Surprised astronomers just discovered a world that blurs the line between planet and stellar remnant, hiding in a system known as a “black widow.”

Using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, researchers at the University of Chicago, Stanford University and the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory in Washington studied a Jupiter-mass companion circling a millisecond pulsar, PSR J2322–2650. What they found was a chemical outlier, with an atmosphere dominated by helium and molecular carbon chains that almost never survive in a typical planet’s air.

“This was an absolute surprise,” said study co-author Peter Gao of the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory in Washington. “I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was ‘What the heck is this?’ It’s extremely different from what we expected.”

The results, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, describe PSR J2322–2650b as a world with soot-like clouds and carbon chemistry so extreme that researchers think carbon could condense deep inside and form diamonds. The biggest puzzle is not what Webb saw. It is how this object formed at all.

A pulsar is a rapidly spinning neutron star that sweeps beams of radiation through space like a lighthouse. In this system, the pulsar is roughly Sun-like in mass, but city-sized in diameter. It also emits much of its power at high energies, including gamma rays. That matters for Webb. Those wavelengths do not flood Webb’s infrared instruments, so the companion can be studied without the usual stellar glare.

“This system is unique because we can view the planet illuminated by its host star, but not see the host star at all,” said Maya Beleznay, a third-year PhD candidate at Stanford University in California who worked on modeling the shape of the planet and the geometry of its orbit. “So we get a really pristine spectrum. And we can study this system in more detail than normal exoplanets.”

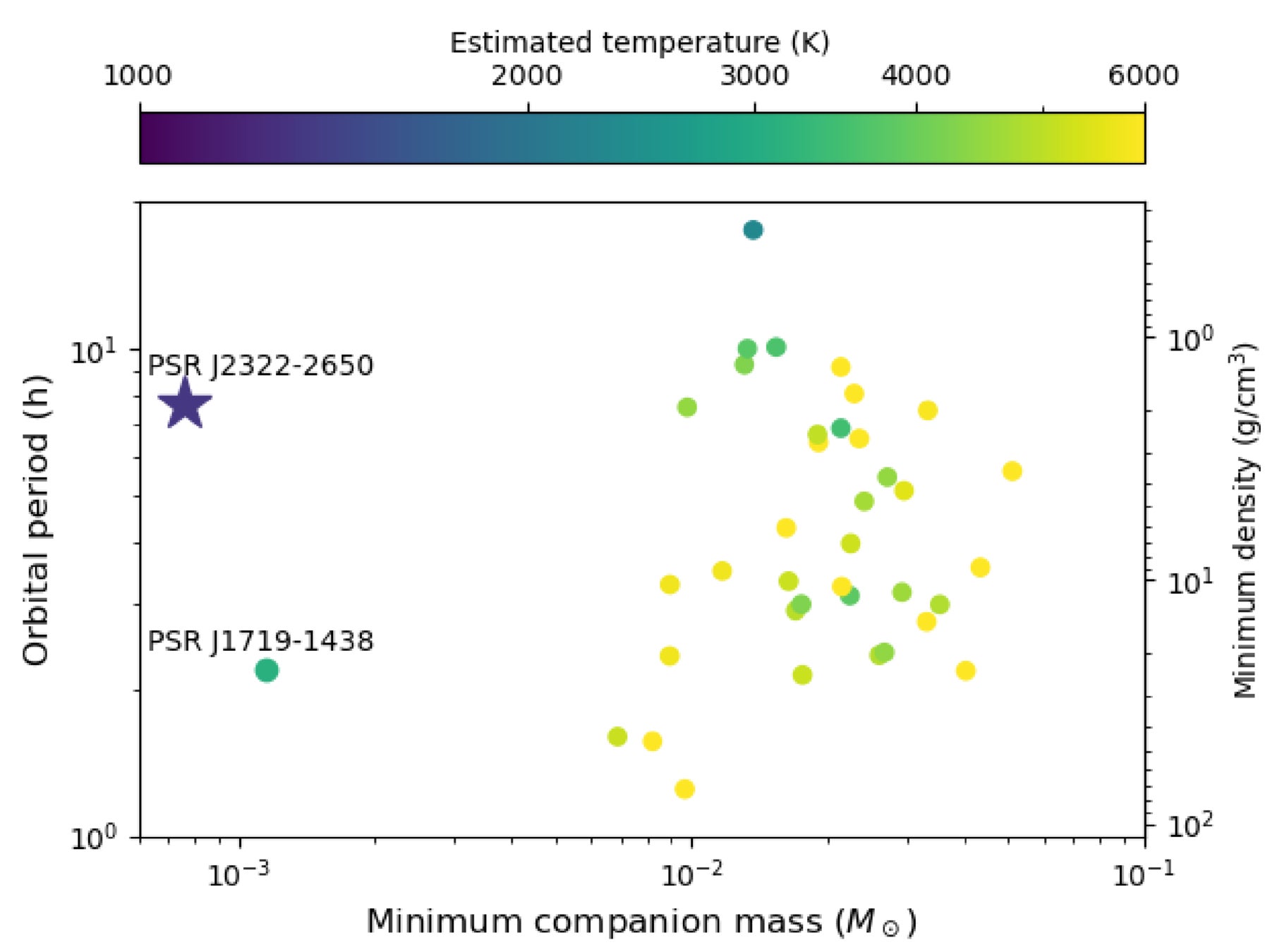

The companion sits shockingly close to the pulsar, about 1 million miles away. Earth sits about 100 million miles from the Sun. At that distance, PSR J2322–2650b completes an orbit in only 7.8 hours. The pulsar’s gravity likely stretches it into a lemon-like shape, close to filling its Roche lobe, the region where the pulsar’s pull can start to strip material away.

You can think of this pair as related to a “black widow” system, but with a key difference. In classic black widows, a millisecond pulsar orbits a low-mass stellar companion that it slowly erodes. Long ago, the pulsar likely stole gas from its partner and spun up. Now its wind and radiation help evaporate what is left.

Here, the companion falls below the 13-Jupiter-mass threshold that the International Astronomical Union uses to separate planets from heavier objects. That makes PSR J2322–2650b an “exoplanet” by mass, even if its history may not look like a normal planet’s origin story. Among thousands of known exoplanets, it stands out as the only hot Jupiter-like object known to orbit a pulsar.

“The planet orbits a star that’s completely bizarre — the mass of the Sun, but the size of a city,” said the University of Chicago’s Michael Zhang, the principal investigator on this study. “This is a new type of planet atmosphere that nobody has ever seen before. Instead of finding the normal molecules we expect to see on an exoplanet — like water, methane, and carbon dioxide — we saw molecular carbon, specifically C3 and C2.”

That detail is the heart of the mystery. At the temperatures involved, carbon usually bonds with oxygen, hydrogen, or nitrogen to form familiar molecules. Yet the dayside spectrum shows carbon chains, a sign that the atmosphere has almost no oxygen or nitrogen, and very little hydrogen.

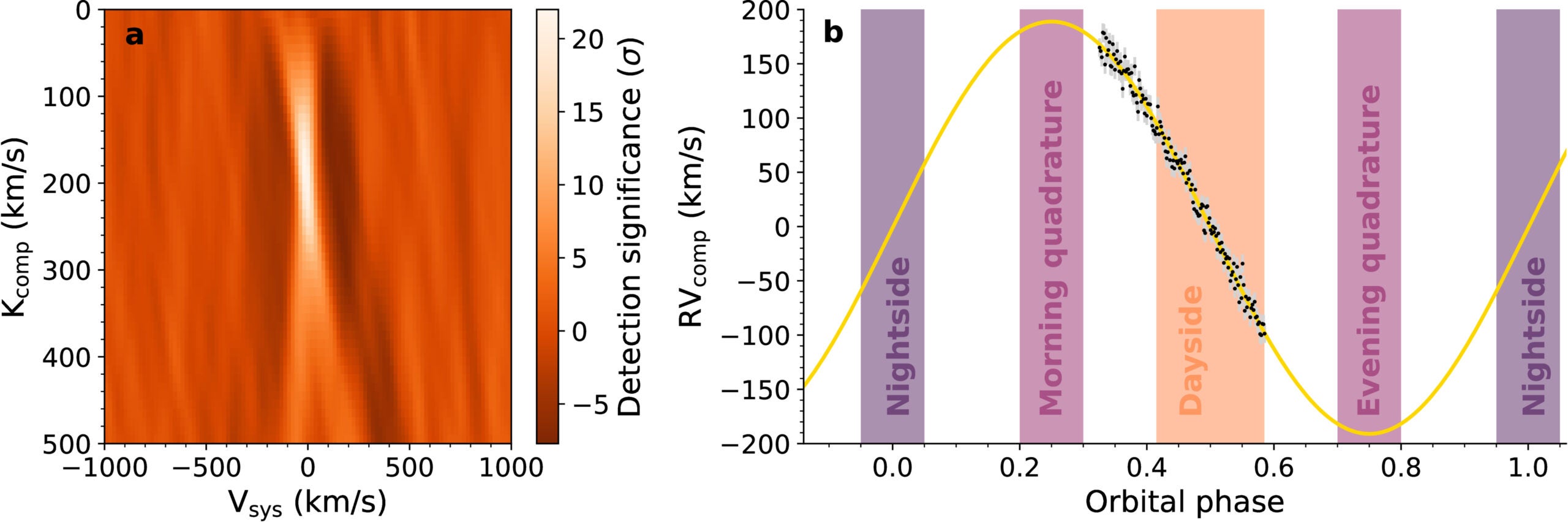

To map this world, the team used Webb’s NIRSpec instrument to collect infrared spectra over a full orbit. On Nov. 8, 2024, they recorded light from about 0.6 to 5.3 micrometers across the complete 7.8-hour cycle, from the cooler nightside to the hotter dayside and back. Two days later, they took higher-resolution measurements from 1.7 to 3.1 micrometers during a two-hour window, when the heated face pointed most directly toward Earth.

Those data let you see both temperature changes and chemistry. The nightside looks nearly featureless, which is consistent with thick dust or clouds that blur spectral lines. The dayside shows deep absorption features. By tracking how those features shift during the orbit, the team also measured how fast the companion moves and constrained its mass and the tilt of its orbit. Their analysis points to an inclination near 30 degrees and a companion mass roughly in the 1.4 to 2.4 Jupiter-mass range, with a radius close to Jupiter’s.

Temperature estimates vary across the surface. The companion appears to range from about 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit on the coldest parts of the nightside to about 3,700 degrees Fahrenheit at the hottest points of the dayside.

“The chemistry is what forces you to rethink the object’s past. Our team discovered firm detections of C₃ and C₂, carbon chains that produce distinctive infrared patterns. We also searched for many other species and found no strong signs of common molecules such as water or methane. Their limits suggest an atmosphere rich in carbon but poor in oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen,” Gao explained to The Brighter Side of News.

That creates a second challenge. A body made of carbon all the way through would be too compact to match the inferred size, unless it had an unrealistically hot interior. The researchers argue instead for a helium-dominated bulk composition, with carbon enrichment concentrated in the atmosphere and upper layers. They used chemistry and atmospheric models to show how carbon-rich gas, plus graphite-like dust, can reproduce the main shapes of the spectra, especially the muted nightside.

The light curve also hints at unusual winds. The hottest region appears shifted slightly west of where simple heating would place it. In other words, the atmosphere may push heat backward relative to the direction of rotation, a pattern seen in some black widow companions and expected in extremely fast, tidally locked objects.

Even with these clues, the origin story does not land cleanly on any known path.

“Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different,” said Zhang. “Did it form by stripping the outside of a star, like ‘normal’ black widow systems are formed? Probably not, because nuclear physics does not make pure carbon. It’s very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition. It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism.”

Study co-author Roger Romani, of Stanford University and the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology Institute, offered one possible way to build a carbon-rich atmosphere from inside out.

“As the companion cools down, the mixture of carbon and oxygen in the interior starts to crystallize,” said Romani. “Pure carbon crystals float to the top and get mixed into the helium, and that’s what we see. But then something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away. And that’s where the mystery comes in.

“But it’s nice to not know everything,” said Romani. “I’m looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere. It’s great to have a puzzle to go after.”

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post JWST spots a lemon-shaped exoplanet orbiting a pulsar — rewriting the rules of planet formation appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.