Dust and sun define field seasons in East Turkana. So do patience and sharp eyes. In northern Kenya, a set of bones pulled from the ground has now changed what scientists can say about one of your earliest human relatives.

An international research team reports an unusually well-preserved Homo habilis skeleton that dates to just over 2 million years ago. The fossil, labeled KNM-ER 64061, comes from East Turkana and includes the most complete postcranial, meaning below-the-skull, evidence known for this species.

This matters because Homo habilis has long felt like a species known mostly from heads. Scientists have found cranial pieces over decades, but they rarely had enough connected limb and trunk bones to describe how the body looked and worked. With this new skeleton, the conversation shifts from guesswork toward firmer measurements, especially for the shoulders and arms.

The specimen also comes with a crucial bonus, a nearly complete set of mandibular teeth associated with the bones. That dental link lets researchers confidently assign the scattered parts to one individual and to Homo habilis. It also makes this discovery stand out from earlier finds that left more room for doubt.

Homo habilis lived roughly between about 2.5 and 1.4 million years ago. Researchers often describe it as probably ancestral to Homo erectus. Yet many debates about its biology have stayed unresolved, in part because the fossil record for its body has been thin.

“Indeed, there are only three other very fragmentary and incomplete partial skeletons known for this important species,” said Prof. Fred Grine of Stony Brook University, the study’s lead author.

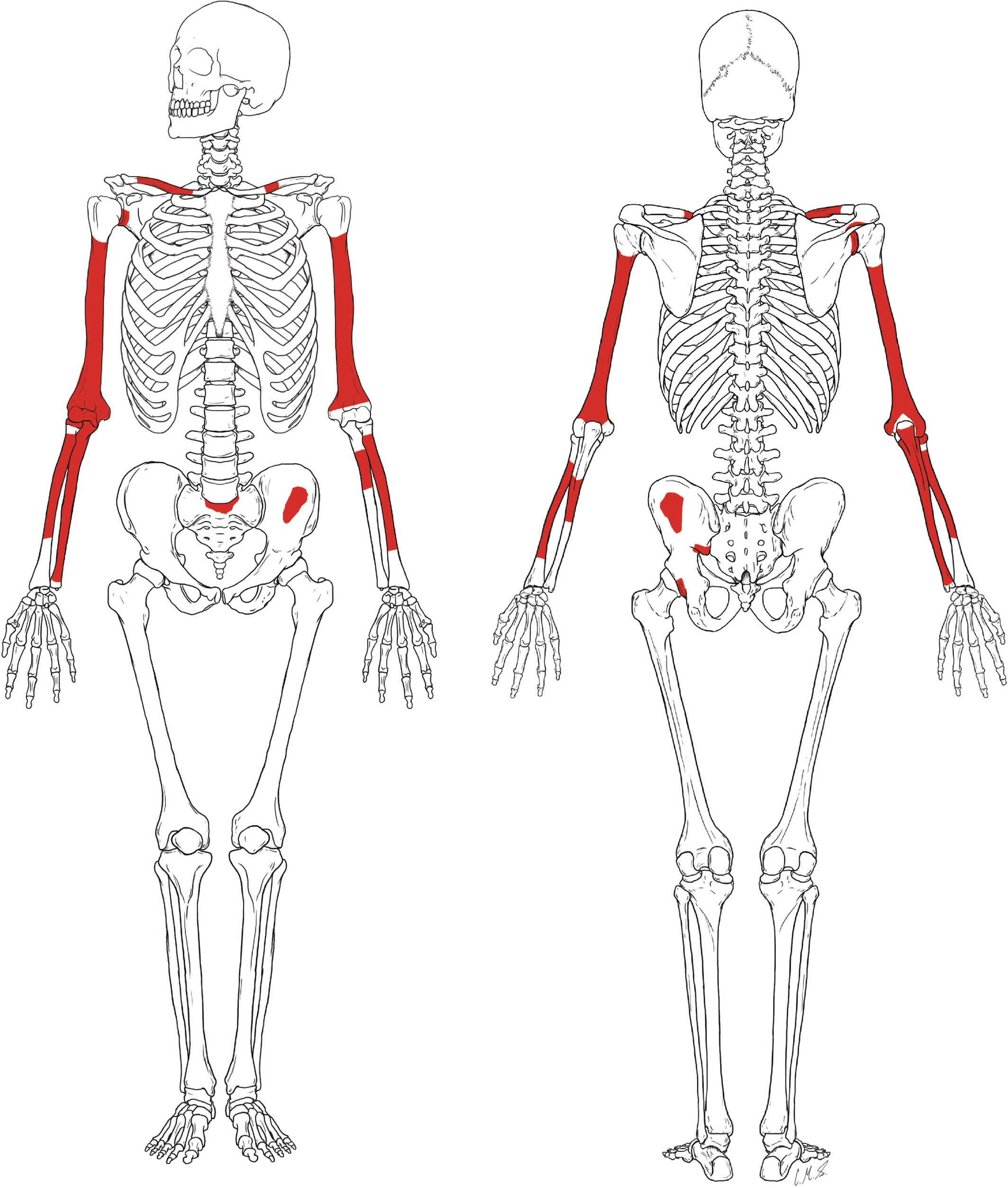

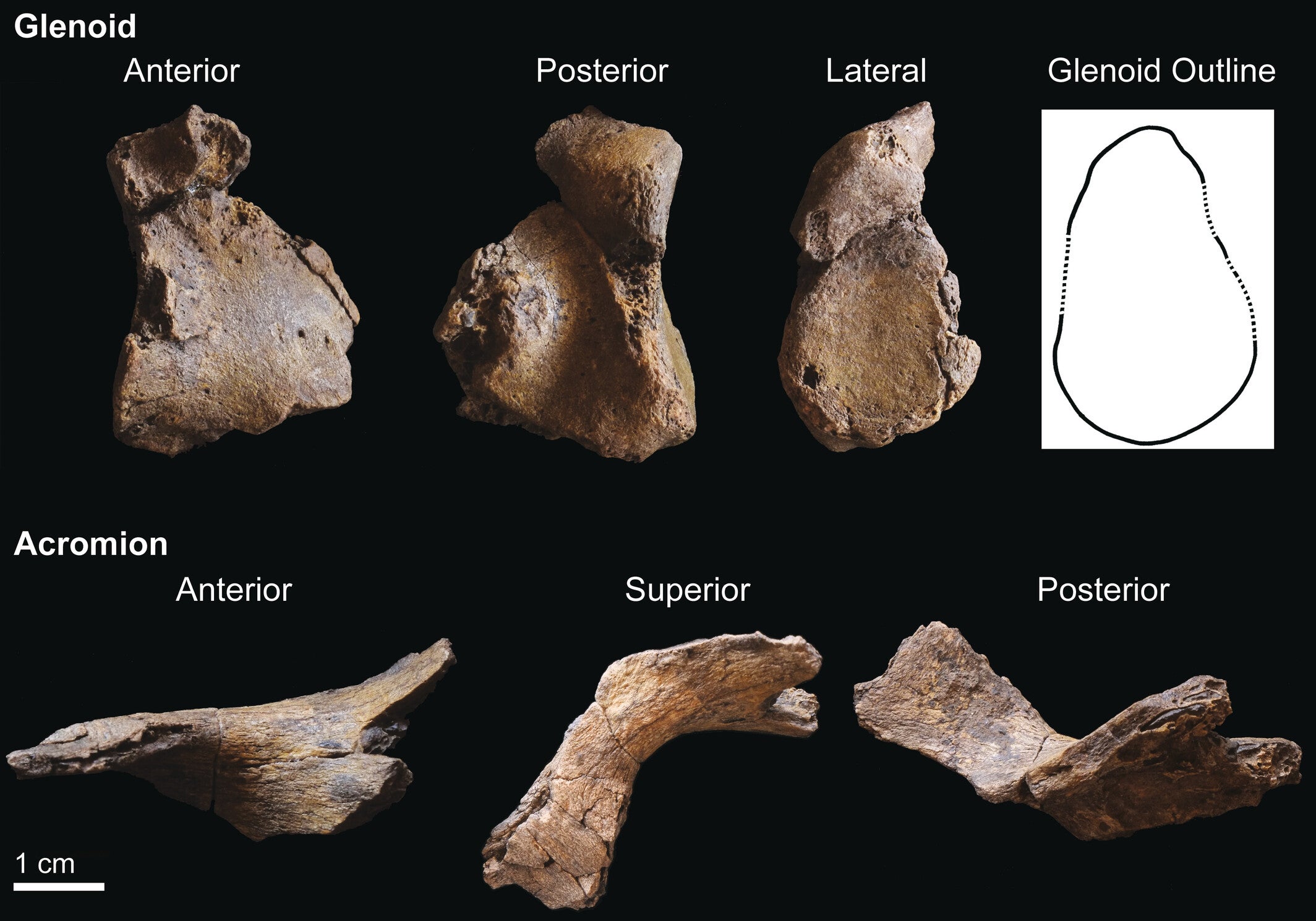

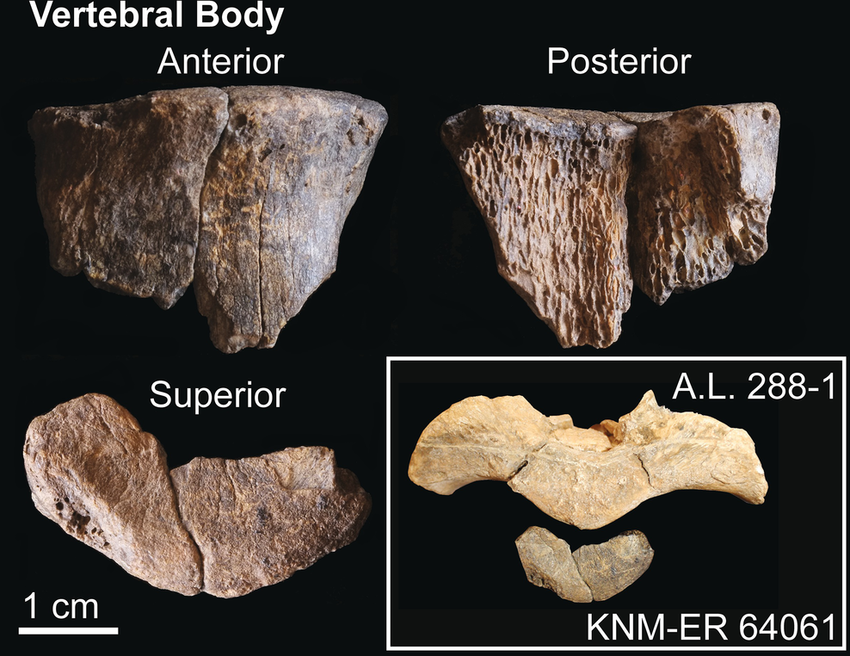

The new skeleton dates to between 2.02 and 2.06 million years ago. It includes both clavicles, scapular fragments, both humeri, both radii and ulnae, pieces of the pelvis, and part of the sacrum. That list reads like a map of the upper body, from collarbones and shoulder blades down to the hips.

The teeth matter as much as the bones. Researchers have often struggled to link isolated limb bones to diagnostic remains like teeth. Here, the associated mandibular teeth provide that anchor, making it far easier to argue the entire set belongs together.

The discovery began in 2012 during fieldwork led by Meave Leakey of the Turkana Basin Institute. What came first were bones that hinted at something larger. Later screening and excavations in the surrounding area turned up additional fragments.

The work did not end when the pieces reached a lab. Researchers had to reassemble the remains like a complex puzzle before they could compare shapes and surfaces. That slow, careful reconstruction set the stage for the detailed anatomical analyses reported now.

“I was invited to join the study in 2014 by Meave Leakey, but our morphological work on this skeleton would take another decade to complete,” said Ashley S. Hammond, an ICREA researcher at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP-CERCA) and a contributor to the study.

The paper reflects broad collaboration. The Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont (ICP-CERCA) is among the institutions named in the work. The long timeline also reflects the reality of paleoanthropology, where cleaning, fitting, and verifying fragments can take years.

“Our team’s analyses suggest the individual stood about 160 centimeters tall. We estimate a weight between 30.7 and 32.7 kilograms. In simple terms, this person was relatively short and very light compared with later members of the genus Homo,” Hammond told The Brighter Side of News.

“The limb bones carry a more complicated message. Many details resemble Homo erectus and later Homo species. Yet the proportions and robustness do not match that later pattern,” he continued.

The arms appear proportionally longer and stronger than you would expect in Homo erectus. The forearm relative to the upper arm is also proportionally longer than in Homo erectus. That trait ties early Homo to older relatives like Australopithecus afarensis, which lived more than a million years earlier.

Researchers also report unusually thick cortices in the shoulder and arm bones. The cortex is the outer layer of bone. Thick cortical bone shows up in australopiths and some other early Homo fossils. In this skeleton, it adds to the picture of strong upper limbs relative to body size.

These mixed signals matter because big adaptive changes occurred between earlier hominins and the appearance of Homo erectus. Homo habilis sits near the center of that story. A body that looks partly like later Homo and partly like older hominins suggests evolution did not move in one clean step.

The researchers say the upper-limb traits could reflect a lifestyle that differed from that of later Homo erectus. Stronger, longer arms relative to body size can imply different daily demands. The study does not claim a single behavior, but it does show the arms deserve attention.

“Homo habilis upper limbs have been coming more and more into focus, and KNM-ER 64061 confirms that the arms were fairly long and strong. What remains elusive is the lower limb build and proportions. Going forward, we need lower limb fossils of Homo habilis, which may further change our perspective on this key species,” Hammond said.

That line points to what you still cannot know from this skeleton. The recovered bones are largely upper body and pelvic elements. Without more lower limb material, researchers cannot fully describe how the legs compared with the arms, or how that balance shaped movement.

The study also carries a note of loss. The analyses were originally led by Bill Jungers, whose work helped shape the project. He died during the research, and the team notes his contributions remained central to the final study.

This discovery reshapes the fossil baseline for Homo habilis. With more complete postcranial evidence, researchers can test long-running ideas about when the human body began to look and function more like later Homo. That includes questions about size, limb proportions, and how different parts of the skeleton changed at different speeds.

The find also improves how scientists identify future fossils. When you have better reference bones, you can compare new fragments more confidently. That can sharpen species assignments in a time period when several early human relatives lived in the region.

Finally, this skeleton helps researchers ask smarter questions about behavior and ecology. The strong, relatively long arms hint at a way of life that may not match later Homo erectus. Future lower limb fossils, if found, could confirm or challenge that picture, and they could clarify how flexible early members of your genus really were.

Research findings are available online in the journal The Anatomical Record.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Two-million-year-old skeleton reveals homo habilis had strong, long arms appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.