Repeated hits to the head do not have to knock you unconscious to harm the brain. Decades of research link long-term exposure to head impacts with memory loss, confusion, and dementia later in life. More than 100 former NFL players have been diagnosed after death with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. The condition has carried many names over the years, including punch-drunk syndrome and boxer’s madness, but the cause has remained the same.

Researchers at the University of Utah Health are investigating ways to prevent long-term brain injuries. Their preliminary studies indicate that near-infrared light therapy could help prevent subtle brain inflammation from repeated impacts- before an athlete shows any signs of injury. The findings were published in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

In recent years, concern has shifted from concussions alone to repeated head acceleration events (RHAEs). A repeated head acceleration event refers to a series of rapid forces applied to the head, often through contact with another player or by other external forces. RHAEs can produce no immediate signs of injury.

There are many RHAEs in football. Estimates suggest that for every diagnosed concussion, an athlete experiences between 125–440 RHAEs, and some players may sustain more than 70 RHAEs in a single regular season. Experimental results indicate that just one season of football for an athlete, on average, can cause measurable physiological changes in the brain.

Changes have been noted related to cognitive abilities, functional brain activity, white matter anatomy, and inflammation, even in the absence of a concussion diagnosis. The cumulative effects of all of these changes represent an increased likelihood of developing Traumatic Encephalopathy Syndrome (TES) and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE).

The area of interest regarding inflammation is located within the brain. The repeated impact associated with producing acceleration or deceleration of the head is thought to lead to the activation of immune system cells, which are located throughout the central nervous system.

In the short term, inflammation serves to promote tissue repair following injury. However, on a long-term basis, chronic inflammation can lead to neuronal cell death as well as disruption of communication between the various areas of the brain.

Detecting the inflammatory response that occurs within an athlete’s brain as a result of repeated head impacts is extremely challenging. Most commonly used Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans can be inconclusive at best regarding differentiating inflammation from edema (swelling) or other pathological changes.

“Our team used state-of-the-art diffusion-weighted MRI imaging techniques that can assess both the amount of inflammatory activity present in an athlete’s brain and the organization of white matter. By utilizing these imaging techniques, researchers were able to assess the subtle changes in brain structure and function before any clinical symptoms manifested,” Elisabeth Wilde, PhD, professor of neurology at U of U Health and the senior author on the study told The Brighter Side of News.

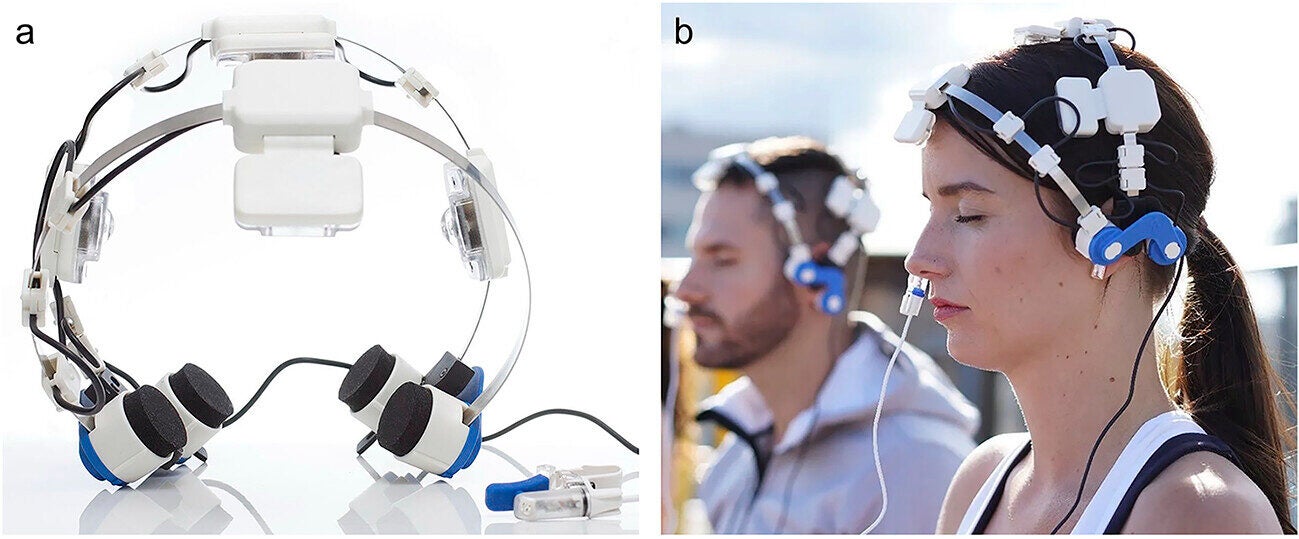

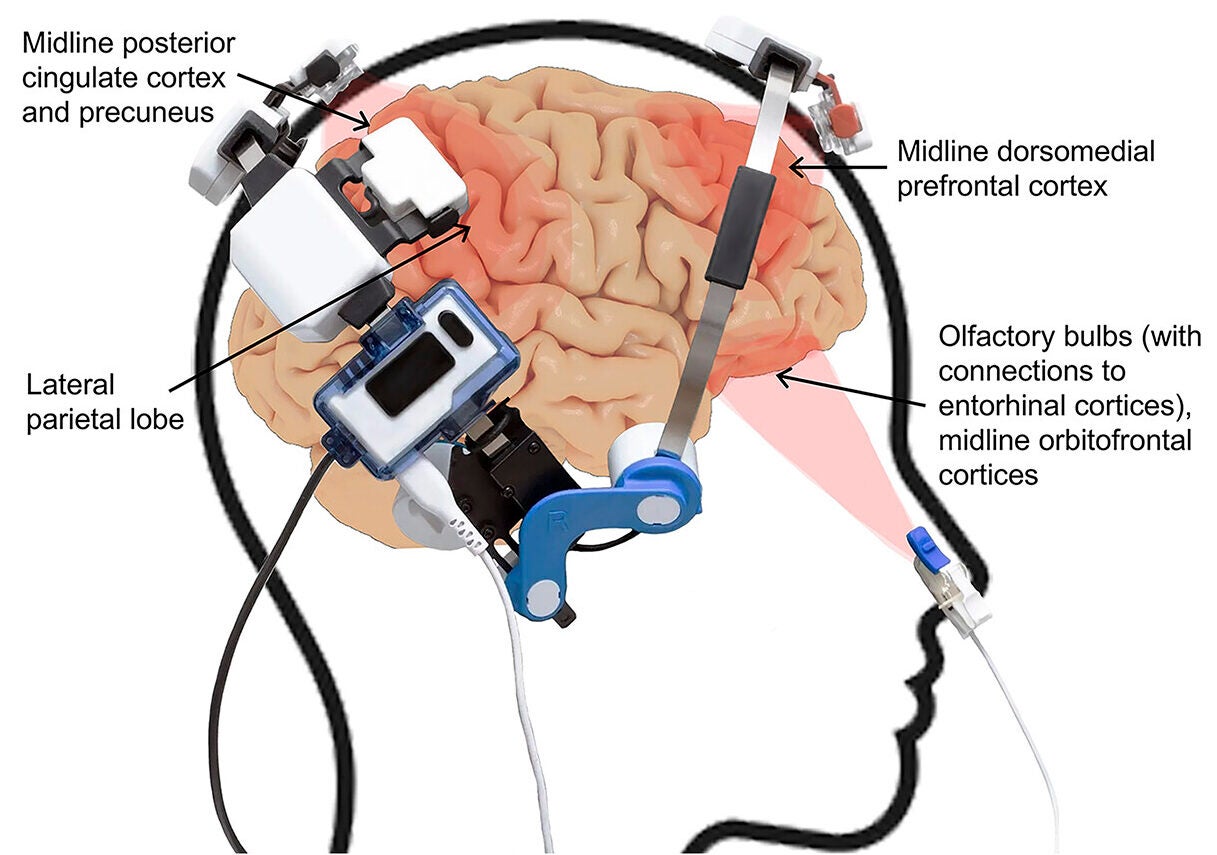

“We evaluated the effects of light as a therapy to reduce the deleterious effects of inflammation. Photobiomodulation is a therapy that uses a combination of red to near-infrared light that is administered to the athlete’s brain through either the scalp or nasal cavity,” she added.

In order for photobiomodulation to be effective, a sufficient amount of light energy is required to penetrate the skull and reach the outer layer of the athlete’s brain (i.e., occipital lobe). Only a small percentage of photons will actually reach their intended target.

Many laboratory studies indicate that certain wavelengths of red to near-infrared light can reduce the levels of inflammatory molecules (e.g., cytokines) in the brain and provide energy support for cellular energy production in neuronal cells.

A double-blinded clinical trial was conducted using a total of 40 NCAA Division I football players. Of the 40 enrolled participants, 20 received active treatment using a commercially available medical-grade device that delivered the photobiomodulation light using a headset and a small intranasal clip. The control group used a sham device that looked identical but produced no light.

The subjects self-administered a 20-minute session three times per week over the course of the 16-week study. At the conclusion of the study, there were 26 subjects remaining who had completed the study and whose MRI scans met quality control criteria after accounting for dropouts.

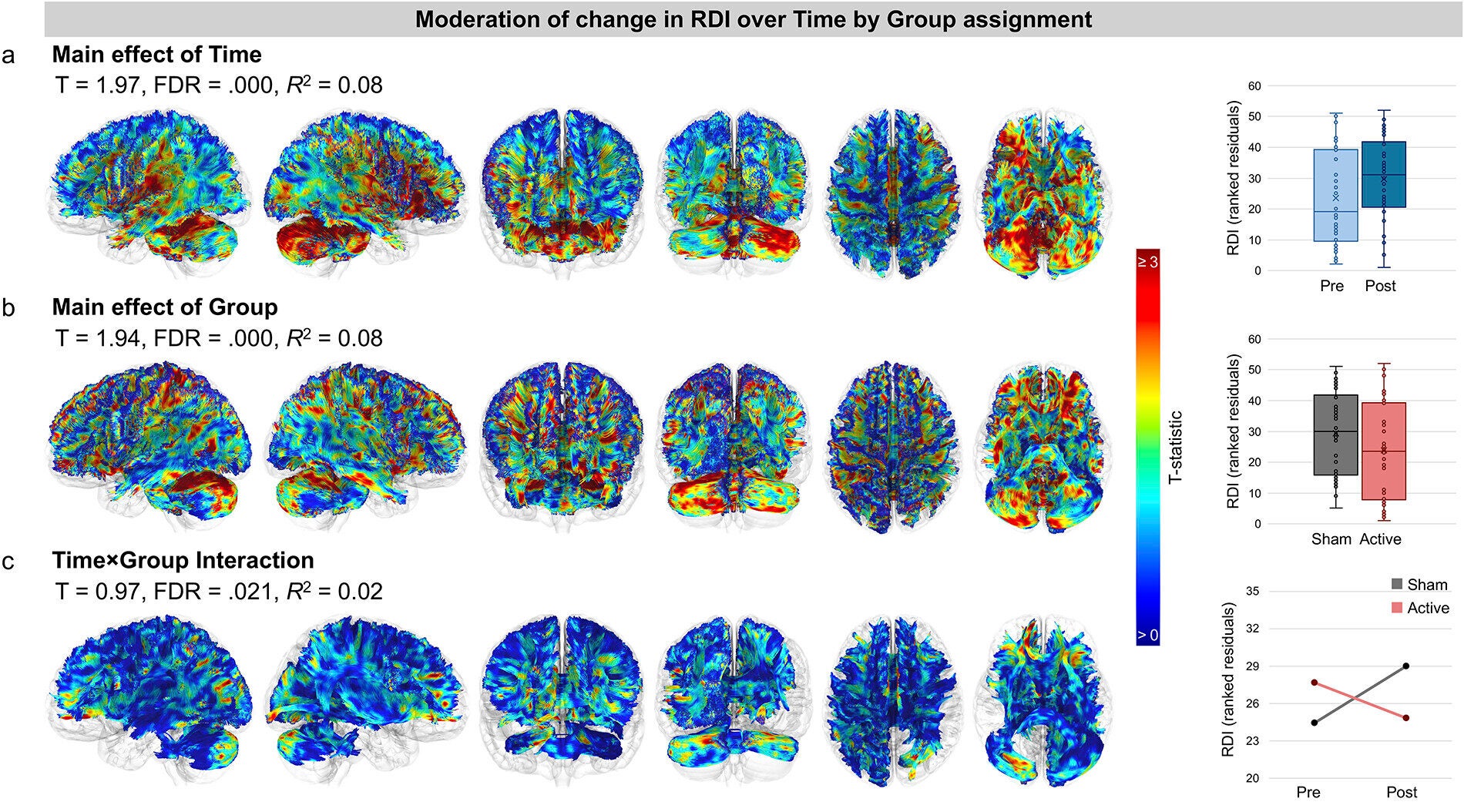

There were significant differences between the treatment and control groups at the end of the study.

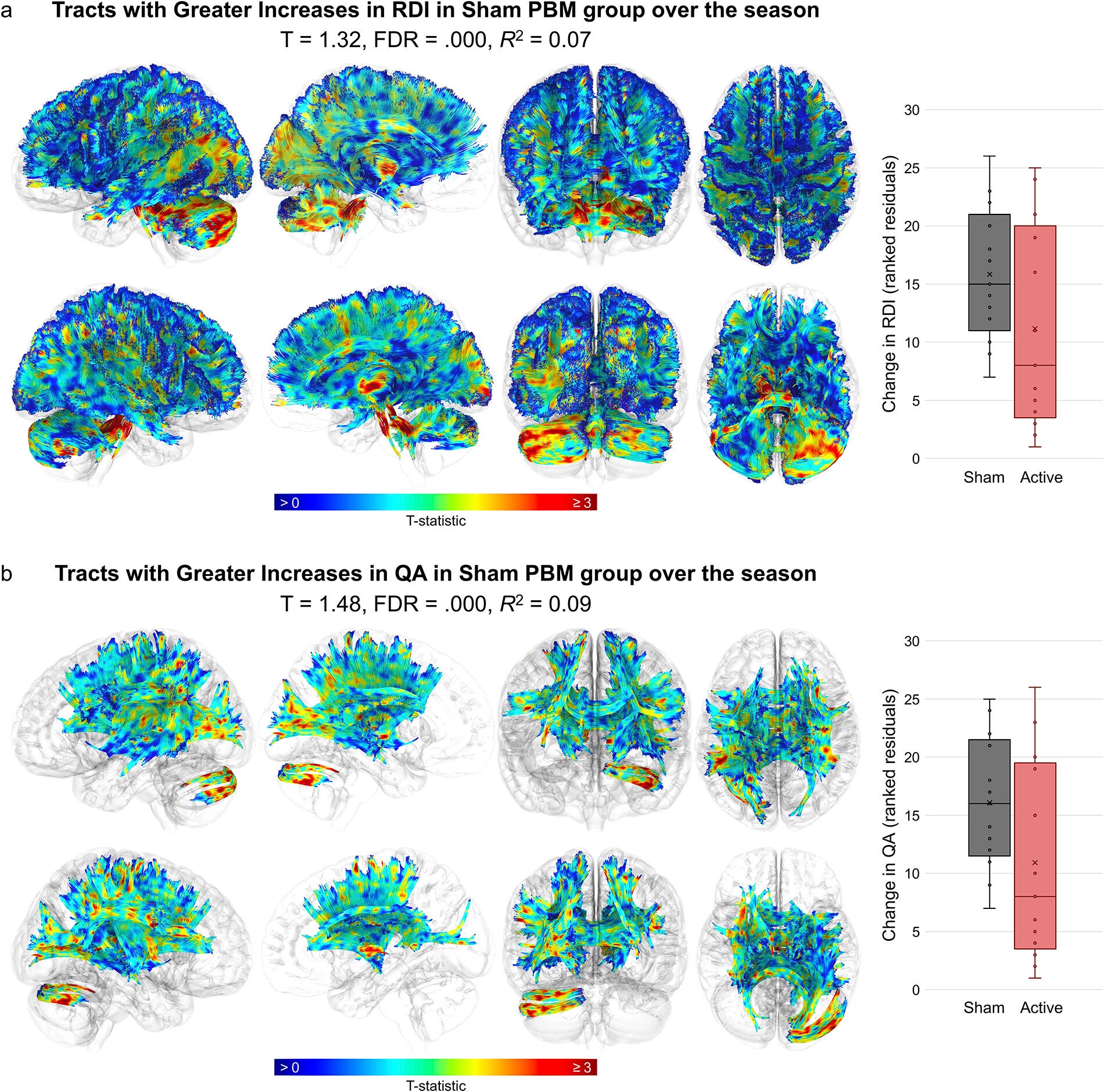

The results of the MRI scans taken before and after the study were strikingly different. Participants who had received sham treatment showed significant increases in inflammatory and white matter stress markers.

Across participants who received active light therapy, there was no increase in inflammation throughout the season. Some brain regions showed a decrease in inflammatory signals.

“My first thought was, ‘There’s no way this can happen,’” Hannah Lindsey, PhD, research associate in neurology at University of Utah Health and first author on the study said. “That’s how dramatic it is.”

The protective effects were evident in many areas of the brain, including those known to be vulnerable to accelerated forces.

The most severely affected areas of the brain were found in what are known as the cones of vulnerability. Examples of these areas include the brainstem, corpus callosum, basal ganglia, and long fiber pathways linking various regions of the brain.

In participants who did not receive active treatment, the changes were located almost entirely within the vulnerable zone. Conversely, in participants who received light therapy, the changes were limited and less pronounced.

“This is a new paradigm for prevention,” Carrie Esopenko, PhD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of Utah Health and a co-author of the study, stated. “We have been trying to determine how to make sports safer so that our children, friends, and family members can safely participate in sports for an extended period of time and receive the benefits of being active and happy.”

The study sample was small, and the differences in baseline inflammation levels between groups were due to chance. Larger studies are necessary to confirm the findings.

“I was very skeptical at the beginning of this project,” Wilde expressed. “We’ve observed consistent results from our multiple studies, so it appears to be fairly persuasive.”

The team is beginning a Department of Defense-funded randomized controlled trial with 300 individuals who have ongoing symptoms from TBI or concussive injuries. Recruitment is anticipated in early 2026.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Neurotrauma.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists develop a light-based approach to protecting football players’ brains appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.