You have likely heard Europa described as one of the most promising places to search for life beyond Earth. The icy moon of Jupiter holds a global ocean beneath its frozen surface, along with the basic chemical ingredients linked to biology. Now, a new analysis using data from NASA’s Juno spacecraft offers the clearest limits yet on how thick that ice shell may be, a detail that shapes how scientists think about Europa’s habitability.

The research, published in Nature Astronomy, was led by S. M. Levin and colleagues from JPL, Caltech, Stanford, Purdue and other prestigious universities. Findings draw on observations collected during Juno’s close flybys of Europa. Although Juno was designed to study Jupiter’s atmosphere and interior, the team found a way to repurpose one of its instruments to probe Europa’s ice. Their work suggests the moon’s ice shell is far thicker than some earlier estimates, likely measuring between 19 and 39 kilometers.

This finding narrows a long-running debate and adds new context to the question of whether Europa’s buried ocean could support life.

Europa has drawn scientific attention for decades because it combines extreme cold with an abundance of organic elements such as carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. Beneath its fractured ice crust lies a salty ocean that may contain more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. That combination has fueled speculation that Europa could host life.

Yet one key variable has remained uncertain. Scientists have struggled to determine how deep the ocean lies beneath the ice. No spacecraft has directly drilled or radar-mapped the entire shell. Instead, researchers have relied on indirect clues, including the shapes of impact craters and how the surface flexes under stress.

Those approaches produced estimates that varied widely. Some studies suggested the ice might be just one or two kilometers thick. Others argued for shells tens of kilometers deep. This uncertainty made it hard to assess how materials move between the surface and the ocean below.

Juno has orbited Jupiter for nearly two years and has completed several close passes of Europa. During those flybys, its instruments captured new information about the moon’s surface and interior.

“Our research team focused on Juno’s Microwave Radiometer, or MWR. The instrument was built to measure microwave emissions from deep within Jupiter’s atmosphere. However, the same physical principles apply to icy surfaces,” Levin told The Brighter Side of News.

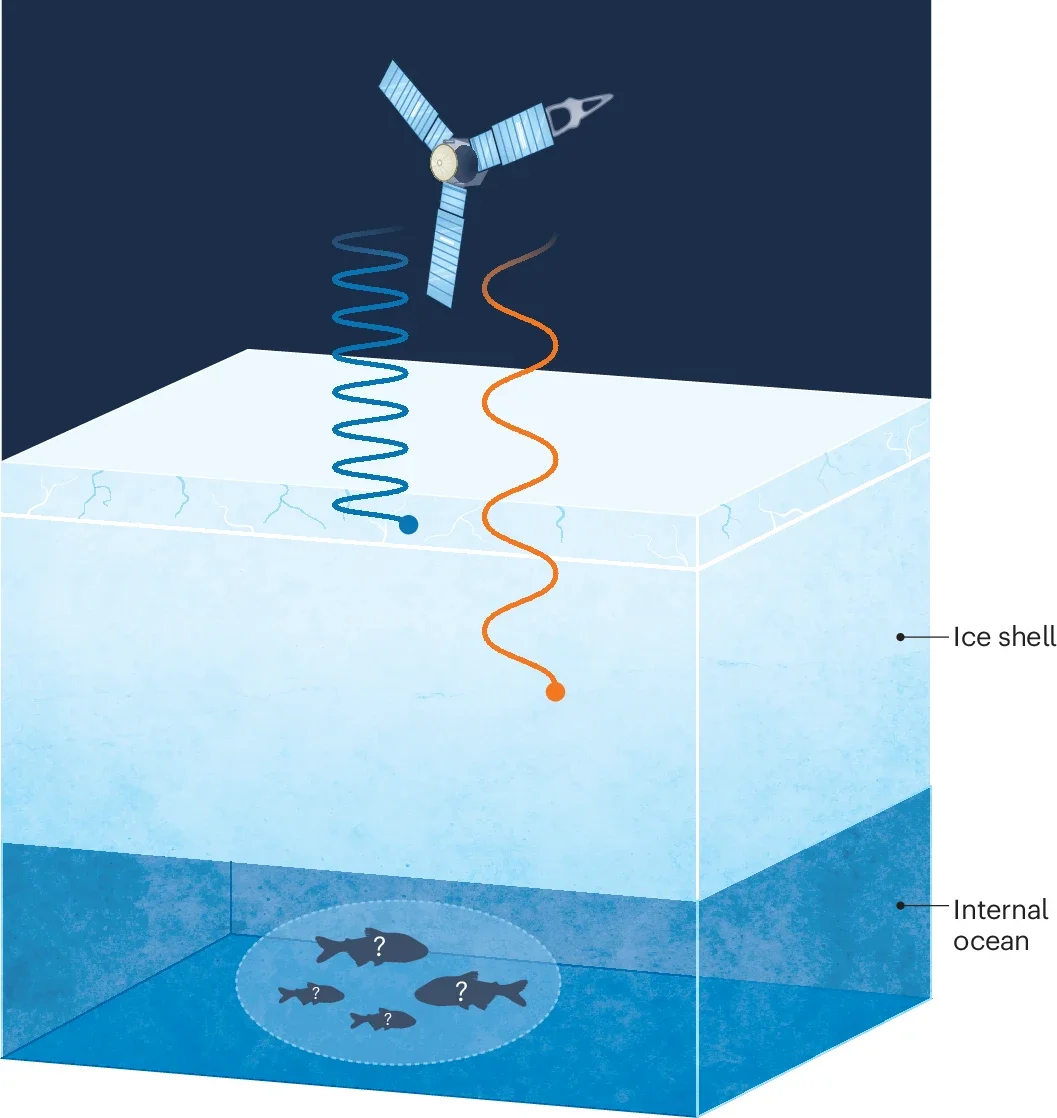

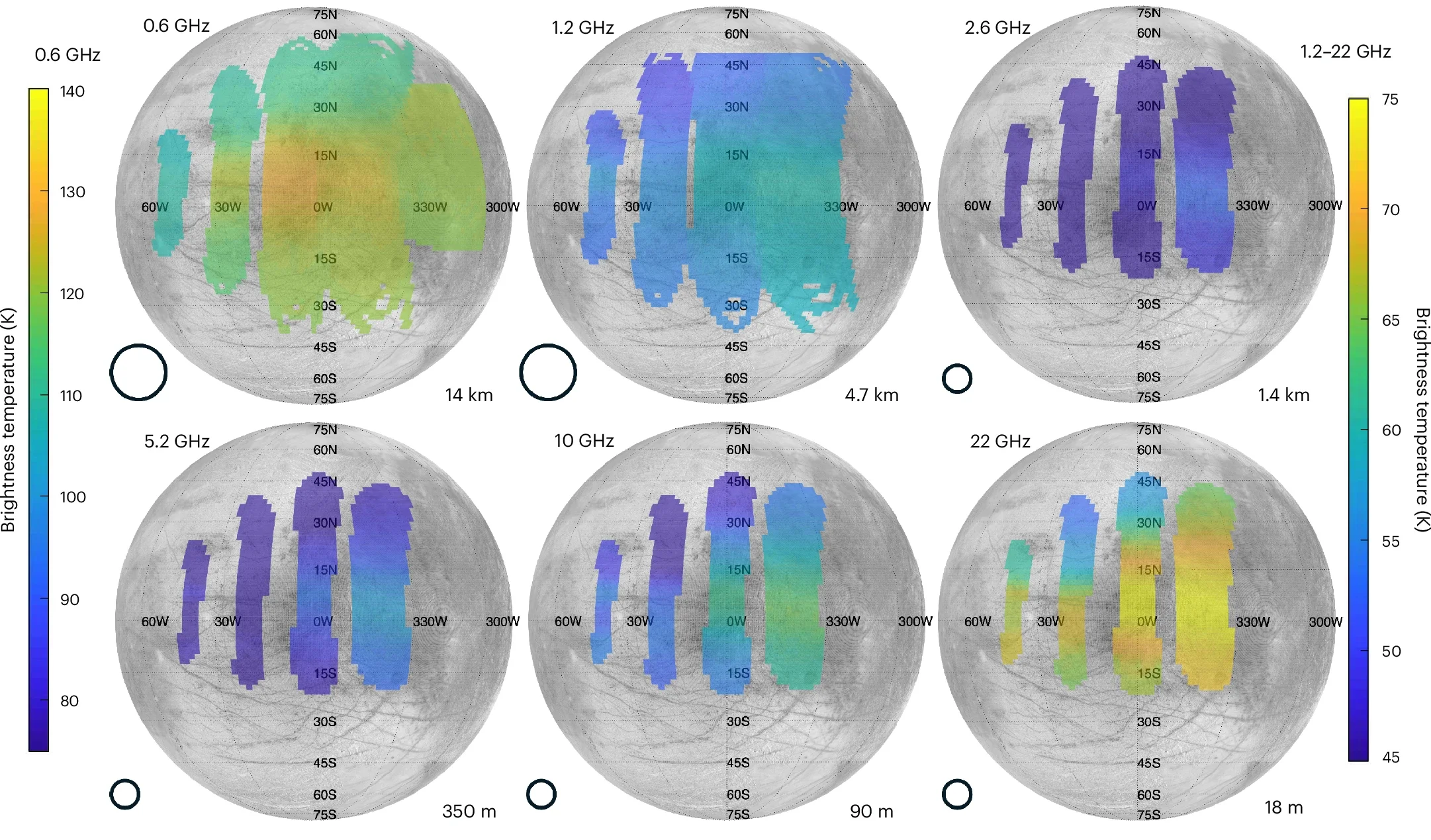

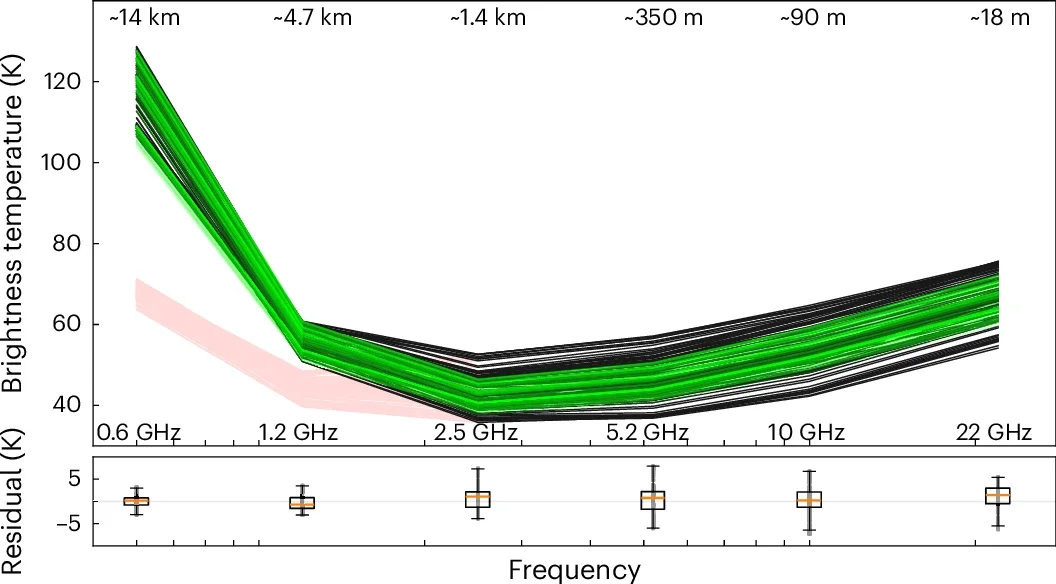

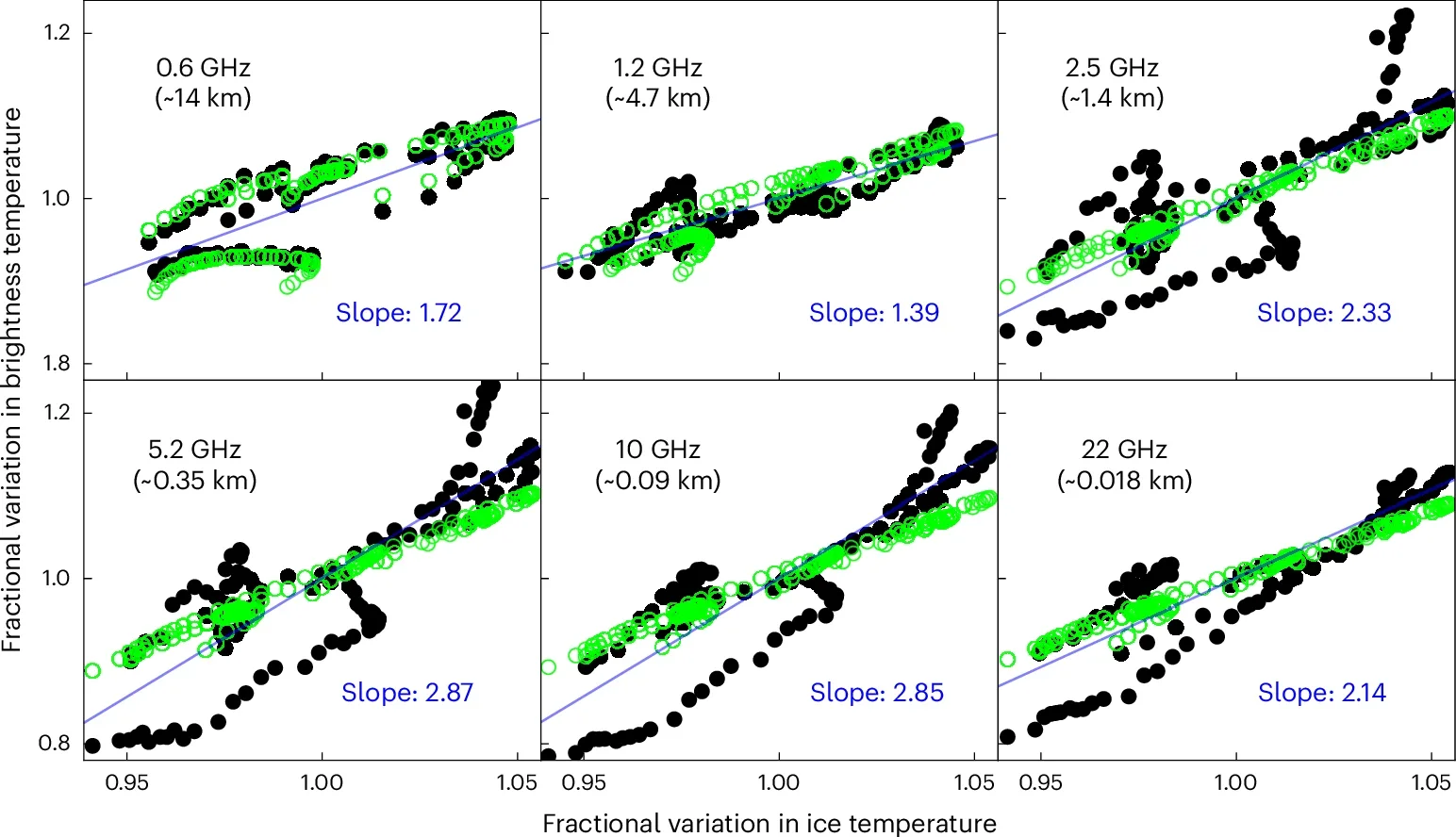

Europa’s ice emits microwave radiation that varies with temperature. Different microwave frequencies can also penetrate to different depths. Juno’s MWR measures six frequencies, allowing scientists to infer temperatures from just below the surface down to several kilometers deep.

“By analyzing these signals, our team reconstructed temperature profiles across parts of Europa’s ice shell. These profiles reveal how heat moves through the ice, both vertically and sideways,” Levin continued.

When the researchers compared temperature changes with depth, they identified where ice would likely transition to liquid water. That boundary marks the top of the subsurface ocean.

Their analysis points to an ice shell roughly 19 to 39 kilometers thick. While the estimate remains uncertain, it rules out the idea of a shallow ocean lying just beneath the surface.

The data also revealed fractures within the upper kilometer of ice. These cracks appear to play an important role in linking surface processes to the deeper ice. Still, the study concludes that Europa’s ocean is far more isolated than some earlier models suggested.

At first glance, thicker ice might seem bad for habitability. A deep shell could limit how surface materials reach the ocean. But the relationship is more complex.

Life on Earth relies on chemical reactions that move electrons between molecules. These reactions often depend on oxidants and reductants being brought together. On Europa, intense radiation from Jupiter breaks apart surface ice, creating oxidizing chemicals. The surface itself is too hostile for life, but those oxidants could serve as energy sources if they reach the ocean.

A thick ice shell may slow this transport, but it may not stop it. Thick ice can undergo convection, with warmer ice rising and cooler ice sinking. This slow churning could help move oxidants downward over time.

In this sense, a thicker shell might support a steady, long-term energy supply, even if transport is limited.

Detecting life on Europa remains difficult. Any signs of biology in the ocean would need to travel upward through kilometers of ice before reaching the surface, where spacecraft could detect them.

Heat conduction in the upper ice may block this movement. However, surface features suggest that liquid water has reached the surface in the past. These episodes may have occurred through localized melting or ocean upwelling.

Such events raise the possibility that biosignatures could sometimes be delivered closer to the surface. Still, scientists do not yet understand how often this happens or under what conditions.

Future answers will likely come from NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, set to arrive in the Jupiter system in 2030. Europa Clipper carries a suite of instruments designed to study the moon’s ice shell and ocean, including a ground-penetrating radar.

Unlike Juno, Europa Clipper does not include a microwave radiometer. Even so, the creative use of Juno’s data provides a valuable foundation. As Europa Clipper maps the ice in detail, scientists will be able to reinterpret the microwave results with greater confidence.

Together, these missions will help clarify how Europa’s ice works and how it affects the moon’s potential for life.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post NASA’s Juno spacecraft offers fresh insight into Europa’s icy ocean and its potential to support life appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.