More than a billion years ago, a shallow basin in what is now northern Ontario held a subtropical lake. The setting likely resembled modern Death Valley, where heat drives evaporation and leaves salt behind. As that ancient lake dried, crystals of halite formed. Tiny pockets of brine and air became trapped inside the salt. Those pockets sealed a direct sample of Earth’s atmosphere and preserved it for about 1.4 billion years.

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute have now opened that archive. The team was led by graduate student Justin Park and guided by geology professor Morgan Schaller. By analyzing gases trapped inside the halite, they extended direct measurements of Earth’s atmosphere far deeper into the past than ever before. Their work appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The period they studied sits within the Mesoproterozoic eon, a stretch of time from about 1.8 to 0.8 billion years ago. Life then was simple. Bacteria dominated ecosystems. Red algae had only begun to appear. Animals and land plants were still hundreds of millions of years away.

Yet the atmosphere captured in those crystals tells a more complex story.

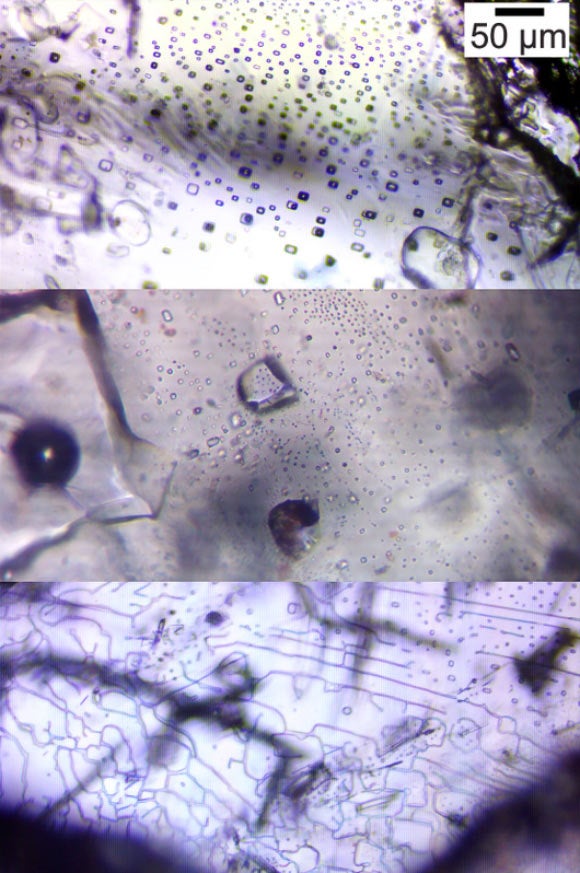

Opening ancient salt to read its chemical record is not straightforward. Fluid inclusions in halite contain both air bubbles and salty water. Gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide dissolve differently in water than they exist in air. That makes it difficult to reconstruct the original atmosphere.

Park developed new techniques to solve that problem. Working with custom-built lab equipment, he separated the gas signals and corrected for how each gas behaves in brine. The approach allowed the team to extract reliable measurements from primary inclusions that formed when the salt crystals first grew.

“It’s an incredible feeling, to crack open a sample of air that’s a billion years older than the dinosaurs,” Park said.

Schaller said the advance goes beyond technical novelty. “The carbon dioxide measurements Justin obtained have never been done before,” he said. “We’ve never been able to peer back into this era of Earth’s history with this degree of accuracy. These are actual samples of ancient air.”

The halite crystals were buried soon after they formed and remained isolated from later contamination. That isolation gives researchers confidence that the gases reflect conditions at the time, not later changes.

The measurements show that oxygen levels during this window of the Mesoproterozoic reached about 3.7 percent of modern atmospheric levels. That may sound low, but it is higher than many scientists expected. It is also high enough to support simple animals, at least from a metabolic standpoint.

Carbon dioxide levels were also striking. They were roughly ten times higher than preindustrial levels. That concentration would have helped warm the planet when the Sun was fainter than it is today. The result, the researchers say, was a climate not unlike the modern one.

“These findings help resolve a long-standing puzzle. Indirect estimates of carbon dioxide had suggested levels too low to prevent global glaciation. Yet the geological record shows no major ice ages during this era. These new direct measurements align with the absence of glaciers and point to a long stretch of relatively mild climate,” Schaller told The Brighter Side of News.

“They also raise a deeper question. If oxygen levels were sometimes high enough for animals, why did complex life take so long to appear?” he thought.

Park also cautioned against overgeneralizing from a single snapshot. “It may reflect a brief, transient oxygenation event in this long era that geologists jokingly call the ‘boring billion,’” he said. The nickname reflects the apparent stability of the period, with little change in climate or life.

Despite the name, Park said direct evidence from this time is rare and valuable. “Having direct observational data from this period is incredibly important because it helps us better understand how complex life arose on the planet, and how our atmosphere came to be what it is today,” he said.

The team also measured the temperatures at which the fluid inclusions formed. Those temperatures averaged just over 31 degrees Celsius, with some variation. Combined with high carbon dioxide levels, the data suggest a warm but stable world.

Schaller noted that red algae emerged around this time and still play a major role in producing oxygen today. The rise of more complex algae may have pushed oxygen levels higher, at least temporarily. Plate tectonics may have contributed as well. The breakup of the ancient supercontinent Nuna could have altered nutrient flows and chemical cycles in the oceans.

“It’s possible that what we captured is actually a very exciting moment smack in the middle of the boring billion,” Schaller said.

The findings support the idea that life, climate, and the atmosphere evolved together. Oxygen may have crossed critical thresholds earlier than once thought, even if animals did not immediately take advantage of those conditions.

The study reshapes how scientists think about Earth’s middle age. By providing direct measurements instead of indirect estimates, it gives researchers firmer ground for testing models of climate and biological evolution. It shows that stable, warm climates can persist alongside relatively low but meaningful oxygen levels.

For future research, the methods open the door to studying other ancient salt deposits. Similar crystals could reveal how atmospheric changes unfolded across deep time. That knowledge can improve models of how planets regulate climate and sustain life.

For humanity, the work offers context. It shows that Earth maintained habitable conditions long before complex life emerged. Understanding those balances may guide the search for life on other worlds and clarify how resilient, and fragile, planetary systems can be.

Research findings are available online in the journal PNAS.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ancient salt reveals a clear view of Earth’s atmosphere from 1.4 billion-years-ago appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.