Silent cells deep in your spinal cord may hold a surprising key to healing after devastating injuries and brain disease. A new study from Cedars-Sinai, reveals that support cells called astrocytes do far more than watch from the sidelines. They help coordinate cleanup and repair across long stretches of the central nervous system, and they do it from far away.

Astrocytes sit throughout your brain and spinal cord, wrapping around nerve fibers and blood vessels. They help keep neurons healthy, balance chemicals and support the flow of electrical signals that let you move, feel and think.

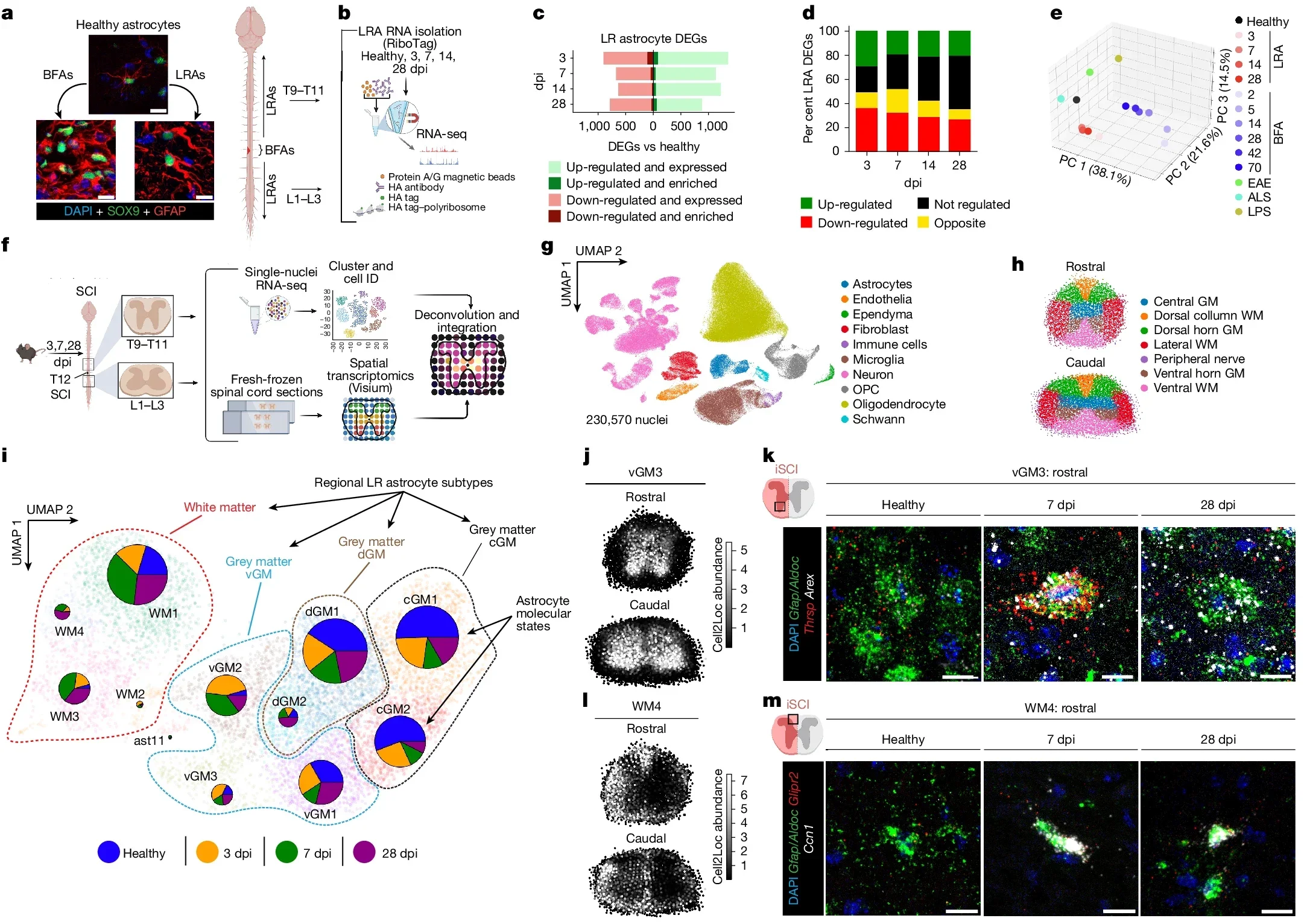

After an injury, scientists have mostly focused on astrocytes right at the damage site. Those local cells form a scar and shield nearby tissue. Joshua Burda, PhD, a neuroscientist at Cedars-Sinai, and his team took a different view.

“We discovered that astrocytes far from the site of an injury actually help drive spinal cord repair,” said Burda, assistant professor of Biomedical Sciences and Neurology and senior author of the study.

The investigators named these distant helpers “lesion-remote astrocytes,” or LRAs. They identified several subtypes and showed that at least one group can sense injury from afar, then respond in a very specific way.

Your spinal cord is a thick bundle of nerve tissue that carries signals between your brain and body. Gray matter in the center holds nerve cell bodies and astrocytes. White matter around it contains long nerve fibers, wrapped in insulation, that run up and down the cord.

When the spinal cord is injured, many of those long fibers snap. The broken pieces die and turn into fatty debris. In most organs, inflammation stays close to the wound. In the spinal cord, damage spreads along the length of those fibers, and so does inflammation.

That extra reach makes cleanup much harder. Debris can linger far from the original injury site, clogging pathways that signals need for movement and sensation. The Cedars-Sinai team wanted to know how the nervous system handles that challenge.

“In experiments with mice, our team found that LRAs in regions away from the core injury become active and support repair. When we examined spinal cord tissue from people with spinal cord injury, we saw signs of the same response,” Burda told The Brighter Side of News.

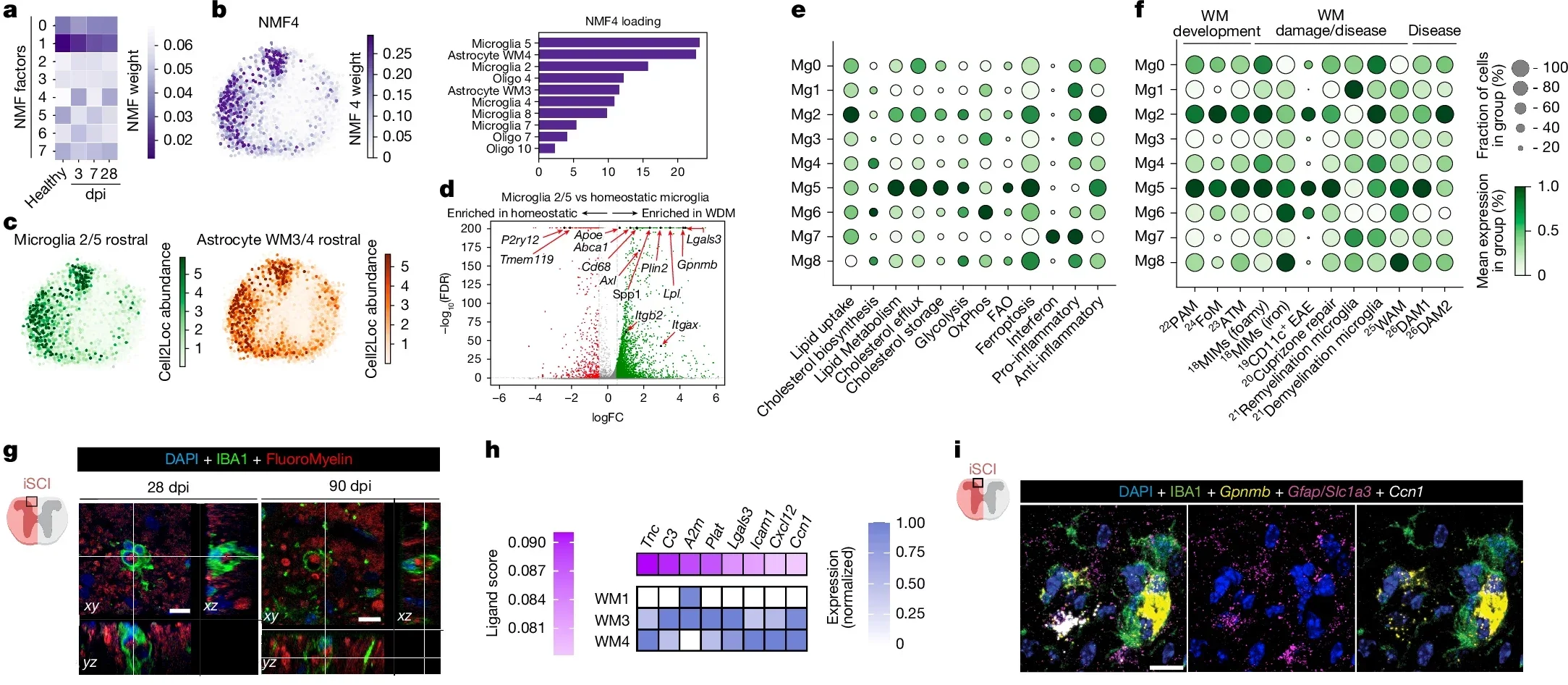

To understand how LRAs help, the Burda Lab looked closely at one LRA subtype. Those astrocytes release a protein called CCN1. That protein works as a signal to microglia, the brain and spinal cord’s resident immune cells.

“One function of microglia is to serve as chief garbage collectors in the central nervous system,” Burda said. “After tissue damage, they eat up pieces of nerve fiber debris, which are very fatty and can cause them to get a kind of indigestion.”

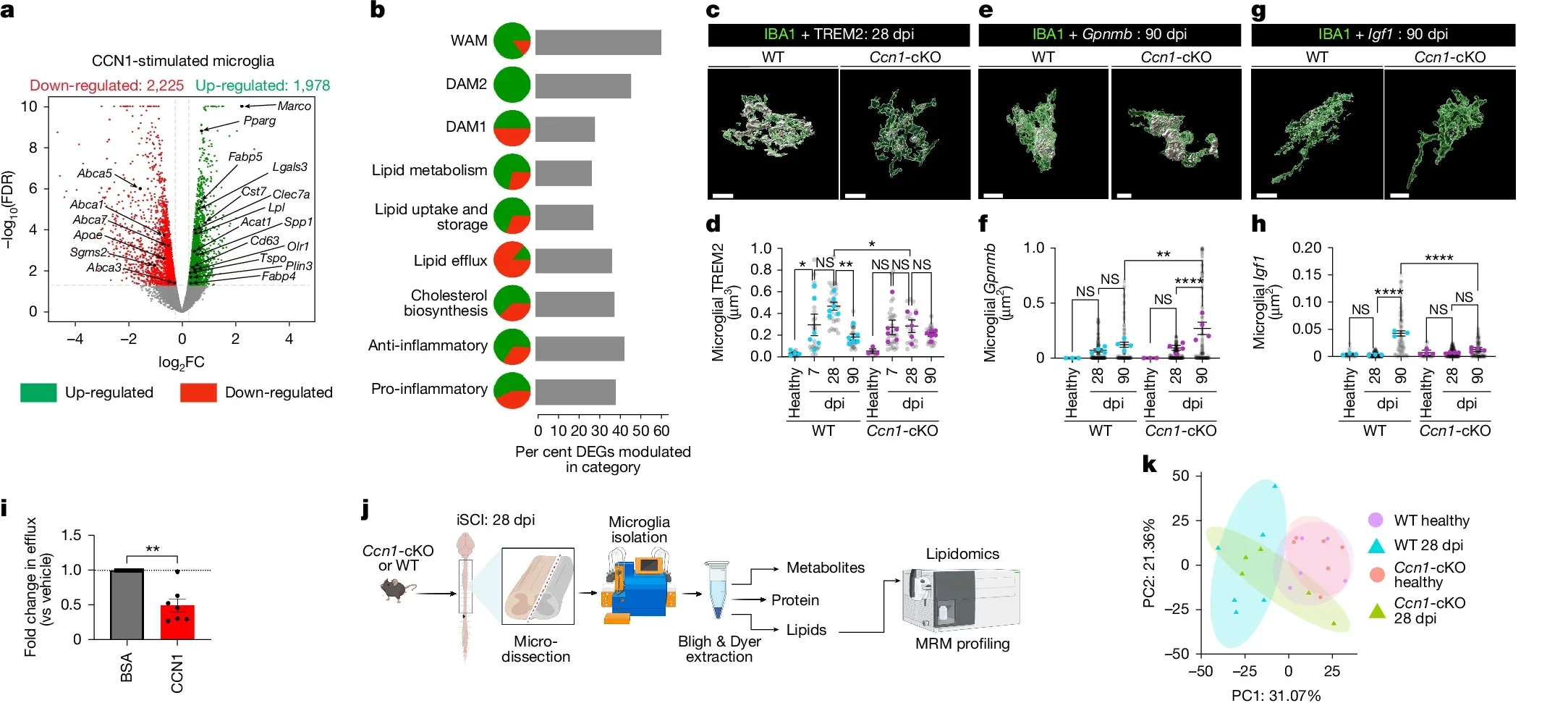

In other words, microglia can choke on the same debris they need to clear. The team’s experiments showed that CCN1 helps prevent that. Astrocyte CCN1 tells microglia to change how they handle energy and fats. With that shift in metabolism, microglia digest the debris more effectively instead of being overwhelmed.

Burda believes this efficient cleanup may help explain why some people with spinal cord injury show spontaneous recovery of function. Their nervous system’s own support cells may be quietly improving the odds.

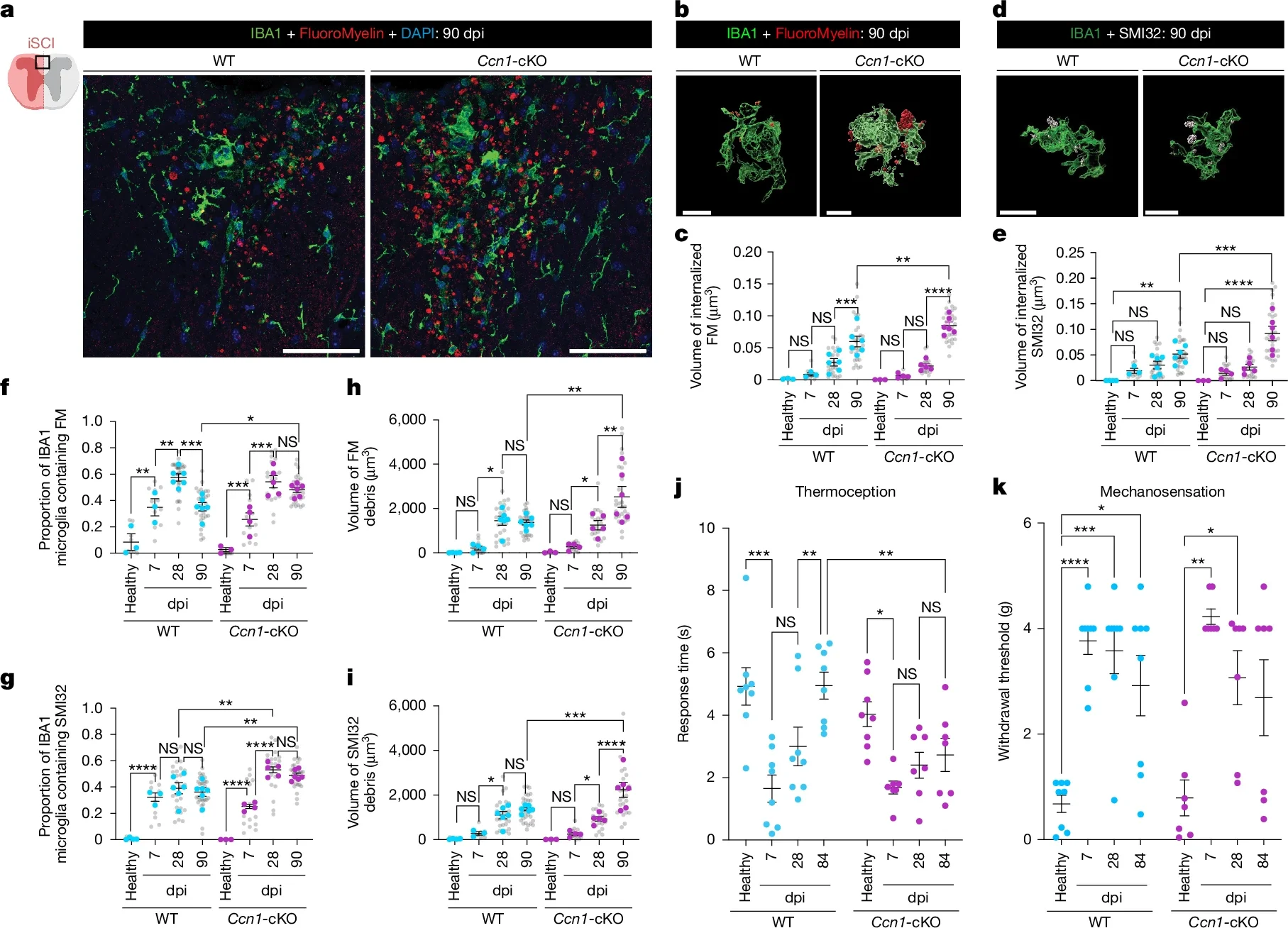

To test how crucial that protein is, the team removed CCN1 from astrocytes in their mouse model. The results were striking. Without astrocyte-derived CCN1, the animals’ recovery dropped sharply.

“If we remove astrocyte CCN1, the microglia eat, but they don’t digest,” Burda said. “They call in more microglia, which also eat but don’t digest.”

Instead of a clean repair site, the spinal cord filled with big clusters of debris-stuffed microglia. Those clusters drove stronger inflammation up and down the cord. With inflammation spread along that axis, the tissue did not repair as well, and function remained impaired.

This chain reaction shows how tightly linked astrocytes and microglia are in the healing process. When astrocytes send the right signals, microglia help. When that signal is missing, the same cleanup crew can make things worse.

The team did not stop with traumatic injury. When they examined spinal cord tissue from people with multiple sclerosis, they saw the same CCN1 mechanism at work.

Multiple sclerosis damages white matter and leaves behind myelin and nerve fiber debris, much like spinal cord injury. Seeing the same astrocyte–microglia program in MS tissue suggests that this repair pathway is a general feature of central nervous system damage, not a rare response.

Burda said these principles of tissue repair likely apply across many injuries of the brain and spinal cord, including stroke and inflammatory neurodegenerative disease.

“The role of astrocytes in central nervous system healing is remarkably understudied,” said David Underhill, PhD, chair of the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai. “This work strongly suggests that lesion-remote astrocytes offer a viable path for limiting chronic inflammation, enhancing functionally meaningful regeneration, and promoting neurological recovery after brain and spinal cord injury and in disease.”

Right now, CCN1 is simply part of your body’s own toolkit. The Cedars-Sinai group wants to turn that natural signal into a treatment.

Burda is leading efforts to find ways to boost or mimic astrocyte CCN1 after spinal cord injury. If doctors could enhance this pathway, they might help microglia clear debris faster, shorten the period of damaging inflammation and support better recovery.

The team also plans to study how astrocyte CCN1 shapes inflammatory neurodegenerative diseases and aging. As people live longer, conditions that damage white matter and disrupt brain signaling become more common. A deeper understanding of this repair system could shift how those illnesses are treated.

The study shows that cells far from an obvious injury still matter. Their quiet, long distance work can tilt the balance between persistent inflammation and meaningful healing. For people living with spinal cord injury, stroke or multiple sclerosis, that insight offers a new source of hope.

This research shows that your nervous system has a built in repair program that depends on communication between astrocytes and microglia. By identifying CCN1 as a key signal, the study points to drug targets that could enhance cleanup of myelin and nerve debris after spinal cord injury, stroke or multiple sclerosis.

If scientists learn how to boost CCN1 in the right cells at the right time, future treatments may limit chronic inflammation, reduce scarring and support better recovery of movement and sensation. Because the same mechanism appears in human tissue from different diseases, this pathway could eventually help patients with a wide range of brain and spinal cord disorders, including inflammatory neurodegeneration and age related white matter damage.

Beyond therapies, the work also offers a new way to think about prognosis. Biomarkers tied to astrocyte CCN1 activity might help doctors predict which patients are likely to recover more function after injury, and which patients may need more aggressive support. In the long term, harnessing lesion remote astrocytes could shift care from simply stabilizing damage to actively guiding the brain and spinal cord toward repair.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Silent spinal cord cells may hold the key to healing after devastating injuries and brain disease appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.