After a stroke, losing clear speech can feel like being locked inside your own thoughts. You may know exactly what you want to say. Your throat and mouth simply will not cooperate. Now researchers at the University of Cambridge say a soft, washable neck device could help you speak again; without brain implants or slow, letter-by-letter typing.

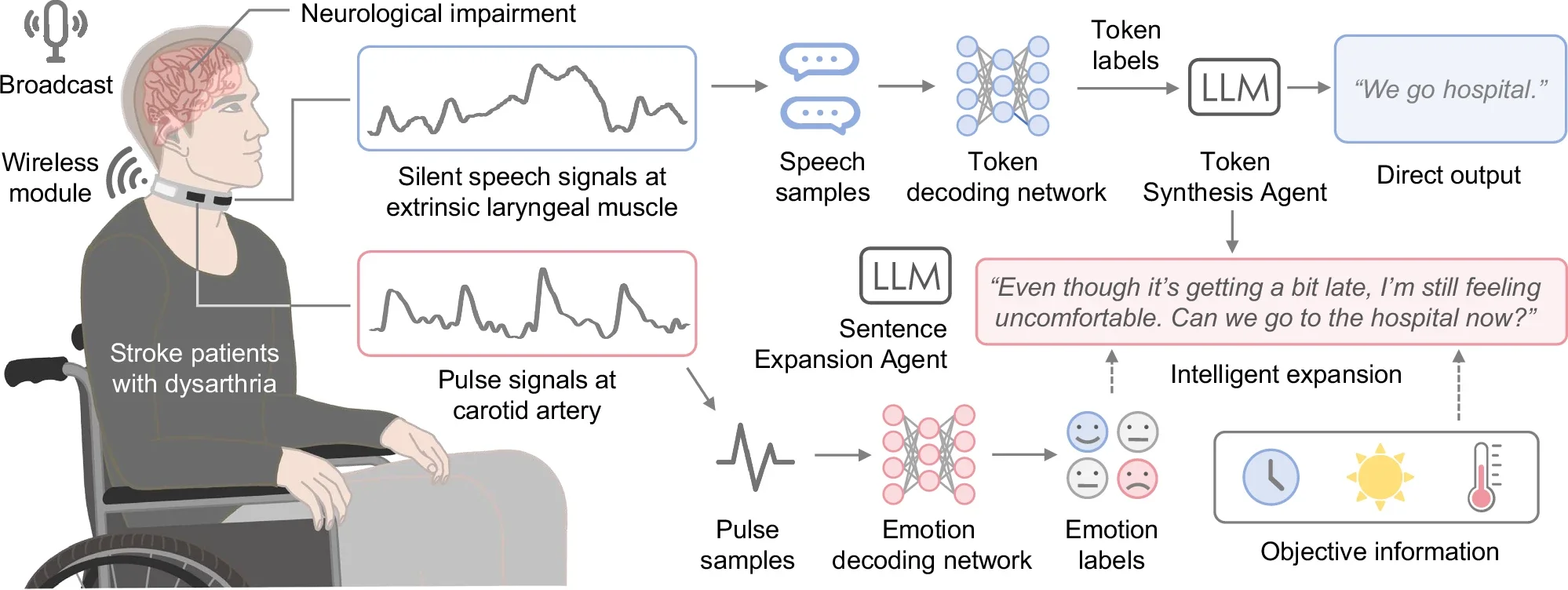

The wearable system, called Revoice, was led by Professor Luigi Occhipinti at Cambridge’s Department of Engineering. His team designed the device as a flexible choker that sits lightly around your neck. It reads two kinds of signals at once: tiny throat muscle vibrations linked to silent speech, and pulse patterns that offer clues about emotion.

“When people have dysarthria following a stroke, it can be extremely frustrating for them, because they know exactly what they want to say, but physically struggle to say it, because the signals between their brain and their throat have been scrambled by the stroke,” said Professor Luigi Occhipinti from Cambridge’s Department of Engineering, who led the research. “That frustration can be profound, not just for the patients, but for their caregivers and families as well.”

About half of stroke survivors develop dysarthria, or dysarthria alongside aphasia. Dysarthria weakens the muscles used for speech. The result can be slurred words, slow delivery, and short bursts instead of full sentences. Many people work with speech therapists for months, sometimes a year or longer. The drills can help, but everyday conversation still trips people up.

“Patients can generally perform the repetitive drills after some practice, but they often struggle with open-ended questions and everyday conversation,” said Occhipinti. “And as many patients do recover most or all of their speech eventually, there is not a need for invasive brain implants, but there is a strong need for speech solutions that are more intuitive and portable.”

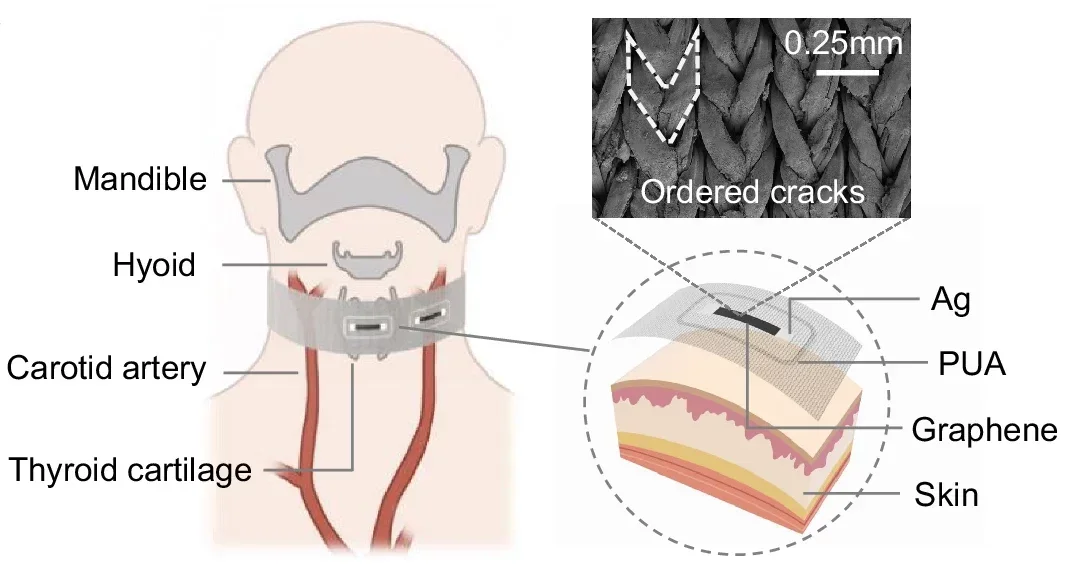

Revoice relies on ultra-sensitive textile strain sensors and a small wireless circuit board. One sensing channel sits near the center of the throat to capture vibrations from laryngeal muscles when you mouth words. Another sits near the carotid artery area to capture pulse signals.

The sensors use a printed graphene layer on elastic knitted fabric. The design helps the material detect extremely small skin-strain changes. The team also printed a rigid “stress isolation” layer around each sensing channel. That layer cuts down interference between channels and reduces strain caused by simply wearing the choker. In tests, the researchers reported that less than 1% of external strain made it into the interior sensor areas.

The device streams the two channels wirelessly and runs on low power. The study reports total power use of 76.5 milliwatts. With a battery rated at 1800 milliwatt-hours, the system is described as capable of lasting a full day.

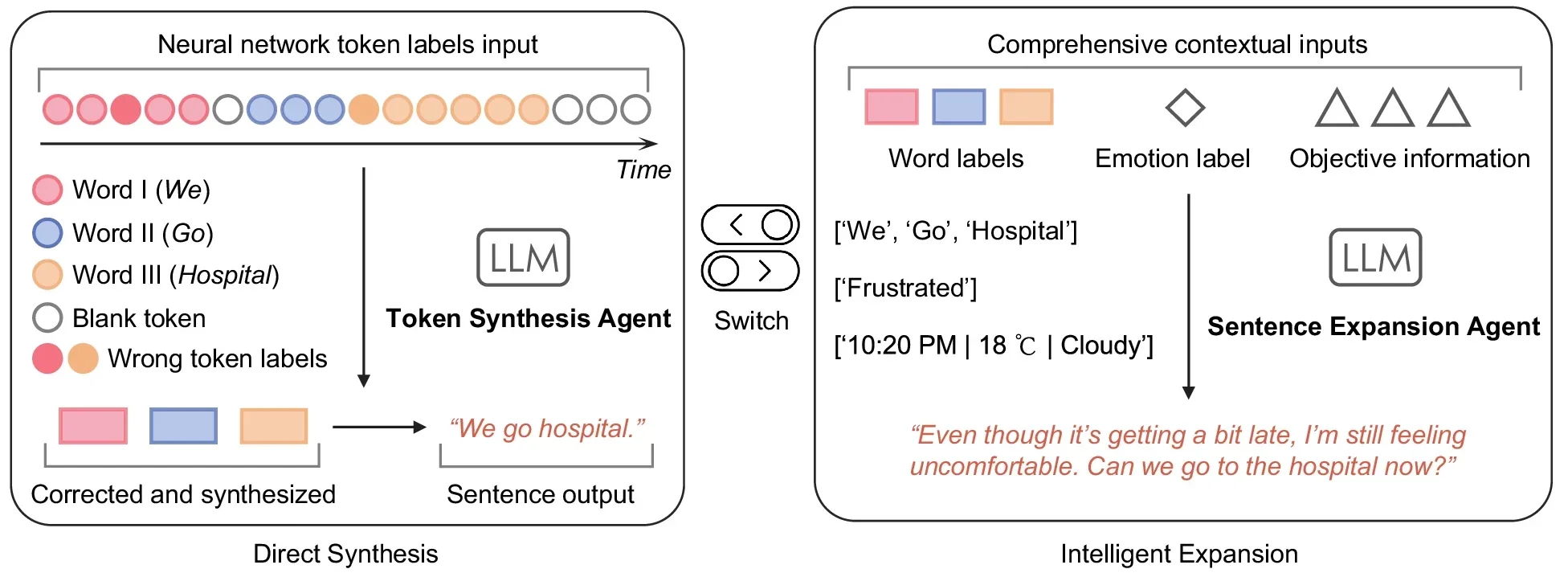

Revoice does not force you into a speak-stop rhythm. Earlier “silent speech” wearables often decode in fixed time windows, which can make communication feel chopped up. This system breaks speech signals into short tokens, about 144 milliseconds each, then decodes continuously. Tokens line up with fragments of words, not full words.

The signals move through two artificial intelligence agents. First, a token synthesis agent turns token labels into words and basic sentences. It uses contextual checks and a majority-voting approach to fix boundary errors, such as confusing a blank token with a nearby word token.

Second, a sentence expansion agent can enrich what you intended to say. If silently mouthing full sentences feels tiring, you can mouth a few words and let the system expand them into a complete thought. In the study, a simple gesture, two consecutive nods, lets you choose between direct output and expanded output.

The expansion agent uses emotional state plus objective context, such as time of day and local weather conditions. The system estimates emotion using pulse patterns; the study focused on three categories common for stroke patients: neutral, relieved, and frustrated.

The researchers say this matters because your message is rarely just the words. Tone and mood shape meaning, especially when you ask for help or describe pain.

In one example, “We go hospital” became “Even though it’s getting a bit late, I’m still feeling uncomfortable. Can we go to the hospital now?” The system inferred frustration from an elevated heart rate and recognized it was late at night. It then used that context to build a more complete sentence.

Working with colleagues in China, the team tested the system in a small trial with five stroke patients with dysarthria and 10 healthy controls. Participants wore the choker and mouthed short phrases. Under optimal conditions, the researchers reported a word error rate of 4.2% and a sentence error rate of 2.9%. The study also reports about a one-second delay between the end of silent expression and audio playback.

The work appeared in Nature Communications. Participants reported a 55% increase in satisfaction when using the sentence expansion option compared with direct output. The researchers also report that “core meaning” stayed stable, even as fluency and emotional alignment improved.

The study flags limits you should keep in mind. The vocabulary was defined, and the stroke cohort was small. The emotion decoding relied on a single signal type. The authors also note that performance can drift over time as neuromuscular control changes. In a six-month follow-up, word error rate increased, then returned to earlier levels after brief fine-tuning with five repetitions per word.

Even with those caveats, the approach aims at a clear clinical gap. Brain-computer interfaces can help some people, especially with severe paralysis. But they can require invasive recordings and complex setups. Other assistive tools may be easier to deploy, yet they often stay slow. For many stroke survivors who still have some control of throat and face muscles, the researchers argue that a comfortable, portable system could make everyday speech more natural.

“This is about giving people their independence back,” said Occhipinti. “Communication is fundamental to dignity and recovery.”

The Cambridge team says the same framework could also support people with conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and motor neuron disease. They are planning a clinical study in Cambridge for native English-speaking dysarthria patients to assess real-world viability, which they hope to launch this year.

If larger studies confirm these results, you could see speech support that feels closer to normal conversation. The biggest potential gain is speed. Instead of spelling words or navigating menus, you could mouth short phrases and speak in full sentences.

Clinicians may also benefit. More natural communication could help speech therapists track progress and adjust exercises in real time. Better day-to-day conversation could reduce isolation and stress, which often slow rehabilitation.

The researchers also suggest future versions could add multilingual support, recognize more emotional states, and run fully on the device for everyday use. That could widen access and reduce reliance on external hardware.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post AI-powered neck wearable helps stroke survivors speak again without implants appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.