When scientists describe “Earth-like” planets, the phrase often brings to mind worlds scattered across the galaxy, quietly waiting to host oceans, forests, and perhaps civilizations. A recent scientific discussion suggests that this picture may be far too generous. In a SETI Live event hosted by the Carl Sagan Center, there was a more restrained view of habitability from researchers who argue that the physical and chemical requirements for complex or technological life are exceptionally strict.

The discussion featured Dr. Simon Steel, deputy director of the Carl Sagan Center, in conversation with Dr. Manuel Scherf and Dr. Helmut Lammer, both researchers at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Together, they examined how planetary atmospheres, stellar radiation, and long-term evolution shape the prospects for intelligent life. Their conclusion was direct. If advanced life needs conditions similar to those on Earth, then such planets may be rare in the Milky Way.

From the outset, the researchers urged you to rethink what “habitable” really means. Distance from a star alone is not enough. Instead, the atmosphere, the host star’s behavior, and a planet’s geological history all matter, often in ways that sharply narrow the field.

At the center of the discussion is Earth’s atmosphere, which the researchers described as unusual rather than typical. As Dr. Scherf explained, Earth’s blend of nitrogen, oxygen, and relatively low carbon dioxide reflects a long-lasting and finely tuned chemical balance. This balance supports large, energy-demanding organisms and allows complex ecosystems to persist.

Oxygen plays a key role. It acts as a powerful electron acceptor, making high-energy metabolism possible. To sustain organisms large enough to use tools or build technology, oxygen must reach partial pressures of about 100 millibars. Below that level, available energy drops. Life may still exist, but it is likely limited to microbes or very simple forms.

High oxygen levels bring problems too. If oxygen rises much above roughly 300 millibars, the planet becomes a fire risk on a global scale. A single ignition source could spread combustion across continents. In such conditions, forests, ecosystems, and early technologies would struggle to survive.

Carbon dioxide imposes its own limits. Too much carbon dioxide becomes toxic for animals and can destabilize climate systems. Too little weakens the upper atmosphere and disrupts long-term carbon cycling. That cycling helps regulate surface temperatures over millions of years. When it breaks down, planets can spiral into runaway heating or deep freeze.

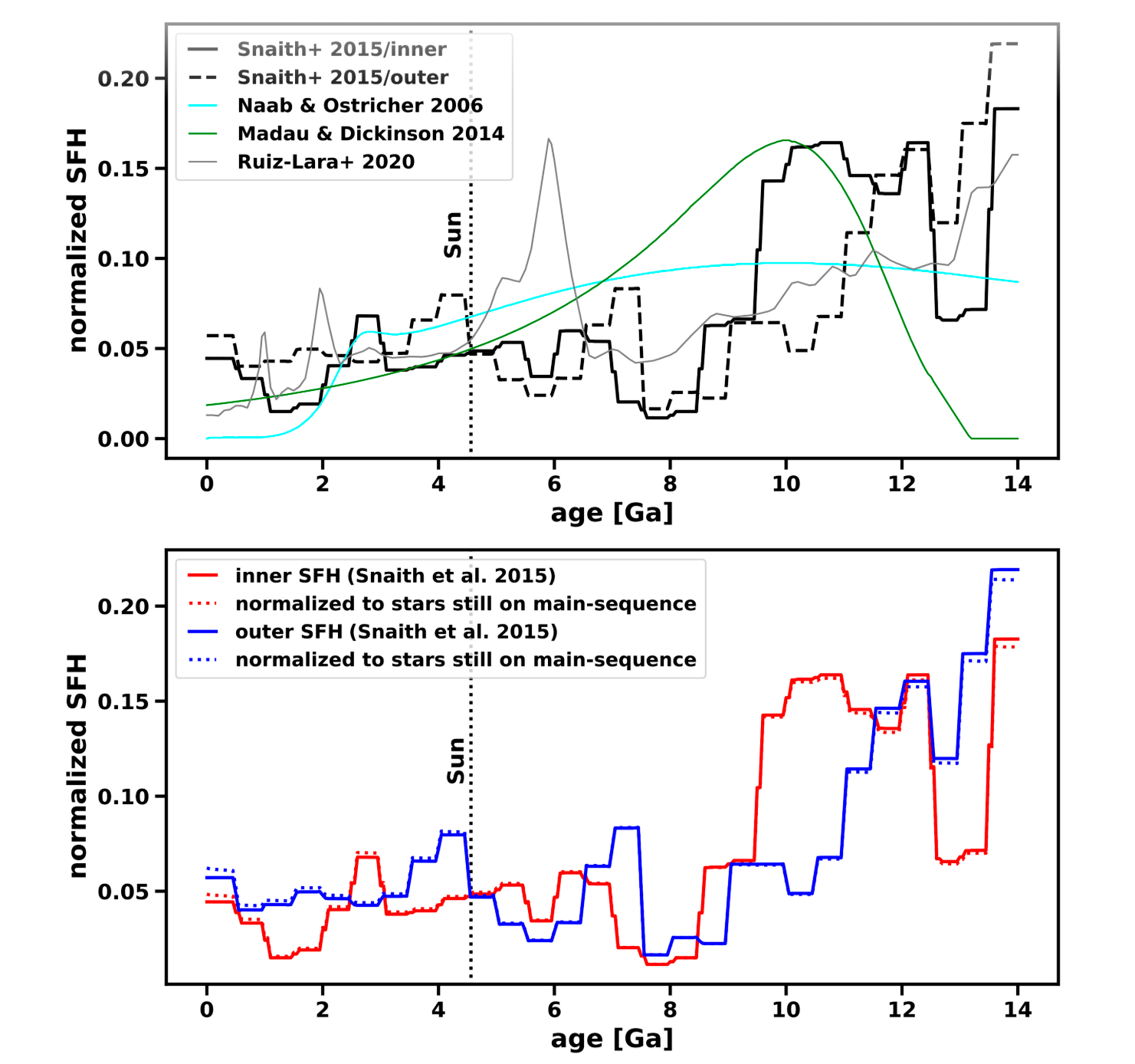

Dr. Lammer emphasized that Earth’s balance did not appear by chance. Instead, it emerged from billions of years of co-evolution between life and the atmosphere. Early microbes released oxygen. Geological processes recycled carbon and nitrogen. Together, these processes stabilized the climate long enough for complex life to evolve. This history defines a very small target. Few planets are likely to follow the same path.

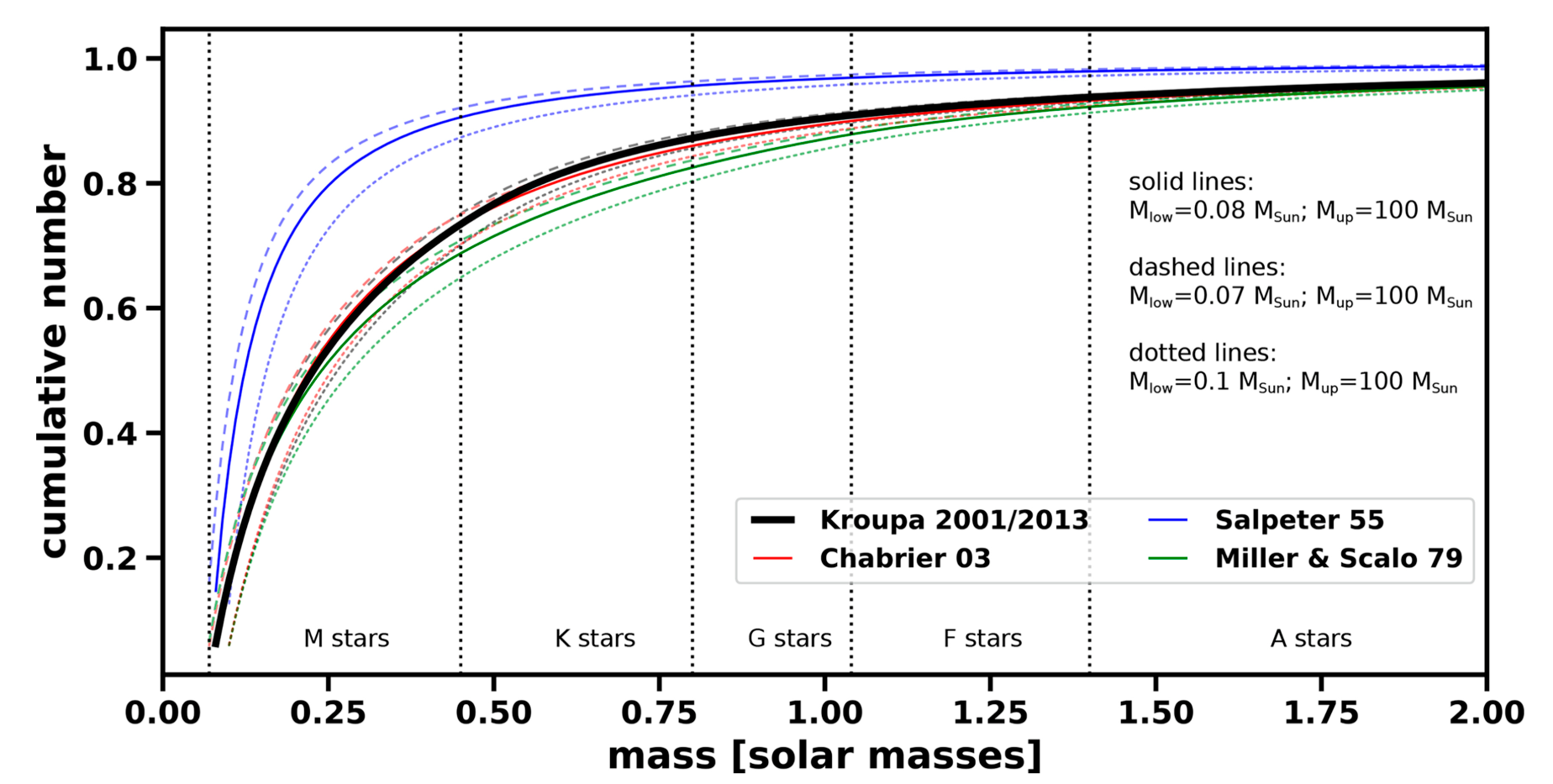

Many recent exoplanet discoveries orbit M-dwarf stars, also known as red dwarfs. These stars are common and easier to study, which explains why they dominate planet catalogs. Yet the researchers argued that they pose serious obstacles for Earth-like life.

Red dwarfs emit intense ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, especially during their early lives. This radiation heats planetary upper atmospheres and drives gases into space. Even thick carbon dioxide atmospheres struggle to survive. Nitrogen-oxygen atmospheres like Earth’s erode even faster.

Observations with the James Webb Space Telescope reinforce this concern. Several planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system show no clear signs of an atmosphere. Even if a thin atmosphere remains on some worlds, other challenges persist.

“Frequent stellar flares can damage biological molecules and strip gases away. Many red dwarf planets are tidally locked, with one side always facing the star. The day side risks overheating, while the night side can become cold enough for atmospheric gases to freeze and collapse. Without circulation, climates become unstable, Dr. Steel told The Brighter Side of News.

Large moons may also be rare around these planets. On Earth, the Moon helps stabilize rotation and climate patterns. Without that stabilizing influence, a planet’s tilt and seasons may vary widely, adding stress to any developing biosphere.

Because of these combined factors, Dr. Scherf and Dr. Lammer argued that Sun-like, G-type stars remain better candidates for Earth-like evolution, even though they are less common.

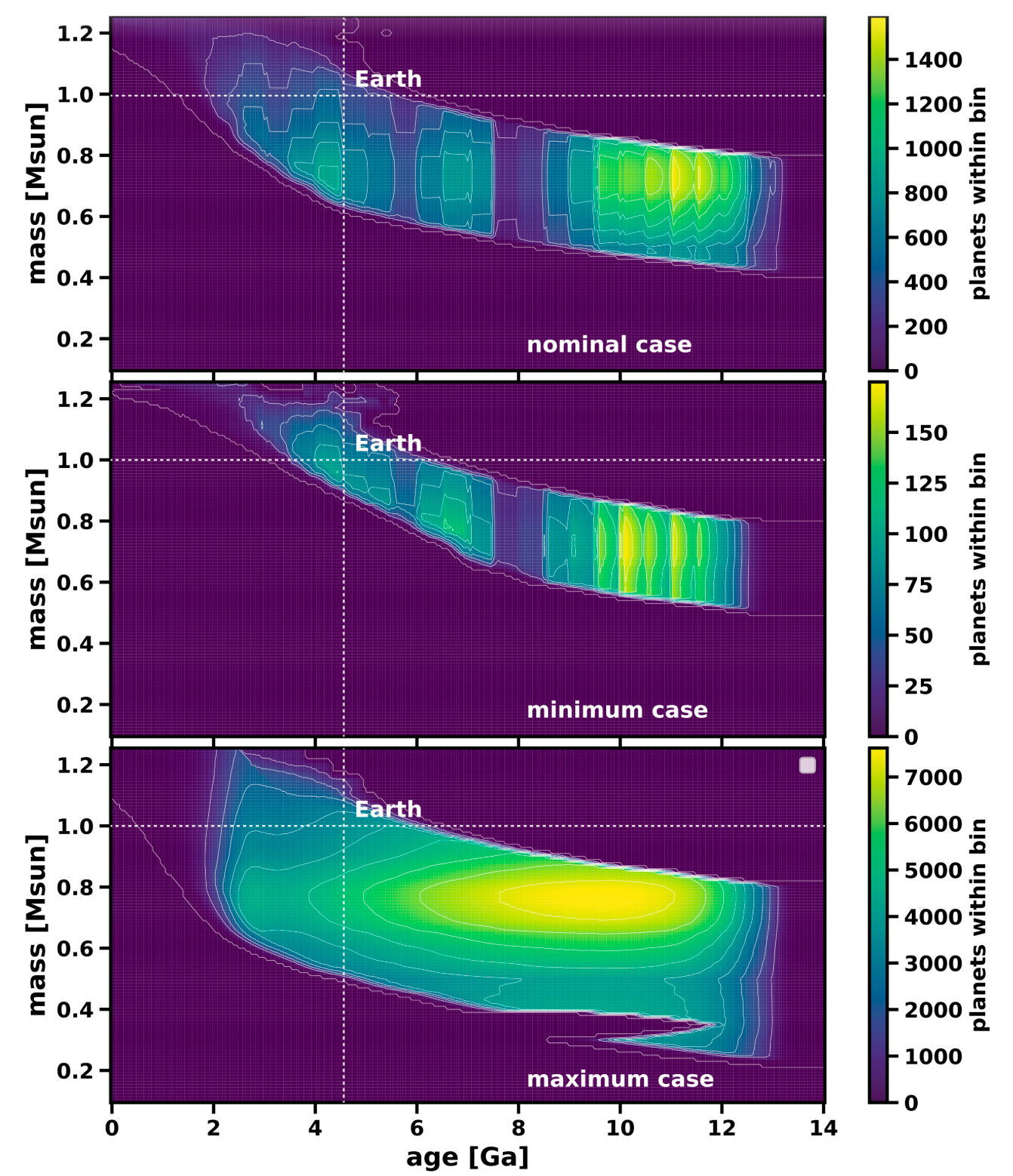

To estimate how many planets might meet these strict criteria, the researchers developed a modified version of the Drake Equation. This approach focused only on factors that can be measured or estimated today. These include how often rocky planets form in habitable zones, how well atmospheres are retained, and where planets sit within the galaxy’s habitable region.

Even with optimistic assumptions, the result was modest. The Milky Way may host between 60,000 and 250,000 planets with atmospheres similar to Earth’s. That figure spans a galaxy with hundreds of billions of stars.

This estimate does not include the steps required for life to begin. Abiogenesis, the origin of life from nonliving chemistry, remains poorly understood. From there, life must become complex, develop intelligence, and eventually produce technology.

Each step acts as a filter. If any stage is unlikely, the final number of technological civilizations shrinks sharply. When all filters are considered, only a handful of civilizations may exist at the same time in the galaxy. They could be separated by immense distances or arise millions of years apart.

This perspective offers one explanation for the lack of detected signals from extraterrestrial intelligence. If intelligent life is rare and brief on cosmic timescales, communication windows may rarely overlap.

Despite the sobering outlook, the researchers also outlined paths forward. New telescopes and missions could test whether Earth-like worlds are truly rare or simply hard to find.

One goal is to identify rocky planets that still retain their original hydrogen-helium atmospheres. These worlds reveal how quickly planets lose gases and how radiation shapes atmospheric evolution.

Another target involves planets with carbon dioxide-dominated atmospheres. Studying these planets may clarify why some worlds stall in early atmospheric states while others develop long-term stability.

Researchers are also focusing on rocky planets orbiting quieter K-type and G-type stars. These stars emit less damaging radiation and may allow atmospheres to persist for billions of years. Comparing planets across stellar types will refine models of habitability.

The most ambitious objective is direct imaging of Earth-sized planets around Sun-like stars. NASA’s proposed Habitable Worlds Observatory and Europe’s LIFE mission aim to detect atmospheric gases such as water vapor, oxygen, and nitrogen. Such observations would offer the clearest test yet of how common Earth-like conditions really are.

The discussion led by Dr. Steel, Dr. Scherf, and Dr. Lammer reflects a shift in astrobiology. Simple measures such as orbital distance no longer define habitability. Instead, chemistry, radiation, geology, and time all matter.

This broader view suggests that microbial life may be widespread, but the leap to intelligence is rare. Earth’s history shows how easily that path could have failed. Small changes in oxygen levels, carbon cycling, or solar behavior might have prevented complex life from emerging.

As observations improve, scientists will continue refining their estimates. Each new discovery helps clarify whether Earth is typical or exceptional. For now, evidence points toward a universe rich in planets but sparse in worlds that truly resemble home.

Research findings are available online in the journal Astrobiology.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Intelligent life may be far more rare than scientists previously thought appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.