Around 5,000 years ago, people in what is now Iran began turning dull stone into shining metal. By heating copper ore until it melted, they learned to pull liquid metal from rock, a skill that helped launch the age of metallurgy and changed daily life, from tools and weapons to jewelry and trade.

Today, scientists are trying to understand exactly how those early metalworkers did it, even though most of their furnaces and tools have vanished. A new study from MIT offers a fresh way to see into that distant past, using a technology more often found in hospitals than in dig sites.

The research looks at copper smelting waste from Tepe Hissar, an important archaeological site in Iran that dates to roughly 3100 to 2900 BCE. At that time, people in the region were already running complex settlements with long distance trade and early metal industries.

Instead of studying rare finished objects, the team focused on slag, the hard, glassy waste left over after ore is melted. Slag may look like trash, but it carries a record of the smelting process inside it.

“Even though slag might not give us the complete picture, it tells stories of how past civilizations were able to refine raw materials from ore and then to metal,” says MIT postdoc Benjamin Sabatini. “The goal is to understand, from start to finish, how they accomplished making these shiny metal products.”

For you, that means the same lump of waste that ancient workers tossed aside can now help reveal how they mastered one of humanity’s first high tech skills.

When ore is heated to smelting temperatures, it separates into dense metal and a lighter molten waste. The metal pools at the bottom; the slag floats above it and later cools into a solid block. That solid includes leftover minerals from the ore, bits of furnace lining, trapped gas bubbles, and tiny droplets of metal.

In early copper smelting, those mineral leftovers often contained arsenic and other elements that shape how the metal behaves. Over thousands of years, however, rain, soil water, and chemical reactions can leach those elements out or move them around. That makes it hard for archaeologists to read slag like a clean notebook.

“Slag waste is chemically complex to interpret because in our modern metallurgical practices it contains everything not desired in the final product, in particular, arsenic,” says senior author Antoine Allanore, professor of metallurgy and director of MIT’s Center for Materials Research in Archaeology and Ethnology. “The challenge here is that these minerals, especially arsenic, are very prone to dissolution and leaching.”

So if you slice a piece of slag at random, you may miss the most useful clues or mistake weathered material for original features.

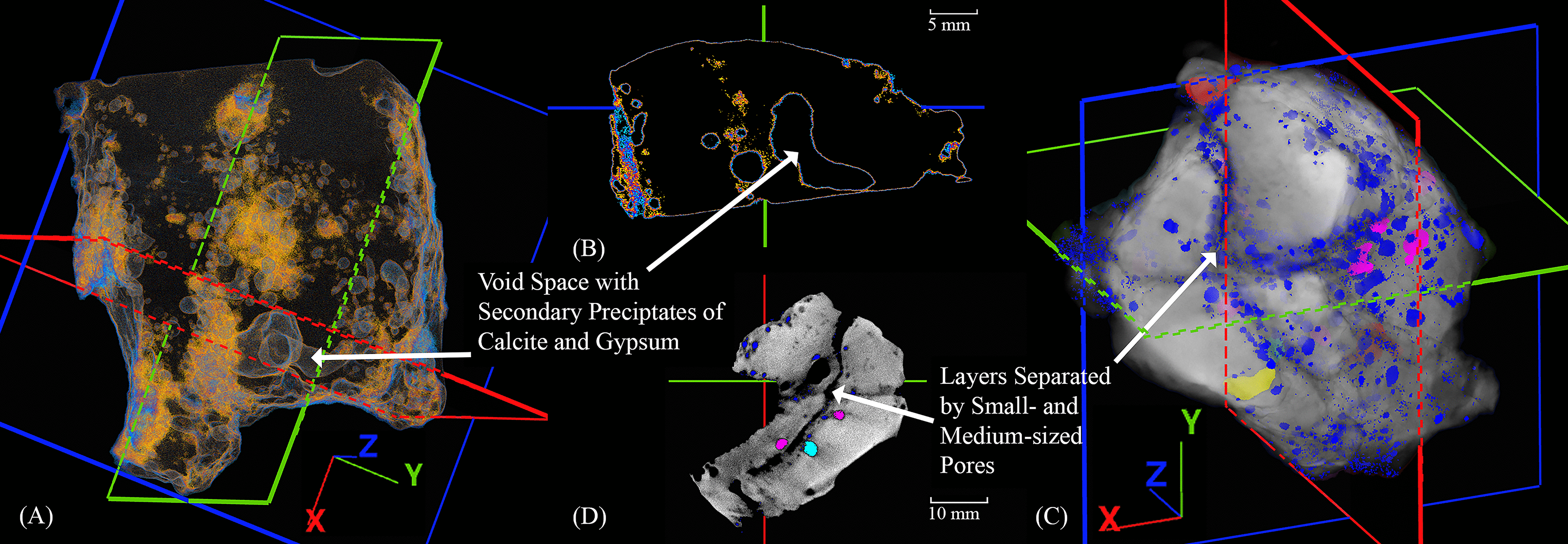

To get around that problem, the MIT team borrowed a tool from medicine: X ray computed tomography, better known as CT scanning. Instead of scanning a human chest or brain, they scanned fist sized chunks of slag on campus and at an industrial CT facility in Cambridge.

A CT scanner takes hundreds or thousands of X ray images from different angles, then combines them into a three dimensional view of the object’s interior. Dense materials, such as metal droplets, absorb more X rays and show up as bright spots; pores and low density glass appear darker.

“The CT scan approach is a transformation of traditional archaeological methods of determining how to make cuts and analyze samples,” Allanore says.

![Two-dimensional and 3D images of slags -S37A [(A), (B)] and H76-S45B [(C), (D)], respectively, showing the slice planes in software before sectioning.](https://www.thebrighterside.news/uploads/2025/11/ct-4.png?auto=webp)

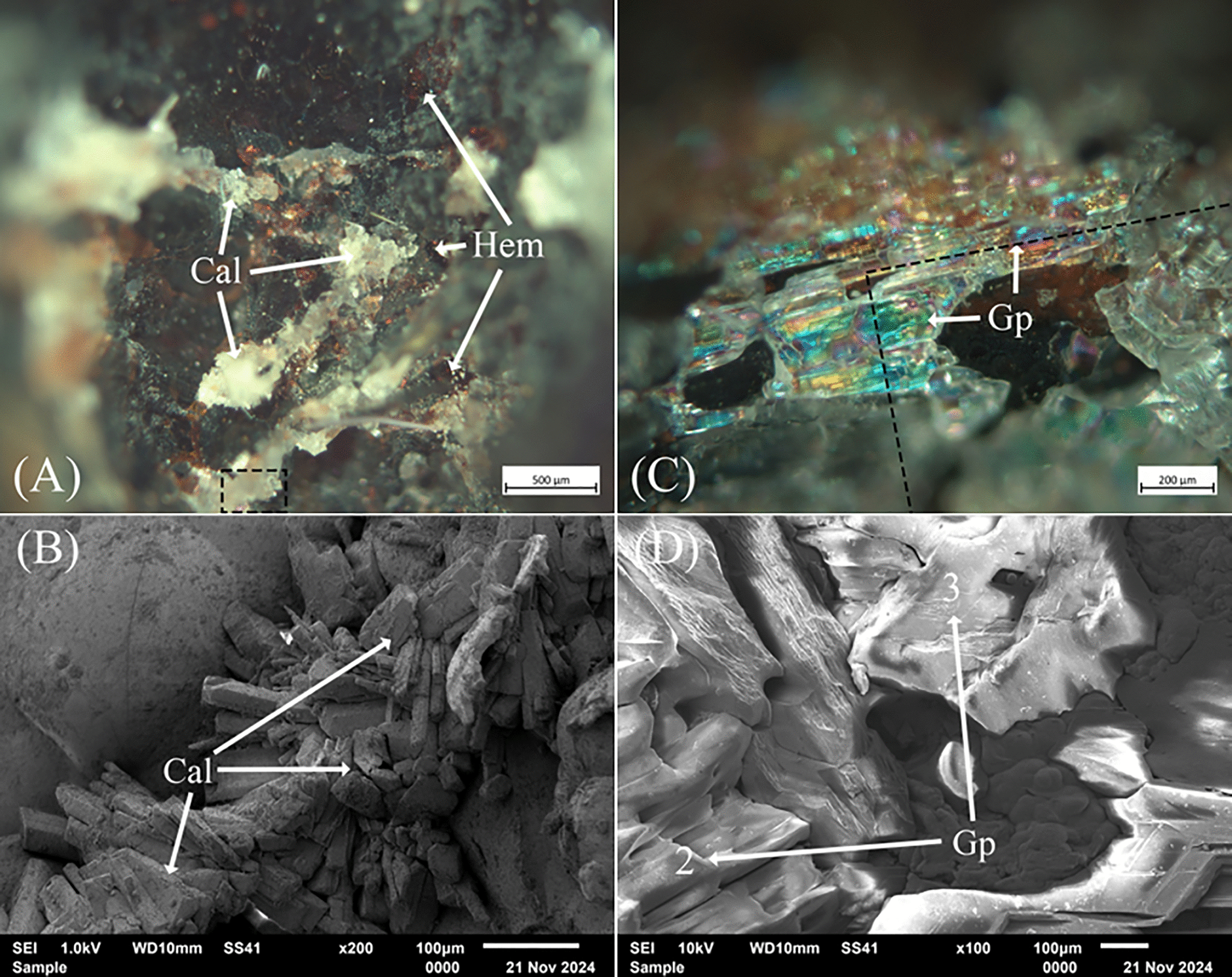

After the scans, the researchers used more familiar tools: X ray fluorescence to measure surface chemistry, X ray diffraction to identify minerals, and optical and scanning electron microscopes to study polished slices. The CT images guided where to make those slices, so each cut passed through the most informative zones.

The slag samples came from the Penn Museum, which loaned material from Tepe Hissar to Allanore’s lab in 2022. Some pieces looked rough and porous, with green corrosion stains; others appeared dense and smooth.

“CT scans showed that outward appearance could be misleading. The rough pieces were riddled with large voids and pockets; the dense piece also held hidden cavities and inclusions the naked eye could not see. High density spots turned out to be tiny droplets of copper rich metal that had not fully separated during smelting,” Sabatini told The Brighter Side of News.

“My strategy was to zero in on the high density metal droplets that looked like they were still intact, since those might be most representative of the original process,” Sabatini continued. “The CT scanning shows you exactly what is most interesting, as well as the general layout of things you need to study.”

For you, that means scientists can now choose a single precise slice that crosses metal droplets, gas bubbles, and layered slag, instead of grinding up large chunks and hoping for the best.

![Two-dimensional and 3D images of slags -S37A [(A), (B)] and H76-S45B [(C), (D)], respectively, showing internal metal droplets.](https://www.thebrighterside.news/uploads/2025/11/ct-5.png?auto=webp)

Earlier work at Tepe Hissar had found arsenic bearing compounds in some slag, raising questions about whether ancient craftsmen were trying to make arsenical copper, an early type of bronze. Some scholars saw that as proof of deliberate alloying; others argued it might be a side effect of the ores used.

The new study shows that arsenic does not sit still inside slag. The researchers found it in different mineral phases and saw signs that it could move within the slag or even escape over time. That means a simple “yes or no” test for arsenic cannot tell you exactly how the smelting was done.

By mapping pores and corrosion paths, the CT based method also highlights where weathering may have changed the chemistry most. That helps you separate features linked to the original furnace from changes that happened during 5,000 years in the ground.

“The Early Bronze Age is one of the earliest reported interactions between mankind and metals,” Allanore says. “This should be an important lever for more systematic studies of the copper aspect of smelting, and also for continuing to understand the role of arsenic.”

For museums and excavation teams, slag is often abundant but poorly understood. It is heavy, irregular, and easy to overlook next to ornate finished artifacts. The MIT work suggests that slag deserves more attention, and that CT scanning can stretch each sample further.

Because CT is noninvasive, curators can preserve rare pieces while still sharing high resolution 3D data with scholars around the world. Researchers can then plan a small number of targeted cuts, getting more information from less damage.

At the same time, the approach creates a bridge between modern materials science and archaeology. The same methods used to understand advanced alloys and industrial slags can now help you reconstruct the first metal furnaces humans ever built.

“It allows us to be cognizant of the role of corrosion and the long term stability of the artifacts to continue to learn more,” Allanore says. “It will be a key support for people who want to investigate these questions.”

This work gives archaeologists a powerful new way to read the technological skills of early societies without destroying rare materials. CT guided analysis can reveal how hot ancient furnaces ran, how well metal separated from slag, and how workers managed impurities such as arsenic. That helps you trace when and where more advanced metallurgical methods first appeared.

For materials scientists and engineers, the study shows how ancient slags can act as natural experiments in long term corrosion and phase stability. Lessons from 5,000 year old waste could inform modern strategies for handling toxic elements and designing more durable industrial byproducts.

For museums and heritage institutions, CT scanning offers a path to balance preservation with research. Digital 3D records can be shared widely, while physical pieces stay safe. Over time, a global library of scanned artifacts could let researchers compare early metallurgical techniques across regions and cultures, deepening our shared understanding of how metal working spread and evolved.

In the long run, that kind of knowledge helps humanity tell a more complete story about its own creativity, from the first copper smelters at Tepe Hissar to the complex materials used in today’s technology.

Research findings are available online in the journal PLOS One.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post MIT study uses medical CT imaging to reconstruct 5,000 year-old metal production appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.