For decades, scientists have searched for a safe way to reach deep parts of the human brain without cutting into the skull. That goal now feels closer. Researchers from University College London and the University of Oxford have developed an ultrasound device that can precisely influence deep brain regions in living people, without surgery. The system opens new paths for studying how the brain works and for treating conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, and essential tremor.

The work centers on a technology called transcranial ultrasound stimulation, or TUS. Unlike electrical or magnetic brain stimulation, ultrasound can travel deeper through the skull. Until now, however, it lacked the precision needed to target specific brain structures. This new system changes that, allowing scientists to focus on areas thousands of times smaller than before.

You rely on deep brain structures every moment, even if you never think about them. These regions help guide movement, shape emotions, and process sensory information. Yet studying them has always been difficult. Many existing tools either require invasive surgery or affect wide areas of the brain at once.

Deep brain stimulation, used for Parkinson’s disease, involves implanting electrodes directly into the brain. While effective, it carries surgical risks. Other non-invasive methods, such as magnetic stimulation, mostly reach the brain’s surface. The challenge has been finding a method that is both non-invasive and precise at depth.

Transcranial ultrasound offered hope because sound waves can pass through bone. Early systems, however, spread their effects too broadly. They influenced large regions instead of precise targets, limiting both research and clinical use.

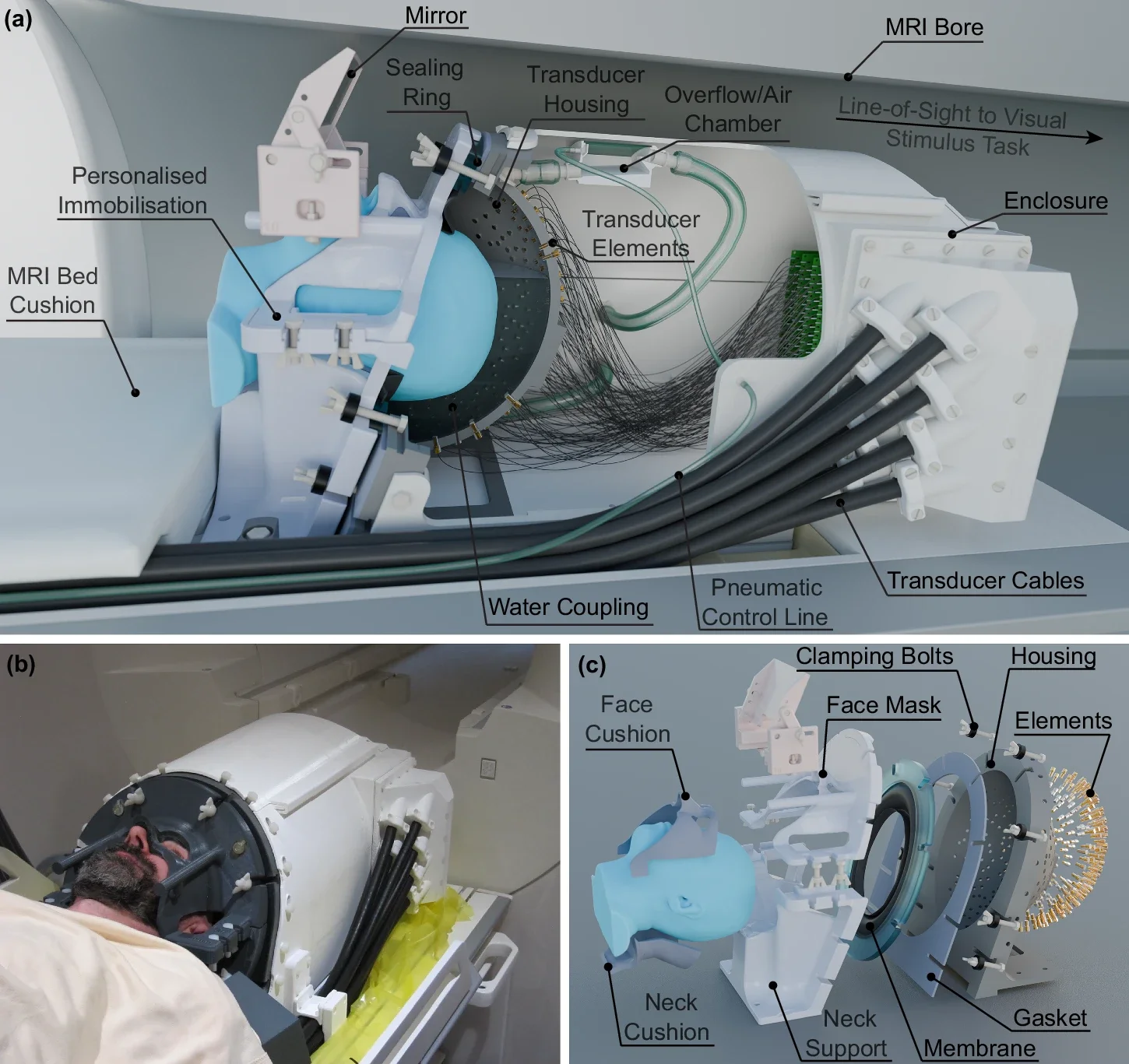

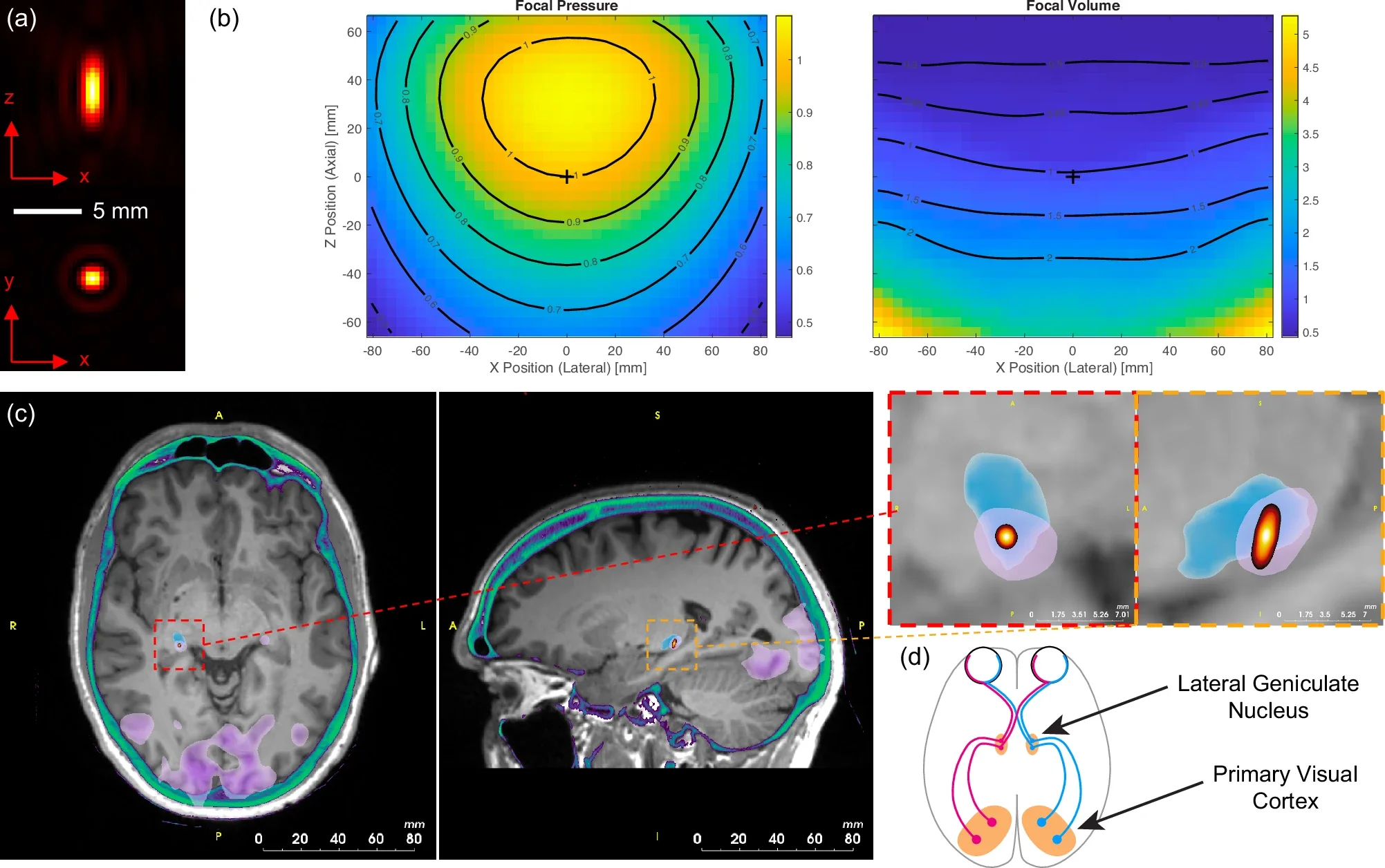

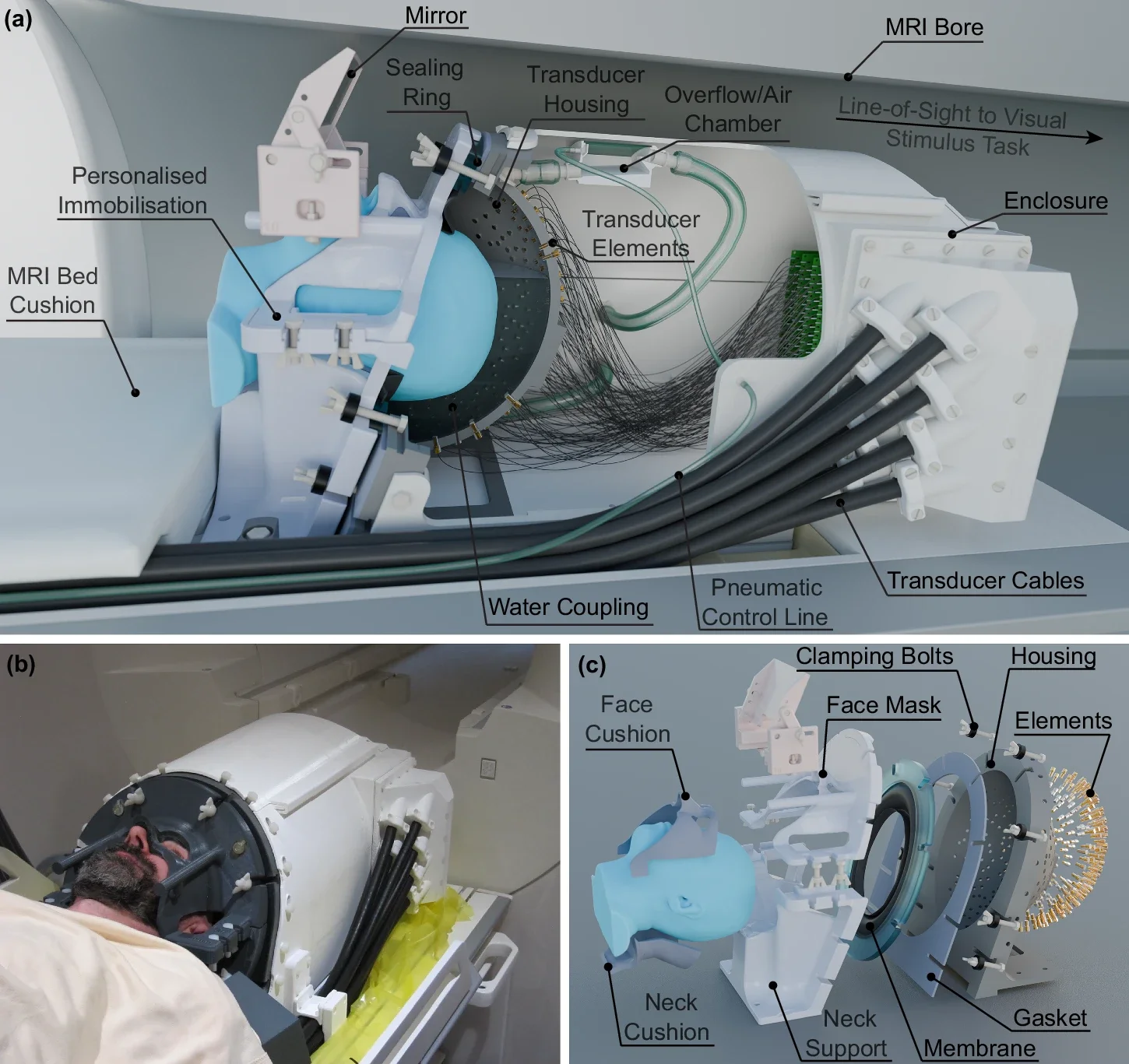

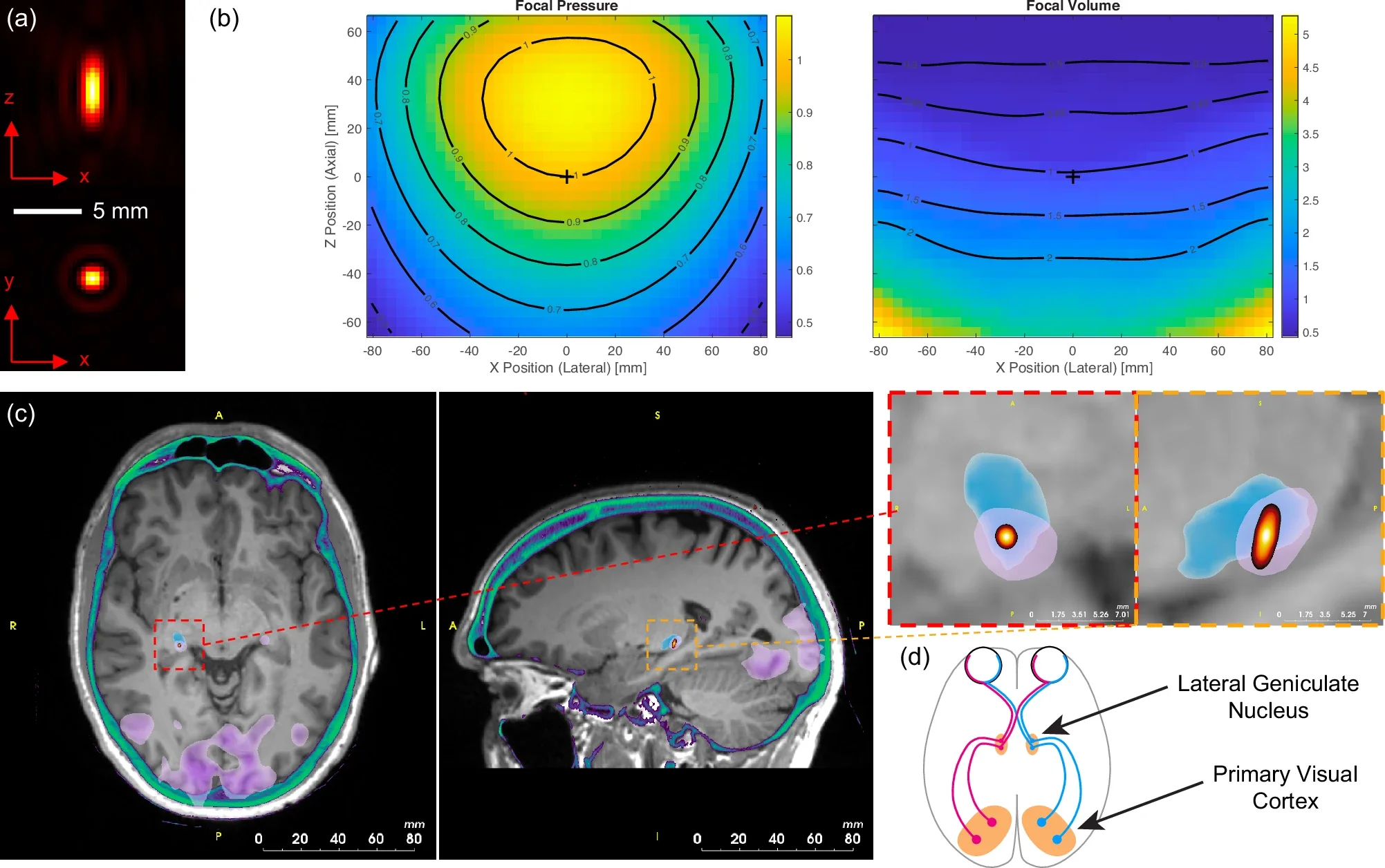

The new system looks a bit like a helmet. Inside it are 256 small ultrasound elements that work together. Each element emits gentle sound waves. When combined, those waves meet at a precise point deep in the brain. The result is a focused spot of stimulation that is extremely small, about 1,000 times smaller than what conventional ultrasound systems can achieve.

A soft plastic face mask helps keep the head still during use. This improves accuracy by preventing small movements that could shift the target. The team also used detailed computer models of each participant’s skull to guide the ultrasound beams. These models account for skull shape and thickness, which affect how sound travels.

Crucially, the system works alongside functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. This lets researchers watch brain activity change in real time while stimulation occurs. They can see whether the correct area responds, rather than guessing.

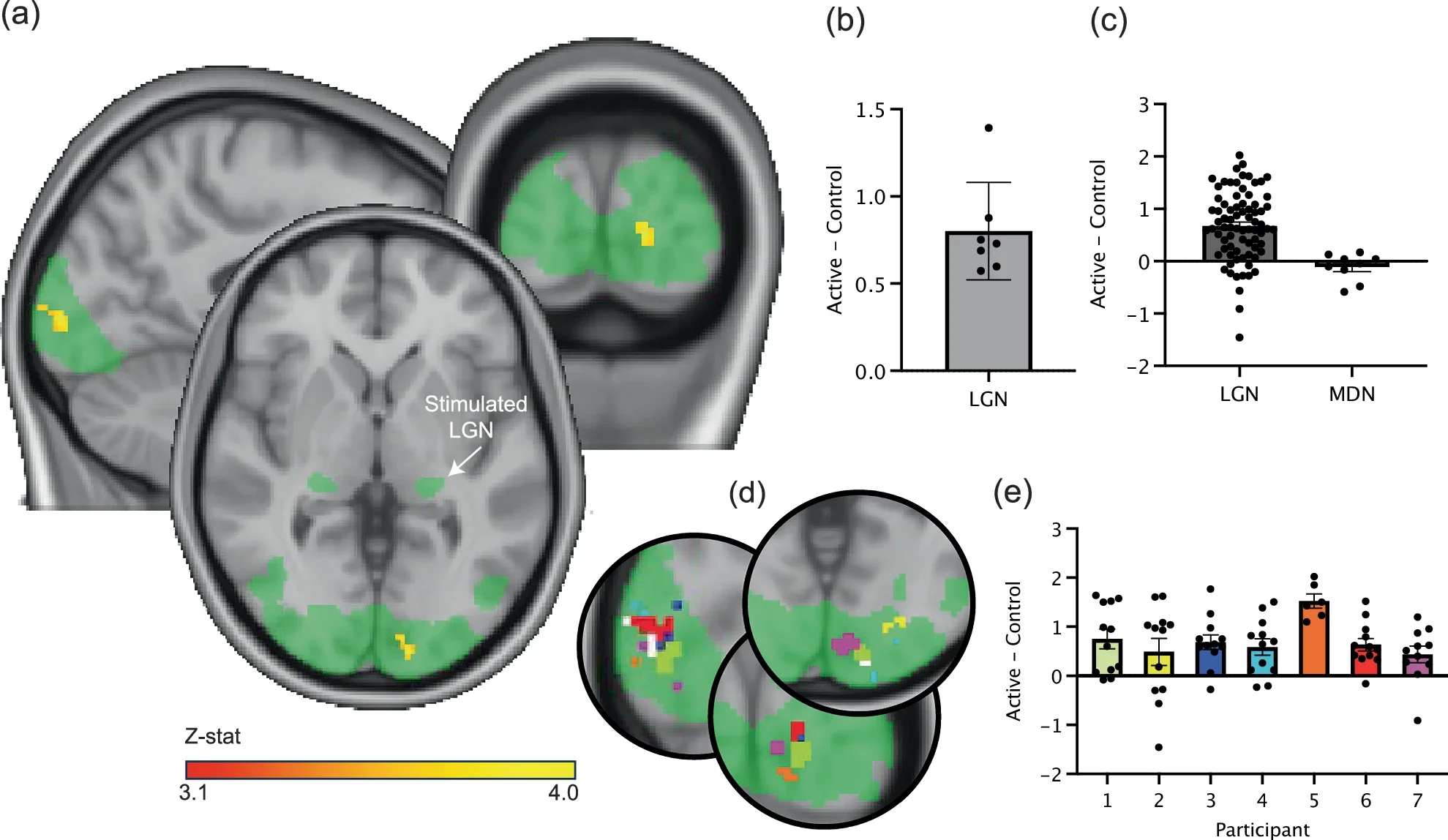

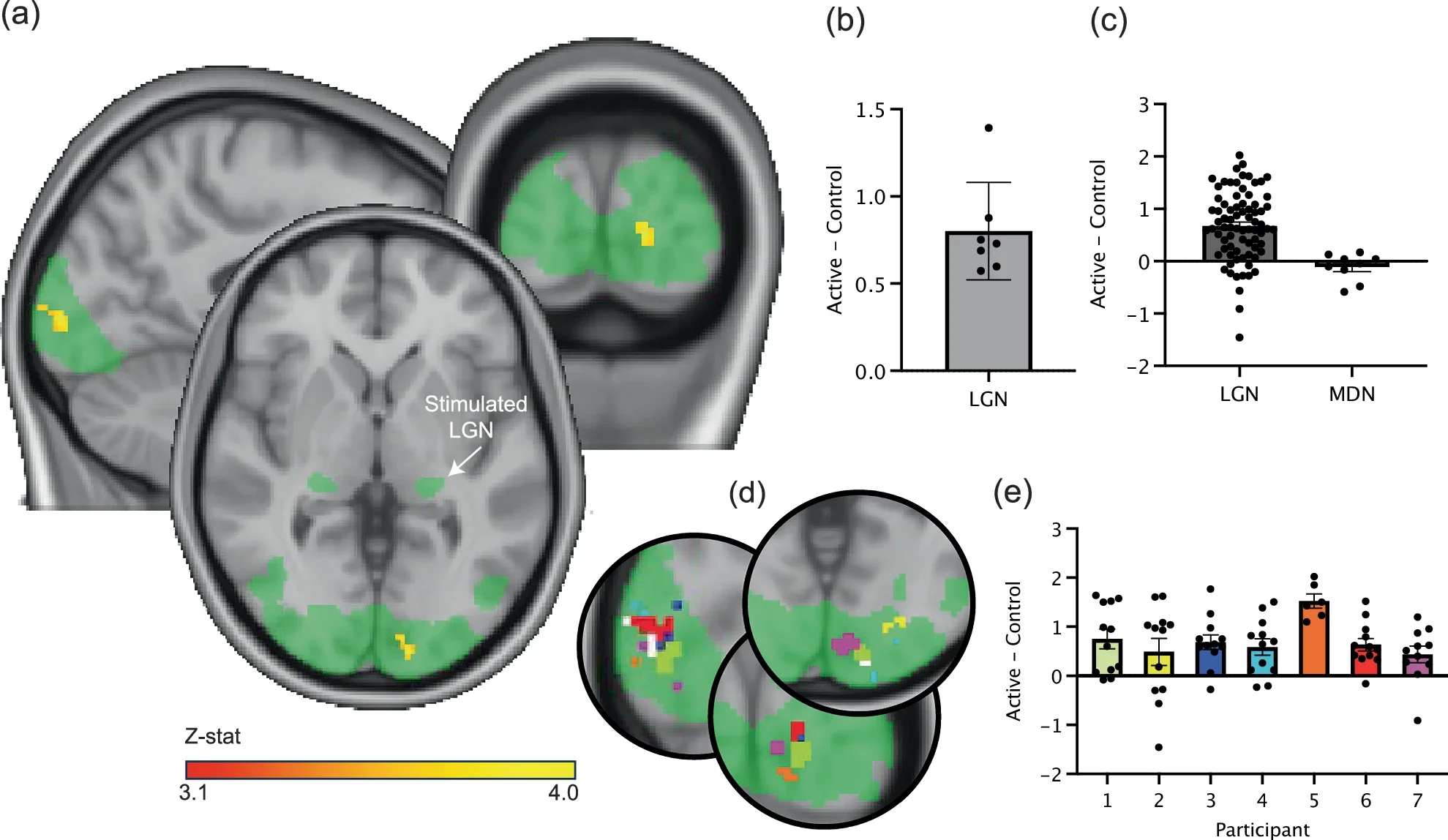

To show the system’s precision, researchers tested it on seven healthy volunteers. They targeted a tiny structure in the center of the brain called the lateral geniculate nucleus, or LGN. This area sits within the thalamus and plays a key role in visual processing.

Participants viewed a flashing checkerboard on a screen. This visual pattern reliably activates the visual system. When the ultrasound targeted the LGN, brain scans showed a clear rise in activity in the visual cortex, the region at the back of the brain that processes sight.

When the ultrasound was turned on but aimed elsewhere, that increase disappeared. This showed the effect was specific to the LGN. Participants did not report seeing anything different during stimulation, yet their brains clearly responded.

Professor Bradley Treeby of UCL Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering led the study. “This advance opens up opportunities for both neuroscience research and clinical treatment,” he said. “For the first time, scientists can non-invasively study causal relationships in deep brain circuits that were previously only accessible through surgery.”

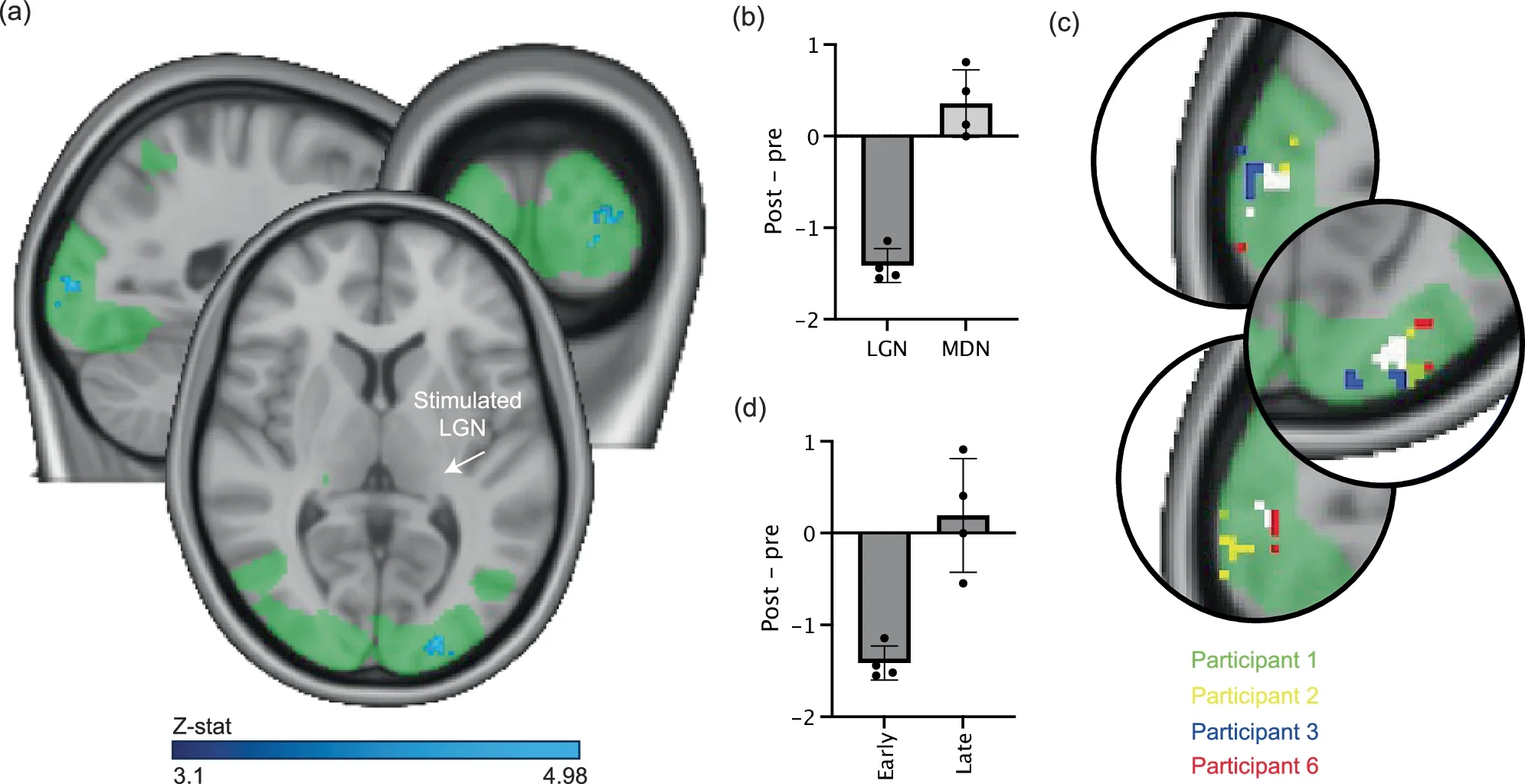

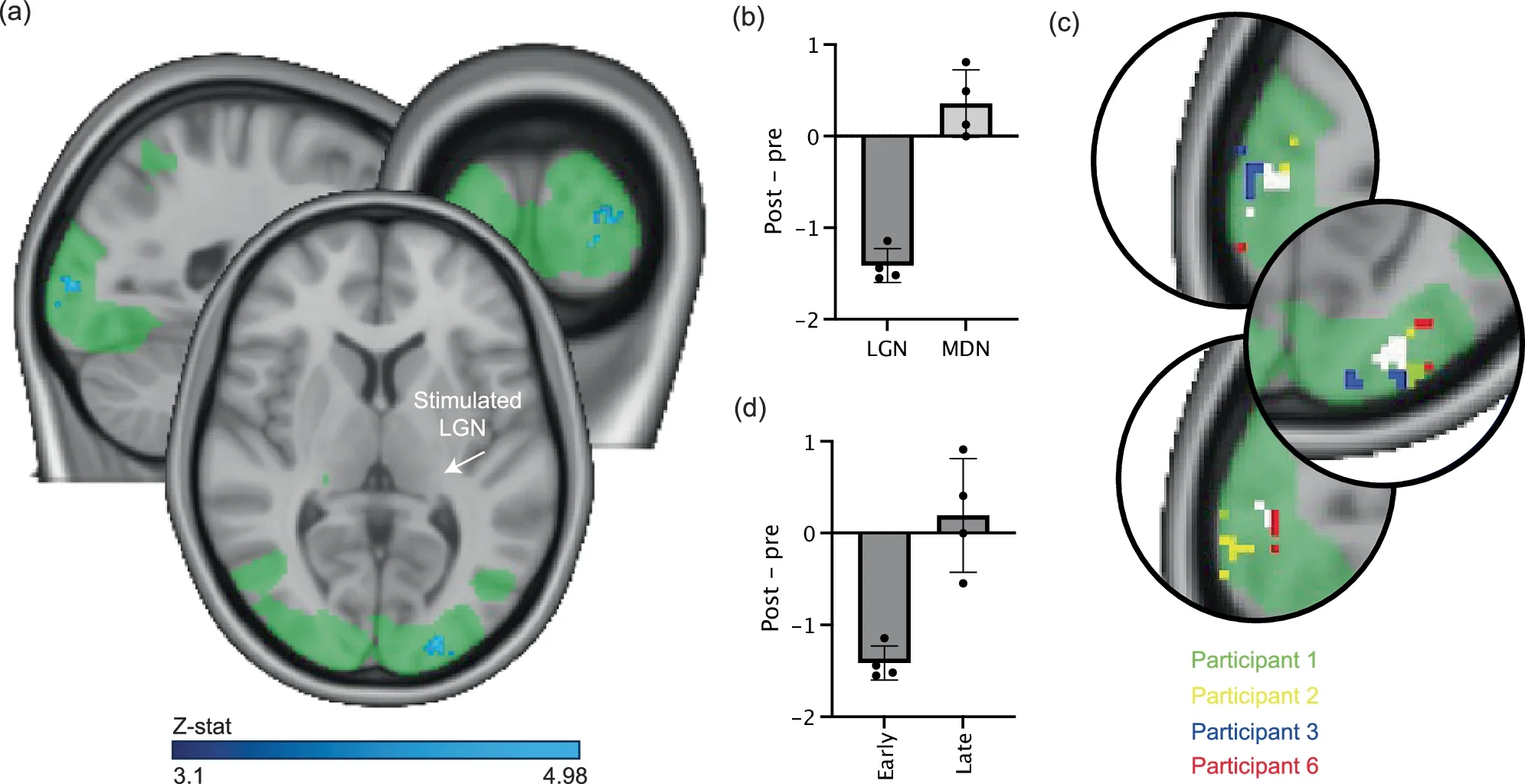

The team also tested whether ultrasound could create longer-lasting changes. They used a patterned stimulation approach and tracked brain activity after the session ended. In several participants, activity in the visual cortex dropped and stayed lower for at least 40 minutes.

That finding matters because lasting effects suggest more than a brief nudge to brain activity. They hint at changes in how networks function over time. When researchers stimulated a nearby control region instead, no such changes appeared. This confirmed the effect depended on precise targeting.

Dr. Eleanor Martin of UCL, the study’s first author, said the system was designed with this goal in mind. “We designed the system to be compatible with simultaneous fMRI, enabling us to monitor the effects of stimulation in real time,” she said. “This opens up exciting possibilities for closed-loop neuromodulation and personalised therapies.”

Many brain disorders involve deep structures. Parkinson’s disease, for example, affects circuits buried far below the brain’s surface. Depression and movement disorders also involve deep networks. Being able to influence those areas without surgery could transform care.

Dr. Ioana Grigoras of the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences highlighted this potential. “This novel brain stimulation device represents a breakthrough in our ability to precisely target deep brain structures that were previously impossible to reach non-invasively,” she said. She added that the team is especially excited about applications for Parkinson’s disease.

Because the method is non-invasive, it could allow doctors to test different targets safely. Clinicians might explore which brain areas respond best before committing to surgical treatment. In some cases, ultrasound could even replace invasive procedures.

The research team is already thinking beyond the lab. Several members have founded NeuroHarmonics, a UCL spinout company. The goal is to develop a portable, wearable version of the system. Such a device could bring precise brain stimulation into clinics and research centers worldwide.

The study was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Wellcome, and the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. While more work is needed to understand exactly how ultrasound changes neural activity, the results mark a major milestone.

They show that deep brain modulation without surgery is no longer a distant hope. It is now a demonstrated reality.

This technology could change how scientists study deep brain circuits, allowing safer and more precise experiments in humans. Clinically, it offers a non-invasive alternative to surgical deep brain stimulation for conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, and essential tremor.

The system could help doctors test treatments, personalize therapy, and reduce surgical risks.

Over time, it may lead to wearable brain stimulation tools that improve quality of life for many patients.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ultrasound helmet reaches deep into the brain without surgery appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

For decades, scientists have searched for a safe way to reach deep parts of the human brain without cutting into the skull. That goal now feels closer. Researchers from University College London and the University of Oxford have developed an ultrasound device that can precisely influence deep brain regions in living people, without surgery. The system opens new paths for studying how the brain works and for treating conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, and essential tremor.

The work centers on a technology called transcranial ultrasound stimulation, or TUS. Unlike electrical or magnetic brain stimulation, ultrasound can travel deeper through the skull. Until now, however, it lacked the precision needed to target specific brain structures. This new system changes that, allowing scientists to focus on areas thousands of times smaller than before.

You rely on deep brain structures every moment, even if you never think about them. These regions help guide movement, shape emotions, and process sensory information. Yet studying them has always been difficult. Many existing tools either require invasive surgery or affect wide areas of the brain at once.

Deep brain stimulation, used for Parkinson’s disease, involves implanting electrodes directly into the brain. While effective, it carries surgical risks. Other non-invasive methods, such as magnetic stimulation, mostly reach the brain’s surface. The challenge has been finding a method that is both non-invasive and precise at depth.

Transcranial ultrasound offered hope because sound waves can pass through bone. Early systems, however, spread their effects too broadly. They influenced large regions instead of precise targets, limiting both research and clinical use.

The new system looks a bit like a helmet. Inside it are 256 small ultrasound elements that work together. Each element emits gentle sound waves. When combined, those waves meet at a precise point deep in the brain. The result is a focused spot of stimulation that is extremely small, about 1,000 times smaller than what conventional ultrasound systems can achieve.

A soft plastic face mask helps keep the head still during use. This improves accuracy by preventing small movements that could shift the target. The team also used detailed computer models of each participant’s skull to guide the ultrasound beams. These models account for skull shape and thickness, which affect how sound travels.

Crucially, the system works alongside functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. This lets researchers watch brain activity change in real time while stimulation occurs. They can see whether the correct area responds, rather than guessing.

To show the system’s precision, researchers tested it on seven healthy volunteers. They targeted a tiny structure in the center of the brain called the lateral geniculate nucleus, or LGN. This area sits within the thalamus and plays a key role in visual processing.

Participants viewed a flashing checkerboard on a screen. This visual pattern reliably activates the visual system. When the ultrasound targeted the LGN, brain scans showed a clear rise in activity in the visual cortex, the region at the back of the brain that processes sight.

When the ultrasound was turned on but aimed elsewhere, that increase disappeared. This showed the effect was specific to the LGN. Participants did not report seeing anything different during stimulation, yet their brains clearly responded.

Professor Bradley Treeby of UCL Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering led the study. “This advance opens up opportunities for both neuroscience research and clinical treatment,” he said. “For the first time, scientists can non-invasively study causal relationships in deep brain circuits that were previously only accessible through surgery.”

The team also tested whether ultrasound could create longer-lasting changes. They used a patterned stimulation approach and tracked brain activity after the session ended. In several participants, activity in the visual cortex dropped and stayed lower for at least 40 minutes.

That finding matters because lasting effects suggest more than a brief nudge to brain activity. They hint at changes in how networks function over time. When researchers stimulated a nearby control region instead, no such changes appeared. This confirmed the effect depended on precise targeting.

Dr. Eleanor Martin of UCL, the study’s first author, said the system was designed with this goal in mind. “We designed the system to be compatible with simultaneous fMRI, enabling us to monitor the effects of stimulation in real time,” she said. “This opens up exciting possibilities for closed-loop neuromodulation and personalised therapies.”

Many brain disorders involve deep structures. Parkinson’s disease, for example, affects circuits buried far below the brain’s surface. Depression and movement disorders also involve deep networks. Being able to influence those areas without surgery could transform care.

Dr. Ioana Grigoras of the University of Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences highlighted this potential. “This novel brain stimulation device represents a breakthrough in our ability to precisely target deep brain structures that were previously impossible to reach non-invasively,” she said. She added that the team is especially excited about applications for Parkinson’s disease.

Because the method is non-invasive, it could allow doctors to test different targets safely. Clinicians might explore which brain areas respond best before committing to surgical treatment. In some cases, ultrasound could even replace invasive procedures.

The research team is already thinking beyond the lab. Several members have founded NeuroHarmonics, a UCL spinout company. The goal is to develop a portable, wearable version of the system. Such a device could bring precise brain stimulation into clinics and research centers worldwide.

The study was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Wellcome, and the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. While more work is needed to understand exactly how ultrasound changes neural activity, the results mark a major milestone.

They show that deep brain modulation without surgery is no longer a distant hope. It is now a demonstrated reality.

This technology could change how scientists study deep brain circuits, allowing safer and more precise experiments in humans. Clinically, it offers a non-invasive alternative to surgical deep brain stimulation for conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, depression, and essential tremor.

The system could help doctors test treatments, personalize therapy, and reduce surgical risks.

Over time, it may lead to wearable brain stimulation tools that improve quality of life for many patients.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Ultrasound helmet reaches deep into the brain without surgery appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.