Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany and the Centro de Astrobiología, part of Spain’s CSIC-INTA, have identified the largest sulfur-bearing molecule ever confirmed in interstellar space. The discovery fills a long-standing gap in astrochemistry and strengthens the link between space chemistry and the origins of life.

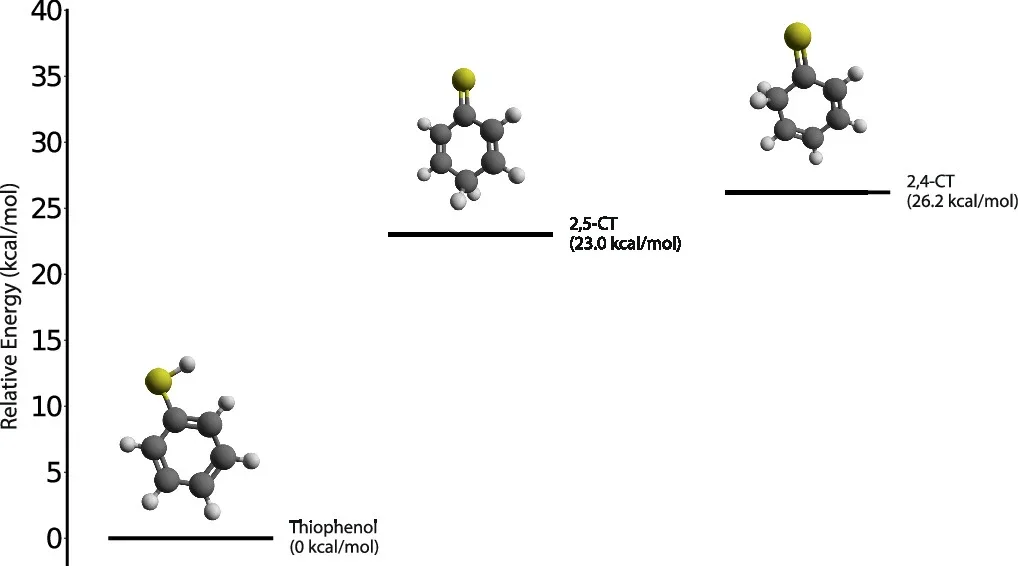

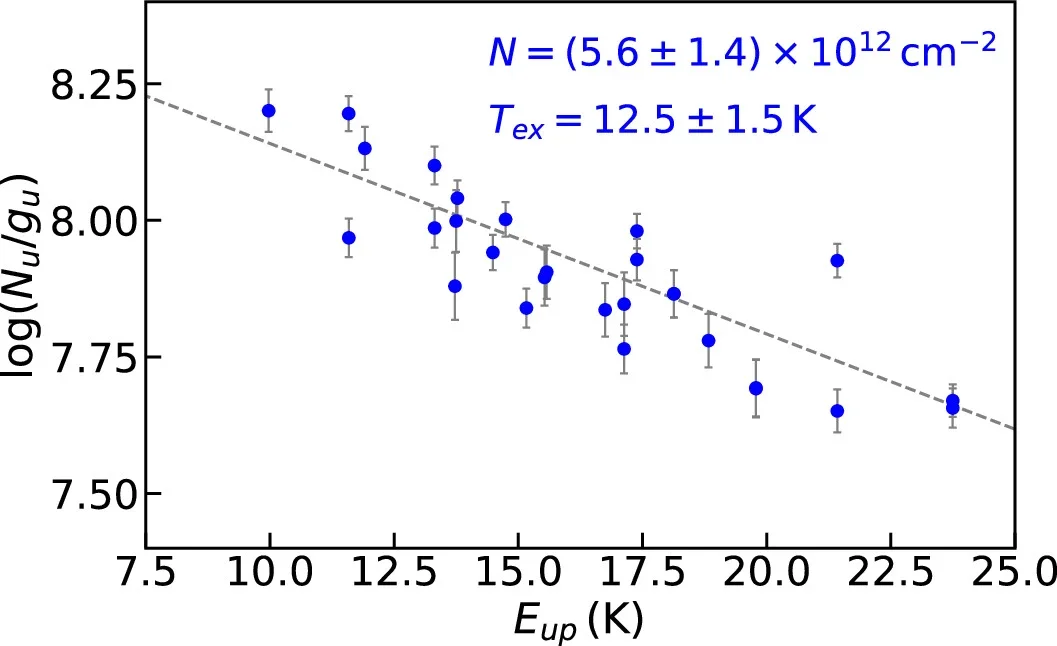

The molecule, called 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-thione, has 13 atoms arranged in a stable six-membered ring. It was detected inside a dense molecular cloud near the center of the Milky Way, about 27,000 light-years from Earth. Until now, sulfur compounds found in space were much smaller, usually fewer than six atoms.

“This is the first unambiguous detection of a complex, ring-shaped sulfur-containing molecule in interstellar space and a crucial step toward understanding the chemical link between space and the building blocks of life,” said Mitsunori Araki, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute and lead author of the study.

The cloud, known as G+0.693-0.027, sits near the Galactic Center and has become a hotspot for complex molecule discoveries. It contains no stars, yet it shows surprisingly rich chemistry. That makes it an ideal place to study how complex molecules form before stars and planets exist.

Sulfur is essential for life on Earth. It plays a key role in proteins, enzymes, and metabolism. Yet in space, sulfur has long behaved strangely. Astronomers detect far less sulfur in gas clouds than expected from cosmic abundance estimates.

That shortfall suggests sulfur may be locked away in forms that are hard to observe. One idea is that it hides inside large, complex molecules or inside dust grains. Meteorites support this view. They contain many large sulfur-bearing ring molecules, including benzothiophene and dibenzothiophene.

The problem has been proof. Those large sulfur rings appeared in meteorites but not in space. Scientists did not know whether they formed later inside asteroids or already existed in interstellar clouds.

The detection of 2,5-cyclohexadiene-1-thione helps close that gap. Its structure resembles sulfur-bearing molecules found in extraterrestrial rocks. That similarity suggests some sulfur chemistry begins long before planets form.

“Our results show that a 13-atom molecule structurally similar to those in comets already exists in a young, starless molecular cloud,” said Valerio Lattanzi, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute. “This proves that the chemical groundwork for life begins long before stars form.”

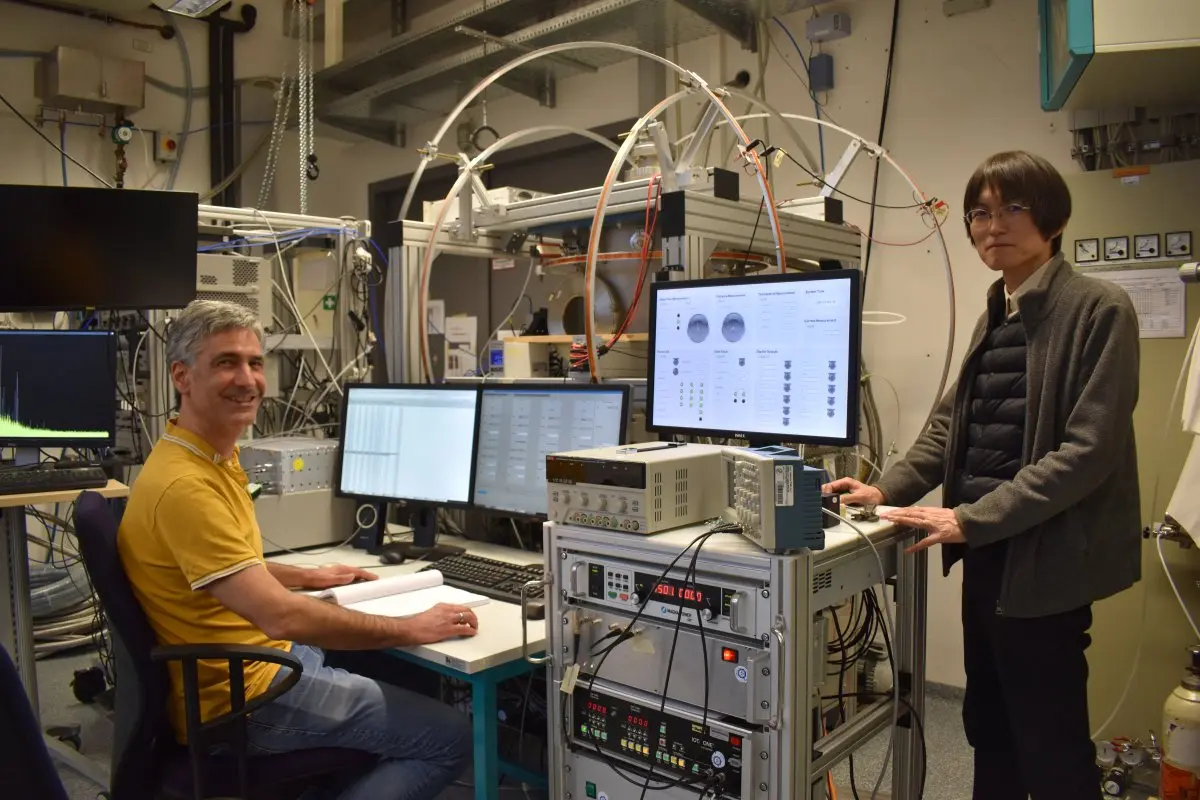

The discovery relied on detailed laboratory work. The research team first created the molecule on Earth using an electrical discharge applied to thiophenol, a sulfur-bearing liquid with a strong odor. The process used a voltage of about 1,000 volts.

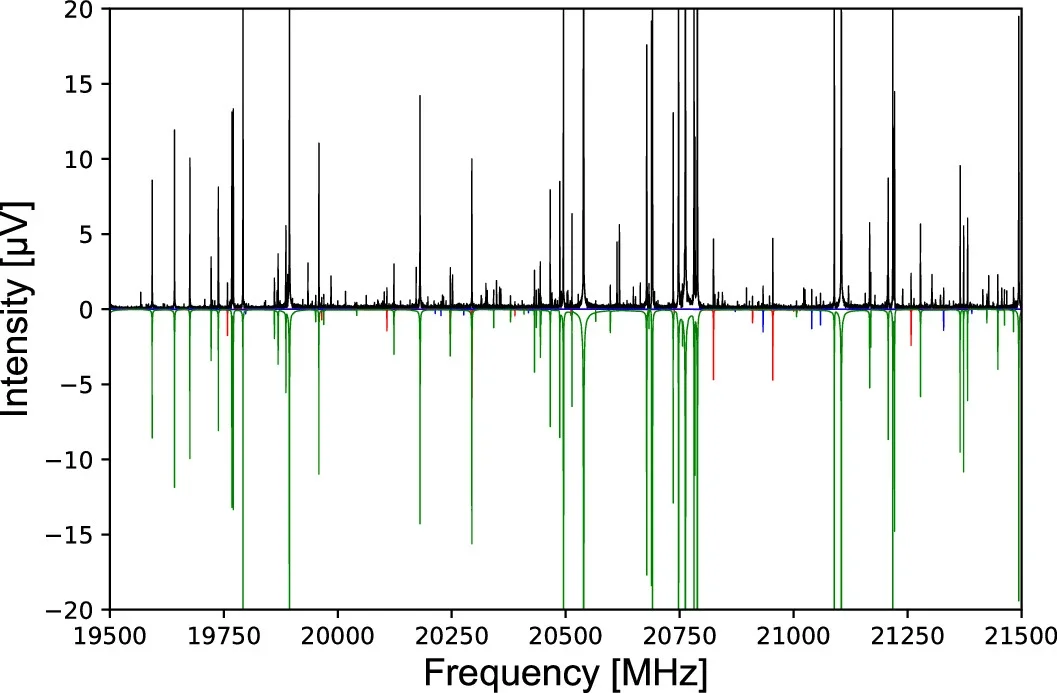

“Using a custom-built spectrometer, our team measured the molecule’s radio emission with extreme precision. That produced a unique spectral fingerprint, accurate to more than seven significant digits,” Lattanzi shared with The Brighter Side of News.

“We then searched for that fingerprint in astronomical data from a large molecular survey. The observations came from two radio telescopes in Spain, the IRAM 30-meter telescope and the Yebes 40-meter telescope, both operated with support from Spanish institutions,” he added.

“The match was clear. Multiple emission lines appeared at the expected frequencies, all consistent with the same physical conditions inside the cloud,” he concluded.

G+0.693 is chemically rich, with more than 140 known molecules already identified. Many are complex organic compounds with six or more atoms. Shocks caused by cloud collisions likely play a role. Those shocks can knock molecules off icy dust grains and release trapped sulfur.

The detected sulfur ring makes up only a small fraction of the cloud’s total sulfur. Still, its presence shows that sulfur can enter large, stable ring structures in space. That finding challenges earlier assumptions that such chemistry required planets or asteroids.

The researchers also searched for related molecules, including a closely related isomer and thiophenol itself. Neither was clearly detected. That result suggests the newly found molecule may form more efficiently under interstellar conditions.

The exact formation pathway remains uncertain. One possibility involves chemistry on icy dust grains. Experiments show that cosmic rays striking frozen acetylene can produce benzene. A similar process could occur with small sulfur chains already known to exist in the cloud.

Another possibility involves reactions after benzene is released into the gas. In that case, sulfur-bearing radicals could attach and rearrange into ring structures. More lab and theoretical work will be needed to test these ideas.

The study also raises a caution for scientists studying meteorites. The newly detected molecule has the same mass as thiophenol. That means earlier measurements may have confused the two.

This discovery reshapes how you understand sulfur chemistry in space. It shows that complex sulfur-bearing rings can form before stars and planets exist. That insight helps explain why meteorites contain such molecules.

The findings also guide future telescope searches. With accurate laboratory fingerprints now available, astronomers can look for similar molecules elsewhere. That could reveal a hidden population of sulfur compounds.

Beyond astronomy, the work affects studies of life’s origins. Sulfur is central to biology. Knowing it enters complex structures early strengthens the idea that life’s ingredients formed in space and arrived on young planets later.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Largest sulfur-bearing molecule ever found in space links interstellar chemistry to life appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.