Northern California’s coast keeps you on alert, even on quiet days. Offshore, three tectonic plates meet near Humboldt County at the Mendocino Triple Junction. It is where the San Andreas fault system approaches the Cascadia subduction zone. Scientists have long known the junction is dangerous. Now, a new study says you have been looking at the wrong boundaries.

Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of California, Davis and the University of Colorado Boulder report a new 3D model of the region. The team includes USGS seismologist David Shelly, UC Davis earth and planetary sciences professor Amanda Thomas, CU Boulder researcher Kathryn Materna, and USGS scientist Robert Skoumal. Their work appears in Science.

“If we don’t understand the underlying tectonic processes, it’s hard to predict the seismic hazard,” said co-author Amanda Thomas, professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Davis.

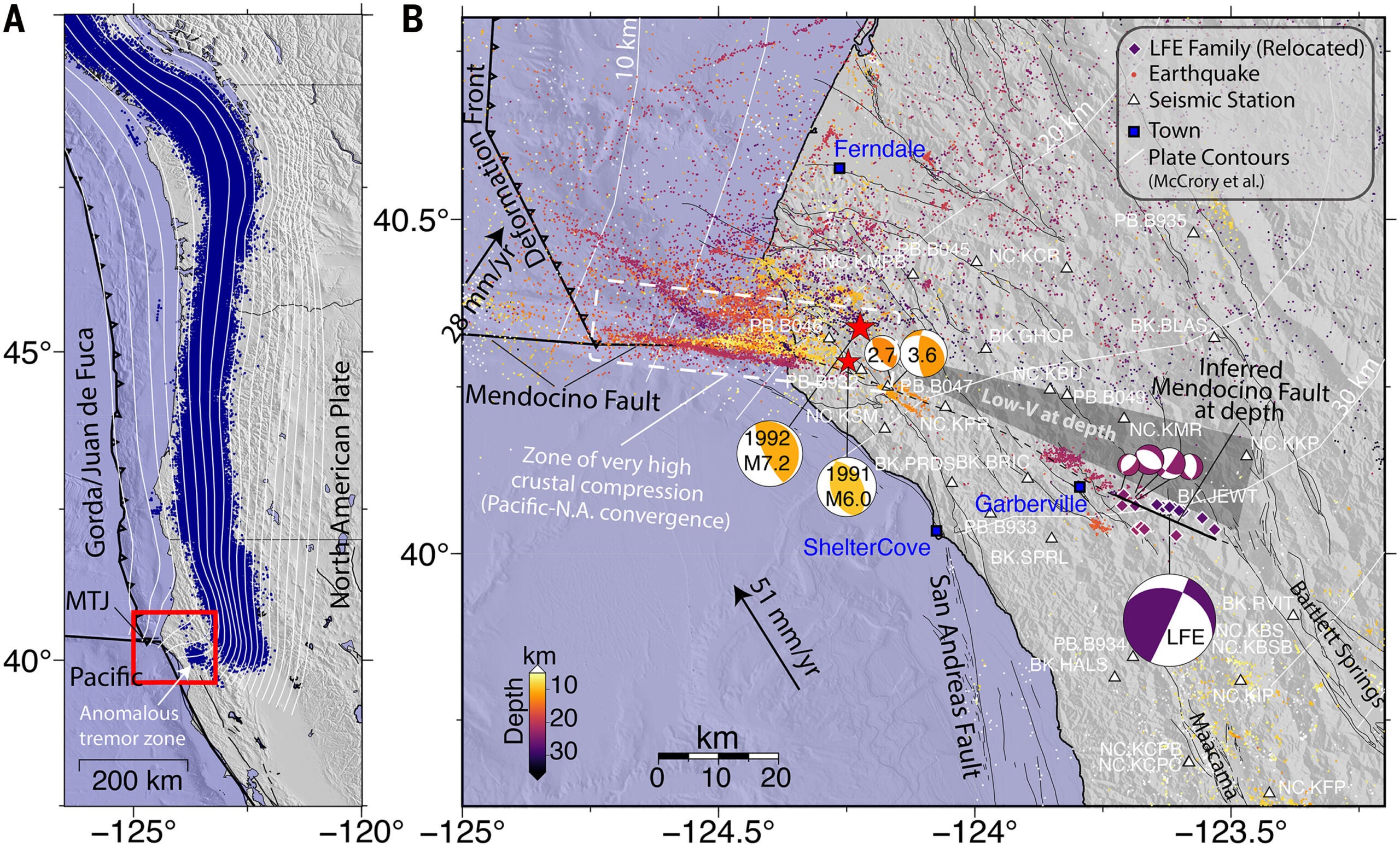

On maps, the triple junction can look simple. South of it, the Pacific plate slides northwest past the North American plate along the San Andreas. North of it, the Gorda plate, part of the Juan de Fuca system, dives under North America in the Cascadia subduction zone. In reality, the junction behaves less like a point and more like a wide, broken zone.

A key puzzle has bothered researchers for decades. In 1992, a magnitude 7.2 Cape Mendocino earthquake struck at a shallower depth than many models expected. That mismatch signaled that something underground did not match the clean lines drawn at the surface.

First author David Shelly of the USGS Geologic Hazards Center in Golden, Colo., compared it to studying an iceberg. “You can see a bit at the surface, but you have to figure out what the configuration is underneath.”

To see deeper, the team tracked swarms of tiny “low-frequency” earthquakes, also called LFEs. These events are far weaker than anything you can feel. They repeat often and can merge into a longer, faint rumble called tremor. Because LFEs recur with similar waveforms, researchers can group them into “families” and locate them more precisely than tremor alone.

Earlier work had flagged an unusual tremor zone west of Cascadia’s main tremor band. It sits about 50 to 100 kilometers farther west than expected. Inside that zone, scientists had already identified 27 LFE families. They aligned along a slanted structure about 22 to 29 kilometers deep, dipping north-northeast.

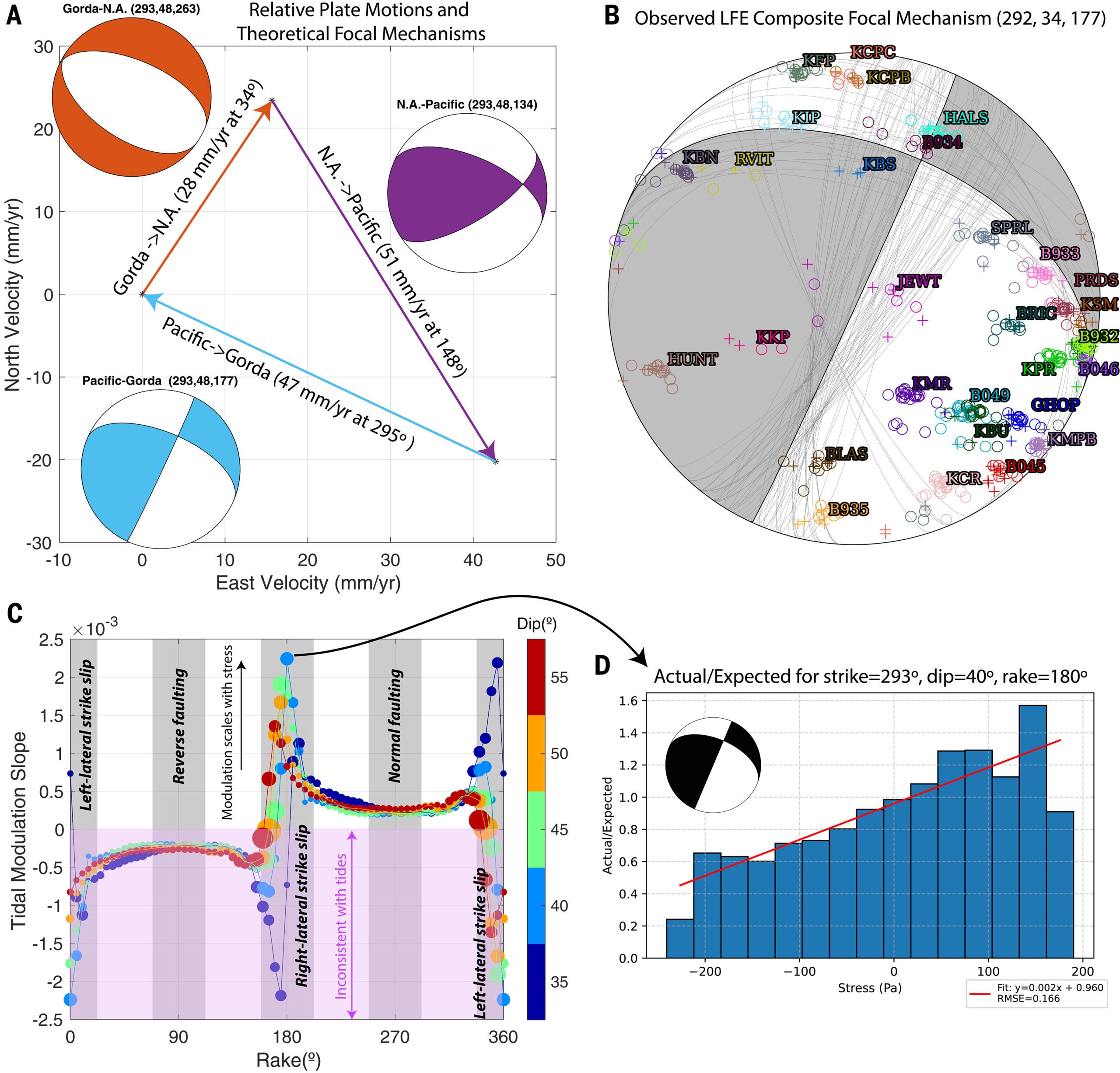

Those LFEs repeat about every two days. That fast pace suggests a fault with a high slip rate. Yet one detail remained missing: the direction of slip. Without it, you could not choose between competing pictures of the triple junction.

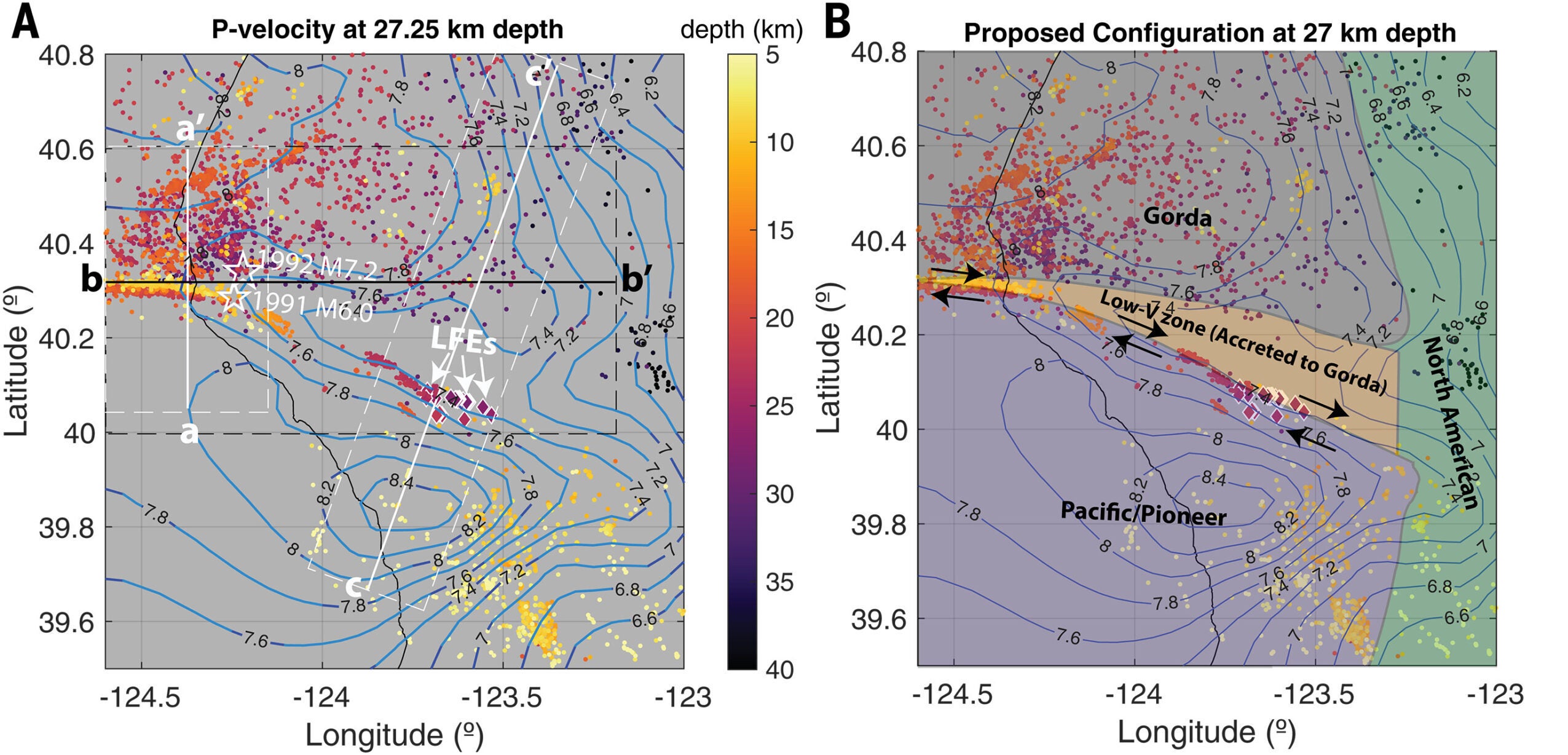

One idea proposed a “slab window,” a gap where the southern edge of the subducting Gorda plate tore away. Another argued for a captured slab fragment, the Pioneer fragment, moving north with the Pacific plate beneath North America. If the Pioneer fragment exists where predicted, it could block a slab window.

“This new study used two independent tests to pin down the motion. First, our team built a composite focal mechanism, based on P-wave first motions. Because LFEs are tiny and noisy, we compared LFE arrivals to nearby earthquakes with known polarity. Those reference quakes came from a persistent cluster near 22 kilometers depth, sometimes called the Garberville swarm,” Shelly told The Brighter Side of News.

The team then tested tidal modulation. Gravity from the sun and moon tugs on Earth’s crust, not just the oceans. If tides push a fault in the direction it already wants to move, LFE activity should rise. Thomas explained that when tidal forces line up with plate motion, you expect more tiny earthquakes.

Both tests pointed to nearly the same answer. The LFE fault shows almost pure strike-slip motion on a plane aligned with the LFE zone. That result fits Pacific-Gorda relative motion better than the slab-window scenario.

With LFE motion constrained, the researchers argue that the triple junction involves five moving pieces, not just the three big plates you see on simplified diagrams. Two of those pieces sit out of sight.

At the southern end of Cascadia, the team concludes that a chunk has broken off the North American plate. It is getting pulled down with the Gorda plate as Gorda sinks beneath North America. South of the triple junction, the Pacific plate appears to drag the Pioneer fragment beneath North America as it moves north.

The Pioneer fragment likely came from the ancient Farallon plate. Much of Farallon has vanished into the mantle over millions of years. The study says this remnant still matters because it creates a hidden boundary that does not show up as a surface fault.

The team says this geometry helps explain the 1992 quake’s shallow depth. Materna described how the study shifts the expected location of major boundaries.

“It had been assumed that faults follow the leading edge of the subducting slab, but this example deviates from that,” Materna said. “The plate boundary seems not to be where we thought it was.”

The study also revisits another major event, the 1991 magnitude 6.0 Honeydew earthquake. Its reverse slip and shallow-dipping nodal planes can fit with interface-related motion in a system where the effective subduction surface sits shallower than the deeper “petrologic” slab.

The paper proposes that the LFE zone marks strike-slip motion between the Pacific system, including the Pioneer fragment, and material linked to the Gorda slab. It also describes a low-velocity corridor south of Gorda slab seismicity. That corridor may include sediment-rich material added to the southern edge of the subducting slab. If so, the functional subduction boundary could sit south of where some slab maps place it.

Fluids may play a role. Accretionary prisms hold water-rich sediments. As that material sinks and heats, fluid pressure can rise. High pressure often links to tremor and LFE activity, and it can allow brittle failure at depths where rock might otherwise deform more smoothly.

The hazard angle is direct. The study suggests a shallow, east-dipping detachment on the surface of the Pioneer fragment. Current fault models may not include it, and the study says it is not considered in the U.S. Geological Survey National Seismic Hazard Model. If that buried structure can rupture, you could face an unrecognized source of strong shaking in a region already crowded with faults.

The team also notes a striking contrast. Near the triple junction, seismicity has been high, including three magnitude 6 or larger earthquakes since 2021. Much of Cascadia has been quieter. That difference raises a possibility that a future Cascadia megathrust event could begin near the triple junction, where systems intersect and strain concentrates.

This work gives you a clearer map of where deep slip may actually occur, not just where surface lines suggest it should. By tying low-frequency earthquakes to strike-slip motion, the study offers a way to test hidden plate-boundary models with real observations. That matters because hazard forecasts depend on where faults sit, how fast they move, and how they connect at depth.

In the long run, the findings can improve earthquake simulations for Northern California and southern Cascadia. If the effective subduction interface sits shallower than expected in places, rupture could occur closer to the surface. That can change shaking estimates and tsunami-related planning in coastal communities.

The method also gives scientists a sensitive tool for tracking subtle changes after large quakes, because tidally influenced LFEs can reveal shifts in deep slip that other measurements might miss.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Tiny earthquakes reveal hidden faults where San Andreas meets Cascadia appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.