Randomness inside cells can decide whether a cancer returns after chemotherapy or whether an infection survives antibiotics. Even cells with the same DNA can act differently because their molecules rise and fall unpredictably. Those swings, often called biological noise, can create rare “outlier” cells that escape treatment.

A joint team led by Professor KIM Jae Kyoung of KAIST and the IBS Biomedical Mathematics Group, along with KIM Jinsu of POSTECH and Professor CHO Byung-Kwan of KAIST, reports a mathematical approach aimed at that problem. The researchers developed what they call a “Noise Controller” (NC), a framework meant to stabilize not only the average behavior of a cell population, but also the unpredictable variation from cell to cell.

The team’s central point is simple. Controlling the average can still leave dangerous exceptions. Those exceptions can drive drug resistance and relapse, even when most cells respond as expected.

Cells survive by keeping key internal conditions steady even when the outside world changes. Biologists call that stability homeostasis. Synthetic biologists try to copy that idea by building gene circuits that hold protein levels near a desired target.

Most classic strategies focus on the mean, or average, across many cells. That can look successful in a graph of population behavior. Yet individual cells can still swing widely around that mean.

The researchers describe the problem with a familiar example. “Standard control methods are like adjusting a shower,” they explained. “You might get the water to average 40°C, but if that average is achieved by alternating between freezing cold and boiling hot water, you can’t take a shower. Similarly, in biology, getting the average right isn’t enough if individual cells are fluctuating wildly.”

In medicine, those fluctuations matter. A small fraction of cells can land in a protected state. That minority can survive treatment and later repopulate.

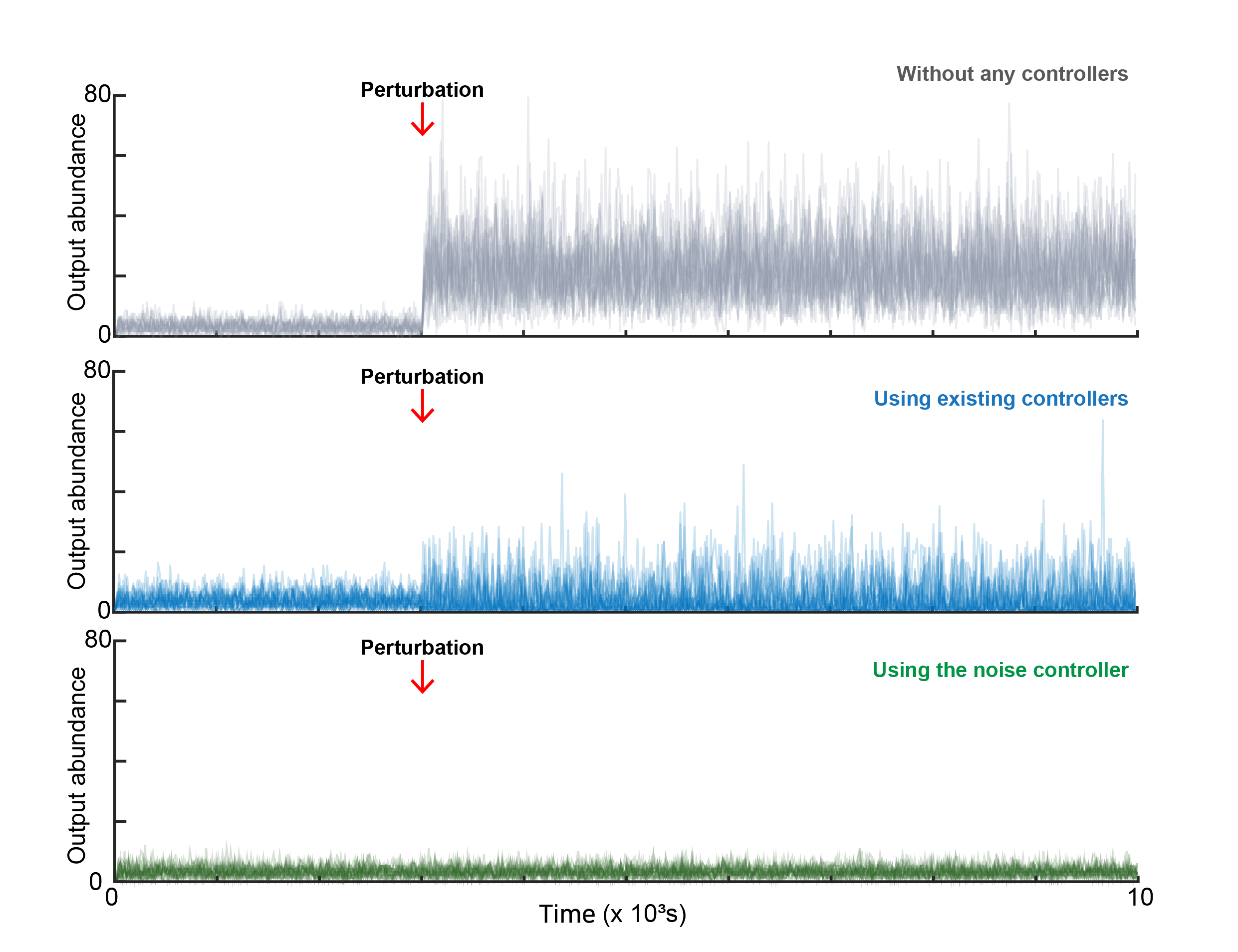

The team’s work builds on a widely used idea called robust perfect adaptation, or RPA. In plain terms, RPA means a system returns to a target level after a disturbance. One popular design can keep an output steady on average, even if conditions change.

But the catch is noise. A controller can hold the mean steady while the spread of outcomes widens. Some earlier work suggested this trade-off might be unavoidable.

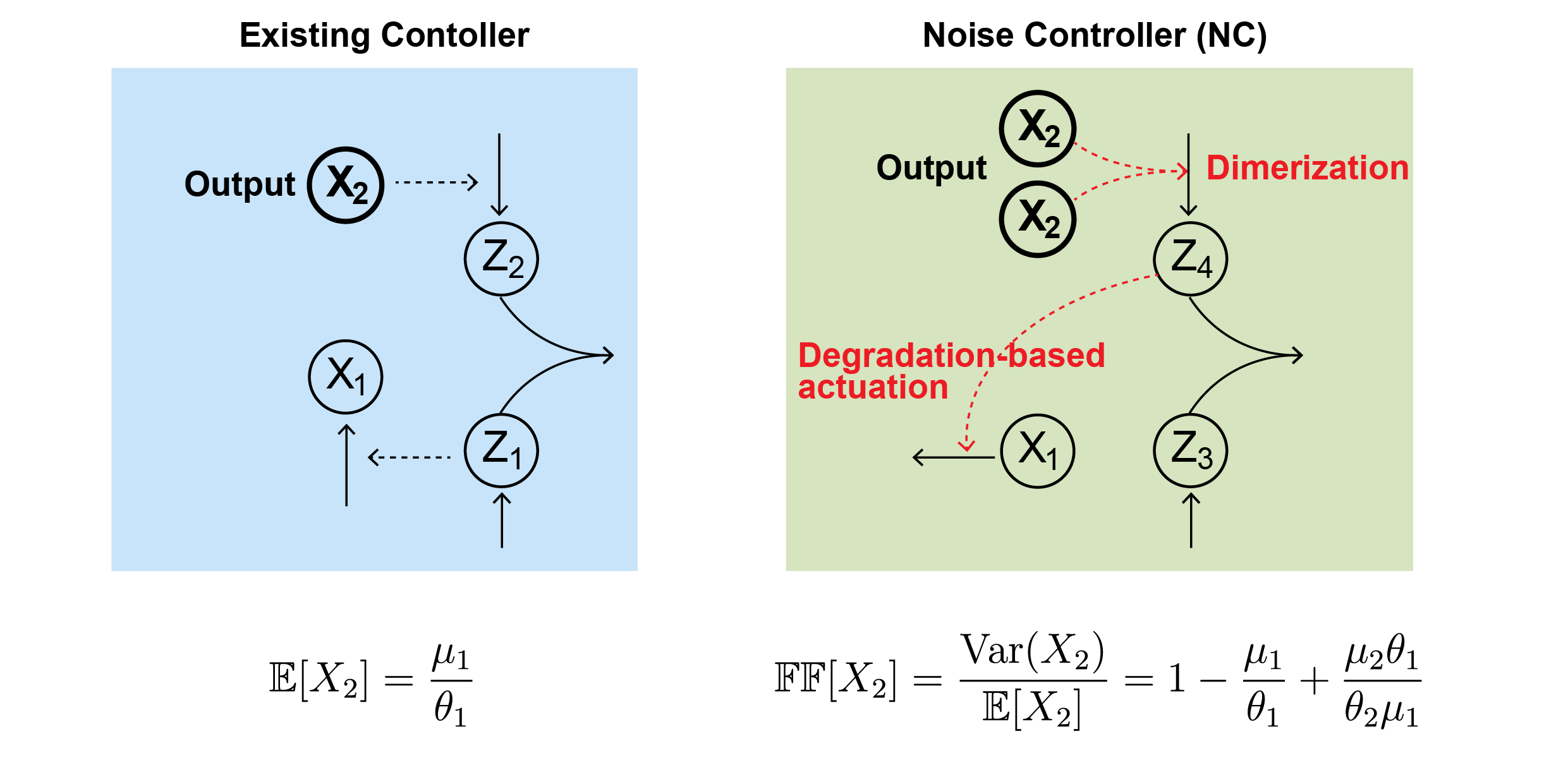

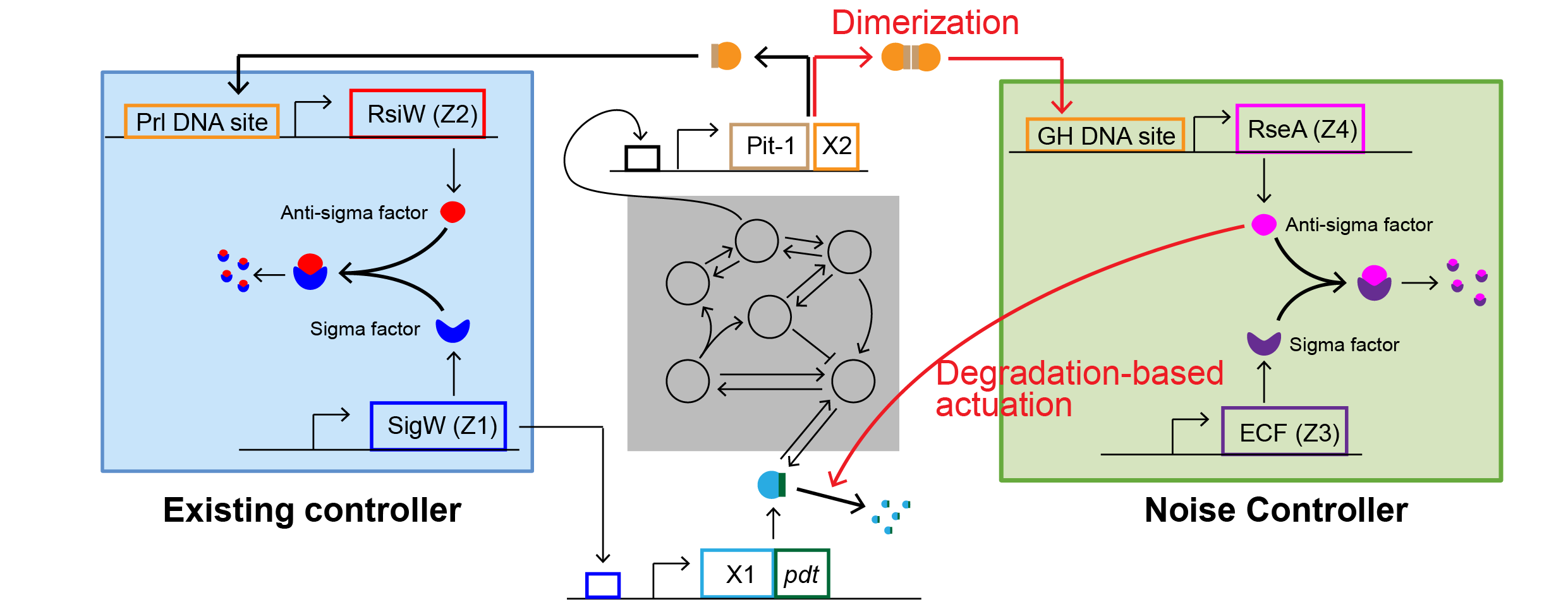

“Instead of accepting that limit, our researchers designed a second layer of control that targets noise directly. The NC does not just sense how much protein is present. It aims to sense variation itself, using a statistic tied to the second moment of protein levels,” Professor KIM Jae Kyoung, the corresponding author, told The Brighter Side of News.

“Our proposed mechanism relies on two ideas. One is dimerization, when two copies of a protein bind together. The other is degradation-based actuation, which means actively breaking down specific proteins to push the system back toward steadier behavior. In the model, these features let the system “measure” and reduce its own variability,” he continued.

The result is what the researchers call “Noise Robust Perfect Adaptation,” or Noise RPA. In this regime, both the average protein level and the size of fluctuations stay stable, even after changes in conditions.

The study uses the Fano factor as a yardstick for noise. It links variance to the mean. In their simulations, the combined control strategy can reduce noise down to a Fano factor of 1.

The team treats that value as a meaningful floor for this approach. When they tried to set a target below 1, the control system stopped behaving well. Key controller components grew without settling, and regulation broke down.

They also tested whether the approach depended on fine-tuned settings. In their simulations, noise reduction to a Fano factor of 1 held up across wide parameter changes. It also worked across different kinds of reaction networks, including systems with bimolecular steps and dimerization.

That robustness matters because biological parts rarely behave exactly as designed. A controller that only works in one narrow setting would have limited value in real cells.

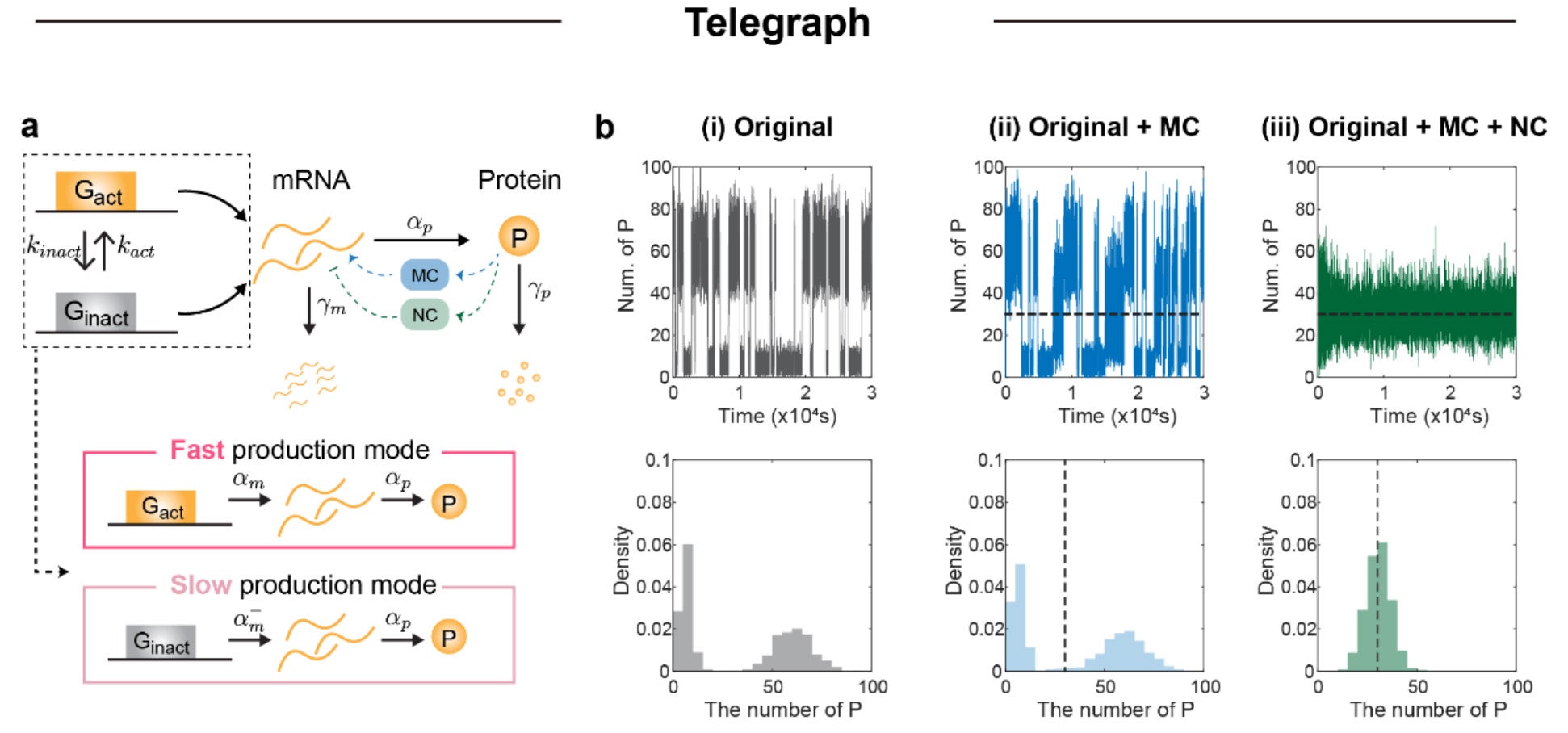

Noise can create more than scatter. It can split a population into two distinct groups, a pattern called bimodality. In that case, cells can cluster in a “low” state and a “high” state, even under the same conditions.

To test this, the researchers used a classic switching model of gene expression, where a gene flips between active and inactive states. A mean-only controller could hold the average steady, but it did not stop the split. When the NC was added, the simulated behavior shifted toward a single stable group around the target.

The team also tested a more concrete scenario: DNA repair in E. coli. In this system, methyl methanesulfonate damages DNA. The Ada protein helps repair that damage and helps turn on more of its own production. But the loop can fail if a cell starts with zero Ada molecules.

In standard simulations, about 20% of bacteria failed to activate repair because of noise. With the Noise Controller applied, the simulated failure rate dropped from 20% to 7%. The model also showed a steep drop in the chance of cells sitting at a zero-Ada state.

The researchers frame that as the practical promise of noise control. If outliers can be reduced, fewer cells may slip into the rare states that drive failure.

“This research demonstrates that cellular noise; often dismissed as luck or unavoidable randomness; can be brought into the realm of precise mathematical control,” said Professor Kyoung. “We expect this technology to play a key role in developing smart microbes and overcoming drug resistance in cancer therapy.”

Professor KIM Jinsu, co-corresponding author, added, “This achievement shows the power of mathematical modeling, starting from theoretical equations to design a mechanism that solves a fundamental biological problem.”

The core takeaway is that treatment failure may not always stem from genetic resistance. It can also come from random molecular swings that push a few cells into protected states. By offering a way to reduce those swings in theory, the work points to strategies that could make therapies more reliable. If future lab studies can translate these designs into real gene circuits, researchers may be able to shrink the fraction of “survivor” cells that restart tumors or infections.

The study also offers a roadmap for synthetic biology. Many engineered microbes work well on average but behave unevenly cell to cell. A noise-focused controller could help build microbial systems that act more consistently, improving applications from biomanufacturing to environmental sensing.

More broadly, the framework clarifies what control can achieve, and where hard limits appear, which can guide smarter experiments and safer designs.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New study provides a key breakthrough in cancer therapy and synthetic biology appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.