Astronomers from the University of Geneva, working with colleagues in Canada and the United States, have captured the clearest view yet of an exoplanet losing its atmosphere into space. Using the James Webb Space Telescope, researchers observed vast clouds of helium escaping from the planet WASP-107 b. Their findings were published in Nature Astronomy and modeled using tools developed at the University of Geneva and the National Centre of Competence in Research PlanetS.

The observations offer rare insight into atmospheric escape, a process that shapes how planets change over time. While Earth loses only a small amount of gas each second, planets that orbit close to their stars can lose their atmospheres far more quickly. This loss can alter a planet’s size, chemistry, and long-term survival.

WASP-107 b orbits a small, cool star more than 210 light-years away. It completes one orbit every 5.72 days, placing it far closer to its star than Mercury is to the Sun. The intense heat drives gas high into space, where it can escape the planet’s gravity.

Discovered in 2017, WASP-107 b belongs to a rare class known as “super-puff” exoplanets. The planet is almost as large as Jupiter but has only about one-tenth of its mass. This gives it an extremely low density and a swollen atmosphere that is loosely held by gravity.

Because of this structure, WASP-107 b has long been suspected of losing gas. Earlier observations with the Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based instruments detected helium and even a comet-like tail trailing the planet. The new Webb data show that the escaping atmosphere is far larger and more complex than scientists once thought.

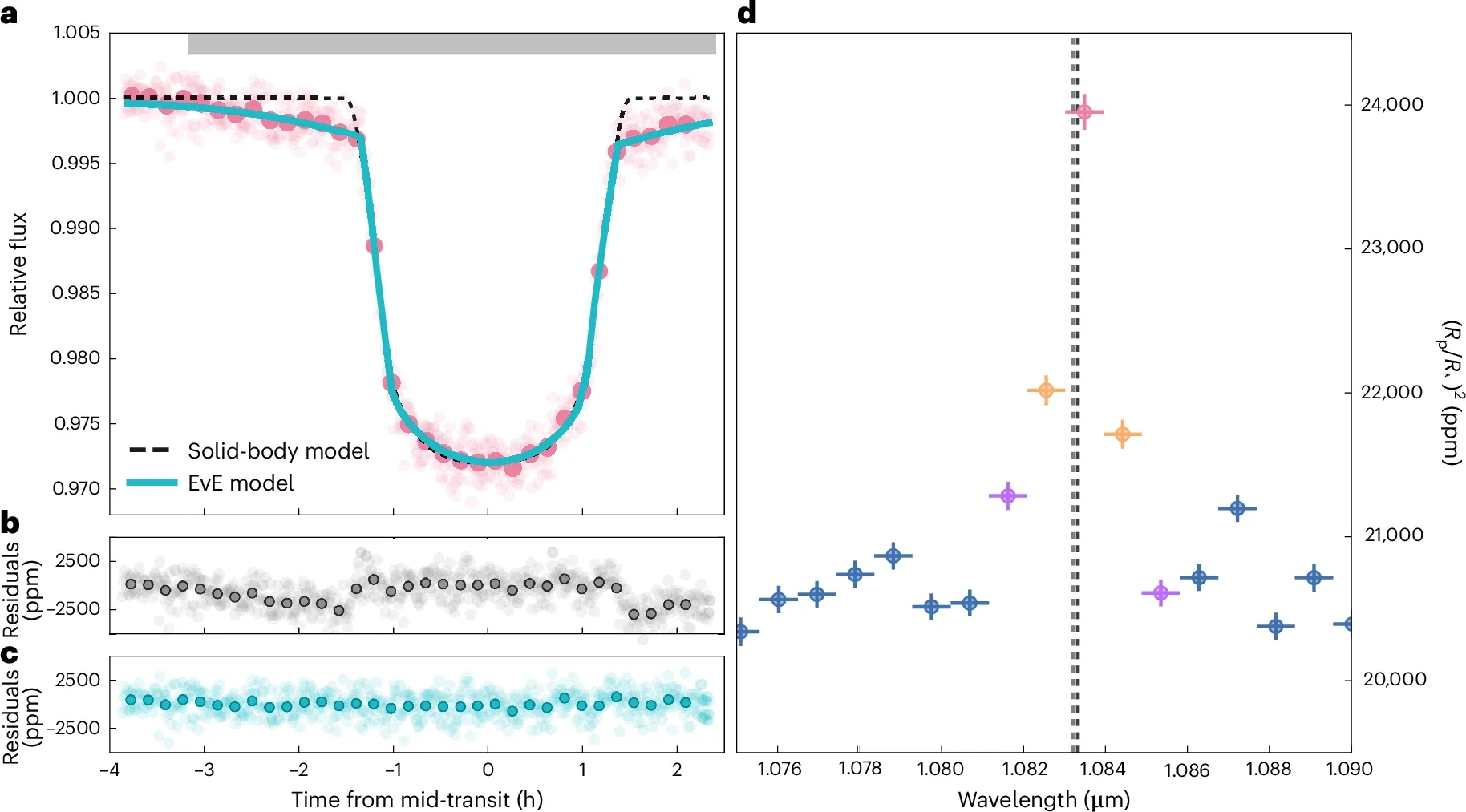

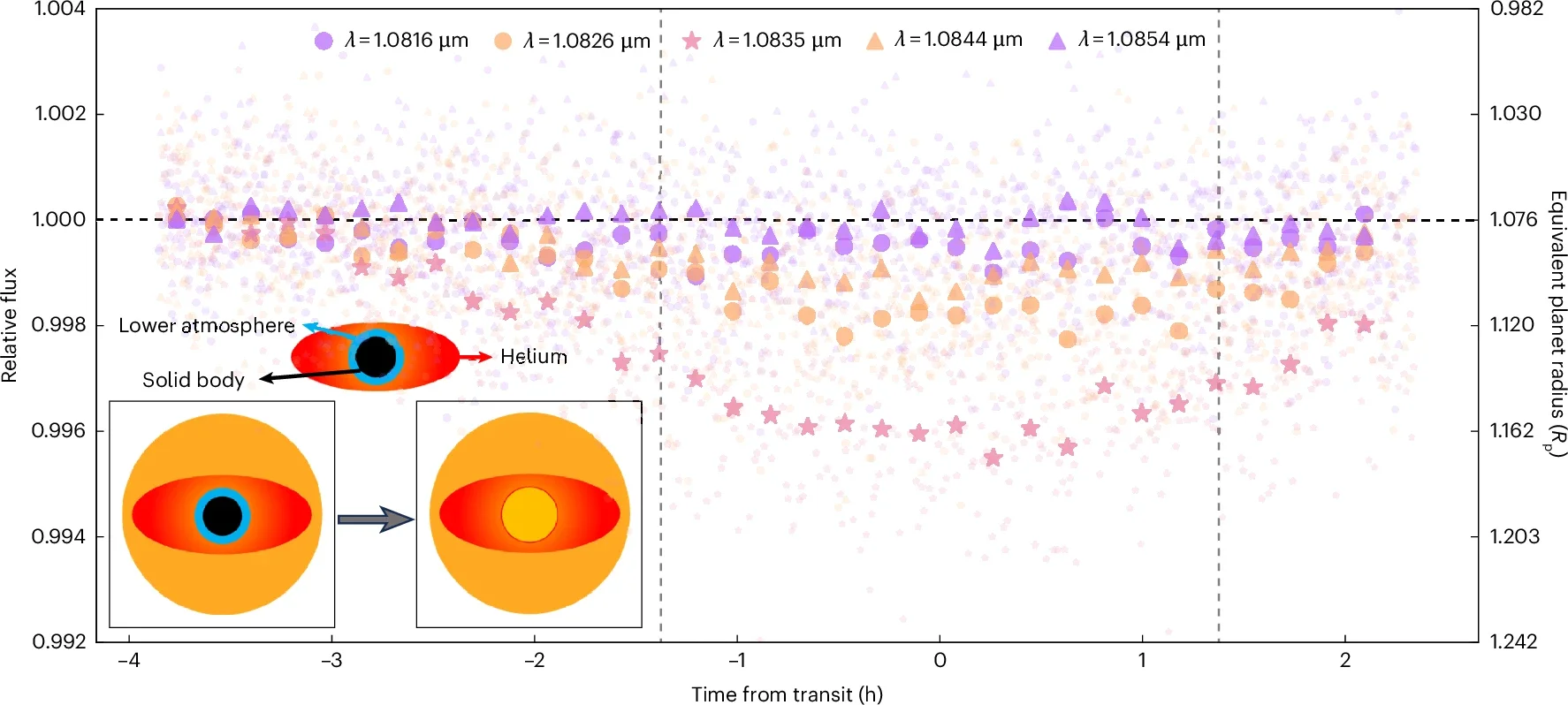

Using Webb’s Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, the team observed a full, uninterrupted transit lasting more than six hours. This included over two hours before the planet crossed its star, the entire transit, and more than an hour afterward. That continuous view proved essential.

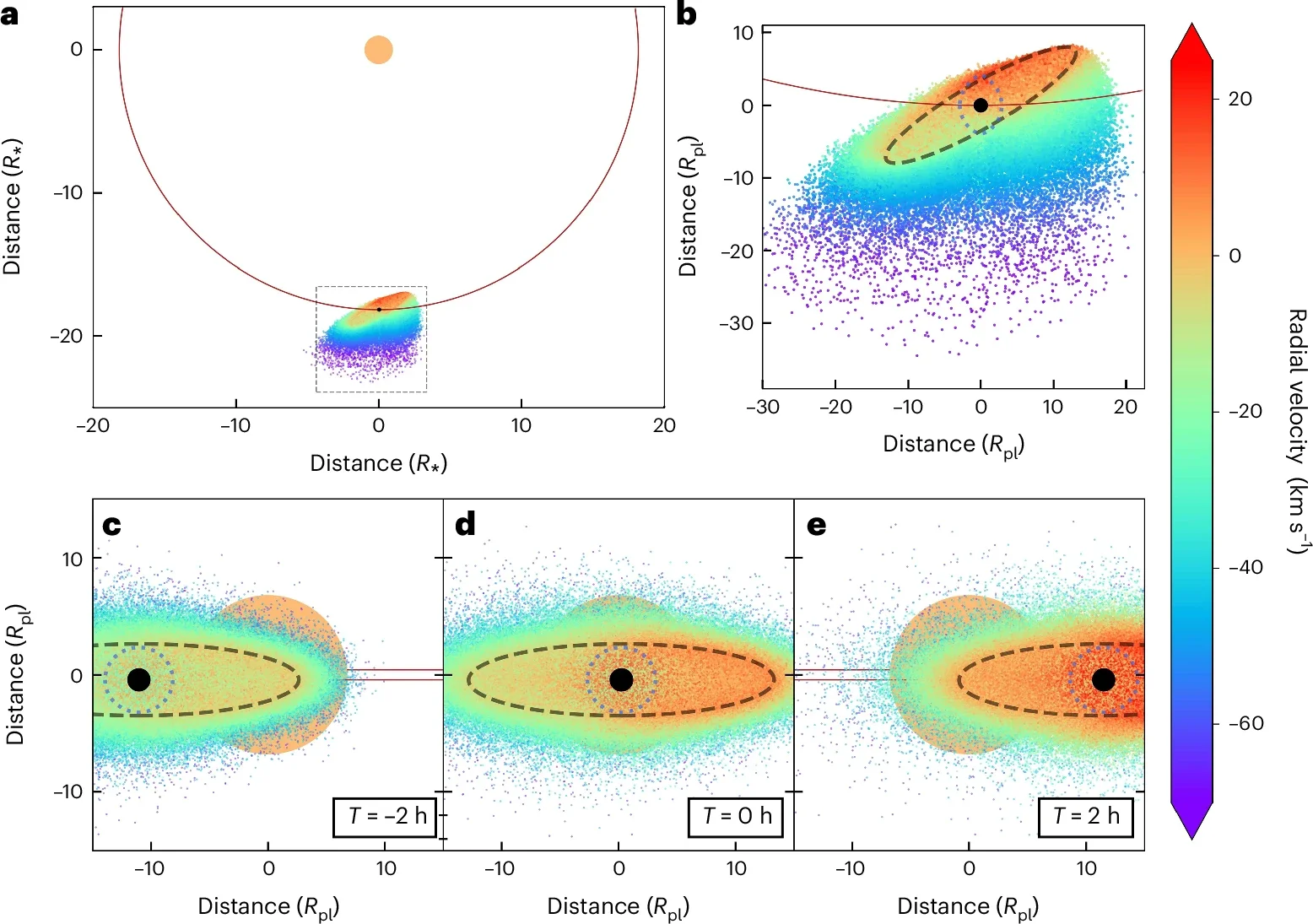

The observations revealed helium absorption not only during the transit, but also long before and after it. This means the planet’s atmosphere stretches far beyond its visible edge, forming a giant envelope of gas that both leads and trails the planet along its orbit.

“Our atmospheric escape models confirm the presence of helium flows, both ahead and behind the planet, extending in the direction of its orbital motion to nearly ten times the planet’s radius,” said Yann Carteret, a doctoral student in astronomy at the University of Geneva and a co-author of the study.

The helium signal was detected with extremely high confidence. Before the planet even began crossing the star, the helium absorption reached a significance of 17 sigma. After the transit, it reached 19 sigma. These signals could not be explained by stellar activity or instrument noise.

“To understand the data, our research team used advanced simulations to recreate the planet’s upper atmosphere. A simple, spherical atmosphere could not explain the long-lasting helium signal. Helium atoms in this state survive only about two hours, meaning the gas must stay close to the planet,” Carteret shared with The Brighter Side of News.

The best model describes an elongated thermosphere shaped like a stretched cloud. It extends between 10 and 18 planetary radii both ahead of and behind WASP-107 b. The gas reaches temperatures near 7,000 kelvin and escapes at a rate of roughly one trillion grams per second.

The helium itself accounts for nearly a million grams per second of that loss. Over billions of years, this steady outflow can strip away a large fraction of the planet’s mass.

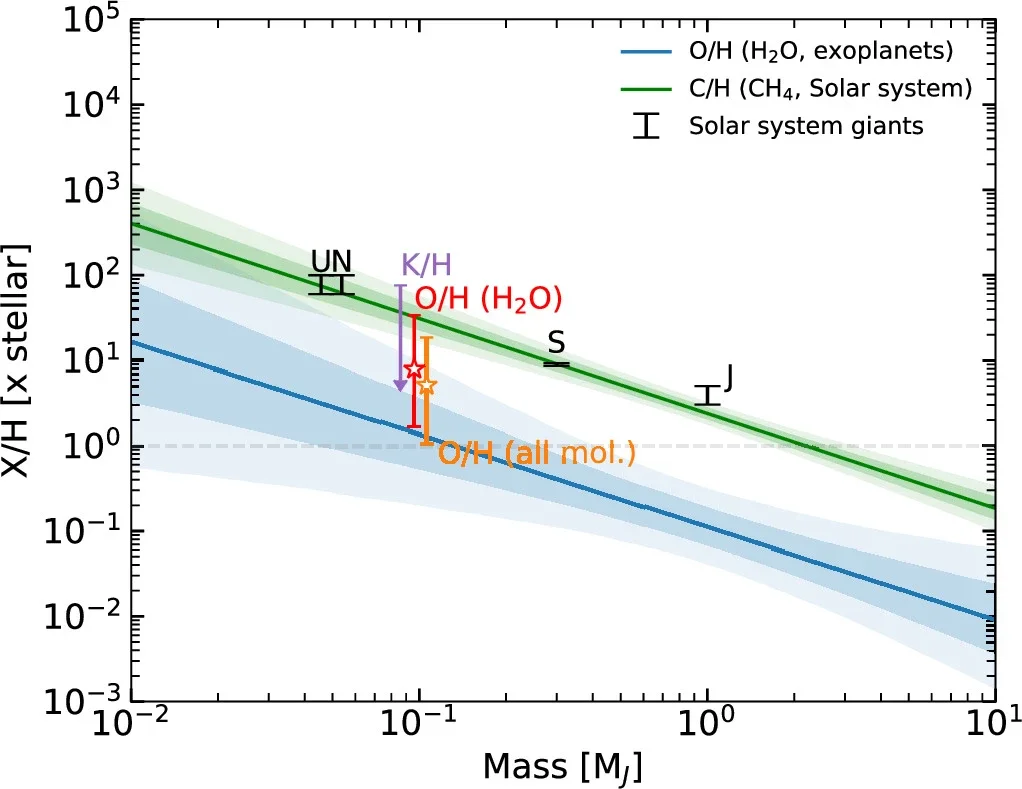

Beyond helium, Webb detected water vapor and traces of carbon-based molecules in the atmosphere. Carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and ammonia were present, while methane was notably absent. The telescope’s sensitivity makes that absence meaningful.

These chemical fingerprints suggest that the planet did not form where it currently orbits. Instead, the evidence points to formation farther from the star, followed by inward migration. As the planet moved closer, heat inflated its atmosphere and triggered intense gas loss.

“Observing and modeling atmospheric escape is a major research area at the UNIGE Department of Astronomy because it is thought to be responsible for some of the characteristics observed in the exoplanet population,” said Vincent Bourrier, senior lecturer and research fellow at the University of Geneva and a co-author of the study.

The team also addressed a common challenge in exoplanet research: contamination from the star itself. Dark star spots can mimic atmospheric signals if not properly accounted for.

By applying multiple atmospheric models, the researchers showed that earlier estimates of water abundance were too high. Once stellar effects were removed, the planet’s water content dropped sharply. This correction reduced previous estimates by a factor of about 40.

The study also placed tight limits on other elements, including ammonia and potassium. These low levels match expectations for an atmosphere with strong vertical mixing and high metal content.

This research changes how scientists understand atmospheric escape on close-in planets. Continuous observations show that short or incomplete measurements can miss much of an escaping atmosphere. Many exoplanets may be losing far more gas than previously believed.

The findings also help explain why some planets appear bloated while others shrink or lose their atmospheres entirely. Understanding these processes improves models of planet formation and survival, including conditions that may allow rocky worlds to retain water.

“On Earth, atmospheric escape is too weak to drastically influence our planet. But it would be responsible for the absence of water on our close neighbor, Venus,” Bourrier said. “It is therefore essential to fully understand the mechanisms at work in this phenomenon, which could erode the atmosphere of certain rocky exoplanets.”

In the long term, this work helps scientists identify which distant worlds might remain stable enough to support complex chemistry or life.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post JWST observations reveal massive helium clouds escaping from exoplanet WASP-107 b appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.