Radio telescopes let you study the universe by collecting faint radio waves from distant objects. To see extremely small targets, such as the regions around supermassive black holes, those telescopes must work together. They have to observe the same object at the same moment and stay perfectly synchronized. That challenge sits at the heart of a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry, or VLBI.

Researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, known as KAIST, now report a major advance that improves how this synchronization is done. The team is led by Professor Jungwon Kim of KAIST’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. The work was carried out with collaborators from the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science, and the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Germany. Their findings were in the journal Light Science & Applications.

The group developed a new way to deliver ultra-precise timing signals directly into radio telescope receivers using light. The method relies on optical frequency comb lasers, a technology often described as an ultra-precise ruler made of light. Instead of improving existing electronics step by step, the team replaced key electronic references with a photonic system built around lasers.

VLBI works by linking radio antennas spread across large distances. Each telescope records signals from the same cosmic source, guided by a local atomic clock. When those signals are later combined, the array behaves like a single telescope the size of Earth. This approach can reach angular resolution measured in tens of micro-arcseconds, sharp enough to study black hole shadows.

That precision depends on measuring extremely small differences in timing and phase. Many factors interfere with that process. The atmosphere adds noise, especially water vapor in the troposphere. Electronics inside each telescope can drift. Reference clocks are not perfectly stable. As observing frequencies increase, those problems become harder to manage.

To reduce atmospheric effects, astronomers often observe at several frequencies at once. Lower-frequency data can help correct errors at higher frequencies. This multi-frequency approach is central to black hole studies, relativistic jets, stellar evolution research, and millimeter-wavelength geodesy. Still, even with multiple frequencies, performance is limited by how well each telescope calibrates its own signal chain.

Most VLBI systems inject a phase calibration signal, known as PCAL, into each receiver band. This signal appears as a series of evenly spaced tones across the observing band. By tracking those tones, scientists can measure and correct phase drift caused by the instrument itself.

Electronic methods for generating PCAL signals face growing limits. Their usable frequency range often stops near 50 gigahertz. Tone strength can vary across the band, forcing trade-offs between weak signals at high frequency and overly strong ones at low frequency. As receivers expand to cover broader bandwidths, those issues become more severe. In sub-millimeter VLBI, instrumental phase calibration is now considered a major bottleneck.

Local oscillators add another complication. These microwave signals convert incoming radio waves to lower frequencies that electronics can process. They must be extremely stable and usually trace back to a hydrogen maser clock. Creating clean, low-noise microwave signals at high frequencies from a low-frequency reference often requires complex multiplication chains that degrade signal quality.

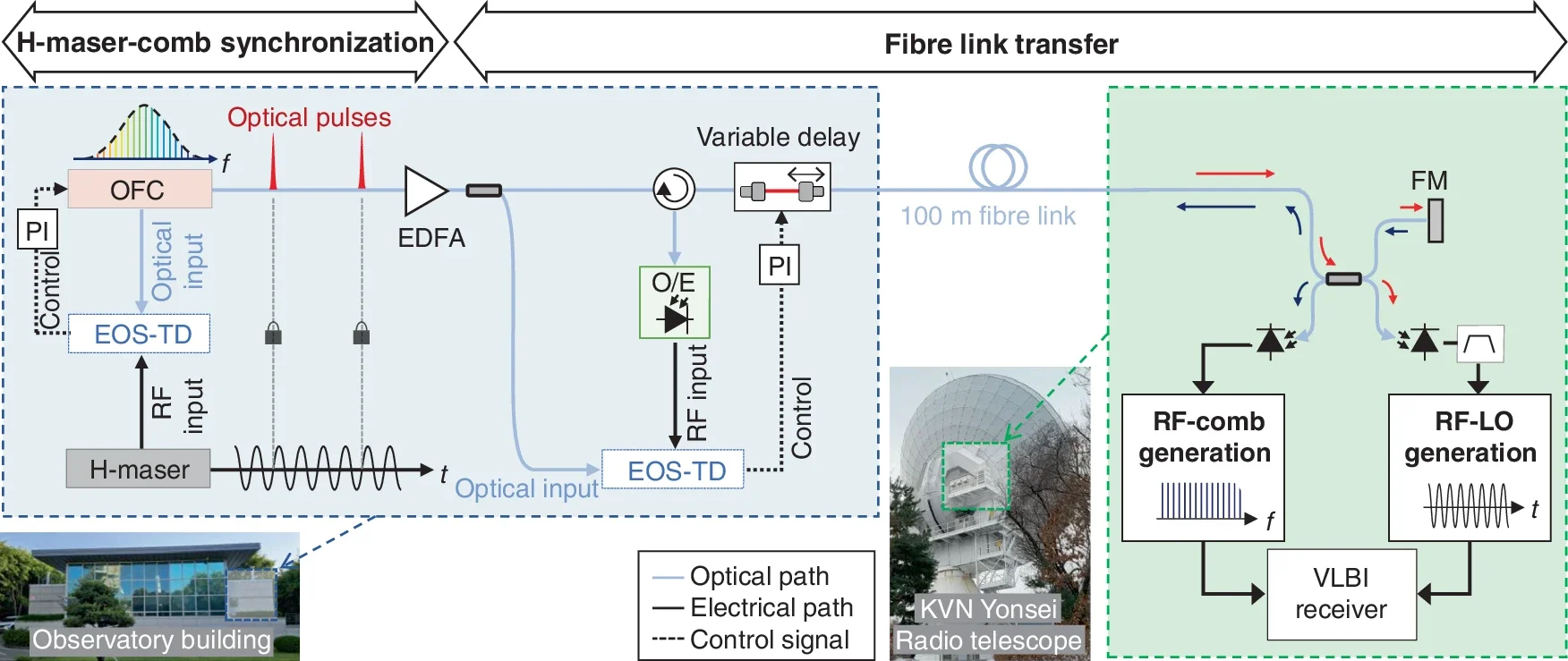

“Our research team addressed both calibration and oscillator challenges with a single photonic approach. Optical frequency combs produce tens of thousands of evenly spaced optical frequencies, all locked to an atomic reference. When detected with fast photodiodes, those optical pulses naturally form a broadband radio-frequency comb,” Kim shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“In this system, the same comb provides a wideband PCAL signal and multiple low-noise local oscillator tones. By filtering specific harmonics, we extracted stable microwave frequencies suitable for telescope receivers,” he continued.

The demonstration took place at the Korean VLBI Network Yonsei Radio Telescope in Seoul. A mode-locked erbium fiber laser with a 40 megahertz repetition rate was synchronized to a hydrogen maser housed at the observatory. The optical pulses were sent through a 100-meter stabilized fiber link to the antenna receiver room.

To keep timing errors extremely low, the team stabilized both the laser and the fiber link using electro-optic sampling timing detectors. These devices measure timing differences with sub-femtosecond resolution. Over long runs exceeding 30,000 seconds, the system maintained coherence well beyond typical VLBI observing scans.

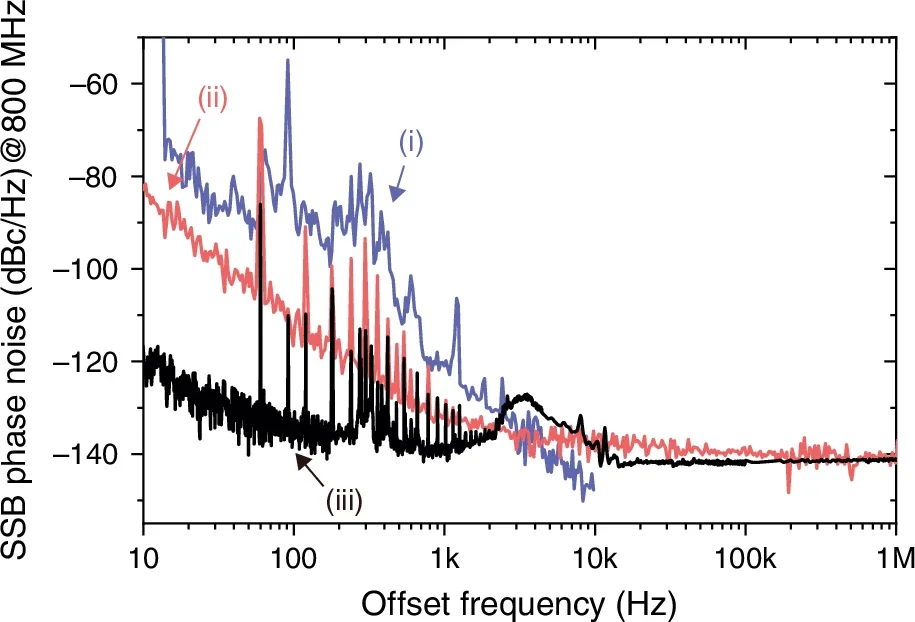

The researchers converted the optical pulses into a radio-frequency comb extending to 50 gigahertz, limited only by the measurement equipment. The comb showed nearly uniform amplitude across the band. The same signal was used to generate local oscillator tones at 16.64 and 19.2 gigahertz, with very low phase noise.

A real VLBI test followed in May 2024. All four Korean VLBI Network telescopes took part, observing 40 known cosmic radio sources at 22 and 43 gigahertz. Data were recorded at 8 gigabits per second and processed with standard VLBI software.

The results showed stable interference fringes across the array. Detection rates reached about 92 percent. Phase calibration tones remained steady in both amplitude and phase during observations. Measurements confirmed that instrumental delay errors were well controlled, demonstrating that the photonic system worked under real observing conditions.

Professor Jungwon Kim said, “This research is a case where the limits of existing electronic signal generation technology were overcome by directly applying optical frequency comb lasers to radio telescopes. It will significantly contribute to improving the precision of next-generation black hole observations and advancing the fields of frequency metrology and time standards.”

Dr. Minji Hyun, now at KRISS, and Dr. Changmin Ahn of KAIST served as co-first authors on the study.

This work points toward clearer and more reliable images of black holes by reducing one of VLBI’s most stubborn sources of error. By improving phase calibration and local oscillator stability at the same time, the method helps radio telescopes behave more like a single, perfectly synchronized instrument.

Beyond astronomy, the approach could support intercontinental clock comparisons, space geodesy, and deep-space probe tracking. Optical frequency combs form a natural bridge between optical clocks and microwave systems.

In the future, this could allow next-generation optical clock precision to reach radio observatories directly, improving timekeeping and navigation technologies that rely on extreme accuracy.

Research findings are available online in the journal Light Science & Applications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Laser Breakthrough Sharpens Radio Telescope Views of Black Holes appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.