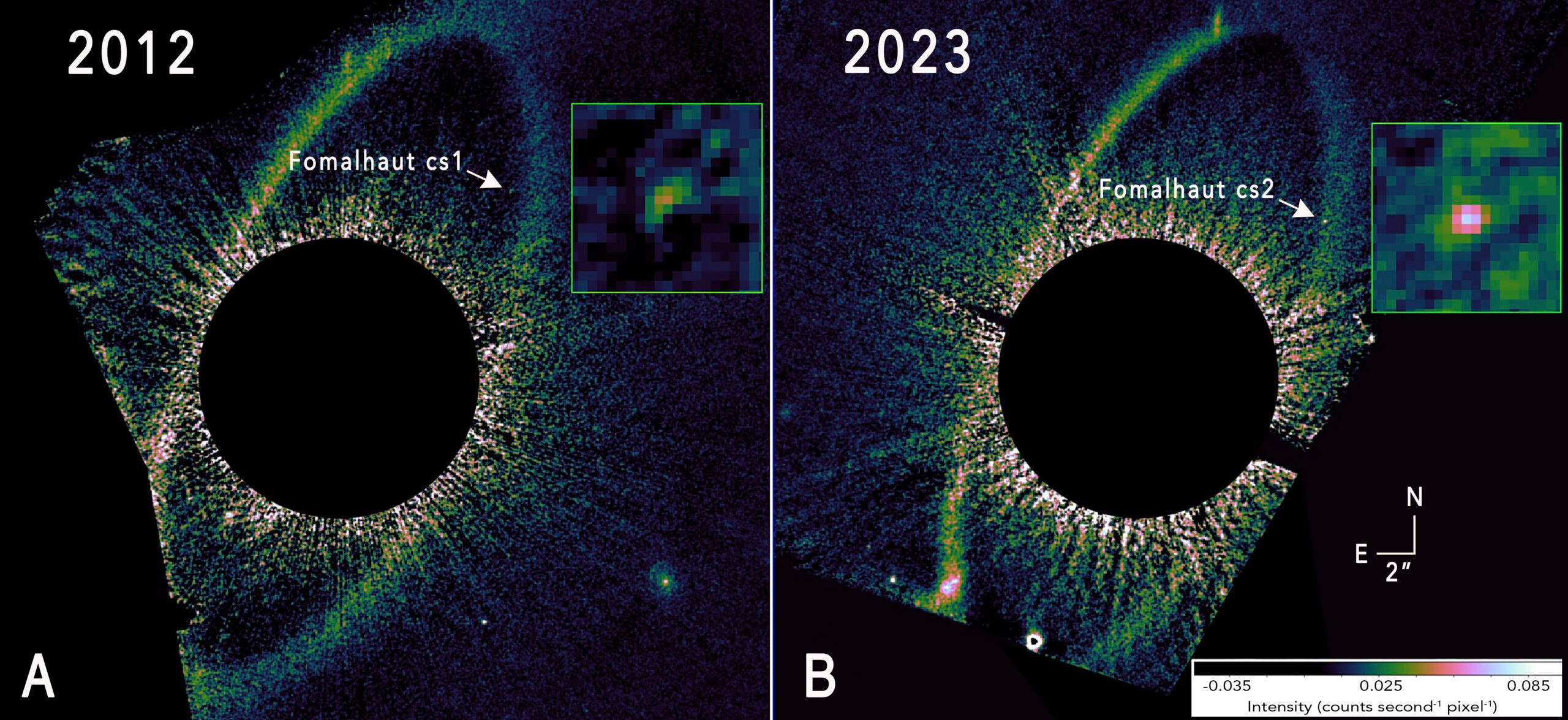

Years later, new observations deepened the mystery. The light source faded, grew larger, and then vanished. In 2023, when astronomers returned with Hubble, they found something unexpected. The original source was gone, but a new bright point appeared nearby.

“With these observations, our original intention was to monitor Fomalhaut b, which we initially thought was a planet,” Wang said. “We assumed the bright light was Fomalhaut b because that’s the known source in the system. But, upon carefully comparing our new images to past images, we realized it could not be the same source. That was both exciting and caused us to scratch our heads.”

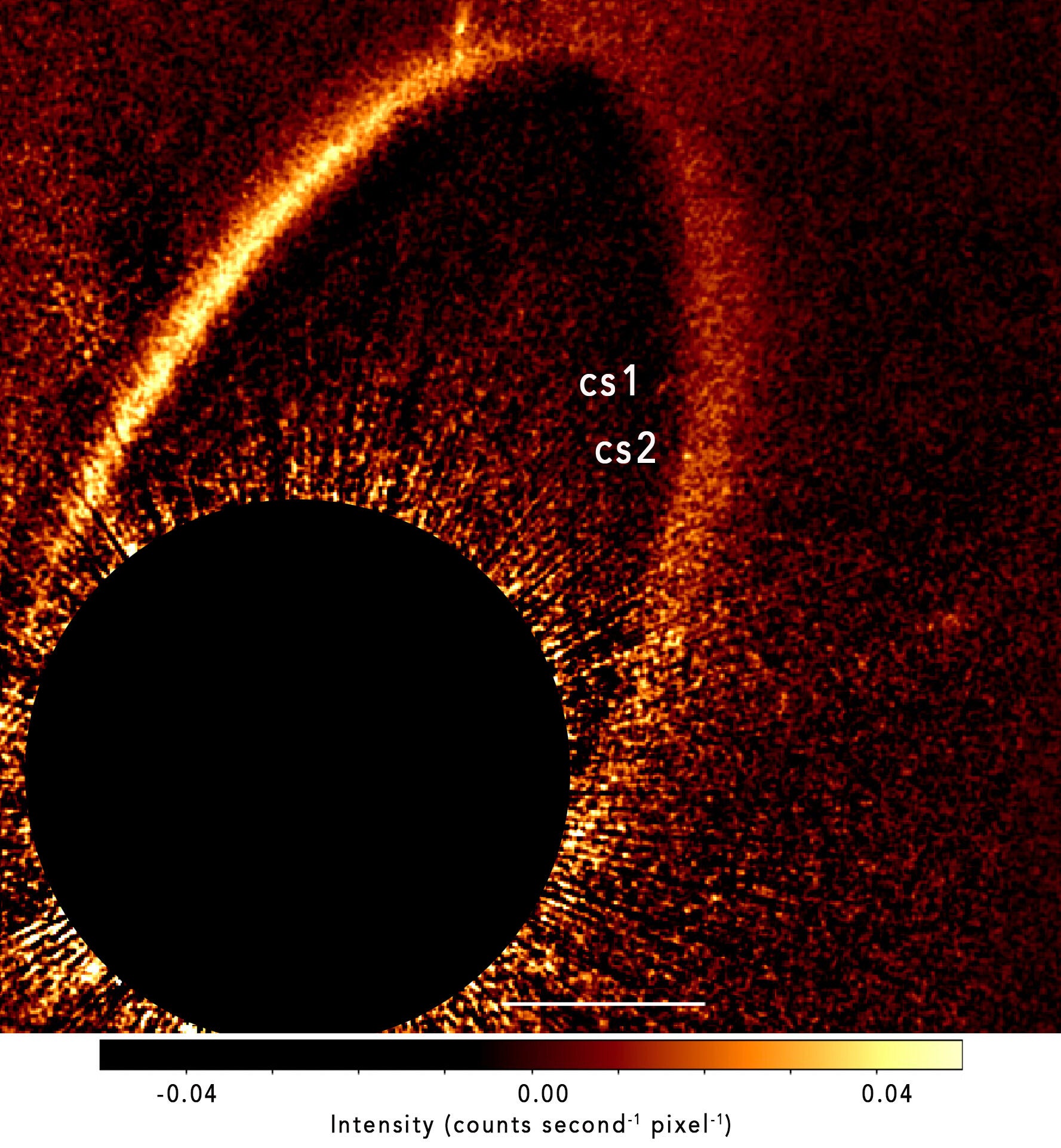

The team renamed the original object Fomalhaut cs1 and the new one Fomalhaut cs2. Their conclusion was striking. Neither source was a planet. Both were clouds of debris created when large planetesimals collided at high speed.

“These were not planets at all,” Kalas said. “This is certainly the first time I’ve ever seen a point of light appear out of nowhere in an exoplanetary system.”

The brightness and location of cs2 closely match how cs1 looked when it first appeared two decades earlier. That similarity suggested the same cause. Two violent collisions, spaced only about 20 years apart, occurred in the same debris belt.

Theory predicts such events should be rare, perhaps once every 100,000 years in a system like this. Seeing two within a human lifetime stunned the researchers.

“If you had a movie of the last 3,000 years, and it was sped up so that every year was a fraction of a second, imagine how many flashes you’d see,” Kalas said. “Fomalhaut’s planetary system would be sparkling with these collisions.”

To be sure, the team carried out four independent analyses of the Hubble data. Wang led one of them, checking the measurements and motion of the new source.

“This is the first time we’re seeing something like this,” Wang said. “So, we had to make sure we can trust our images and that we are measuring the properties of the collision properly.”

The data show cs1 moved outward at increasing speed before fading. That behavior matches what radiation pressure from the star would do to tiny dust grains. As the cloud expanded and thinned, sunlight pushed it apart faster, causing it to dim and spread until it disappeared.

Cs2 now sits near the inner edge of the debris belt. It shines even brighter than cs1 did late in its life, suggesting a fresh collision. Earlier Hubble images were sensitive enough to see it, yet showed nothing, ruling out a background star.

The brightness of these clouds reveals their scale. Cs1 required an enormous amount of dust, far more than seen after asteroid breakups in our own solar system. The calculations point to parent bodies roughly 30 kilometers across, similar in size to large asteroids.

Over hundreds of millions of years, repeated collisions like these help grind large bodies into dust. That process feeds debris belts and supplies the raw material that can clump together to form planets. Watching it happen elsewhere helps you understand how Earth and its neighbors once formed.

The clustering of the two collisions also raises questions. They occurred close together in space, not just in time. That pattern could be coincidence, but it might hint at unseen forces shaping where impacts happen, possibly from an undiscovered planet or a tilted inner belt.

The discovery carries an important lesson. Dust clouds from collisions can mimic planets for years. They reflect starlight and move with the star, just as a planet would.

“Fomalhaut cs2 looks exactly like an extrasolar planet reflecting starlight,” Kalas said. “What we learned from studying cs1 is that a large dust cloud can masquerade as a planet for many years. This is a cautionary note for future missions that aim to detect extrasolar planets in reflected light.”

As astronomers prepare to use powerful new telescopes, that warning matters. Misidentifying debris as a planet could skew estimates of how common Earth-like worlds really are.

“Although Hubble can no longer collect the most precise data, our team is not done. We have secured time on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, using its Near-Infrared Camera to study cs2,” Wang shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“Due to Hubble’s age, it can no longer collect reliable data of the system,” he continued. “Fortunately, we now have the JWST.”

Webb’s instruments can reveal the color, size, and makeup of the dust grains. That information may show whether the debris contains ice or water-rich material, clues that matter for understanding habitable worlds.

This research reshapes how you interpret distant planetary systems. It shows that violent collisions can light up debris belts and fool even experienced observers. By learning how these dust clouds behave, astronomers can avoid false planet detections and refine future surveys.

The findings also deepen knowledge of planet formation. Watching collisions in real time provides evidence of how rocky bodies grow, shatter, and recycle material. That insight helps scientists model the early history of our own solar system.

Beyond astronomy, the work informs planetary defense. Understanding how asteroids break apart, and how much debris they produce, supports efforts like NASA’s asteroid redirection tests. In the long run, that knowledge can help protect Earth.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Two collisions, one star, and a new view of planet formation appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.