A common cold can feel like a small thing until it is not. One day you feel fine, and the next you wake up congested, drained, and foggy. You may blame the virus. New research suggests you should also look at your own early defenses.

In a paper, researchers report that the body’s first response to rhinovirus often predicts whether you get sick, and how severe symptoms become. Rhinovirus is the most frequent cause of the common cold. It also plays a major role in breathing problems for people with asthma and other long-term lung conditions.

“As the number one cause of common colds and a major cause of breathing problems in people with asthma and other chronic lung conditions, rhinoviruses are very important in human health,” said senior author Ellen Foxman of Yale School of Medicine. “This research allowed us to peer into the human nasal lining and see what is happening during rhinovirus infections at both the cellular and molecular levels.”

The team’s work focuses on a simple idea with big consequences. The virus matters, but your body’s timing matters more. If your nasal lining responds quickly, the infection may stall. If it responds slowly, the virus can spread, damage cells, and trigger the misery you recognize as a cold.

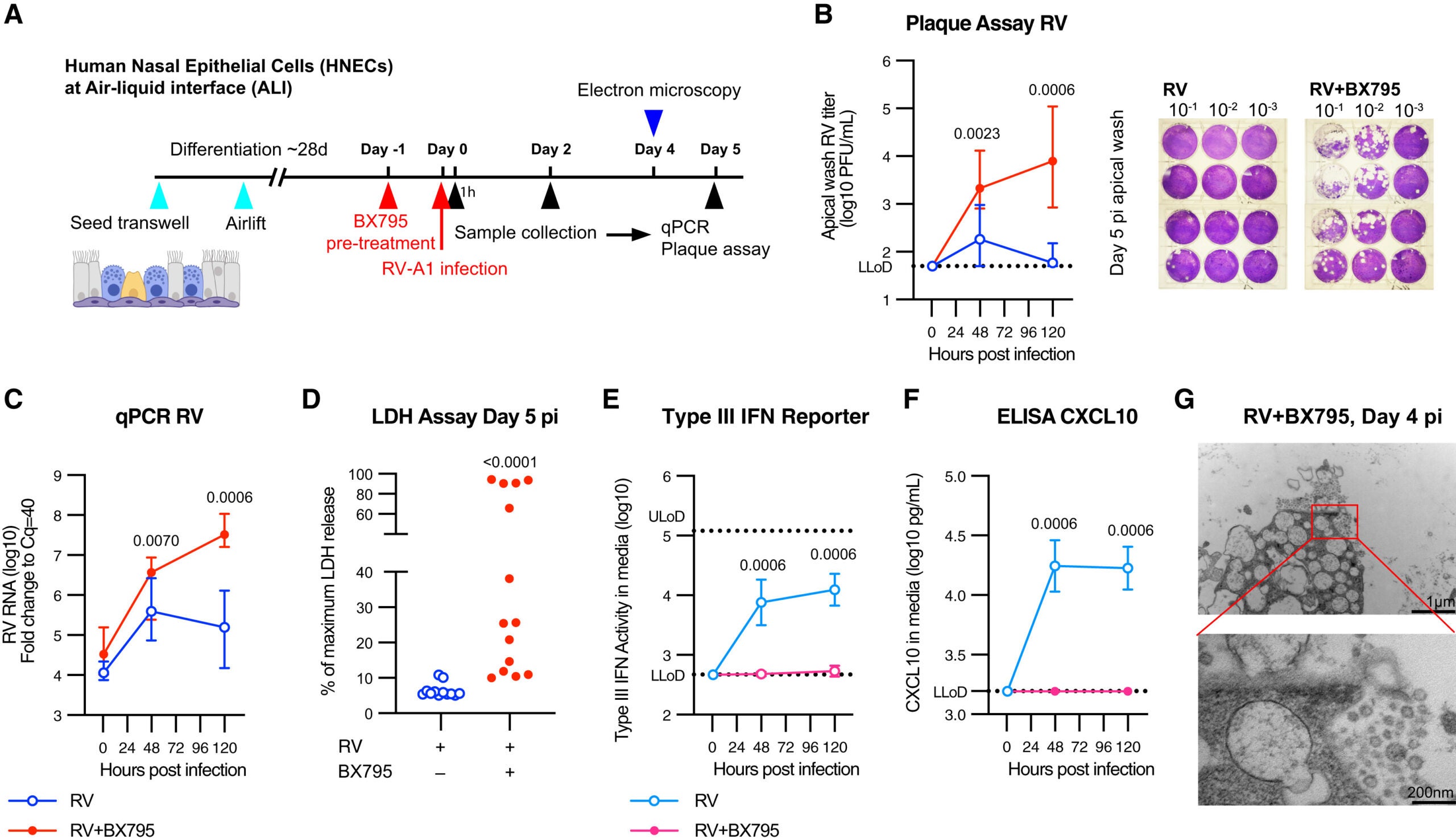

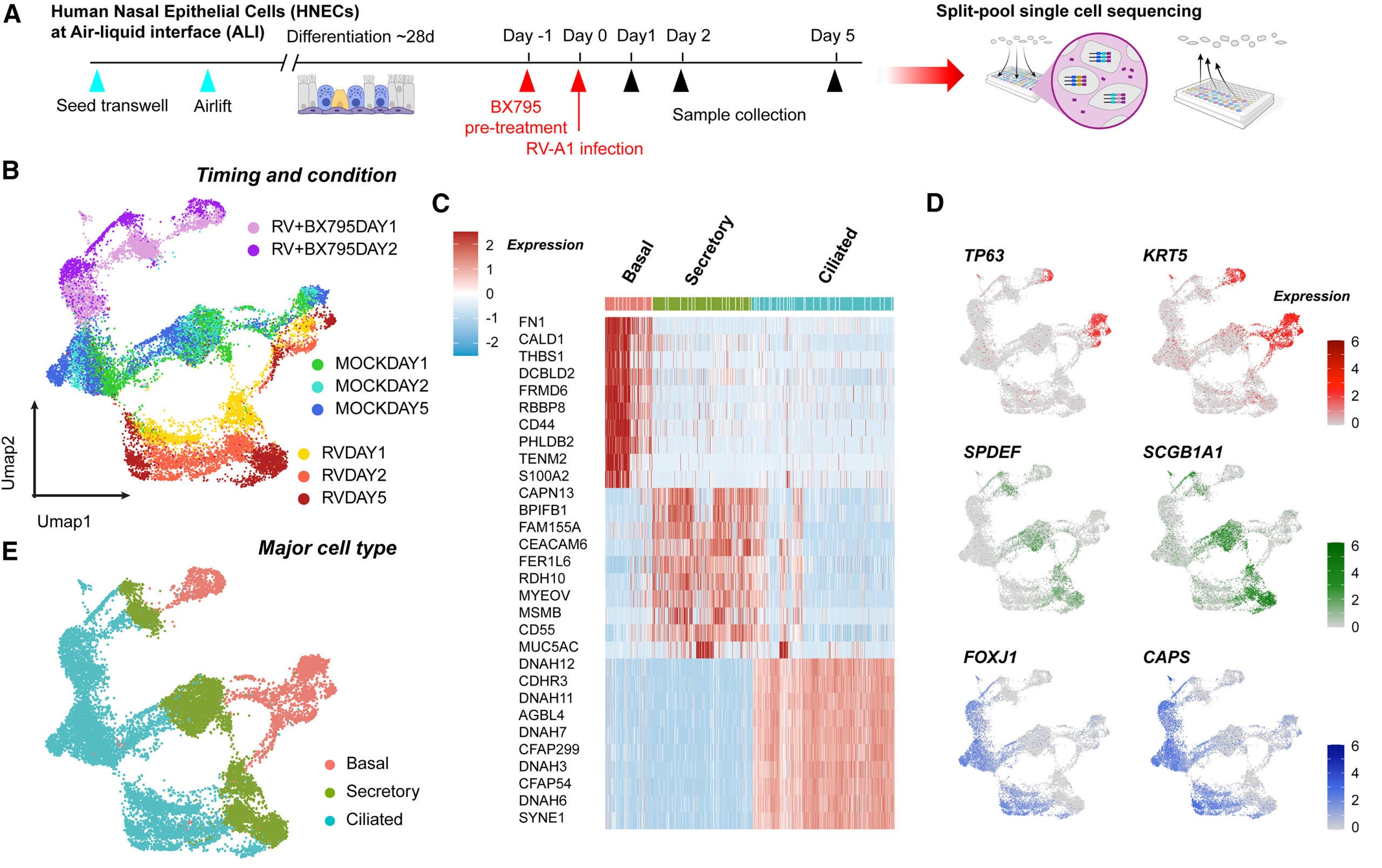

To watch this process unfold, researchers built lab-grown human nasal tissue. They started with human nasal stem cells, then cultured them for four weeks while exposing the top surface to air. That air exposure helped the cells mature into a tissue that contains several key cell types found in human nasal passages and airway lining.

The model included mucus-producing cells and cells with cilia, the tiny hair-like structures that help sweep mucus along. In your body, that movement helps carry trapped particles and germs away.

“This model reflects the responses of the human body much more accurately than the conventional cell lines used for virology research,” Foxman said. “Since rhinovirus causes illness in humans but not other animals, organotypic models of human tissues are particularly valuable for studying this virus.”

With this tissue in hand, the researchers could track how thousands of individual cells reacted during infection. They also tested what happened when key virus-sensing pathways were blocked.

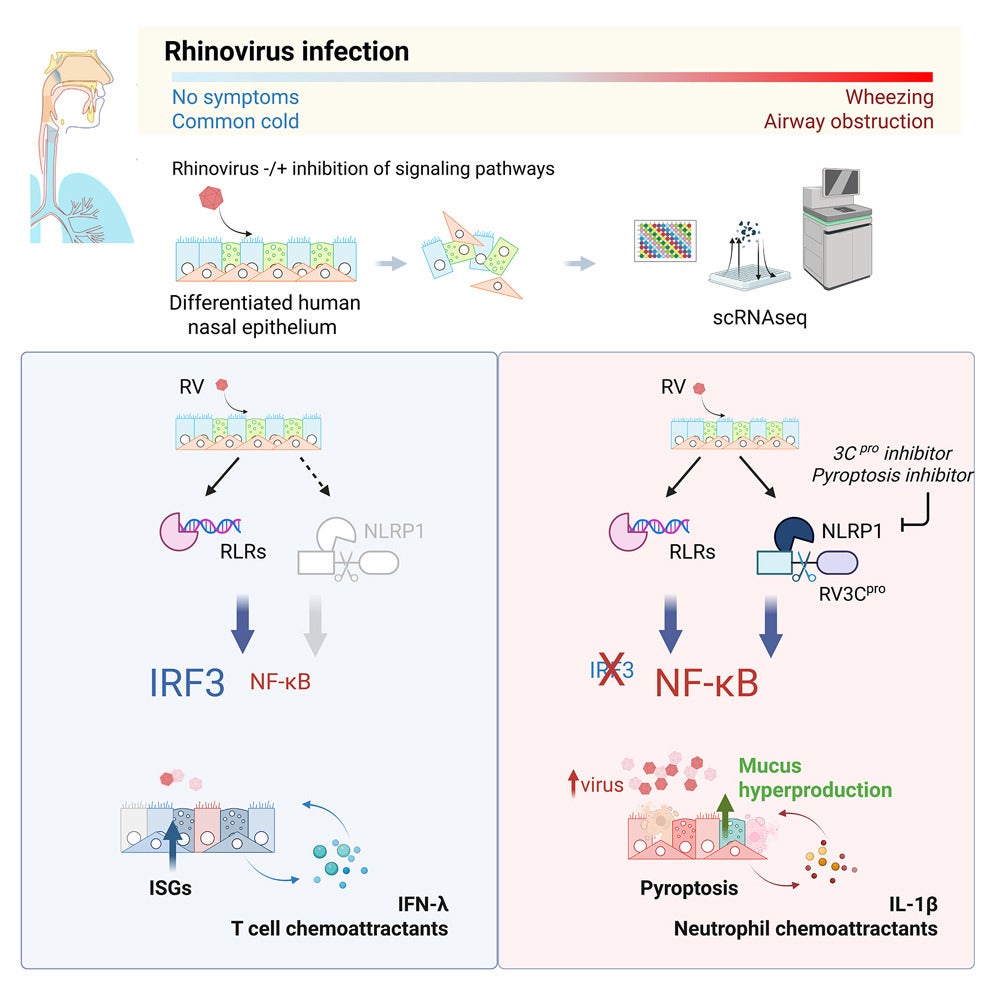

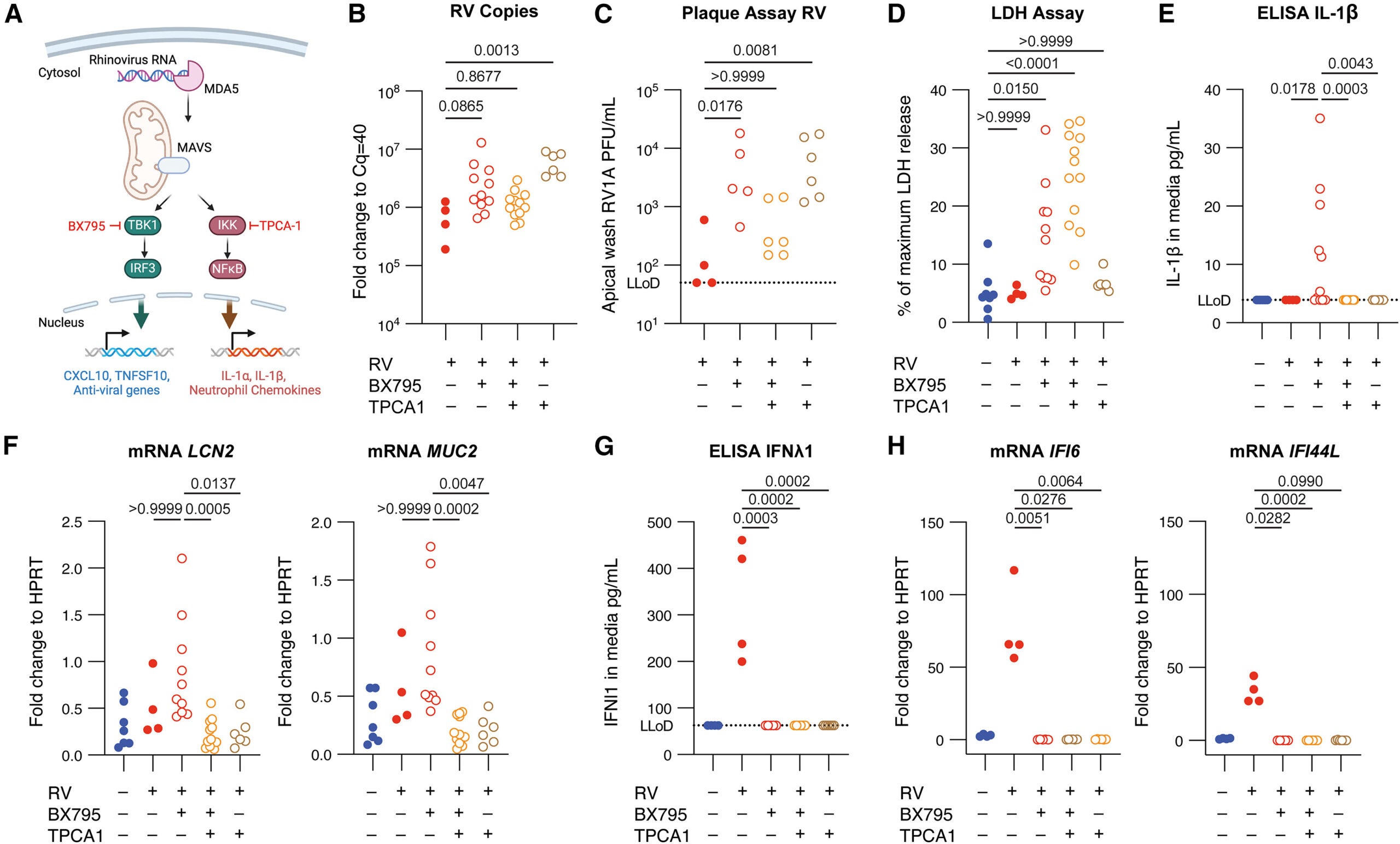

The study showed that when rhinovirus infects nasal lining cells, those cells do not fight alone. They coordinate. The central signal comes from interferons, proteins that help block virus entry and replication.

When cells detect rhinovirus, they release interferons. Those interferons then trigger antiviral defenses in infected cells and nearby cells. In effect, the tissue turns the local environment into hostile territory for the virus. If this alarm spreads fast enough, the virus cannot gain momentum.

“Our experiments show how critical and effective a rapid interferon response is in controlling rhinovirus infection, even without any cells of the immune system present,” said first author Bao Wang of Yale School of Medicine.

That detail is striking. The model did not include the full cast of immune cells that would arrive in a real infection. Yet the nasal lining still mounted a powerful defense. The researchers found that quick interferon activity could keep the infection contained.

When the team blocked this response experimentally, the story changed. The virus infected many more cells. The tissue showed damage. In some cases, infected organoids died. That shift suggests the virus can overwhelm the system when the early alarm fails.

The researchers also identified other responses that appear when viral replication rises. If interferons do not rein the infection in early, rhinovirus can trigger a different sensing system. That system drives infected and uninfected cells to work together in ways that may feel familiar to you.

The tissue can produce excessive mucus. Inflammation can rise. In the lungs, these reactions can contribute to breathing problems. These responses may start as protective moves, but they can also create discomfort and risk.

The researchers suggest these later pathways may offer targets for intervention. The goal would not be to mute your defenses. The goal would be to guide them toward a healthy antiviral response, and away from the kind of overreaction that worsens symptoms.

The team also stressed what this model cannot fully capture. The organoids contain limited cell types compared with your body. In a real cold, infection draws in other cells, including immune system cells, that join the fight and shape inflammation.

The researchers say the next step is to learn how other cell types and environmental factors in nasal passages and airways calibrate the response to rhinovirus. That includes understanding what makes one person’s early interferon response fast and another person’s slow.

“Our study advances the paradigm that the body’s responses to a virus, rather than the properties inherent to the virus itself, are hugely important in determining whether or not a virus will cause illness and how severe the illness will be,” Foxman said. “Targeting defense mechanisms is an exciting avenue for novel therapeutics.”

This way of thinking shifts the spotlight. Instead of chasing the virus alone, future research may focus on strengthening the early defenses that can prevent the cascade into a full cold.

If future work confirms these findings in more complex models and in people, the benefits could be practical and broad. A fast interferon response appears to be a critical early barrier against rhinovirus spread. That insight could steer drug development toward therapies that support that rapid antiviral alarm in the nasal lining.

The study also points to a second opportunity. When viral replication rises, the tissue can shift into heavy mucus production and inflammation. Those reactions may contribute to breathing problems in the lungs. Targeting those symptom-driving pathways could reduce suffering while preserving the antiviral defenses you need.

Over time, this research could help scientists explain why the same virus barely affects one person yet knocks another person down for a week. It may also guide approaches for people with asthma and chronic lung conditions, where rhinovirus infections can carry higher stakes.

Research findings are available online in the journal Cell Press Blue.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Why do some colds hit harder than others? appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.