There is an old saying in golf that players drive for show and putt for dough. Yet at the highest levels of competition, distance off the tee can decide tournaments. New research from the University of Kansas suggests that faster drives are closely tied to measurable physical traits, especially lower-body power and rotational speed.

The study was conducted by Quincy Johnson (Assistant Professor, Health, Sport & Exercise Science), who is the Director of the Jayhawk Athletic Performance Lab at the University of Kansas. He, along with fellow KU researchers Yang Yang and Andrew Fry, and researchers from Oklahoma State University (Kira Ziola, Dawei Sun, Jonathan Moore, Paige Sutton, and Doug Smith), published their findings in the International Journal of Strength and Conditioning.

According to Johnson, “There is not a lot of scientific research on golf, but when the opportunity arose to support golf athletes with our unique expertise, we seized the chance and utilized what we had learned through our research to develop ways to help them increase their club head speed.”

The focus of the research was directed at NCAA Division I golfers from Oklahoma State University (OSU), one of the nation’s premier collegiate golf programs. Their men’s team won the 2025 national championship and currently holds the record for the most NCAA championships, with 12 titles. The researchers were looking for the physical attributes that enable golfers to generate faster swing speeds than those who produce average swing speeds by evaluating the individual characteristics of elite college golfers.

The group consisted of 21 golfers (10 men and 11 women) competing at an extremely high level in their respective national associations. The participants averaged just over 21 years of age. Average height was 5 ft 4 in and weight was about 148 lbs for women, while average height was 5 ft 8 in and weight was about 170 lbs for men. Although there was a difference in height and weight between the two genders, BMI was almost equal.

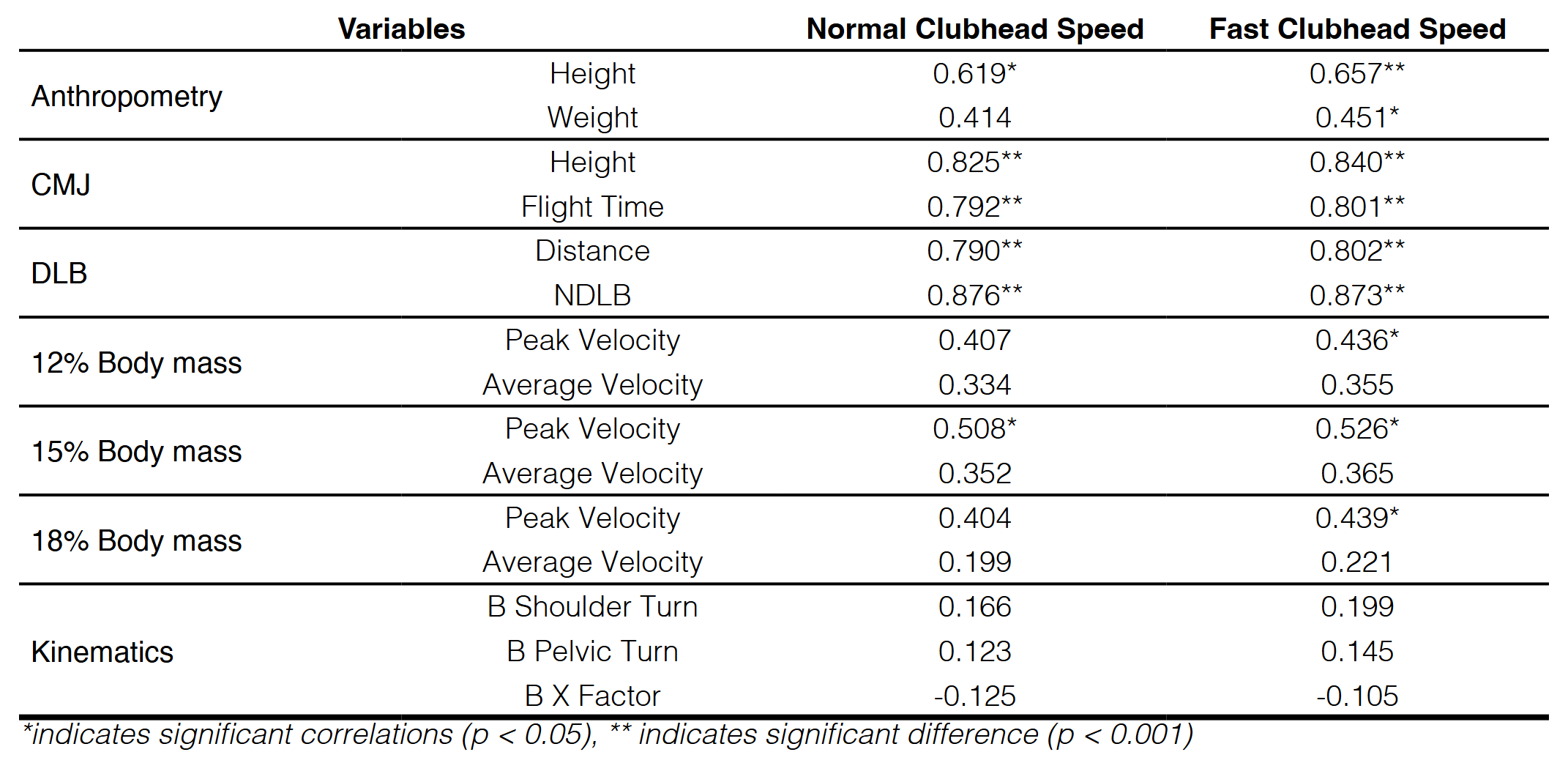

Measurements of height, weight, and average club head speed were collected during both normal and purposely faster drives. In addition, researchers measured lower-body power through vertical and lateral jump tests, which are considered terminal tests for golfers. These types of movements and performances are not typically associated with golf in the eyes of the public. The researchers also calculated upper-body rotational power using resistance devices set up for various loads.

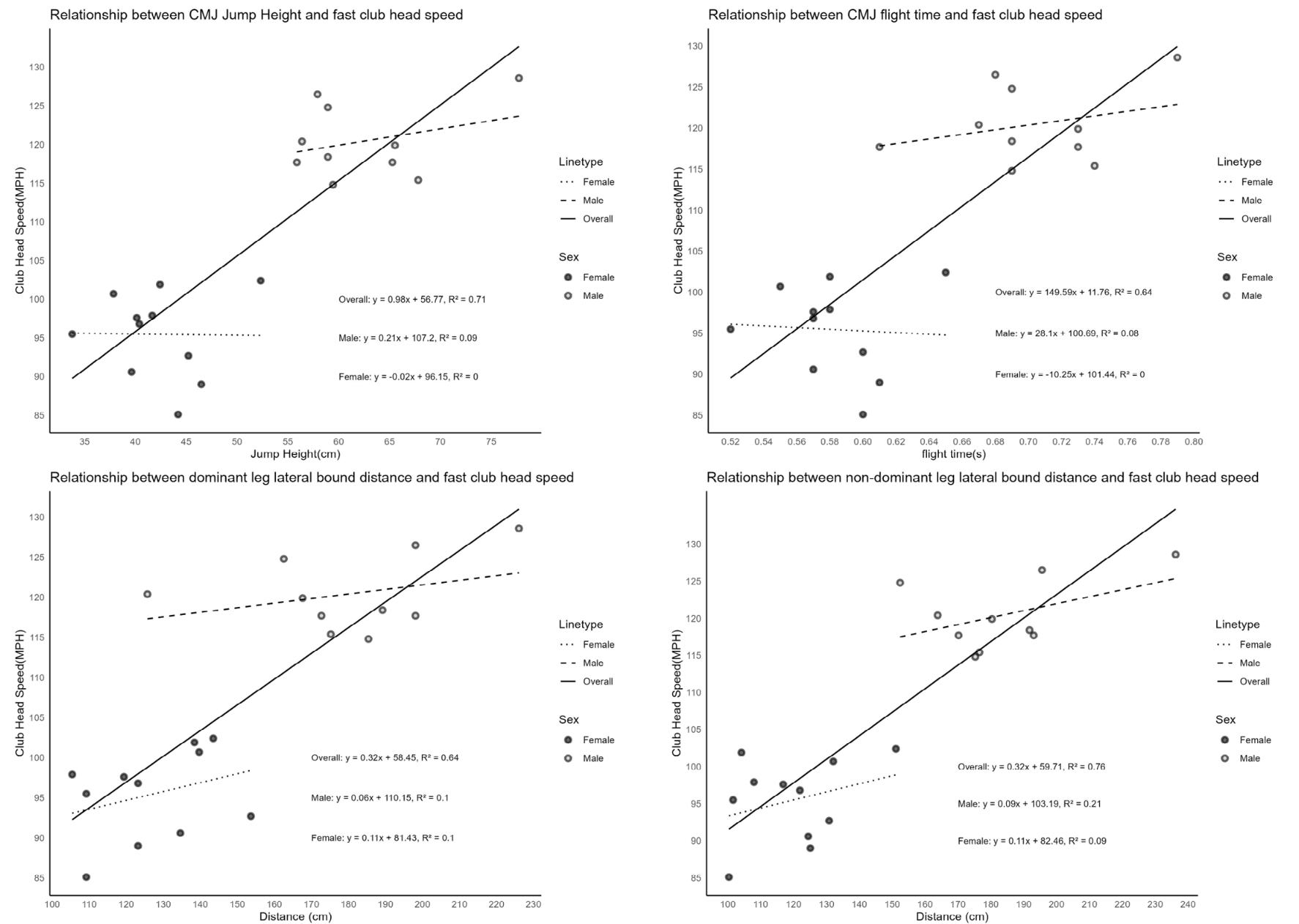

The potential links to golfer club head speed were therefore established through the use of jumping tests, among other measures. The relationship between both the vertical and lateral jump tests and the speed of the golf club head during both normal and faster swings was significant.

The lateral jump tests were of particular interest because of their potential to demonstrate how golfers transfer force across their bodies during a swing. The distance achieved by both the dominant and non-dominant leg jumps was significantly related to club head speed. Of particular interest was the strength of the relationship displayed by the non-dominant leg jump test. It was the strongest of all relationships observed.

Based on these findings, it appears that golf performance is based largely on producing force through the ground and the body, in addition to producing force vertically. While golf is not a vertical jumping sport, the lateral explosion of the body is also likely to influence the speed of the club head through impact.

“Club head speed is related to a golfer’s height and weight,” according to Johnson, “but also to a golfer’s ability to create power.”

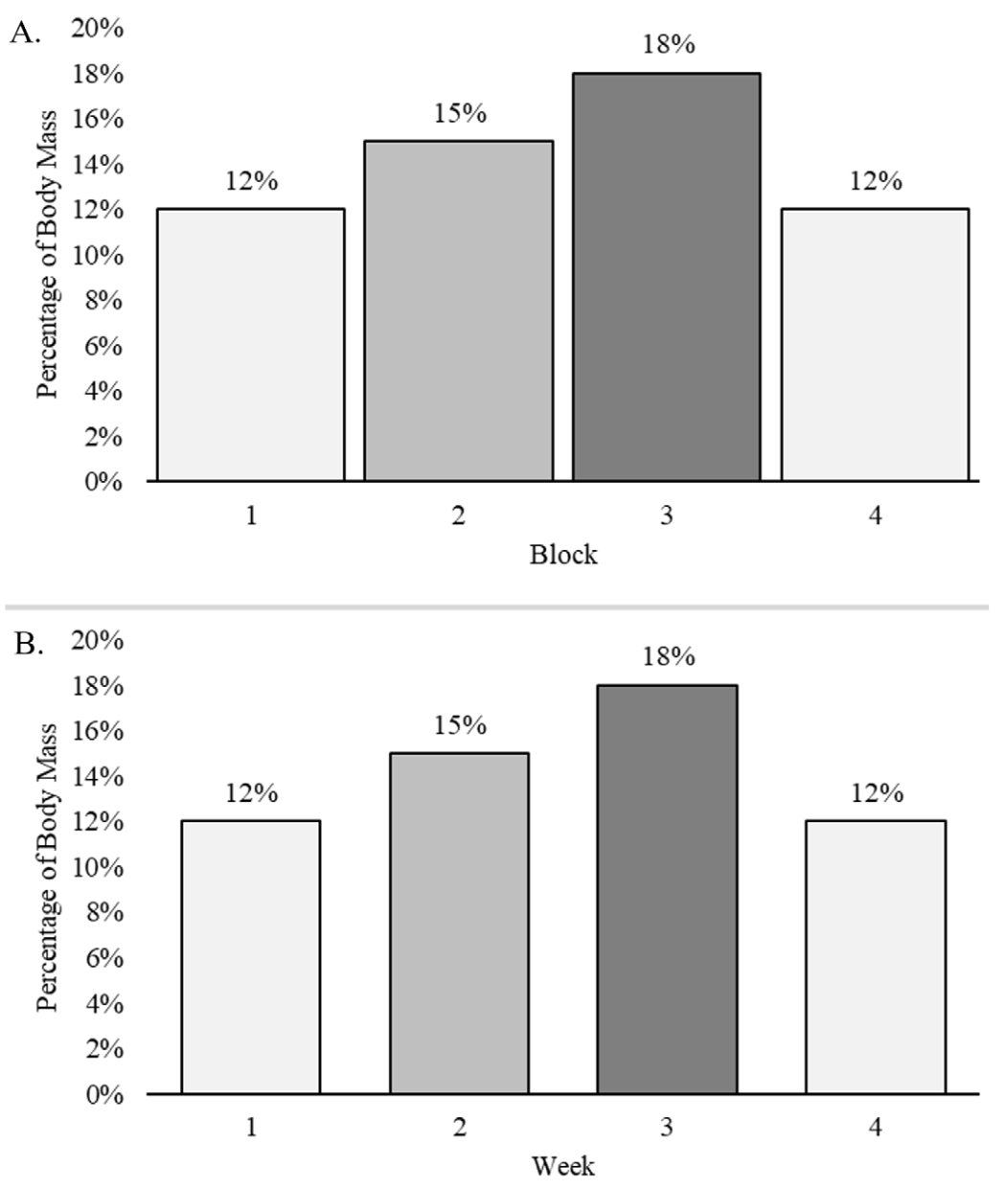

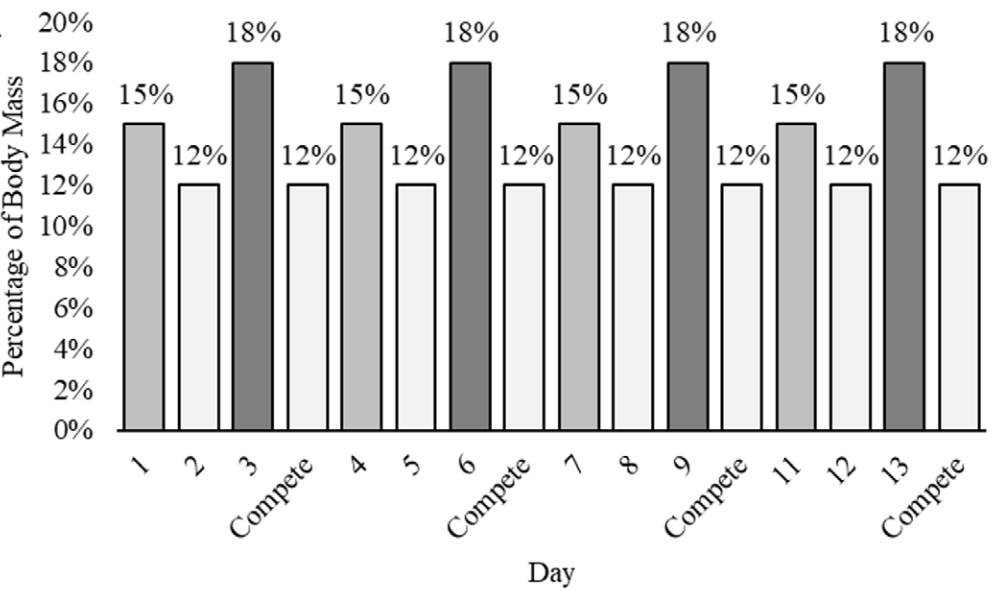

“We assessed upper-body rotational speed in the second phase of our research using a cable machine similar to those found in physical fitness facilities. Golfers were required to replicate their golf swing on the cable machine at three resistance levels expressed as percentages of body weight: 12 percent, 15 percent, and 18 percent. We measured how quickly the golfers could rotate their upper bodies under each resistance condition,” Johnson told The Brighter Side of News.

The researchers measured only peak rotational speed because it was the only metric that correlated significantly with club head speed. However, the strength of the relationship varied by resistance. Higher resistance (12 percent to 15 percent) and lower resistance (18 percent) showed the strongest correlations with club head speed, whereas moderate resistance levels showed the weakest correlation.

Although this approach is referred to as load velocity profiling and has been used in many other sports, such as football and rugby, it has not been extensively studied in golf. Consequently, the information obtained from this research is particularly valuable. The findings suggest that golfers may be able to increase club head speed by training upper-body rotational movements at specific resistance levels.

In terms of attributes that had less bearing on swing speed, few of the measured factors showed significant relationships. Neither shoulder nor hip range of motion demonstrated a strong relationship with club head speed in this group. Many components associated with swing mechanics, such as degree of shoulder turn, pelvic turn, and the difference between shoulder and pelvic turns, also exhibited weak or nonexistent relationships.

These results indicate that as athletes progress to elite status, their technical abilities may mature to a point where physical power, rather than added flexibility or mechanical adjustments, helps explain faster swings.

The collective findings present a more comprehensive view of the factors that drive elite driving performance. Athletes who were tall and lean, possessed explosive vertical and lateral power, and generated peak rotational speed under resistance produced greater swing speeds than the control group. Peak rotational speed during unloaded movement was also identified as an important factor when assessed accurately.

“If you are an athlete, coach, or sports performance professional interested in improving club head speed, this study identifies how your vertical jump and rotational velocity may significantly contribute to this,” said Johnson.

The authors recommended resistance training that targets strength, endurance, and power. This type of training includes exercises such as squats, lateral jumps, and controlled resistance rotation, all of which enhance the attributes most strongly associated with increased club head speed.

Johnson plans to expand his research to examine additional areas of golf performance. Driving is only one element of the overall game, but at the elite level, small differences in driving distance can separate great players from good players.

“Is there a physical prototype of the best golfers? I don’t know if we can conclusively say yes, but this does show how we identify strengths and how we develop training plans to improve a critical area of golf,” Johnson said.

Research findings are available online in the International Journal of Strength and Conditioning.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Jumping ability linked to faster golf swings and longer driving distance appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.