Astronomers at Durham University and collaborators at the University of Warwick used the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope to spot something that should not exist: a bright bow-shaped shock wave wrapped around a compact dead star system called RXJ0528+2838. The finding suggests this tiny stellar remnant is pushing material into space far more strongly than current models allow.

“We found something never seen before and, more importantly, entirely unexpected,” says Simone Scaringi, an associate professor at Durham University and a co-lead author. “The surprise that a supposedly quiet, discless system could drive such a spectacular nebula was one of those rare ‘wow’ moments,” Scaringi says.

Krystian Ilkiewicz, a postdoctoral researcher at the Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center in Warsaw and a co-lead author, says the observations point to a major gap in understanding. “Our observations reveal a powerful outflow that, according to our current understanding, shouldn’t be there,” he says. Astronomers use “outflow” to describe matter ejected from an object into space.

RXJ0528+2838 sits about 730 light-years away. It is a tight binary that completes an orbit every 80 minutes, near the theoretical minimum for this kind of system. The main object is a white dwarf, the leftover core of a low-mass star. A Sun-like companion orbits nearby, and the white dwarf pulls gas from it.

“RXJ0528+2838 belongs to a class called “polars,” a type of cataclysmic variable. In polars, a white dwarf’s magnetic field is so strong that it guides incoming gas onto the star’s surface. That same magnetism usually prevents a broad accretion disk from forming,” Scaringi explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“That detail matters. In many other white-dwarf binaries, the leading explanation for large nebulae and shock structures involves winds driven off an accretion disk. Here, astronomers see no evidence of a disk. Yet they see a large nebula shaped like a bow shock,” he continued.

Noel Castro Segura, a research fellow at the University of Warwick and a collaborator on the work, describes a bow shock as “a curved arc of material, similar to the wave that builds up in front of a ship.” In this case, the arc appears as the system plows through interstellar gas. The shock lines up with the system’s motion through space, tying the structure to RXJ0528+2838 rather than an unrelated cloud.

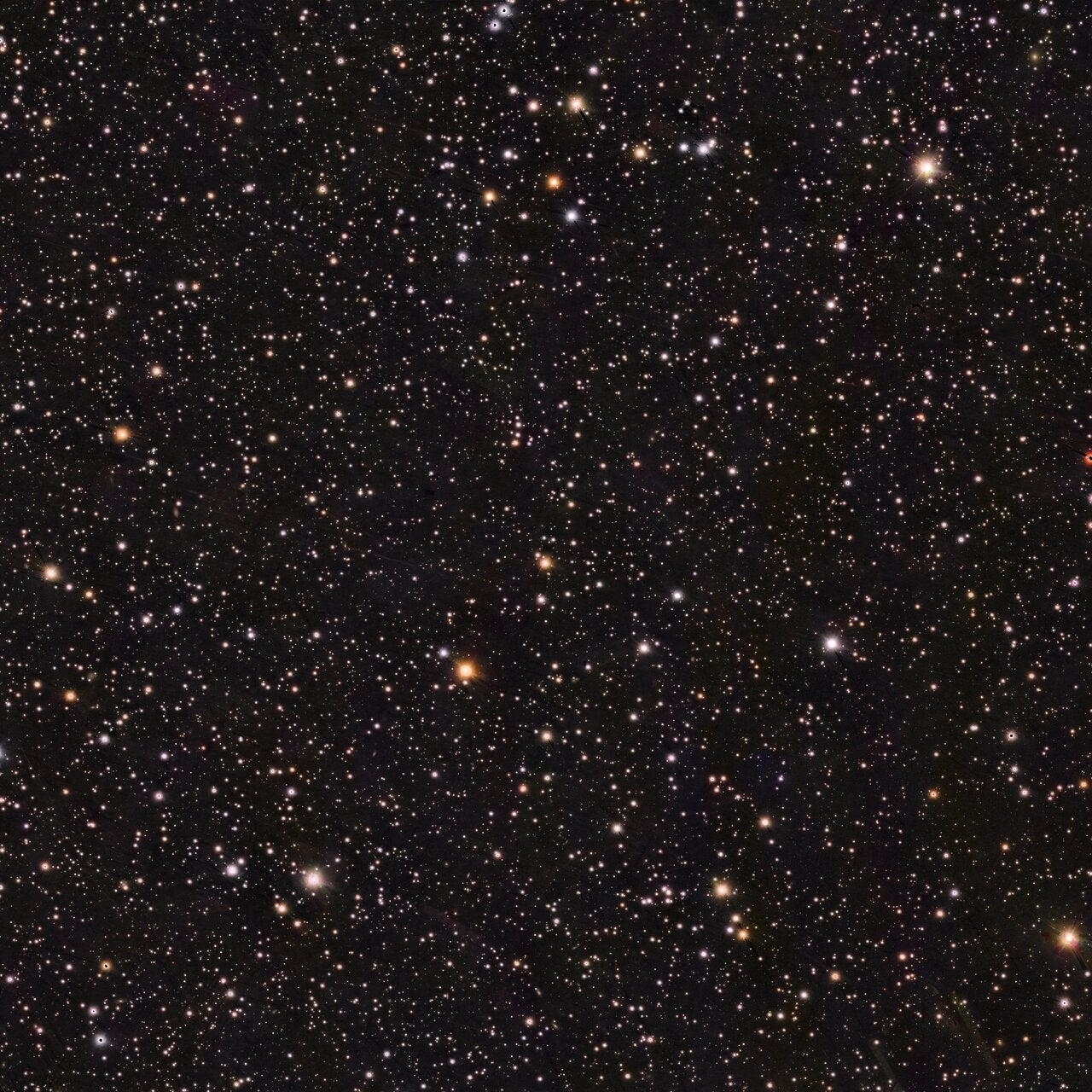

The team first noticed the nebulosity in images from the Isaac Newton Telescope in Spain. They then used the MUSE instrument on ESO’s Very Large Telescope to map the nebula in detail. “Observations with the ESO MUSE instrument allowed us to map the bow shock in detail and analyze its composition. This was crucial to confirm that the structure really originates from the binary system and not from an unrelated nebula or interstellar cloud,” Ilkiewicz says.

The bow shock changes depending on which chemical emission line astronomers use to view it. In hydrogen lines, the tip of the shock sits farthest from the system. In nitrogen and oxygen emission, the apex appears closer in. Sulfur emission looks different again, showing a more diffuse glow between the star and the hydrogen-defined apex.

Brightness also tilts to one side. Although the system’s motion points nearly southeast, the nebula appears brighter to the southwest across multiple emission lines. That pattern suggests the outflow is not symmetrical. In particular, the oxygen emission may trace a more directed flow.

MUSE also reveals a trailing structure, a tail behind the system. The visible portion stretches beyond the instrument’s field of view, and the system’s known motion implies the tail has persisted for at least about 1,000 years. The bow shock’s size and shape point the same way: the system appears to have been driving a strong outflow for roughly a millennium.

Researchers tested the usual ideas and found each one comes up short.

A disk wind does not work because RXJ0528+2838 lacks a disk. A pulsar-like engine does not fit because the compact object is a white dwarf, not a neutron star. The team also checked for radio emission that might hint at a pulsar and saw no radio source at the system’s position, making that scenario unlikely unless the emission is narrowly beamed away from view.

A classical nova shell also looks wrong. A nearby nova would likely have been noticed, and nova shells usually expand outward in a more rounded form. This nebula instead shows a sharp bow shape aligned with motion, plus a smooth trailing tail. The velocity patterns also do not match a rapidly expanding shell.

Then there is the energy problem. Based on the bow shock’s size, the system’s speed through space, and estimates of local interstellar density, the study calculates that sustaining the bow shock requires about 8.2 × 10^32 erg per second. That is a huge power demand for a system like this.

A typical donor-star wind would need an absurd velocity to supply that energy. The white dwarf’s rotational spin-down cannot provide enough power either, based on limits from timing data. Orbital energy from the binary’s slow inspiral might look tempting on paper, but astronomers do not have a working mechanism that turns that energy into a sustained outflow of this sort.

Even magnetism struggles to close the gap. The white dwarf’s magnetic field is strong, measured around 42 to 45 megagauss, and it likely channels accreted gas directly onto the surface. “Our finding shows that even without a disc, these systems can drive powerful outflows, revealing a mechanism we do not yet understand. This discovery challenges the standard picture of how matter moves and interacts in these extreme binary systems,” Ilkiewicz says.

![The red, green and blue channels correspond to the Hα, [N ii] 6,548 Å and [O iii] 5,007 Å lines, respectively, extracted using a top-hat filter from the MUSE data cube. The grey arrow indicates the proper motion of RXJ0528+2838. North is up; east is left. Dec., declination; ICRS, International Celestial Reference System; RA, right ascension.](https://www.thebrighterside.news/uploads/2026/01/shock-wave-5.webp)

But the study also notes a mismatch between the observed thousand-year structure and how long the measured magnetic field could power such a shock under straightforward assumptions. That leaves what Scaringi calls a hidden “mystery engine.”

One possibility is that RXJ0528+2838 is in a rare phase, perhaps linked to changes in magnetic configuration or past episodes of different rotational behavior. Another is that astronomers are seeing an energy-loss channel that has been missed in similar systems, possibly one that becomes more important during low accretion states.

The team argues that solving the puzzle will require finding more examples. ESO’s upcoming Extremely Large Telescope could help by mapping fainter systems and surveying a broader population. Scaringi expects it to help astronomers “to map more of these systems as well as fainter ones and detect similar systems in detail, ultimately helping in understanding the mysterious energy source that remains unexplained.”

This discovery matters because it hints that some close white dwarf binaries may inject far more energy into surrounding space than scientists assumed. If that is true, it could change how researchers model how these systems evolve over time, including how they lose energy and mass. It also raises the chance that similar binaries quietly reshape their local interstellar neighborhoods, stirring gas and creating shock-heated regions that affect future star formation on small scales.

For astronomy research, the work creates a clear target: identify the missing power source and test whether it appears only in rare conditions. That could push new theory on magnetic interactions, accretion flows without disks, and how compact binaries exchange energy with their environment.

In a broader sense, it improves the physical picture used across astrophysics whenever strong magnetic fields and flowing plasma collide.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers spot an ‘impossible’ shock wave around a dead star system appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.