Researchers at the Institute of Science Tokyo in Japan, also known as Science Tokyo, have taken a fresh look at a long running question in aging and brain science. Can the health of your teeth and mouth shape the risk of dementia later in life?

The work is led by Professor Jun Aida of the Department of Dental Public Health at Science Tokyo’s Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences. Aida and his team reviewed dozens of large population studies and also ran their own long term research. Their goal was to sort out whether poor oral health truly raises dementia risk or whether the link is more complicated.

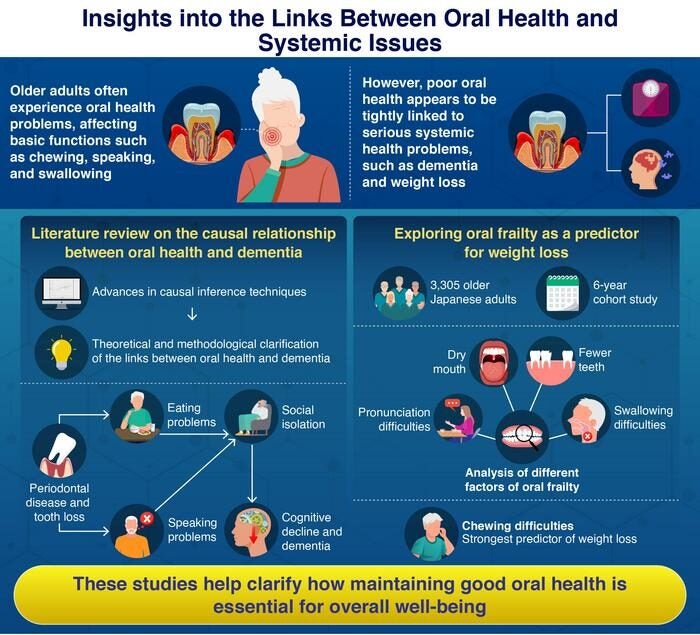

Their main review appeared in the Journal of Dental Research. It brought together new methods from epidemiology that try to move beyond simple correlation. Aida’s group also published a six year study in the same journal on Aug. 16, 2025, focused on oral frailty and weight loss in more than 3,000 older Japanese adults.

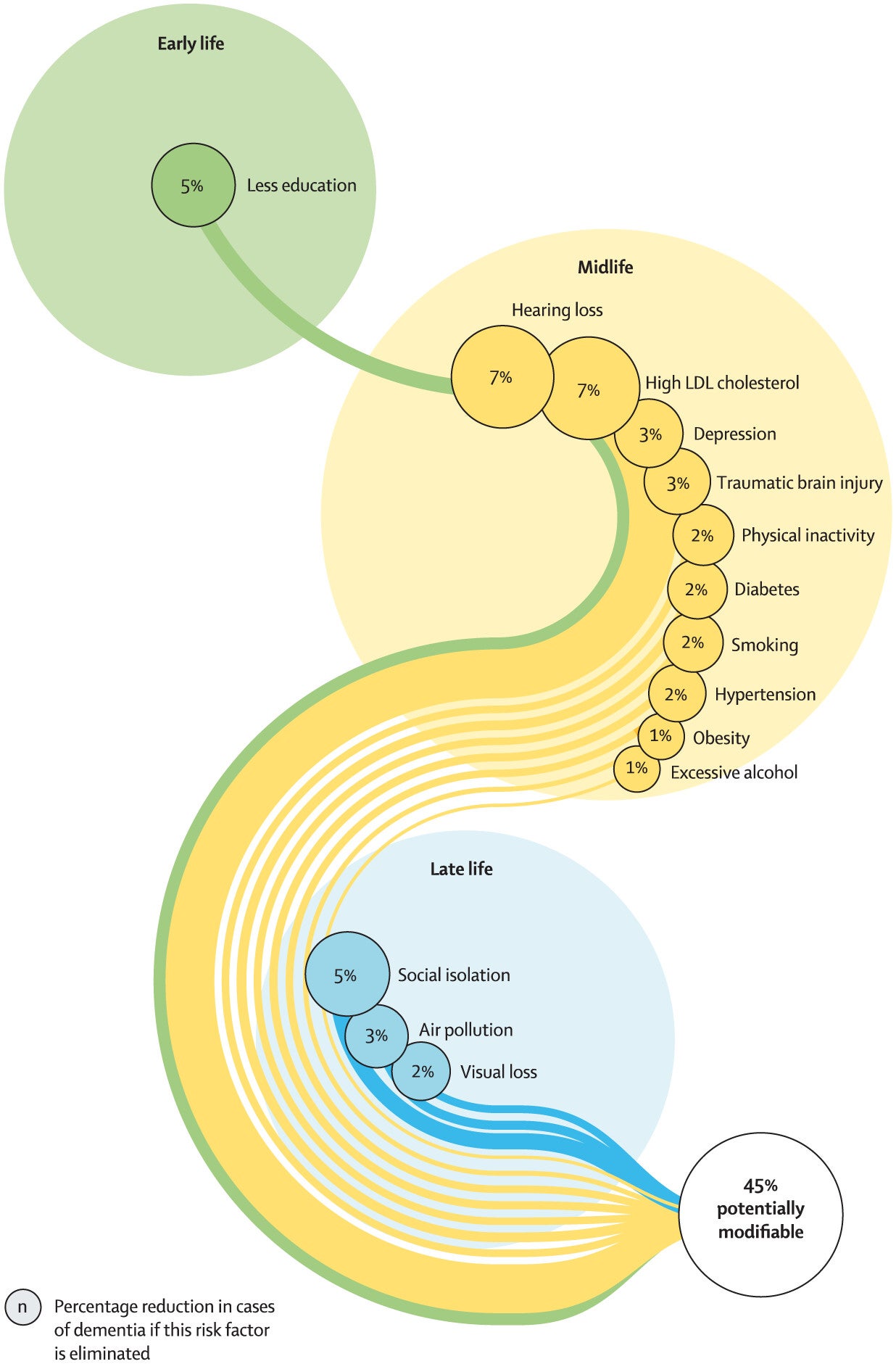

Dementia is already one of the world’s biggest health challenges. About 57.4 million people lived with the condition in 2019. That number is expected to reach 152.8 million by 2050. Memory, language, and behavior problems slowly erode daily life. Alzheimer disease is the most common type.

For years, many studies have reported that people with tooth loss or gum disease tend to show worse thinking and memory. But whether one causes the other has remained unclear. Aida’s team set out to explain why the link is so hard to prove and why social life might matter more than once thought.

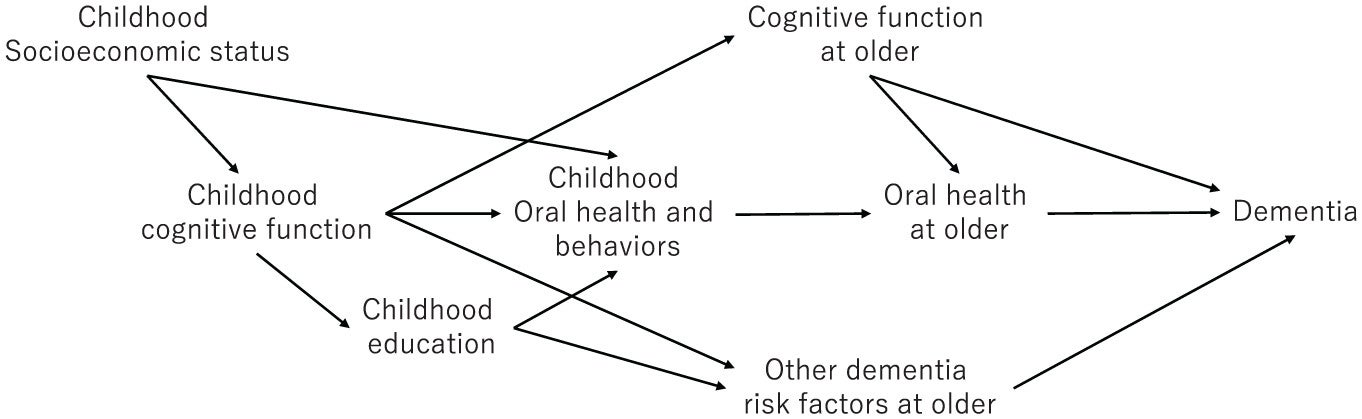

“One major problem is reverse causality. Cognitive decline often makes daily habits harder. People with memory problems may forget to brush, miss dental visits, or struggle with oral care. That can lead to tooth loss and infection. In that case, poor oral health is a result of brain decline rather than a cause,” Aida explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“Another challenge comes from factors that start early in life. Childhood cognitive function is one example. Children with lower cognitive scores are more likely to develop poor dental habits as adults. They also face a higher risk of cognitive problems in old age. That makes it hard to know if teeth problems later in life are driving dementia or just marking who was already on a risky path,” he continued.

Aida’s review explains that many older studies did not measure childhood thinking skills at all. That means hidden confounding can bias results even when modern statistics are used.

Some researchers now apply tools such as repeated surveys and advanced causal models. These track people over time and try to see what changes first, teeth or memory. A large English study found that the relationship runs both ways, but it suggested oral health had a stronger effect on later thinking than the reverse.

More complex approaches, known as g methods, also point in that direction. These models attempt to handle feedback between changing health and changing cognition. They have linked natural teeth, chewing difficulty, dry mouth, and tooth loss with later cognitive problems in the United States, Japan, and Singapore.

Still, even these designs cannot reach back into childhood. That leaves room for doubt about how much of the link is truly causal.

Because long term trials are not practical, some teams use natural experiments. These include fixed effects analysis and instrumental variables. One English study used childhood exposure to water fluoridation as a stand in for lifelong dental health. Each extra year of fluoridated water between ages 5 and 20 was linked to 0.73 more teeth in old age. One extra tooth was tied to a 3 percentage point drop in the chance of daily living limits, which reflect physical and cognitive function.

Other studies, however, found no clear link between tooth loss and dementia when using similar tools. Genetic approaches called mendelian randomization also showed little or no connection for gum disease or cavities. Yet a broad review of trials and cohort studies suggested that dental care and oral exercises may help thinking skills.

Aida’s team argues that these mixed results may come from differences in how long people are followed and what parts of oral health are measured.

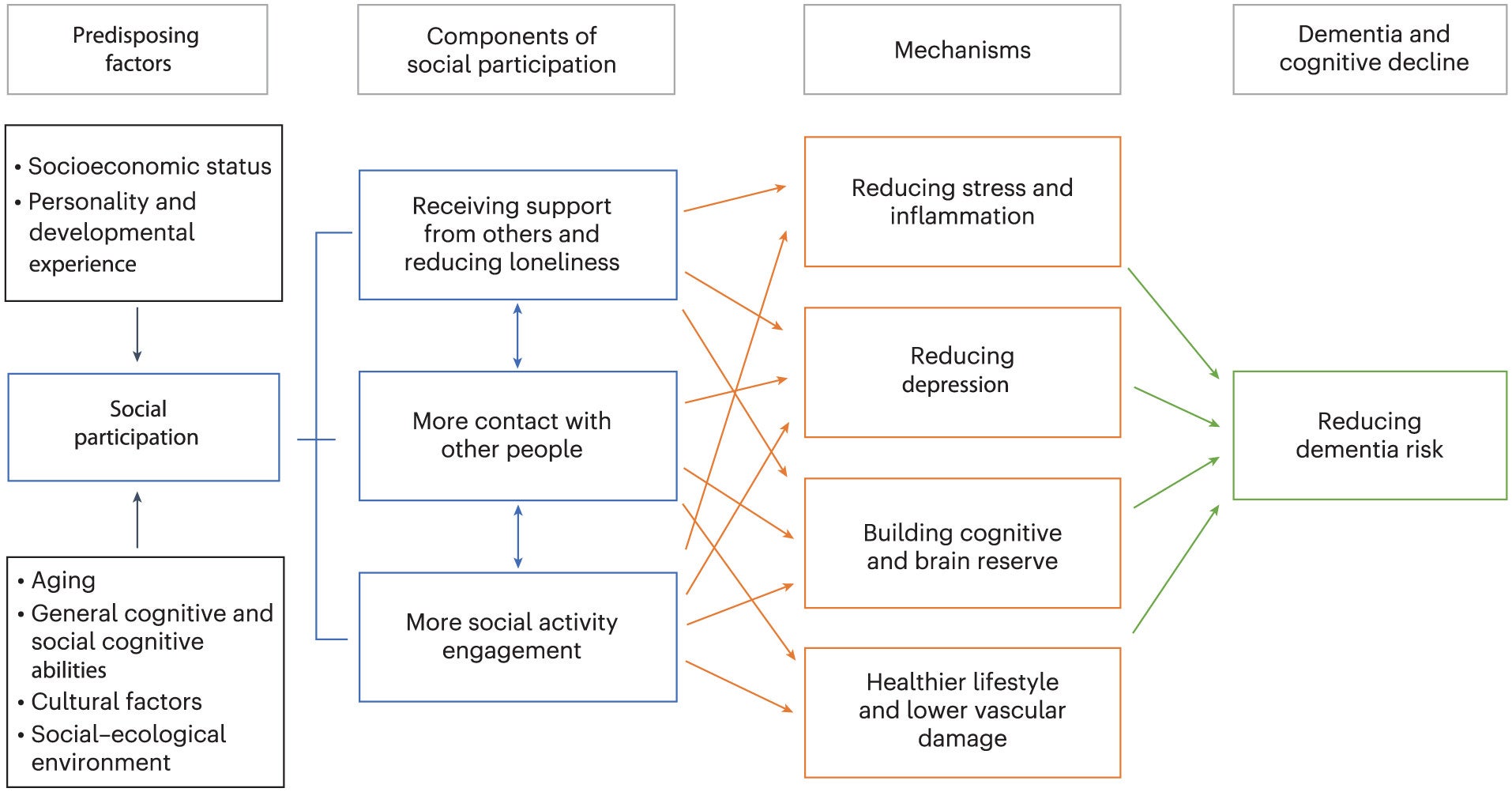

The most novel part of the Science Tokyo review is its focus on daily life. Teeth and jaws do not only grind food. They help you speak, smile, and share meals. These are core parts of human contact.

“These functions have a social aspect that facilitates interpersonal interactions and can reduce social isolation,” Aida said. “When we consider the multilayered direct and indirect mechanisms leading to dementia throughout life, we find that poor oral health possibly increases the risk of dementia through social isolation via eating and speaking problems.”

Social isolation is now seen as a modifiable risk factor for dementia. Studies show that people with worse oral health are more likely to feel lonely, stay home, and avoid social events. Eating alone, which is more common among those with few teeth and no dentures, is linked to weight loss. Weight loss can lead to frailty, and frailty raises dementia risk.

Nutrition also plays a role. Poor chewing makes it harder to eat protein rich foods. Lower protein intake has been tied to higher dementia risk. One study using mediation analysis found that having fewer teeth raised dementia risk partly through diet and social contact.

Aida’s own six year study strengthens this picture. His team followed more than 3,000 older adults in Japan. They tracked oral frailty, which includes dry mouth, missing teeth, and chewing problems. Chewing difficulty turned out to be the strongest predictor of weight loss.

Weight loss in later life often signals poor nutrition and declining health. That can weaken the brain and body. The finding supports the idea that oral function sits at the center of a web linking diet, social life, and cognition.

“Together, our papers provide important evidence that oral health affects not only the teeth and mouth, but also broader aspects of health, including brain function, nutritional status, and social engagement,” Aida said.

Oral disease is extremely common worldwide. Even if its effect on dementia is modest, the sheer number of people affected could make it important at the population level. One Japanese study found that poor oral health had a larger impact on mortality than smoking in some groups.

That does not prove it causes dementia. But it suggests that improving oral health could bring wide benefits, especially when it supports eating and social ties.

The Science Tokyo work suggests that caring for teeth and oral function may do more than protect smiles. By helping people chew, speak, and eat with others, good oral care could support nutrition and social connection.

Both are known to protect brain health. For researchers, the findings push the field to look beyond inflammation and bacteria and include daily function and social life.

For older adults and caregivers, the work highlights that dental care, dentures, and oral exercises may help preserve quality of life and possibly slow pathways that lead toward cognitive decline.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Dental Research.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Oral health and dementia have a surprisingly complex relationship, study finds appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.