An international team of astronomers, working with researchers from University College Dublin and other institutions, has detected a supernova from an era once thought far beyond reach. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, the team observed the explosive death of a massive star that occurred when the universe was only about 730 million years old.

The discovery followed a powerful flash of radiation known as GRB 250314A, detected on March 14, 2025, by the SVOM satellite. That signal marked a long-duration gamma-ray burst, a type closely linked to the collapse of massive stars. Follow-up measurements from the European Southern Observatory using the Very Large Telescope confirmed the event’s extreme distance, placing it deep in the era of cosmic reionization.

The results are detailed in a study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Together, the observations offer the clearest view yet of a single star’s death during the universe’s early growth.

Understanding the first generations of stars remains one of cosmology’s central challenges. These early giants likely drove cosmic reionization and seeded space with the first heavy elements. Yet most knowledge of them comes from blended light across entire galaxies, not from individual stars.

Gamma-ray bursts offer a rare exception. Because they are so bright, they can be seen across vast distances. Most long-duration bursts arise from collapsing massive stars, making them natural markers of stellar death in the early universe. Until now, however, supernovae tied to such bursts had only been confirmed much closer to home.

GRB 250314A changed that picture. Its redshift of about 7.3 places it among the most distant stellar explosions ever studied. Catching its associated supernova offered a direct test of whether stars in the young universe died in ways similar to those seen today.

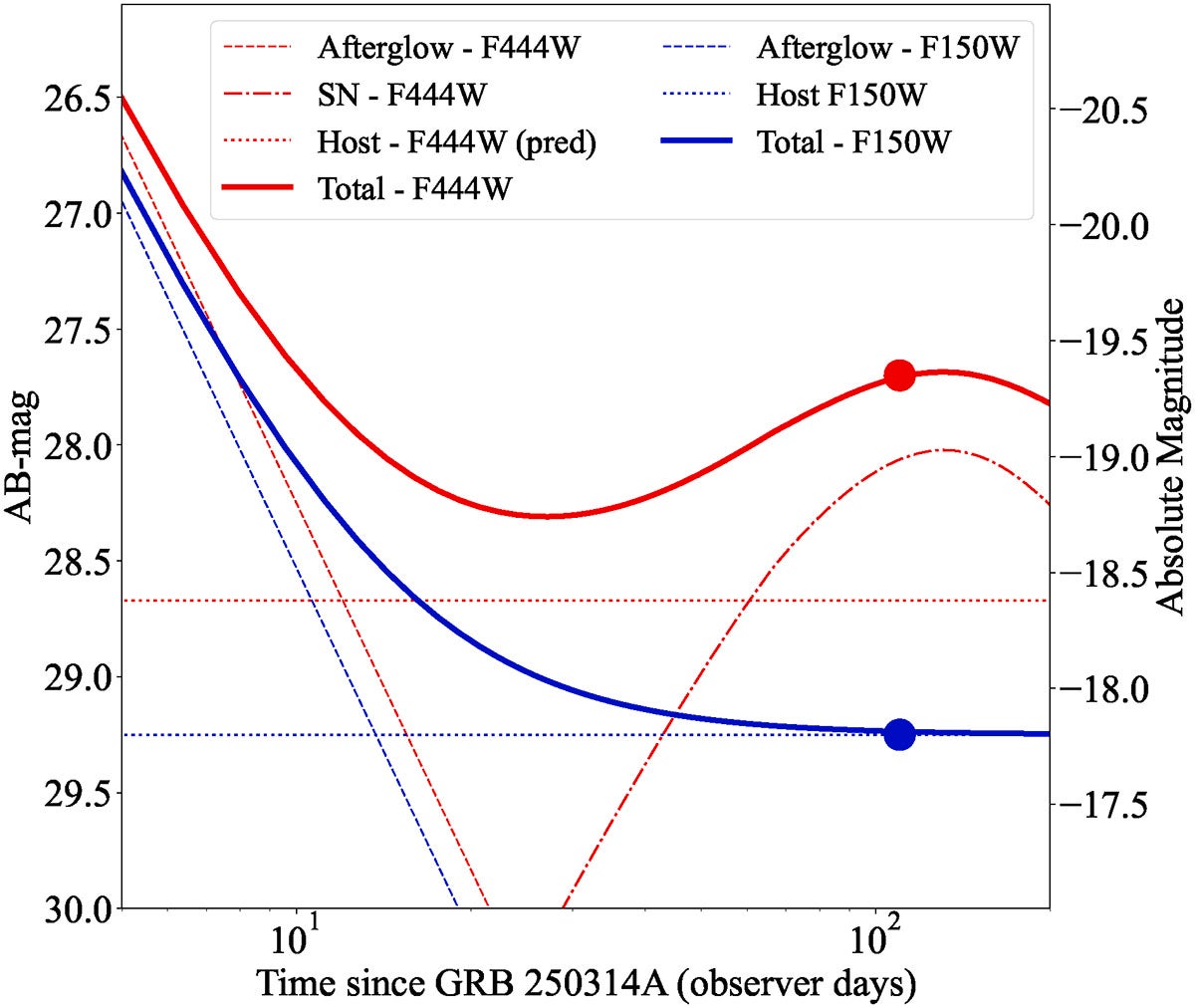

The decisive evidence came from JWST’s Near-Infrared Camera, which observed the burst site about 110 days after the initial explosion. At that point, the afterglow from the gamma-ray burst should have faded almost completely.

Instead, JWST detected faint but telling light. The signal appeared only in redder filters, with little or no emission at shorter wavelengths. That pattern matched expectations for a supernova rather than lingering afterglow or simple galaxy light.

Dr. Antonio Martin-Carrillo, an astrophysicist at University College Dublin’s School of Physics and a co-author on the study, said the finding linked gamma-ray bursts and stellar deaths at an unprecedented distance.

“The key observation, or smoking gun, that connects the death of massive stars with gamma-ray bursts is the discovery of a supernova emerging at the same sky location,” he said. “Almost every supernova ever studied has been relatively nearby to us, with just a handful of exceptions to date.”

When the team confirmed the age of the event, they recognized a rare chance to study how stars formed and died when the universe was still young.

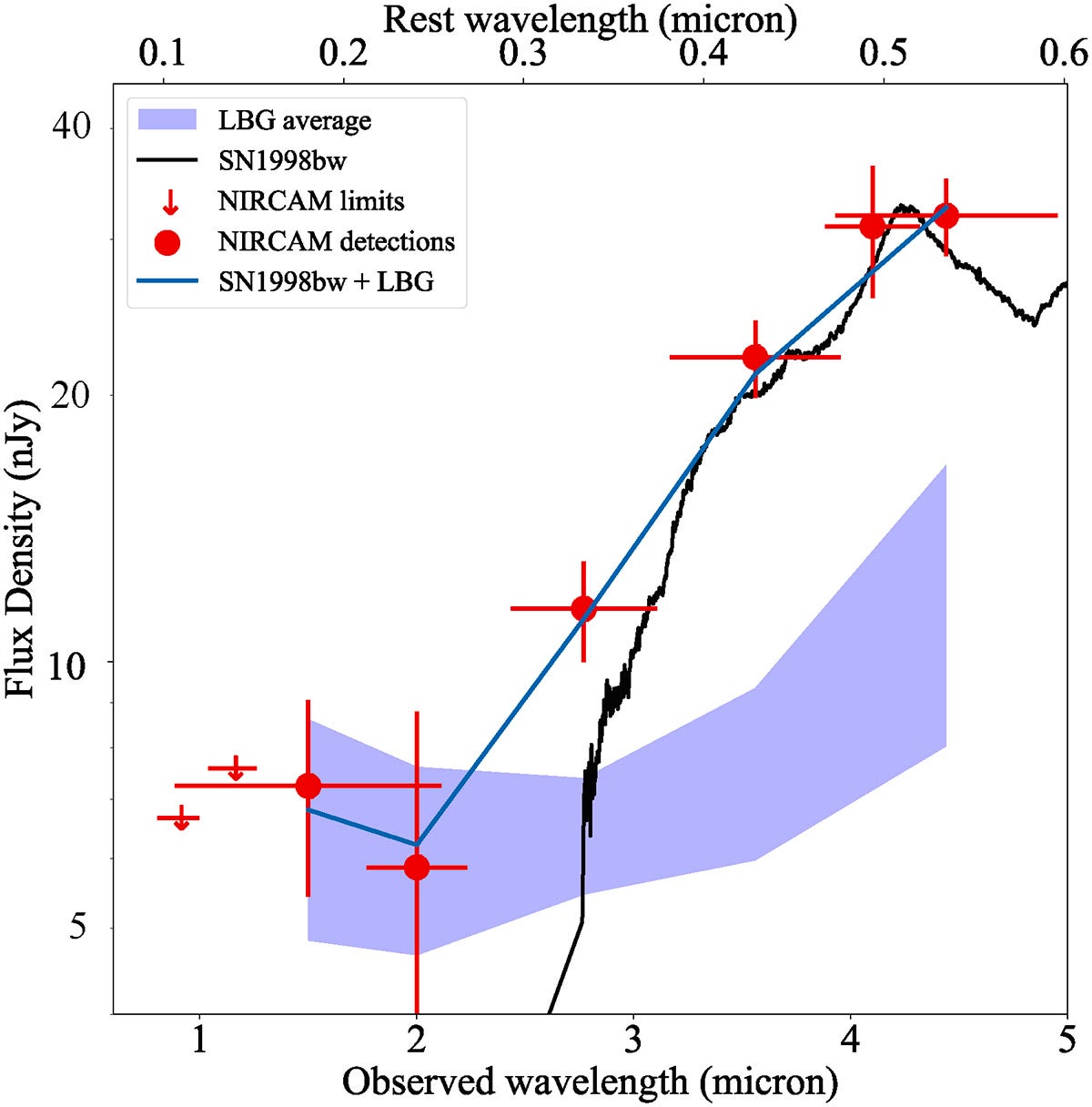

To interpret the data, researchers compared the observed light with models based on known supernovae linked to gamma-ray bursts in the nearby universe. One benchmark was SN 1998bw, a well-studied explosion that has become a standard reference.

The match surprised them. Despite the early universe’s lower metal content and harsher conditions, the distant supernova showed similar brightness and spectral behavior to SN 1998bw. It did not appear unusually bright or blue, traits some theories predict for early stellar explosions.

“Using models based on the population of supernovae associated with GRBs in our local universe, we made some predictions of what the emission should be and used it to propose a new observation with the James Webb Space Telescope,” Martin-Carrillo said. “To our surprise, our model worked remarkably well and the observed supernova seems to match really well the death of stars that we see regularly.”

The data also ruled out more extreme events, such as superluminous supernovae. Instead, the explosion appeared ordinary in the best possible way.

The team explored whether the detected light could come from something else. A brighter-than-expected afterglow did not fit the known fading pattern of the burst. A host galaxy alone also failed to explain the observations without requiring unusual and unlikely properties.

The simplest explanation remained a combination of a faint young galaxy and a supernova similar to those seen billions of years later. That conclusion strengthens the case that at least some early massive stars followed familiar paths at the end of their lives.

“Our team plans to observe the site again with JWST in one to two years. By then, the supernova should have faded by more than two magnitudes. Measuring that decline will help separate the remaining galaxy light from the dying star’s last glow,” Martin-Carrillo shared with The Brighter Side of News.

For now, GRB 250314A stands as one of the earliest direct views of a stellar death. It shows that even in the universe’s youth, some cosmic events unfolded in ways you might recognize today.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post JWST detected a supernova from the dawn of the universe appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.