Deep inside the brain, every thought and memory begins with a burst of electrical activity. For years, scientists have tried to watch that activity in real time by shining lasers into the brain. Now a new tool lets brain cells light themselves from within, turning them into tiny living lanterns.

About a decade ago, a team of neuroscientists started asking a bold question: “What if we could light up the brain from the inside?” said Christopher Moore, a professor of brain science at Brown University. Instead of blasting tissue with outside light, they wondered if neurons could make their own glow.

That idea led to the launch of the Bioluminescence Hub at Brown’s Carney Institute for Brain Science in 2017, supported by a major National Science Foundation grant. The hub brought together Moore, institute director Diane Lipscombe, Ute Hochgeschwender at Central Michigan University and molecular engineer Nathan Shaner at the University of California San Diego.

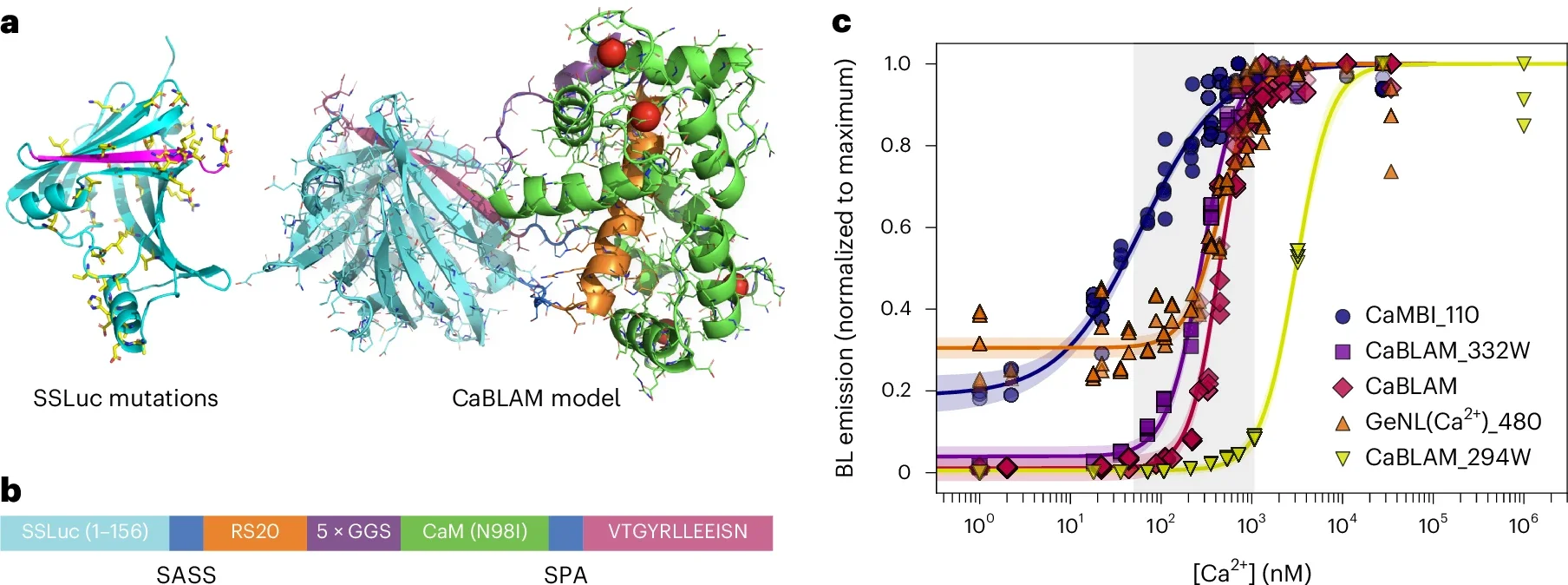

Their shared goal was simple to say and hard to pull off: give nervous system cells the power to both make light and respond to it. In a study published in Nature Methods, the team reports one of the most important results of that collaboration so far, a tool called the Ca2+ BioLuminescence Activity Monitor, or CaBLAM.

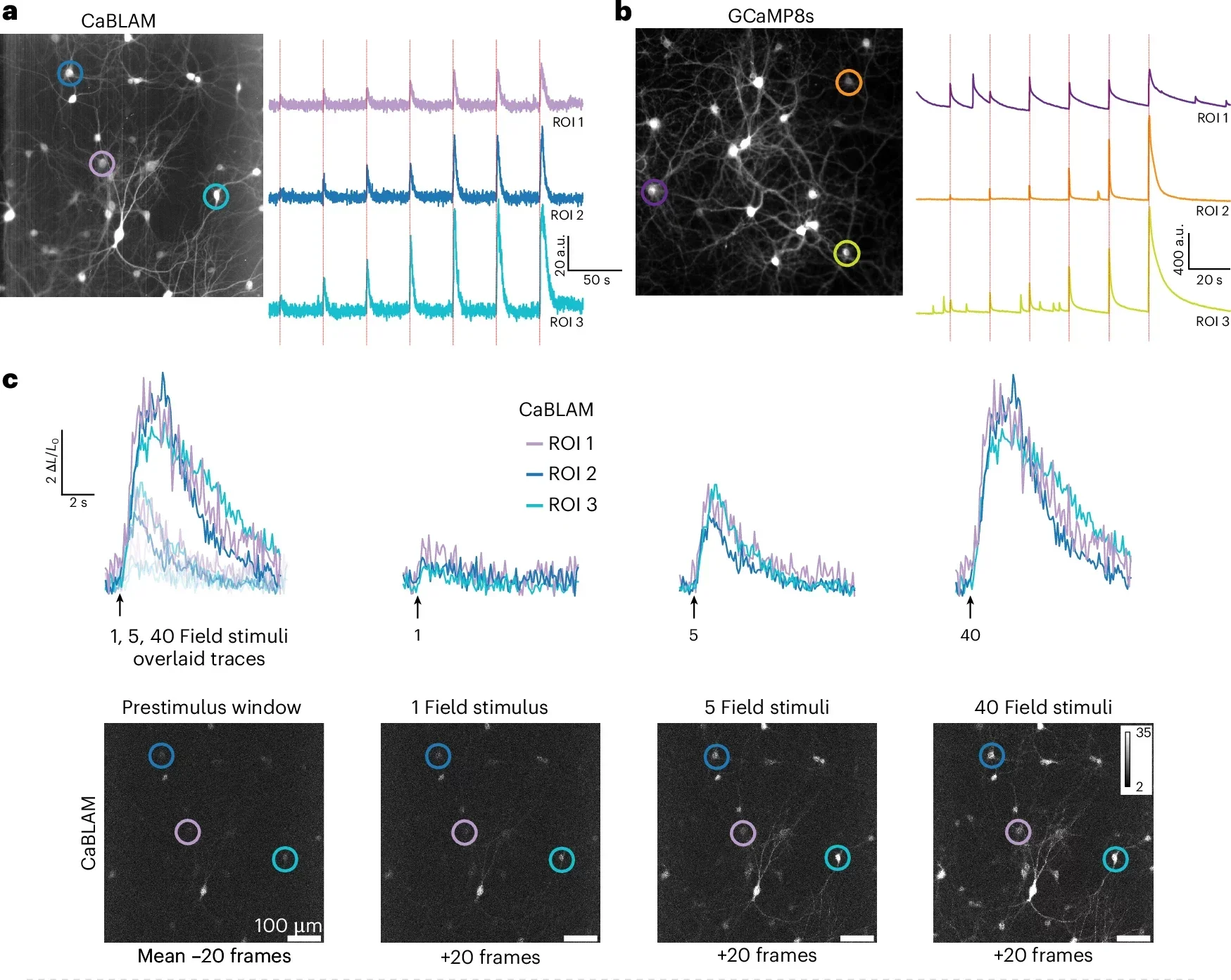

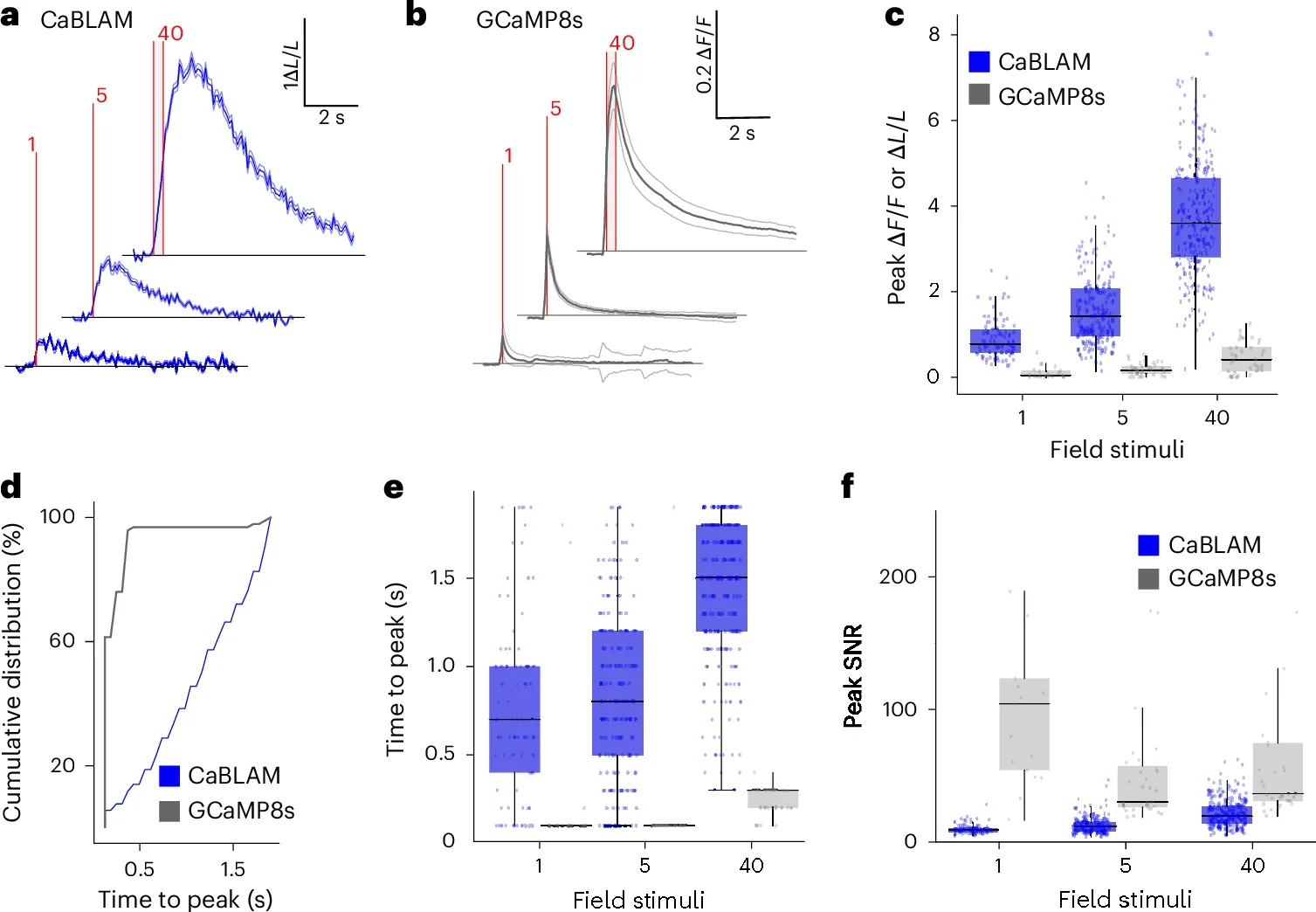

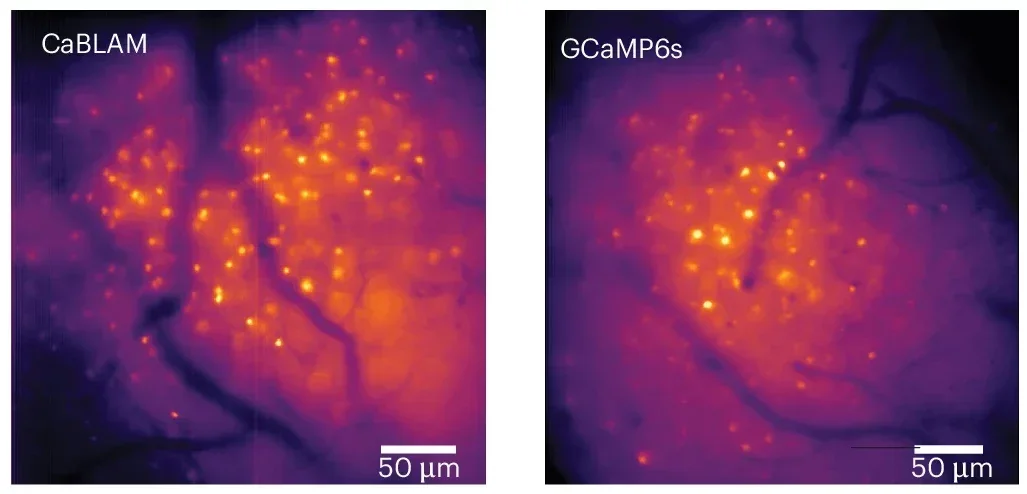

CaBLAM lets researchers see the activity of single brain cells, and even parts of those cells, at high speed in living animals. It works for hours at a time in mice and zebrafish and does all of this without a single external laser beam.

Instead of using fluorescent probes that need strong light from outside, CaBLAM relies on bioluminescence, the same style of light that fireflies use. In bioluminescence, an enzyme breaks down a small molecule and releases light as part of the reaction.

Shaner, an associate professor in neuroscience and pharmacology at UC San Diego, led the effort to design the molecule that became CaBLAM. “CaBLAM is a really amazing molecule that Nathan created,” Moore said. “It lives up to its name.”

CaBLAM is built so that its glow tracks calcium, the key signaling ion that surges inside neurons when they fire. When calcium levels rise in a cell, CaBLAM shines more brightly; when they fall, the light fades. That simple shift lets scientists turn invisible electrical activity into something they can record like a movie.

“The current paper is exciting for a lot of reasons,” Moore said. “These new molecules have provided, for the first time, the ability to see single cells independently activated, almost as if you’re using a very special, sensitive movie camera to record brain activity while it’s happening.”

Before CaBLAM, most labs used fluorescence based calcium indicators. With fluorescence, you shine light in and wait for a different color to come back out. “In the way fluorescence works, you shine light beams at something, and you get a different wavelength of light beams back,” Moore explained.

That approach has helped map brain circuits for years, but it comes with serious tradeoffs. Strong light can damage cells over time. Fluorescent molecules can burn out, a problem called photobleaching, which cuts recordings short. The hardware that delivers light into the brain, such as lasers and optical fibers, adds bulk and often requires invasive surgeries.

Bioluminescence avoids many of those hurdles. Because the light comes from chemical reactions inside the cell, there is no need to blast tissue with bright beams. That means no photobleaching and no light induced toxicity, which makes CaBLAM gentler on brain health and better suited for long experiments.

The glow is clearer too. “Brain tissue already glows faintly on its own when hit by external light, creating background noise,” Shaner said. “On top of that, brain tissue scatters light, blurring both the light going in and the signal coming back out. This makes images dimmer, fuzzier, and harder to see deep inside the brain. The brain does not naturally produce bioluminescence, so when engineered neurons glow on their own, they stand out against a dark background with almost no interference.”

He likens it to giving cells their own headlights. With bioluminescence, you only need to watch the light that comes out, which remains visible even after it scatters through thick tissue.

For decades, researchers had dreamed about using bioluminescence to measure brain activity. The obstacle was brightness. Earlier systems simply did not produce enough light to catch fast, subtle changes in living brains.

CaBLAM breaks through that barrier. In the new study, the team captures the activity of single neurons and even subcellular compartments in live lab animals. They show that CaBLAM can follow those signals for at least five continuous hours, something that would be nearly impossible with traditional fluorescent tools.

“For studying complex behavior or learning, bioluminescence allows one to capture the entire process, with less hardware involved,” Moore told The Brighter Side of News. “Instead of juggling lasers, mirrors and fibers, researchers can implant a simple sensor, supply the chemical fuel and then watch activity unfold,” he continued.

That flexibility opens new doors if you want to track changes across long training sessions, sleep cycles or disease progression. It also makes it easier to image multiple brain regions at once, since you do not have to route separate light paths into each location.

CaBLAM is just one piece of a larger vision for the Bioluminescence Hub. Moore’s group and their collaborators are building ways not only to watch neurons with light, but also to let them talk to each other using light signals.

One project uses a living cell to send a flash of bioluminescent light that a nearby cell can detect and translate into electrical activity. Moore calls this idea “rewiring the brain with light.” Another set of tools uses calcium itself to control cellular activity, turning the ion that usually reports activity into a switch that can drive it.

As those concepts came together, the team realized everything depended on better calcium sensors. They needed brighter, faster, more reliable bioluminescent molecules. That need pushed CaBLAM to the center of the hub’s work. “We made sure that as a center that’s trying to push the field forward, we created the necessary component pieces,” Moore said.

He also hopes CaBLAM will travel beyond the brain. Because calcium shapes activity in muscle, heart, gut and immune cells, the same technology could help you see how different parts of the body work together in real time. “This advance allows a whole new range of options for seeing how the brain and body work,” Moore said, “including tracking activity in multiple parts of the body at once.”

None of this happened in isolation. At least 34 researchers across Brown, Central Michigan University, UC San Diego, the University of California Los Angeles and New York University contributed to the project. Funding came from the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Paul G. Allen Family Foundation.

CaBLAM gives scientists a safer and longer lasting way to watch live brain activity, which could reshape how research on learning, memory and disease is done. Because the tool does not require harsh light or bulky lasers, labs can follow neurons across hours or even days and still keep tissue healthy. That makes it easier to study slow processes, such as recovery after injury or the progression of neurological disorders.

You can also apply this method to many organs that rely on calcium signals, from the heart to the immune system. In the long run, CaBLAM and related tools may help map how entire networks of cells coordinate during behavior, illness or treatment. The same bioluminescent technology could support new therapies that use light patterns to steer activity in damaged circuits, without adding heat or causing extra harm.

Most importantly, the work shows that bioluminescent tools can finally reach the speed and detail needed for modern neuroscience. As these molecules improve, they may reduce the need for high power lasers in basic research, cut costs for labs and lower the risk to animals in experiments. That combination of technical power and gentler impact has the potential to benefit both science and human health.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Methods.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post New bioluminescent tool lets scientists watch live neural activity for hours appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.