Life runs on instructions you never see. Every cell reads DNA, turns that message into RNA, and then builds proteins that keep you alive. That translation system feels so basic that it is easy to forget it had to begin somewhere. Scientists have long debated how the genetic code took shape, and why it settled into the rules we still share with nearly all living things.

A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign argues that part of the answer may be hiding in a surprisingly small place: pairs of amino acids that sit side by side in proteins. These pairs, called dipeptides, appear to carry an ancient signal about how the genetic code emerged and expanded over time. The research links dipeptide patterns to earlier work on transfer RNA and protein building blocks, suggesting the three lines of evidence tell the same evolutionary story.

“We find the origin of the genetic code mysteriously linked to the dipeptide composition of a proteome, the collective of proteins in an organism,” said corresponding author Gustavo Caetano-Anollés, a professor in the Department of Crop Sciences, the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, and Biomedical and Translation Sciences of Carle Illinois College of Medicine.

The findings offer a new way to think about one of biology’s oldest puzzles. They also point toward practical payoffs for fields that try to rewrite life’s instructions, including genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and bioinformatics.

The genetic code is often described as a translation table. It connects nucleic acids, like DNA and RNA, to amino acids, the ingredients of proteins. In daily life, you might think of it like matching words to meaning. In a cell, the match has to be precise, because proteins only work if their amino acids arrive in the right order.

Caetano-Anollés argues that life is powered by two linked “languages.” One language stores instructions in nucleic acids. The other language is written in proteins, which carry out most of the actual work inside cells. Bridging these languages is the ribosome, the cell’s protein factory, which stitches amino acids into long chains. Transfer RNA, or tRNA, brings amino acids to the ribosome, one at a time. Enzymes called aminoacyl tRNA synthetases load the right amino acid onto each tRNA. The study describes these enzymes as guardians that help keep the system accurate.

“Why does life rely on two languages; one for genes and one for proteins?” Caetano-Anollés asked. “We still don’t know why this dual system exists or what drives the connection between the two. The drivers couldn’t be in RNA, which is functionally clumsy. Proteins, on the other hand, are experts in operating the sophisticated molecular machinery of the cell.”

That question matters because it reaches back to the earliest stages of life. If the genetic code did not appear fully formed, what came first? And what pushed the system toward the rules life uses today?

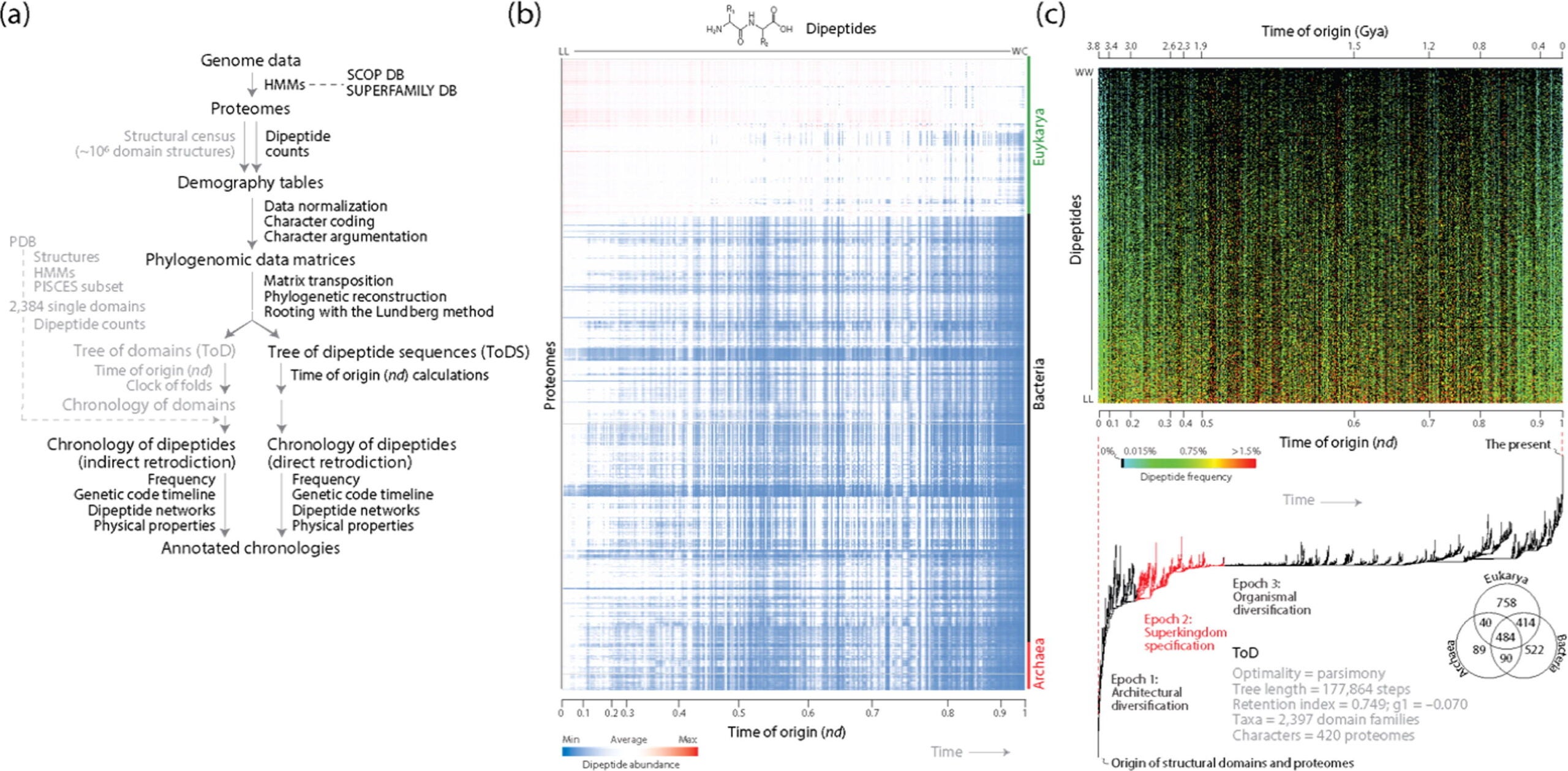

The new work builds on the team’s long focus on phylogenomics, the study of evolutionary relationships across genomes. In earlier research, Caetano-Anollés and colleagues built evolutionary trees for protein domains and for tRNA. Protein domains are structural units that help proteins fold and function. Their past trees helped estimate when different protein parts and tRNA features appeared during evolution.

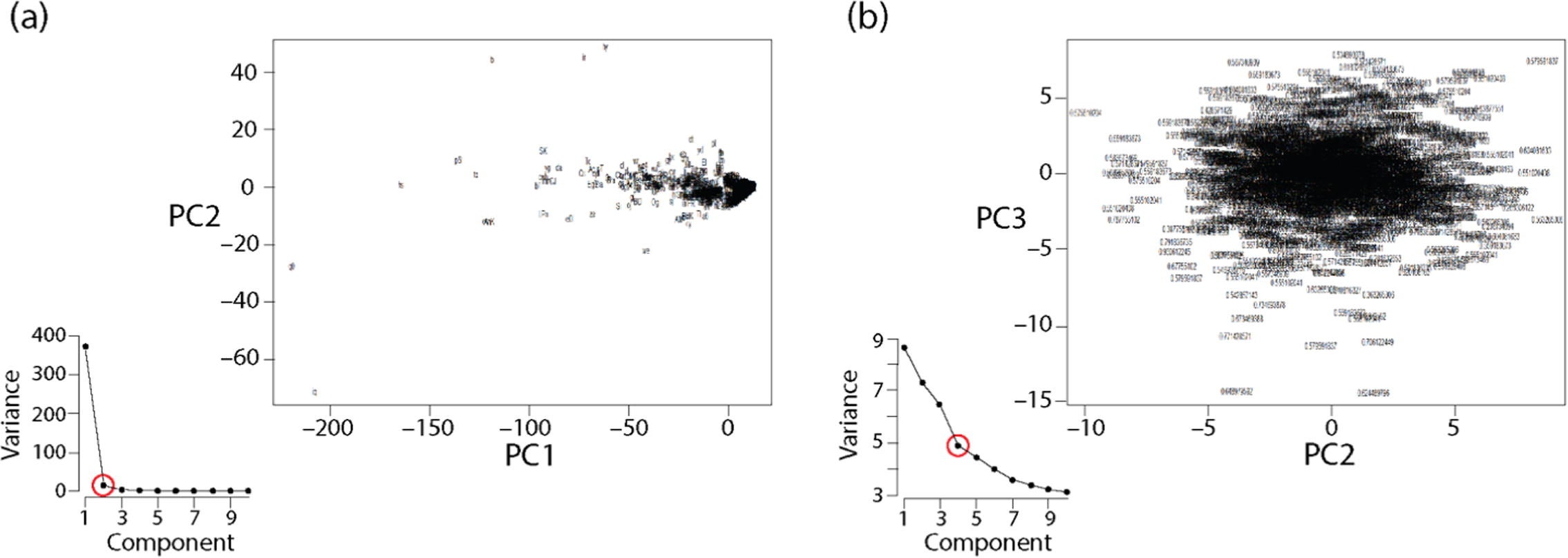

“In this new study, our team asked whether dipeptides could hold a similar timeline. A dipeptide is simply two amino acids linked by a peptide bond. In today’s proteins, dipeptides are everywhere. They shape how proteins bend, fold, and interact. There are 20 common amino acids in life, so there are 400 possible dipeptide combinations. Different organisms show different patterns in how often each pair appears,” Caetano-Anollés told The Brighter Side of News.

“To probe that signal, we analyzed 4.3 billion dipeptide sequences across 1,561 proteomes from the three superkingdoms of life: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. Using that massive dataset, our team built a phylogenetic tree and a chronology of dipeptide evolution. Then we compared it with evolutionary patterns already mapped in protein domains and tRNA. We found alignment across all three,” he added.

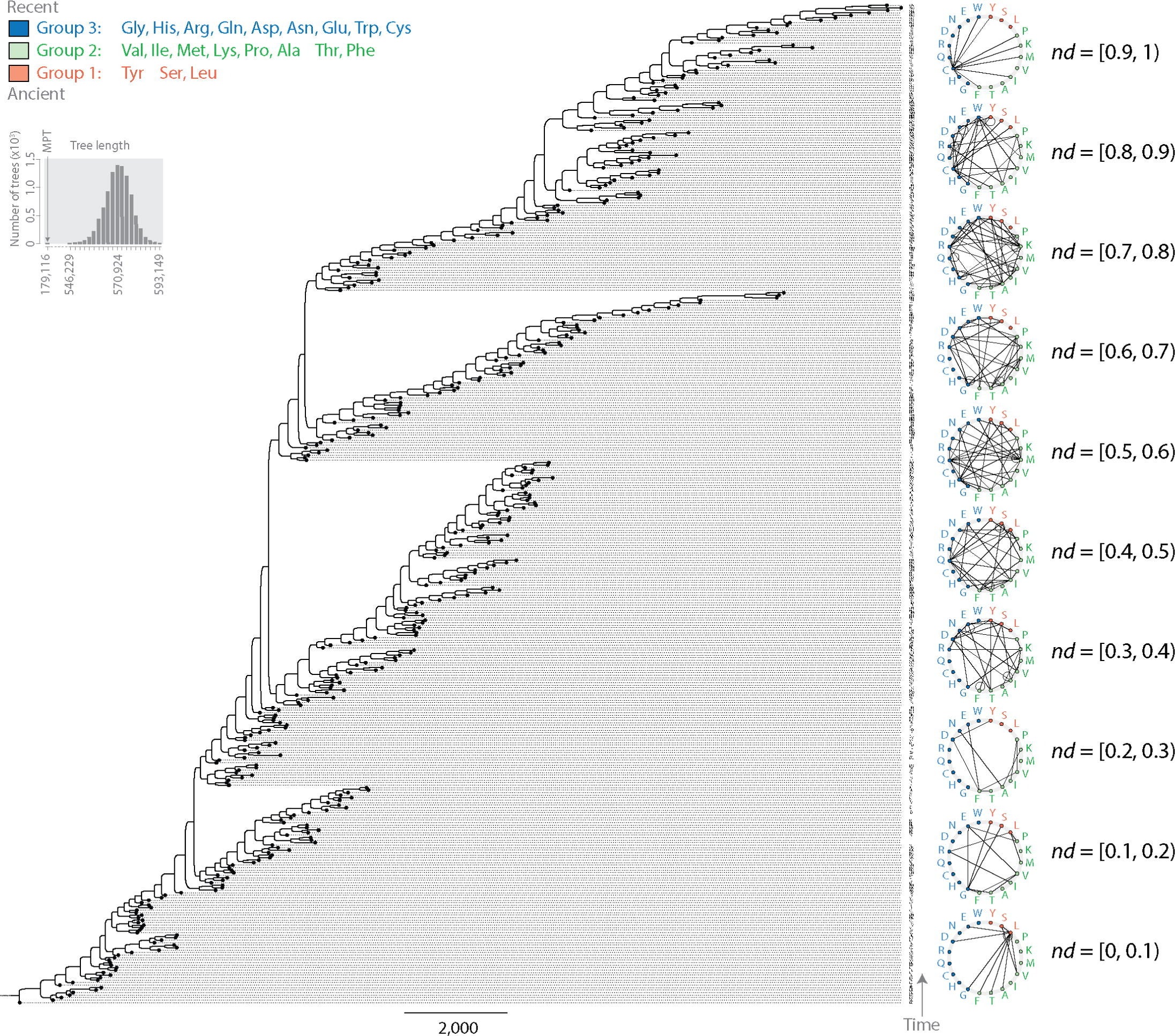

“We found the results were congruent,” Caetano-Anollés explained. “Congruence is a key concept in phylogenetic analysis. It means that a statement of evolution obtained with one type of data is confirmed by another. In this case, we examined three sources of information: protein domains, tRNAs, and dipeptide sequences. All three reveal the same progression of amino acids being added to the genetic code in a specific order.”

That consistency matters because it suggests dipeptides are not random leftovers in proteins. Instead, their history may reflect early rules that shaped how amino acids entered the genetic code.

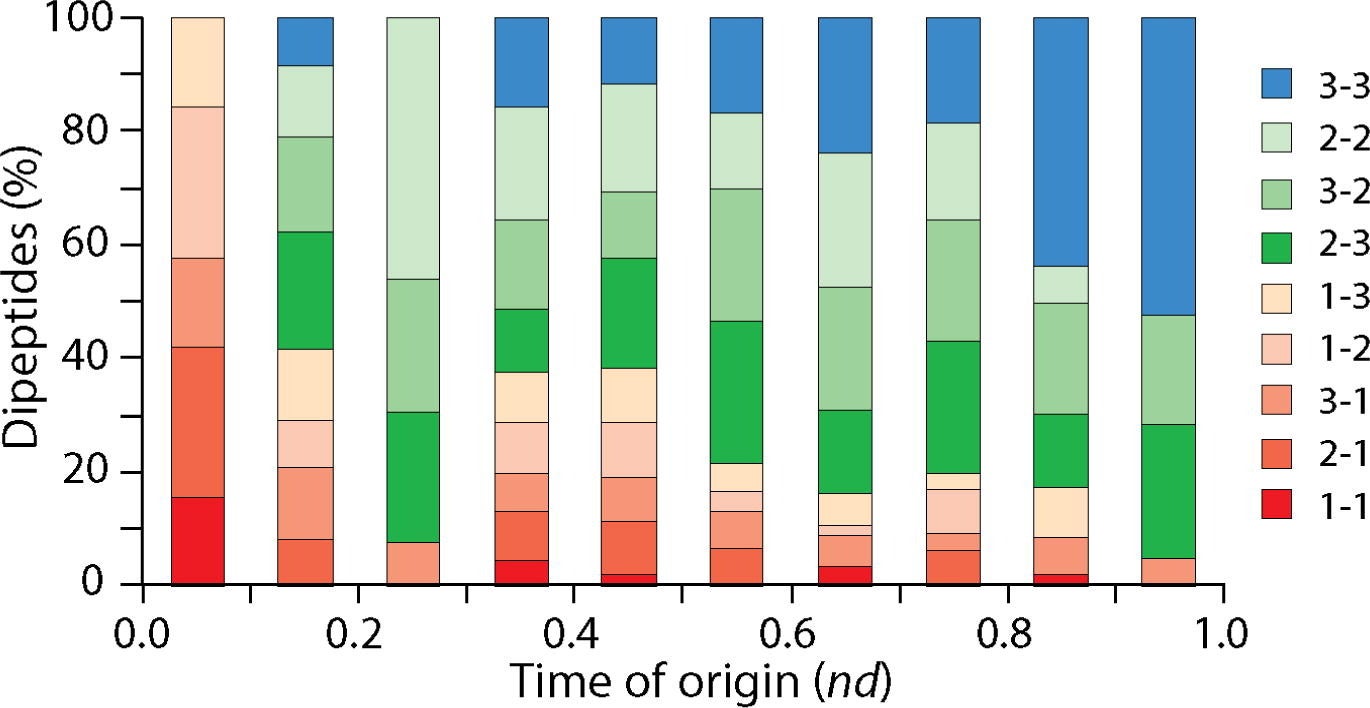

The study ties dipeptide patterns to an earlier timeline the team built from tRNA evolution. That prior work grouped amino acids based on when they appeared in the genetic code. The oldest set, called Group 1, included tyrosine, serine, and leucine. Group 2 added eight more amino acids. These early groups lined up with the rise of “editing” in synthetase enzymes, a quality-control step that corrects misloaded amino acids. They also lined up with an early operational code that helped enforce specificity, meaning a codon points to a single amino acid.

Group 3 included amino acids that appeared later, and the study links them to more derived functions tied to the modern standard genetic code.

In plain terms, the results support an expanding-code view of early life. The code began with a smaller set of amino acids, and it grew in a consistent order as molecular accuracy and complexity improved.

The study places this in a larger timeline of life’s start. Life began about 3.8 billion years ago, the authors note, but genes and the genetic code did not emerge until roughly 800 million years later. Scientists disagree about what drove that transition. Some argue RNA-based catalysts came first. Others argue proteins gained functional roles early and shaped the system. Caetano-Anollés and colleagues have supported the protein-first side, and the dipeptide findings add another line of evidence.

One of the study’s most striking observations involves pairs of dipeptides that mirror each other. If one dipeptide is alanine-leucine, written as AL, then leucine-alanine, LA, is its anti-dipeptide. They contain the same amino acids in reverse order.

The team expected some relationship between these pairs, but they did not expect what they found in the evolutionary tree. Many dipeptide and anti-dipeptide pairs appeared close together on the timeline.

“We found something remarkable in the phylogenetic tree,” Caetano-Anollés said. “Most dipeptide and anti-dipeptide pairs appeared very close to each other on the evolutionary timeline. This synchronicity was unanticipated. The duality reveals something fundamental about the genetic code with potentially transformative implications for biology. It suggests dipeptides were arising encoded in complementary strands of nucleic acid genomes, likely minimalistic tRNAs that interacted with primordial synthetase enzymes.”

That idea paints an image of early life that feels lean and improvised. Complementary strands could have supported paired coding patterns, while small tRNA-like molecules and early enzyme systems tightened control over time. It suggests dipeptides may have served as early structural modules, shaping protein folding demands while the genetic code matured.

The study’s central claim is that dipeptide patterns, tRNA evolution, and protein domain history all point to the same sequence in how amino acids entered the genetic code. That clearer timeline can help researchers who try to reprogram biology. When you understand which parts of the code are most ancient and entrenched, you can better predict what changes will break a system, and what changes might hold.

The work also gives bioinformatics researchers a new signal to track. Dipeptide composition spans whole proteomes, so it can serve as a broad fingerprint of evolutionary constraints. That can improve models that infer function from sequence, or tools that compare organisms across deep time.

For synthetic biology, the authors argue that an evolutionary lens can make engineering more realistic. “Synthetic biology is recognizing the value of an evolutionary perspective. It strengthens genetic engineering by letting nature guide the design. Understanding the antiquity of biological components and processes is important because it highlights their resilience and resistance to change.

To make meaningful modifications, it is essential to understand the constraints and underlying logic of the genetic code,” Caetano-Anollés said. In practice, that means better guardrails for designing new biological parts, and fewer surprises when engineered systems behave unpredictably.

Research findings are available online in the Journal of Molecular Biology.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Tiny protein pair discovery could reveal how the genetic code first began appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.