Museums have spent decades trying to make the distant past feel alive. Audiovisual shows, touch screens and digital displays have helped, but they are often expensive to develop and hard to update when new discoveries come in. That cost has kept many smaller museums and research groups on the sidelines, watching as big commercial studios shape how most people picture ancient history.

Blockbuster game series such as Assassin’s Creed or Civilization have brought prehistoric and ancient worlds to millions of players. They are visually stunning, but they do not always treat accuracy as a top priority. For archaeologists who spend their lives working with fragile evidence, it can be frustrating to see the past turned into a backdrop rather than a carefully told story.

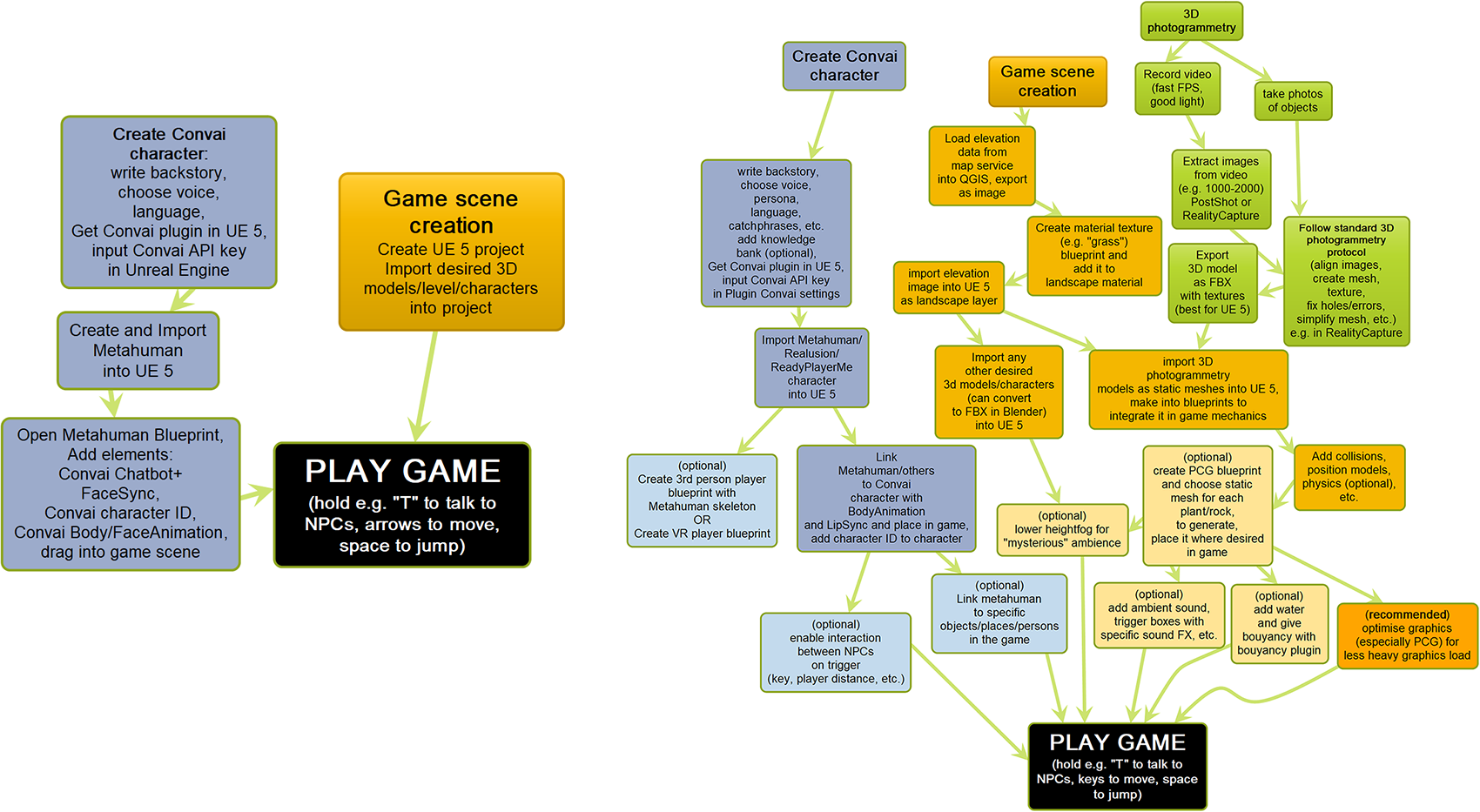

A team at the University of Copenhagen decided to see whether that could change. In a new research paper, they show that with artificial intelligence, the free game engine Unreal and open tutorials on YouTube, it is now possible for beginners to build their own educational 3D game about the Stone Age in a short time and for very little money.

“We believe that these free tools that are now available to everyone have the potential to revolutionize digital cultural heritage communication. And with the research article about our game, we give other professionals the recipe for how to get started with digital storytelling without spending huge resources on it,” said archaeologist Mikkel Nørtoft from the University of Copenhagen.

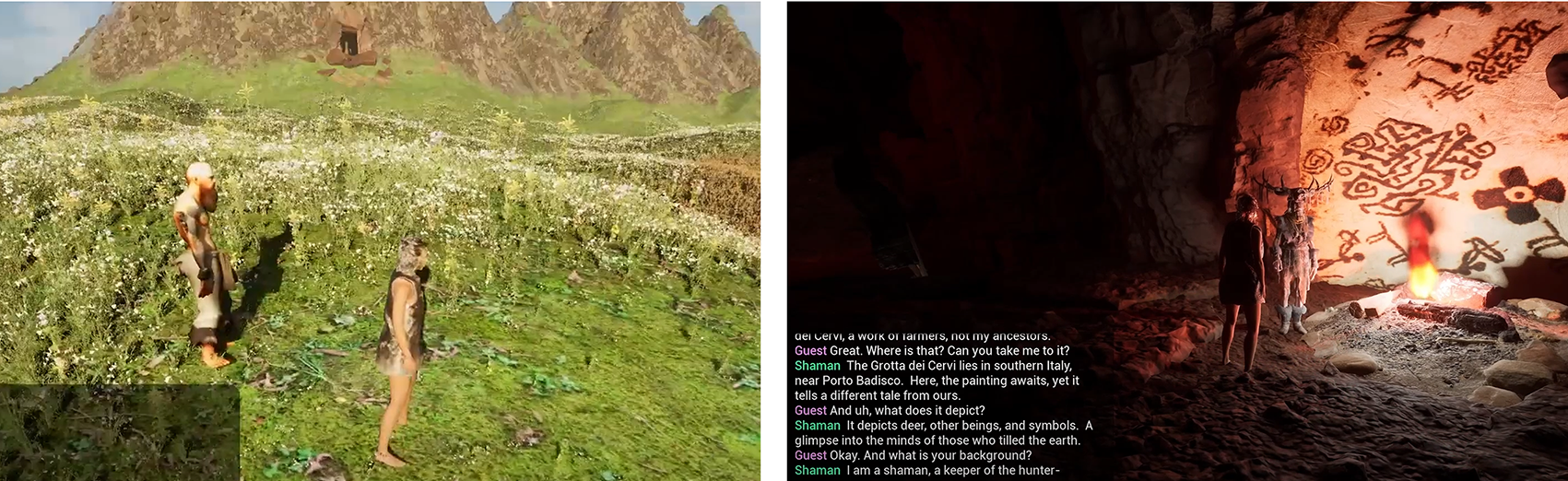

The game that Nørtoft and his colleagues created grows out of the Deep Histories of Migration research project, which studies the Neolithic period in northern Europe. Instead of inventing a fantasy setting, the team went to a real site on the Danish island of Funen, Lindeskov Hestehave, and recorded two remarkably well preserved long dolmens.

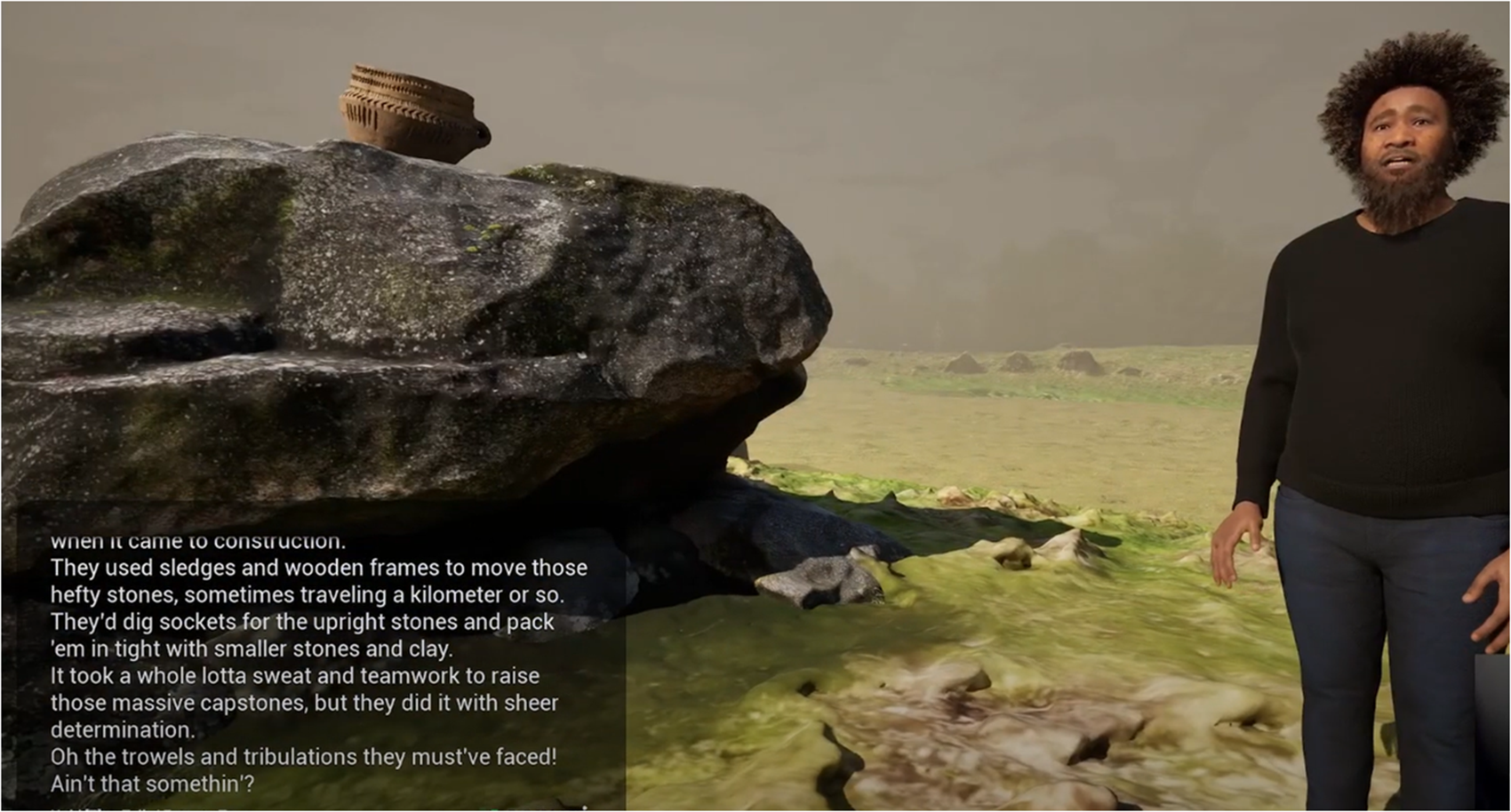

Back at their computers, they used those recordings to build a detailed 3D landscape in Unreal Engine. That digital site became the stage for a small but rich game world where the goal is simple and human: you explore, you ask questions and you come to understand how people in the Stone Age buried their dead and made sense of their world.

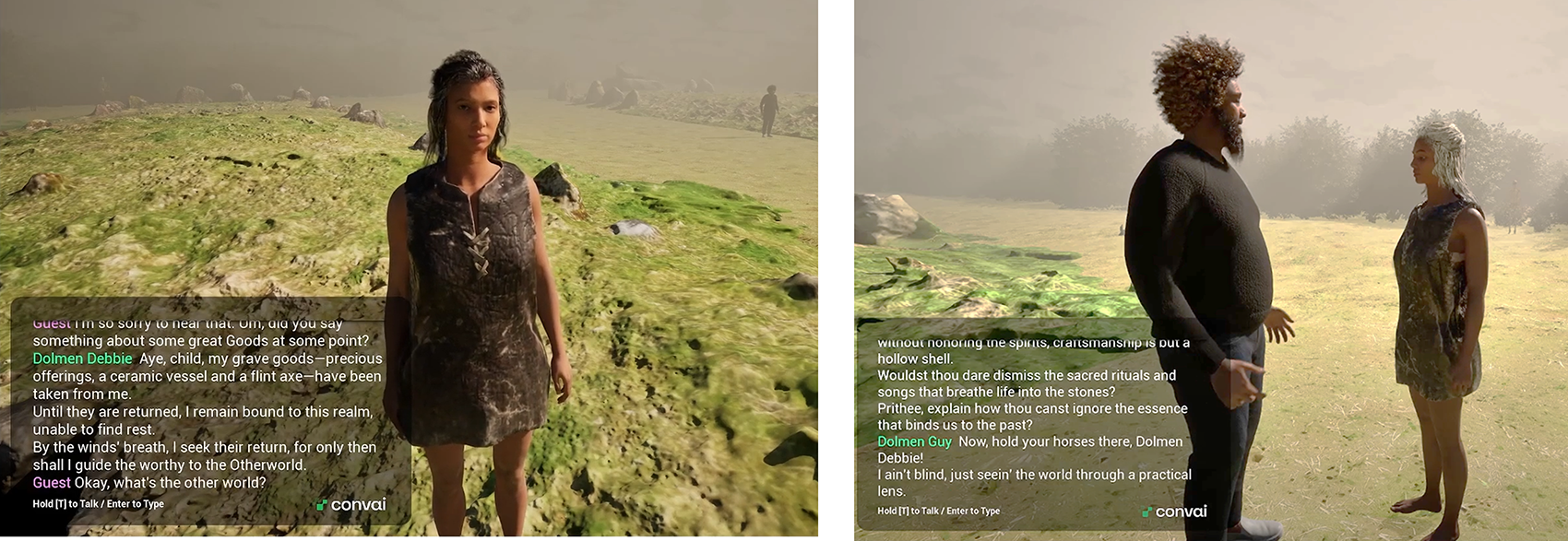

The experience is not meant to feel like a textbook. It is closer to walking through the forest with company. As you move around the dolmens, you meet two characters, an archaeologist and a Stone Age woman, who guide you through the site and its stories.

Those characters are not trapped in rigid scripts. They are driven by generative AI and speak using large language models fed with background stories and curated archaeological knowledge banks.

“In other words, we haven’t had to write detailed manuscripts because the characters speak using generative AI and can therefore express themselves – optionally in several different languages – based on our prompts and our own compiled archaeological knowledge banks,” Nørtoft explained.

In practice, that means you can walk up to the digital archaeologist and ask about the building techniques behind the long dolmens or the dating of the stones. Then you can turn to the Stone Age woman and ask what the burial place means to her family or how her community treats the dead. Their answers draw on the same research, but they come through different voices.

“Because the game leans on AI, the conversation feels more like a dialogue than a lecture. The characters can respond in flexible ways and keep the discussion going, rather than repeating the same lines every time you click on them. For international visitors, they can also switch languages, which opens the site to many more players than a traditional exhibition label,” Nørtoft explained to The Brighter Side of News.

One of the biggest practical changes comes from how easy it is to update the content. In earlier digital projects, changing a storyline often meant hiring programmers and rewriting large blocks of code. That made many museums wary of complex digital storytelling.

Here, the core facts live in prompt texts and knowledge banks that the researchers themselves control. When new findings come in, they can adjust the backstories and source files without rewriting the entire game. The characters then draw on those updated materials the next time someone plays.

This feedback loop matters if you care about accuracy. Archaeological knowledge shifts as new digs are completed and old finds are reanalyzed. The team’s setup lets the communication stay on solid academic ground while still feeling immediate and natural to players. The story of the dolmens can grow as the science grows.

The researchers stress that their game is mainly a proof of concept, a modest first attempt meant to show what is technically possible for beginners. They are not claiming to have built the ultimate Stone Age game. Instead, they want to hand the tools to others.

“Our game is primarily an example of what is technically possible for beginners, so we recommend that museums and other interested parties build their own scenarios with their expert knowledge. With a little help, most people will be able to learn how to build a simple scenario with characters within a few days and start experimenting with this type of dissemination,” Nørtoft said.

For archaeologists and historians, that is a major shift. Instead of depending on expensive commercial developers, they can now take control of how their subject is shared in digital spaces. A small local museum could build a game around its own burial mound, farmstead or shipwreck. A classroom could adapt the idea for a student project and let teenagers talk with a virtual Iron Age farmer.

The point is not to replace physical sites or original artifacts. It is to add a layer of interaction that helps you feel a connection with people who lived thousands of years ago, without losing the careful work that goes into serious research.

These findings hint at a quiet revolution in how the past can be presented. With AI driven characters, free engines like Unreal and basic online training, cultural institutions no longer need blockbuster budgets to create engaging digital experiences.

For museums, the approach offers a way to build interactive exhibits that can be updated as scholarship changes, instead of freezing a story in place for a decade. In schools, it offers ready made models for project based learning, where students can explore a site, ask questions and test what they learned in class against what the AI characters say.

As for archaeologists and historians, the method restores control. They can ensure that the digital versions of their sites remain research based, while still making room for drama, emotion and multiple perspectives. Communities connected to specific sites could also participate, shaping the prompts and backstories so that local voices become part of the experience.

Looking ahead, as language models improve and game tools become even easier to use, this recipe could extend far beyond the Neolithic forest on Funen. The same approach could bring Bronze Age trade routes, medieval towns or colonial harbors into playable form. In each case, the goal would be the same: to let you step into the landscape of the past, talk with its people and come away with a deeper, more personal understanding of history.

Research findings are available online in the journal Advances in Archaeological Practice.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post AI helps archaeologists build low-cost stone age video games in days appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.