Astronomers at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian have captured what may be the biggest planet-forming disk ever seen around a young star; and it looks unexpectedly wild. Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the team led by Kristina Monsch reported a disk that is not just huge, but also messy, uneven, and threaded with faint wisps that rise far above its midplane. The study, published in The Astrophysical Journal, focuses on a system called IRAS 23077+6707, or IRAS23077 for short.

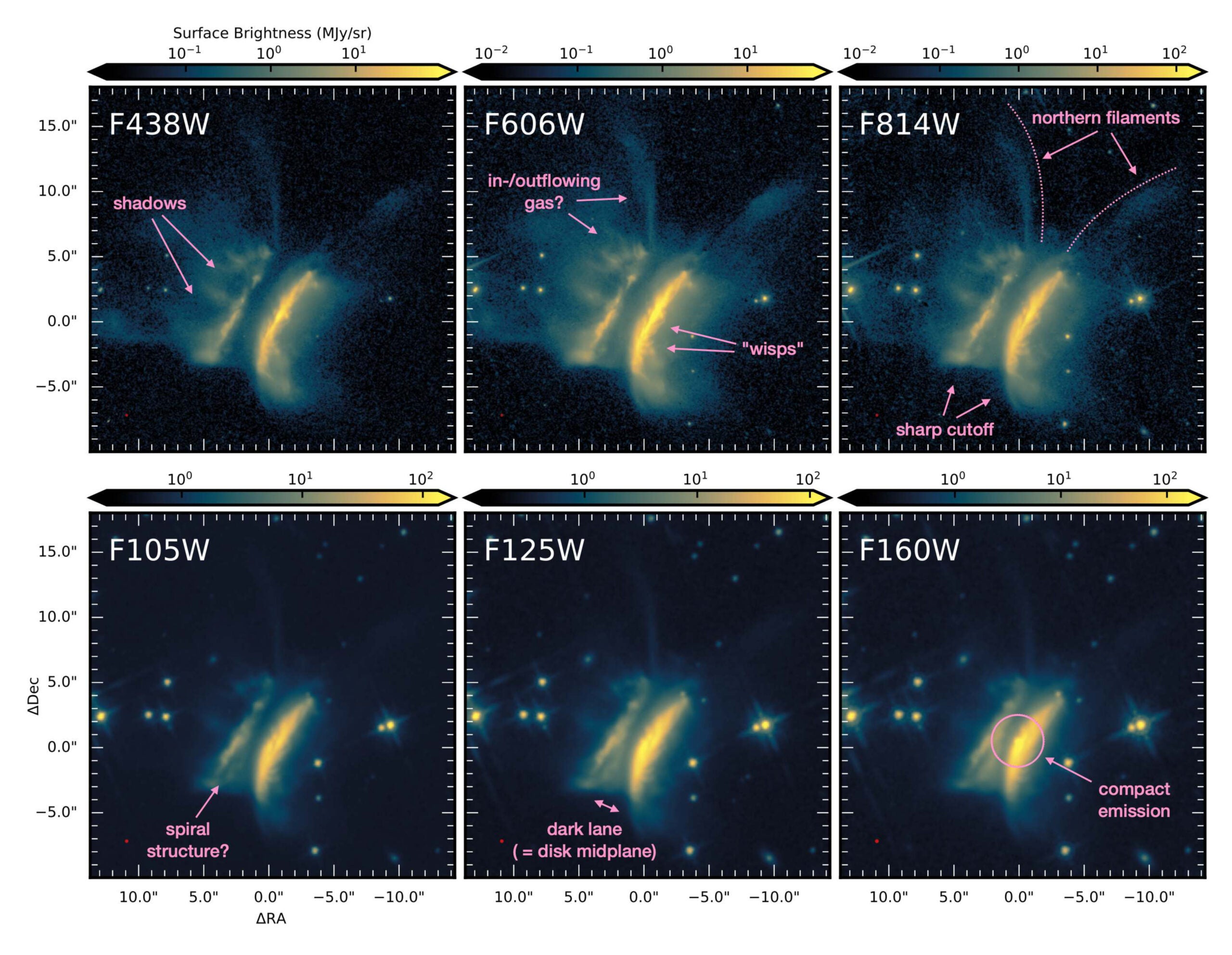

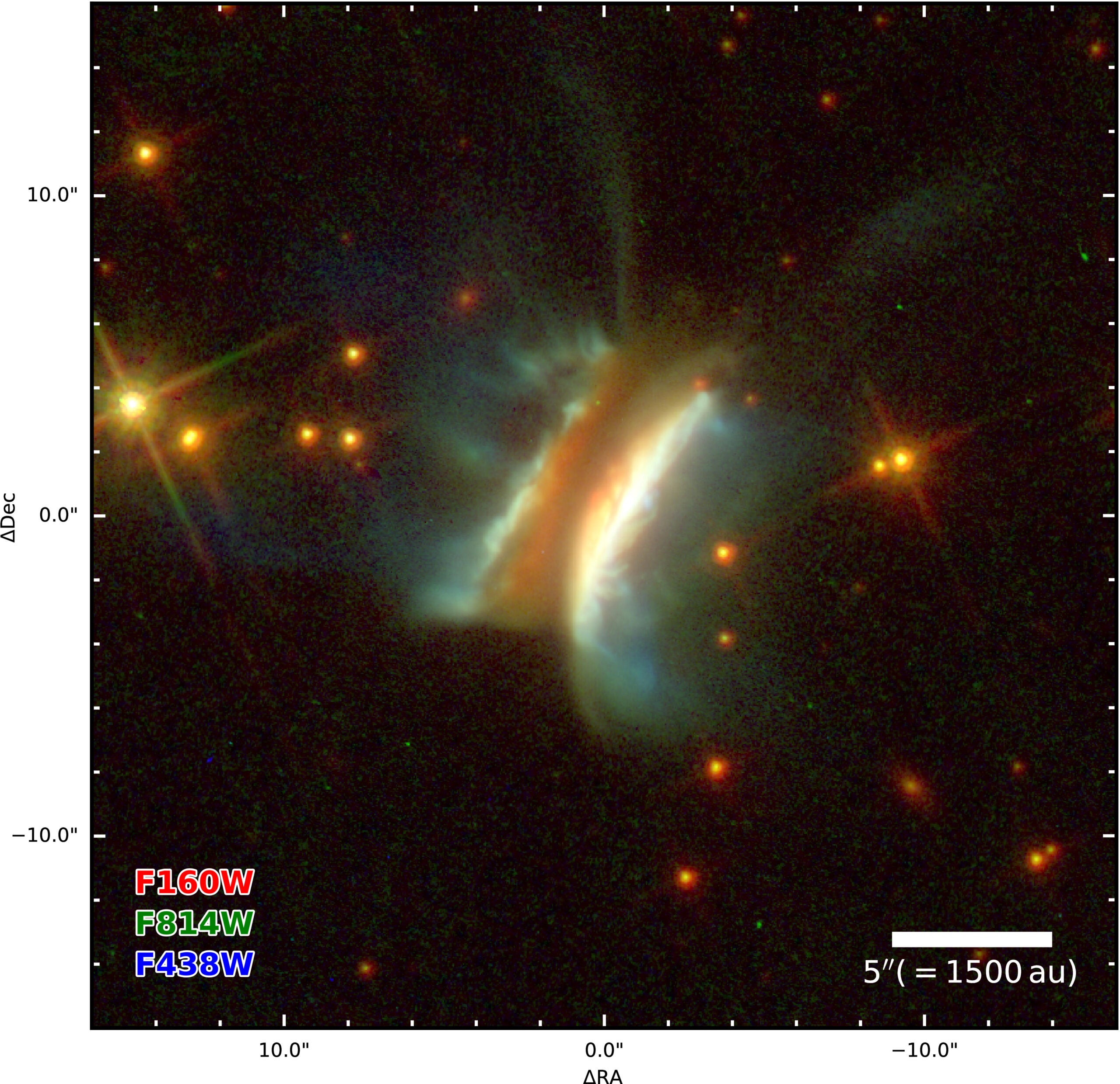

Hubble’s images show the disk nearly edge-on, a viewing angle that lets you see the structure in silhouette. That matters because the disk’s dust and gas block the star’s glare like a natural shade. Instead of a bright star washing everything out, you get a dark lane where dense material sits, plus two glowing “lobes” of scattered light above and below.

Located roughly 1,000 light-years from Earth, IRAS 23077+6707 spans nearly 400 billion miles. That is about 40 times the diameter of our solar system out to the Kuiper Belt. The disk hides the young star inside it. Scientists think the central object may be a hot, massive star, or a pair of stars.

“The level of detail we’re seeing is rare in protoplanetary disk imaging, and these new Hubble images show that planet nurseries can be much more active and chaotic than we expected,” said Monsch of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA). “We’re seeing this disk nearly edge-on and its wispy upper layers and asymmetric features are especially striking. Both Hubble and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have glimpsed similar structures in other disks, but IRAS 23077+6707 provides us with an exceptional perspective — allowing us to trace its substructures in visible light at an unprecedented level of detail. This makes the system a unique, new laboratory for studying planet formation and the environments where it happens.”

The team’s nickname for the disk, “Dracula’s Chivito,” nods to personal roots: one researcher from Transylvania and another from Uruguay, where a chivito is a national sandwich. The disk’s shape makes the joke easy. In visible light it resembles a hamburger, with a dark “patty” lane and bright “buns” above and below.

What stands out most is the disk’s unevenness. Hubble reveals tall, filament-like features on only one side. The other side looks cut off, with a sharper edge and no matching filaments. That kind of imbalance hints that something is actively shaping the disk, perhaps recent infall of gas and dust or an interaction with its surroundings.

“We were stunned to see how asymmetric this disk is,” said co-investigator Joshua Bennett Lovell, also an astronomer at the CfA. “Hubble has given us a front row seat to the chaotic processes that are shaping disks as they build new planets — processes that we don’t yet fully understand but can now study in a whole new way.”

The disk’s vertical reach is extreme. In the Hubble analysis, faint scattered light extends up to about 5 arcseconds above the midplane in the 0.8 micrometer images. If the system lies in the Cepheus star-forming region, as its position suggests, that height could translate to roughly 750 to 1,850 astronomical units. The distance is still uncertain because the object is too extended for accurate Gaia parallax.

Hubble also confirms prominent wispy structures across all six filters the program used. Some appear as bright features above the disk, while others look like darker foreground filaments. In an edge-on view, the outer disk can project in front of inner regions. That geometry suggests the wisps may trace outer material thrown into view, rather than a neat, settled layer.

Hubble observed IRAS23077 with the Wide Field Camera 3 using both UVIS and IR channels. The team collected images in six broadband filters from 0.4 to 1.6 micrometers during three Hubble orbits on Feb. 8, 2025. Exposure times ranged from 600 seconds to 2,100 seconds.

Across those wavelengths, the disk keeps its basic silhouette. But key details shift. The dark lane narrows as the wavelength gets longer. That change is not just a visual quirk. It connects to how dust blocks and scatters light, which can hint at grain size and how material is arranged above and below the midplane.

“Our research team quantified the disk’s lopsided brightness by measuring peak-to-peak ratios between the west and east lobes. The west side stayed much brighter, especially at shorter wavelengths. The ratios were 14.3 ± 0.9 at 0.4 micrometers, 10.1 ± 0.6 at 0.6 micrometers, 7.8 ± 0.4 at 0.8 micrometers, 6.5 ± 0.4 at 1.05 micrometers, 7.3 ± 0.5 at 1.25 micrometers, and 8.1 ± 0.5 at 1.6 micrometers,” Lovell told The Brighter Side of News.

Earlier work suggested the main west-to-east contrast could come from viewing geometry, since the disk tilt is about 80 degrees and the near side can look brighter in scattered light. Yet the disk’s patterns do not line up perfectly even after rotating images for consistent sampling. That mismatch reinforces the idea that the structure itself is genuinely uneven.

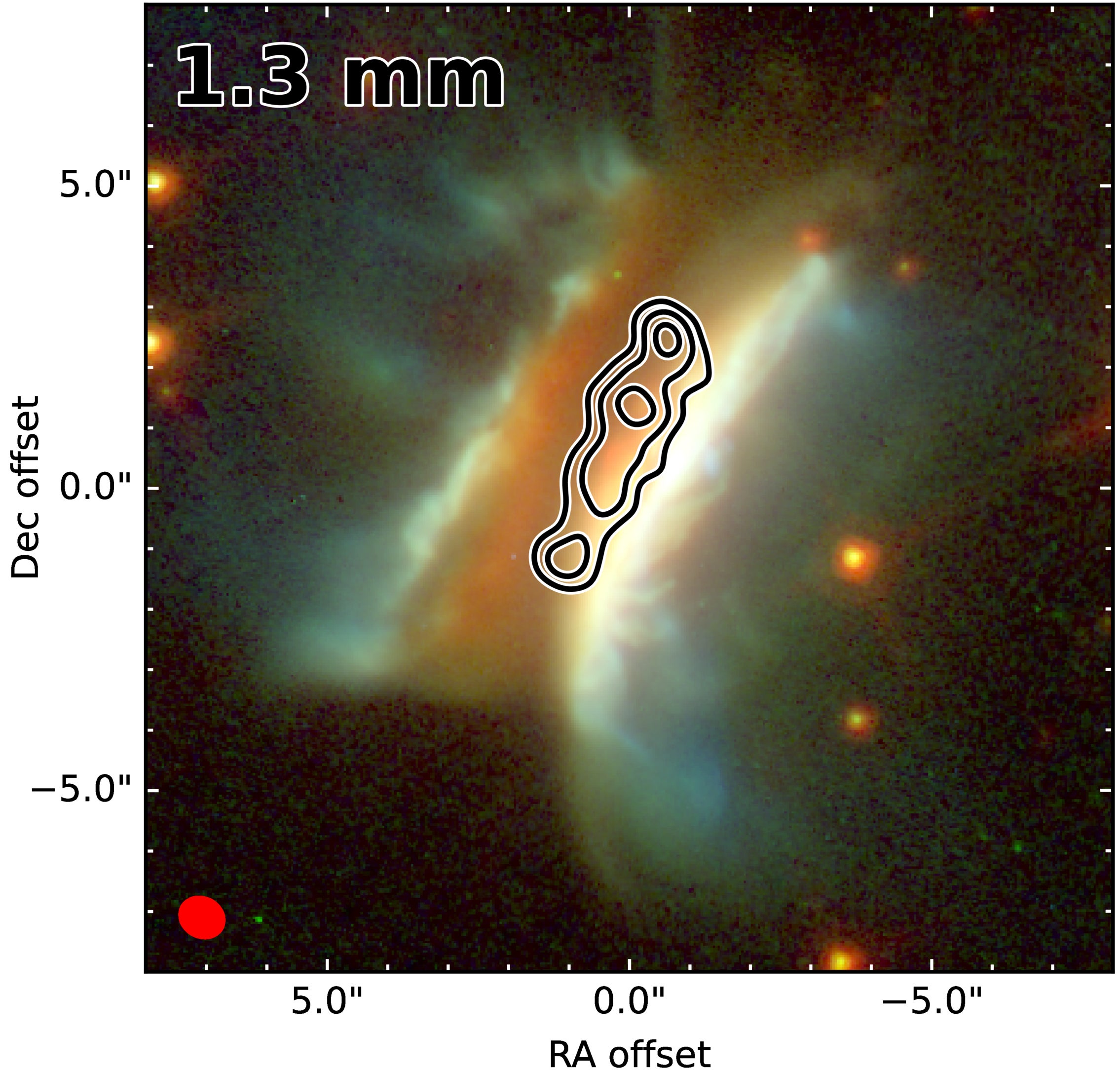

The dark lane’s thickness also shrank steadily with wavelength, from about 3.1 arcseconds at shorter optical wavelengths down to about 2.1 arcseconds at 1.6 micrometers. Millimeter measurements offer context too, with smaller thickness values at 1.3 to 3.1 millimeters.

This narrowing can be read two ways. One possibility is real dust settling, where larger grains sink toward the midplane over time. Another is an opacity effect, where longer wavelengths see deeper into the disk, making the lane appear thinner even if the dust is still mixed. The study notes that scattered light alone cannot prove settling, and current millimeter data do not have enough resolution to pick one story over the other.

All planetary systems start in disks of gas and dust. Over time, gas feeds the growing star, while the leftover material forms planets. IRAS23077 may be a scaled-up version of the early solar system, with a disk mass estimated at 10 to 30 times that of Jupiter. That is enough raw material to form multiple gas giants.

“In theory, IRAS 23077+6707 could host a vast planetary system,” said Monsch. “While planet formation may differ in such massive environments, the underlying processes are likely similar. Right now, we have more questions than answers, but these new images are a starting point for understanding how planets form over time and in different environments.”

The Hubble study also reports flux measurements across the six filters, showing brightness rising with wavelength. The team compared the new optical photometry with Pan-STARRS data from about a decade ago and found no significant optical variability within uncertainties. The study also describes NEOWISE mid-infrared monitoring over a decade, showing a mild brightening and weak color modulation.

One more detail appears in Hubble’s longest-wavelength filter. In the F160W images, the team spotted a compact emission feature near the center of the western lobe. It does not appear at shorter wavelengths and does not look like a true point source in processed images. The study interprets it as scattered or thermally emitted photons moving through the disk, not direct starlight.

Hubble also found no jet emission. Jets often appear in younger, strongly accreting systems. Their absence here supports the idea that the object is more evolved, fitting a Class II young stellar object.

Research findings are available online in The Astrophysical Journal.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Dracula’s Chivito: Hubble reveals the largest known planet-forming disk appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.