Nature’s most dazzling colors can be strangely rare. Walk through a park or forest and you see greens, yellows and reds that feel soft to the eye. Most of those tones are matte. Only now and then do you spot a buttercup petal or beetle shell that flashes like polished metal.

That contrast caught the attention of evolutionary biologist Casper van der Kooi. He wanted to know why glossy colors are uncommon, and what that means for the animals that rely on color to survive. So he turned to bees, artificial flowers and a simple question that leads to a surprisingly deep answer.

In your mind, picture a daisy, a great tit’s feathers or a small tree frog. Their colors stay steady as you move around them. Matte surfaces scatter light in many directions, so the shade looks almost the same from every angle and in most lighting.

“Many colours serve as signals, for example, to attract pollinators or a mate,” Van der Kooi said. Those signals work best when they are predictable in space and time. If a flower petal always looks the same shade of yellow, a bee can learn that this color means nectar and pollen.

Matte colors do that job well. They send a simple, stable message: here is food, here is a partner, here is a warning. Evolution often favors that kind of reliability.

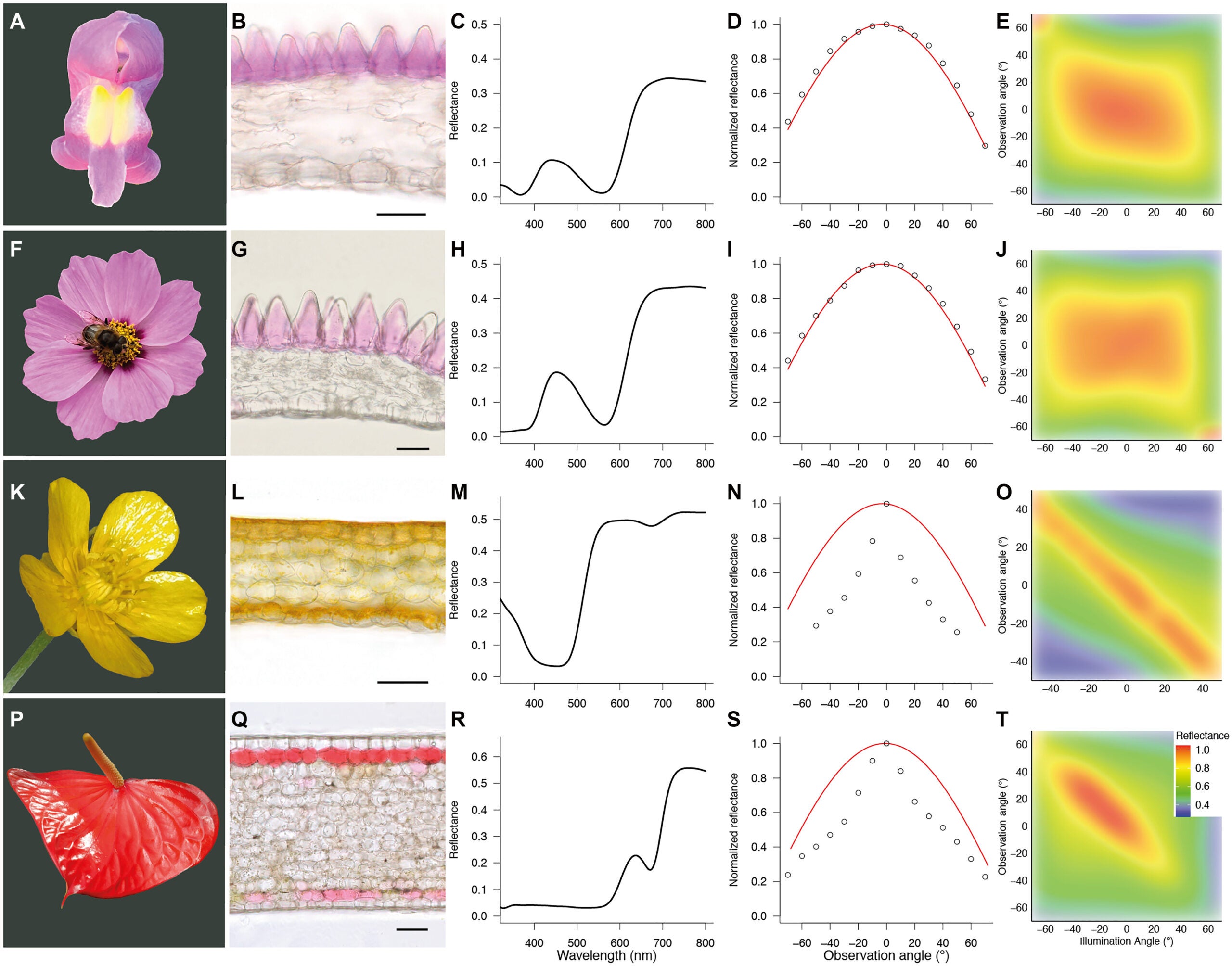

Yet the natural world does not only speak in soft tones. You also see glossy buttercups, beetles with metallic shells and butterflies that flash bright blue when they tilt in the sun. These shiny colors respond to light in a very different way.

“These shiny colours have a dynamic quality: how you perceive them depends on the angle of observation, the level of illumination, and the time of day,” Van der Kooi explained. In other words, gloss is alive to movement. A slight change in where you stand, or where the sun sits, can flip a petal from dull to dazzling.

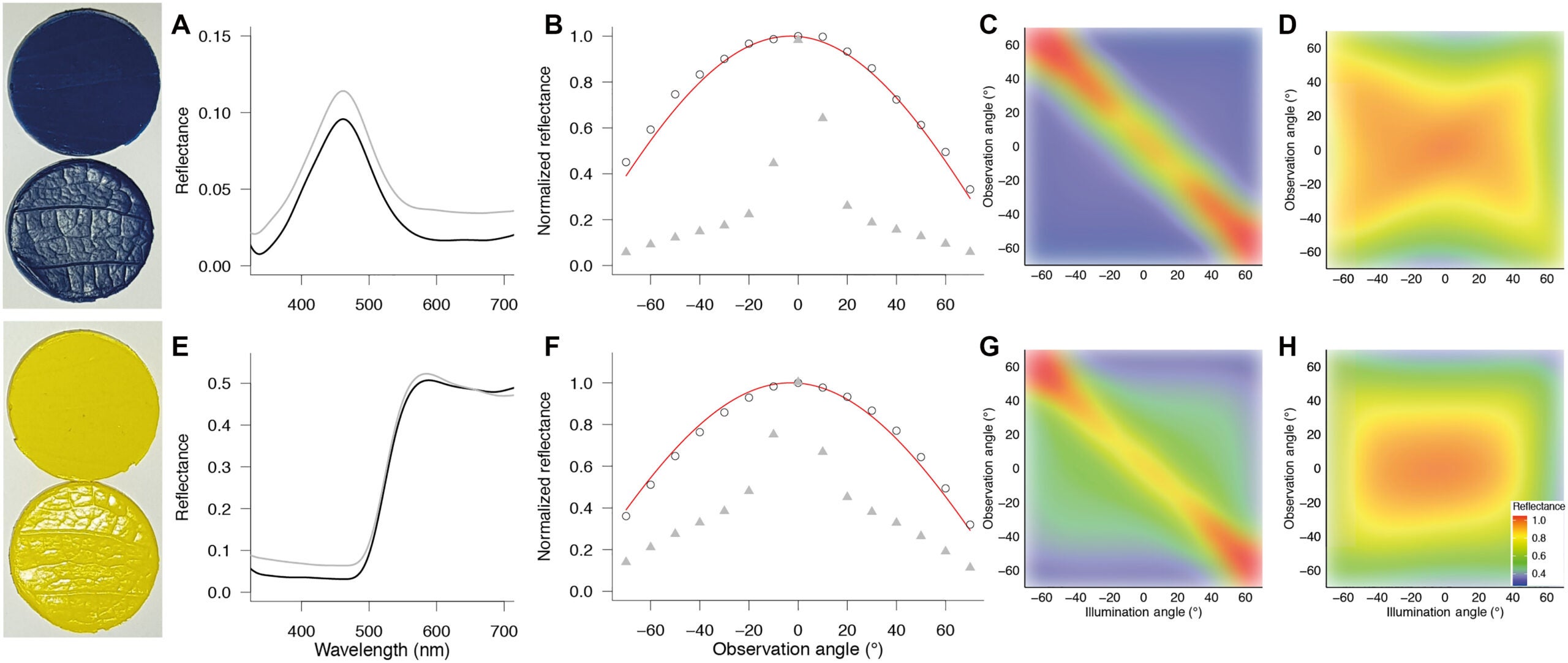

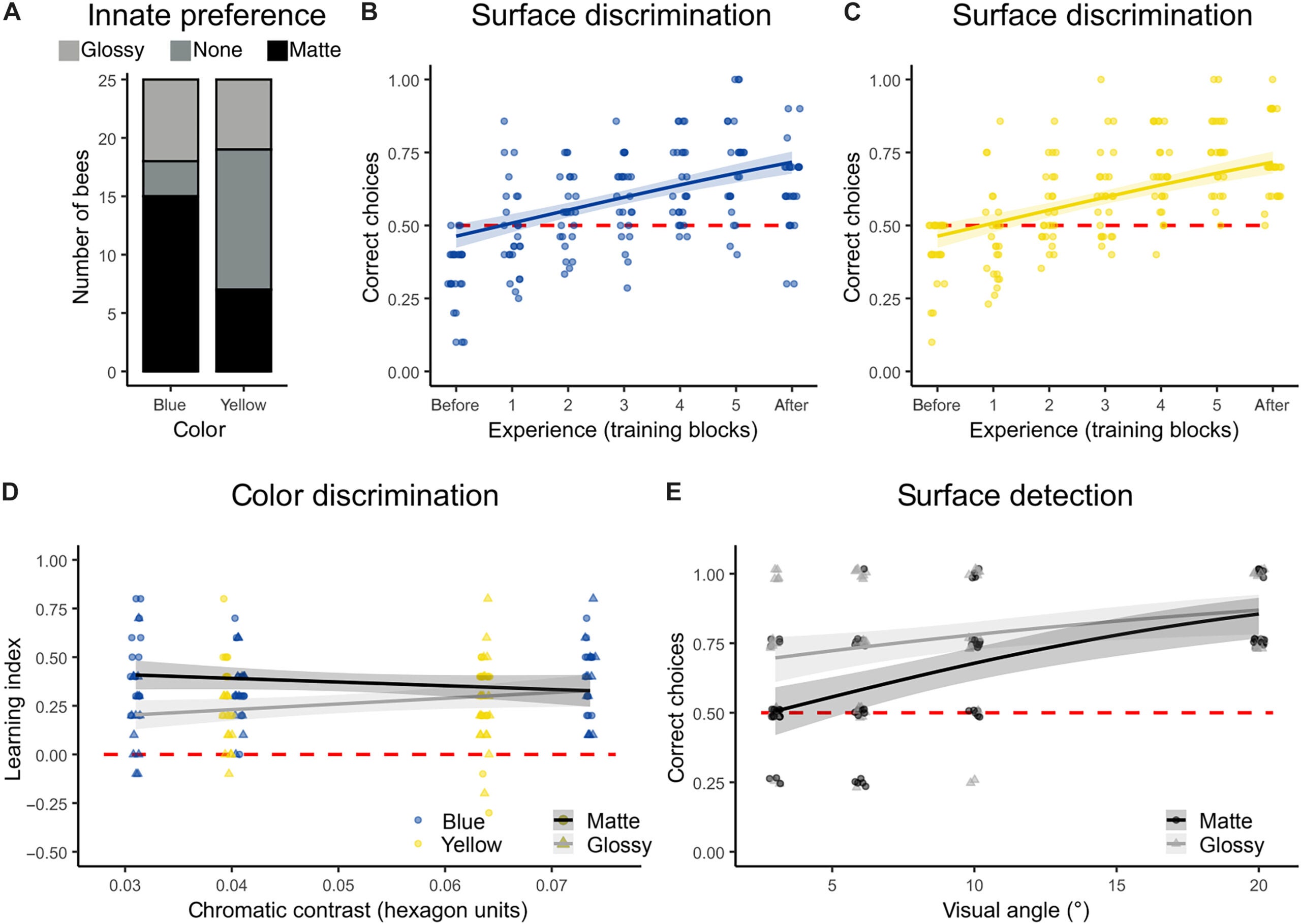

To test how that shimmer affects bees, Van der Kooi and his team built artificial flowers with either matte or glossy surfaces. They then released bumblebees into large cages and watched how often the insects visited each type.

From far away, the result was clear. Shiny “flowers” popped out of the background. Their flashes of reflected light worked like a lighthouse beam or the flash of blue on an emergency vehicle. To a fast moving bee searching for food, that kind of bright cue can be a powerful guide.

The story changes as the bee gets close. At short range, gloss becomes a problem rather than a help.

“At close range, their shininess will make them more difficult to see in detail,” Van der Kooi said. He compared it to reading a glossy magazine out in full sun. The light catches the shiny page and you lose the shape of the letters in the glare.

The same thing happens to a bee approaching a glossy petal. The reflected light can wash out fine detail and color contrast. That makes it harder for the insect to judge exactly where to land or how rich the bloom is. The signal becomes bright but fuzzy.

“So, there is a trade-off, which explains why dynamic, shiny colours are rarer than static, matte ones,” he said. “It’s a visual trade-off.” Shiny petals help you stand out at a distance, but they make close work more difficult.

This trade-off gives you a fresh way to look at the flowers and animals around you. If a plant depends on repeat visits from bees or other pollinators, clear and consistent colors close up can matter more than attention grabbing flashes from far away.

Matte petals offer that kind of reliability. They tell a bee, in a sense, “when you get here, you will see exactly what you expect.” Over many generations, that kind of honest, stable signal can beat out the more dramatic but confusing shine.

Shiny signals may still have their place. In cluttered habitats, bright flashes could help insects find flowers hidden among leaves. In other cases, dynamic shine might confuse predators or help insects recognize each other. But for most plants, evolution seems to favor the simple, matte message.

Understanding how bees see glossy and matte surfaces does not only satisfy curiosity. It also gives you practical tools.

“We could use this new knowledge to build better traps for pest insects, and advise engineers on how to prevent bees from flying to solar panels instead of flowers,” Van der Kooi told The Brighter Side of News.

If shiny panels lure bees away from crops, designers could change the surface texture or coating to cut those misleading flashes. At the same time, farmers or public health workers might choose extra glossy traps to attract pest insects from far away, then use matte details or patterns to guide them once they arrive.

The lesson is simple but powerful. When you shape how a surface reflects light, you shape how an animal experiences the world.

This research reminds you that color is not just about pigment. It is also about texture, angle and the way light bounces off tiny structures. A buttercup’s shine, a beetle’s metallic shell and a glossy magazine page all play with the same physics.

For bees, play has real stakes. A clear signal can mean a full stomach and a successful trip back to the hive. A confusing glare can waste time and energy. Over millions of years, small differences in how petals reflect and scatter light have helped decide which flowers fill your fields and gardens today.

The next time a shiny petal catches your eye, it carries a quiet story. It is not only a pretty effect. It is a compromise between standing out and staying readable, between a bright shout and a steady, soft voice.

This work offers a concrete guide for anyone who designs surfaces that insects see and respond to. By showing that gloss helps detection at long range but hurts detail at close range, it gives engineers a way to tune traps for pest insects, pollinator friendly structures and even protective barriers.

Crop managers can use highly glossy patterns on traps to draw in pests from far away, then add matte elements that keep the insects focused once they arrive. Solar panel designers and urban planners can reduce unwanted bee visits by breaking up large shiny fields with matte textures or different reflective properties.

For scientists, the study opens new paths in visual ecology. Future research can test how other pollinators respond to gloss, how different levels of shine change behavior and how petals evolve under changing light conditions in cities and farms.

Over time, this knowledge can support both biodiversity and agriculture, helping you design landscapes that work better for people and for the insects that keep ecosystems running.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science Advances.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Why shiny flowers are rare: bee vision reveals a hidden visual trade-off appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.