An individual may become completely paralyzed because of any number of accidents that interfere with the functioning of the nerves in their body. People who have lost the ability to walk due to spinal cord injuries often continue to feel movement in their legs and arms, and the brain sends movement signals to their limbs.

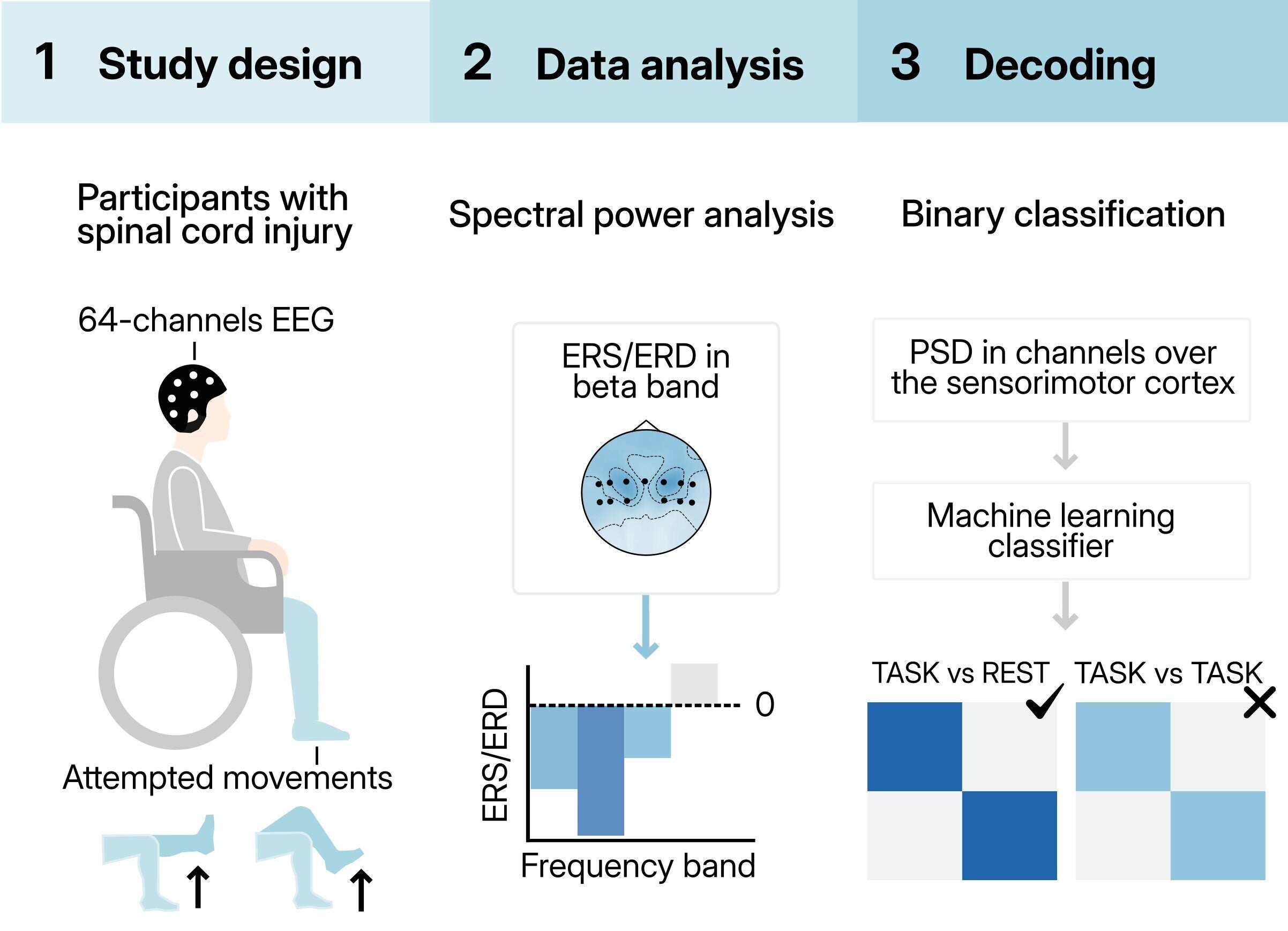

However, the spinal cord prevents the brain’s signals from reaching the legs and arms. Scientists in Italy and Switzerland are working together to figure out if they can read brain signals, like those from electroencephalography (EEG), that happen in the brain when we perform an action, and then send the read signals to a spinal cord stimulator to help restore mobility.

The research has been compiled and published in APL Bioengineering. Many universities in Europe contributed to this research, but it was coordinated by Laura Toni from Università Vita Salute San Raffaele and her team. The researchers at the various European universities have created a way to use EEG technology to read brain signal patterns and help restore voluntary movement to paralyzed limbs. You may see EEG sensors on people’s heads, but they are a non-invasive way to get information about how the brain is functioning.

“EEG does not require surgery and does not pose the same risk of infection as implanting an electrode directly into the brain,” Toni said about the delivery of electrical signals directly to the brain. “Could we avoid other surgical procedures and procedures that increase risk?”

Although it is a straightforward theory, it is relatively easy to understand. For example, when we are going to move a disabled limb, whether it is a hand or leg, our brains create many movement-dependent signals that tell the limb to move.

If we can successfully identify and decode those signals through EEG technology, we can send them to a spinal cord stimulator. This would activate the lower motor circuits to allow us to move the limb again, creating a bridge around the injured spinal cord.

People who have suffered spinal cord injuries have been successfully treated with electrical stimulation of the spinal cord to allow them to stand and walk. However, the major challenge is controlling the electric current that provides mobility. During day-to-day activities, the amount of stimulation sent to the legs must change based on the degree of movement required to achieve the goal of the movement. The effectiveness for motor-complete spinal cord injury patients is limited, as they have no remaining usable muscle signals.

A possible solution is to create a direct connection between the brain and spine. While there have been successful studies using electrocorticography with invasive procedures that open the skull, many patients feel the risk of these surgical procedures is not worth it. This is because walking may not have a high priority compared to other bodily functions, such as bladder control or sexual function.

EEG (electroencephalography) has proven to be safer, but it is less accurate when measuring movement signals from the body. The signals from the scalp are typically very weak and have many distortions, especially for movements of the lower limbs. Because the brain’s lower limb movement areas are deep in the brain within a central groove, they are much harder to identify compared to hand and arm movement areas.

“The brain primarily produces lower limb movements in the central part of the brain but primarily produces upper limb movements from the brain’s outer edges,” Toni explains. “In this regard, creating a correct spatial map of what you are trying to decode is easier for the upper limbs as compared to the lower limbs.”

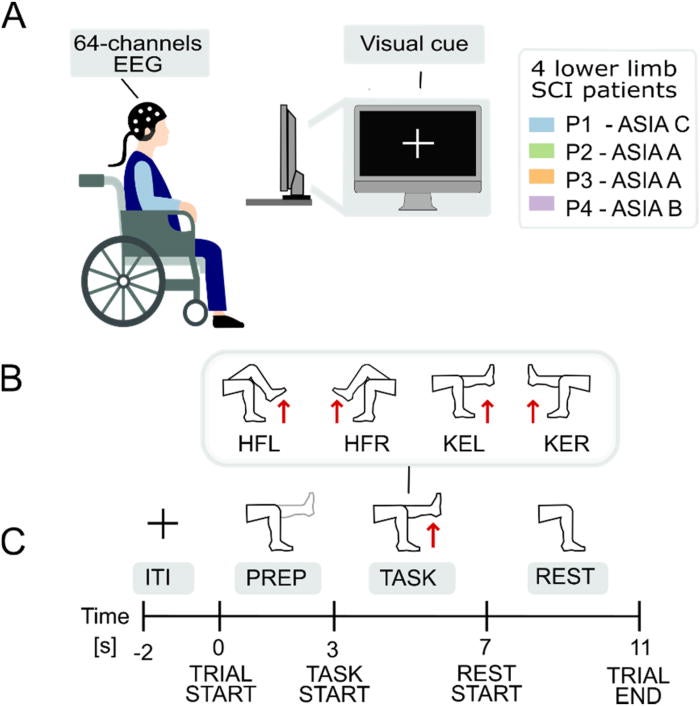

“To investigate what EEG could realistically accomplish, our research team conducted a feasibility study involving four participants who had severe spinal cord injuries. Of those participants, one had an incomplete spinal cord injury, while the other three had complete motor-complete spinal cord injuries. EEG data were collected during four separate recording sessions from each of the four participants,” Toni explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“The four participants were each asked to complete four different movement patterns that would reflect their normal walking patterns. These included left hip flexion (movement of a leg away from the body), right hip flexion (movement of a leg toward the body), left knee extension (straightening out), and right knee extension (straightening out),” she added.

While the legs of the subjects did not move during the experiment, the same neural activity associated with the movements during the experiment was present in the subjects’ brains. Researchers examined EEG brain signal power when the subjects were attempting to move and compared it to EEG signal power when the subjects were at rest.

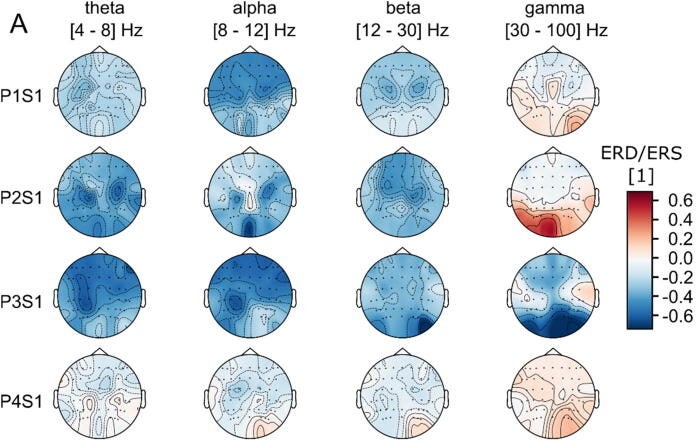

The researchers focused on common frequency bands associated with EEG brain signal power, specifically theta, alpha, beta, and gamma. At all frequency bands analyzed, movement attempts were associated with a decrease in EEG signal power, producing so-called desynchronization, in the theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands. Occasional increases in gamma were detected in EEG signals obtained from subjects undergoing very little or no movement attempts.

These patterns of brain activity were most prominent in the central areas of the scalp corresponding to areas of sensorimotor processing. However, the EEG signals were very different from subject to subject and from session to session, reflecting the difficulty in decoding EEG activity associated with the lower portions of the body.

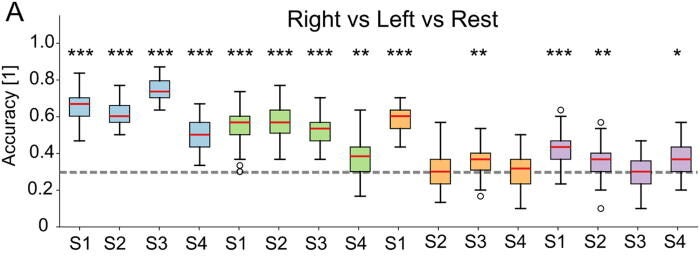

The second part of the study involved the development of a machine-learning model to classify EEG findings of lower-limb movement attempts versus EEG findings while at rest. The most basic task for the researchers was to separate EEG signals recorded when a subject attempted to move a limb from those collected when the same subject was at rest.

In two subjects, the machine-learning algorithm performed as predicted. In the remaining two subjects, performance was inconsistent at best. As the length of the analysis increased, accuracy also increased. However, it eventually plateaued. One participant waited just under a half-second for brain activity, while the other participants waited anywhere from 1 to 3 seconds for brain activity. In most cases, a length of around 1 second produced a balance between speed and reliability, assuming ideal conditions.

The research indicated that EEG could help establish reasonable goals based on practicality. EEG was most effective when determining whether someone was trying to move. These situations could be used to create automated stimulation programs that could lead to movement, such as activating walking or raising a person. It is unlikely, however, that researchers will develop fine-grained continuous control in the near future.

There are many factors, in addition to fatigue and concentration, that affect success in a clinic or gym. Each participant lived in the study’s setting and performed daily rehabilitation and research on the effects of epidural stimulation. This caused great variability between participants because of differences in daily levels of fatigue, concentration, and motivation. In addition, testing in an open-loop situation with no feedback made continuous effort more difficult to maintain than would occur in a closed-loop situation with regular feedback.

However, much of the variability described above can be attributed to typical daily life experiences. Therefore, any brain-computer system developed by researchers in the future should be able to operate effectively, even given fluctuations associated with human energy and mood. Since the study tested EEG in a variety of real-world situations, researchers were able to provide patients with a more realistic understanding of what to expect.

This research suggests that non-invasive EEG may provide a way for individuals with spinal cord injuries to regain a level of control over devices that support their movement. While EEG-based control will not replace existing rehabilitation, it may complement existing treatment techniques by providing a safer and more direct way for a patient’s brain to activate specific movements.

For patients with spinal cord injuries, the ongoing benefit of avoiding surgery provides another avenue to use assistive technologies. For researchers and health care professionals, this study identifies specific areas where EEG signals are most effective and where limitations exist. It may also suggest that simple, binary strategies are more feasible than complex strategies for now, although improvements to algorithms, training techniques, and feedback systems may continue to improve EEG signals.

Future enhancements in algorithm development, training, or feedback may strengthen EEG signals. Even small improvements can significantly enhance a person’s independence, reduce caregiver demands, and improve a disabled person’s quality of life for millions of people with spinal cord injuries.

Research findings are available online in the journal APL Bioengineering.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Noninvasive brain scanning could restore movement after spinal cord injury appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.