Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, TU Berlin, and the University of Eastern Finland set out to answer a basic question about human behavior: how do people decide where to search and when to move on when resources are uncertain and others are competing for the same prize?

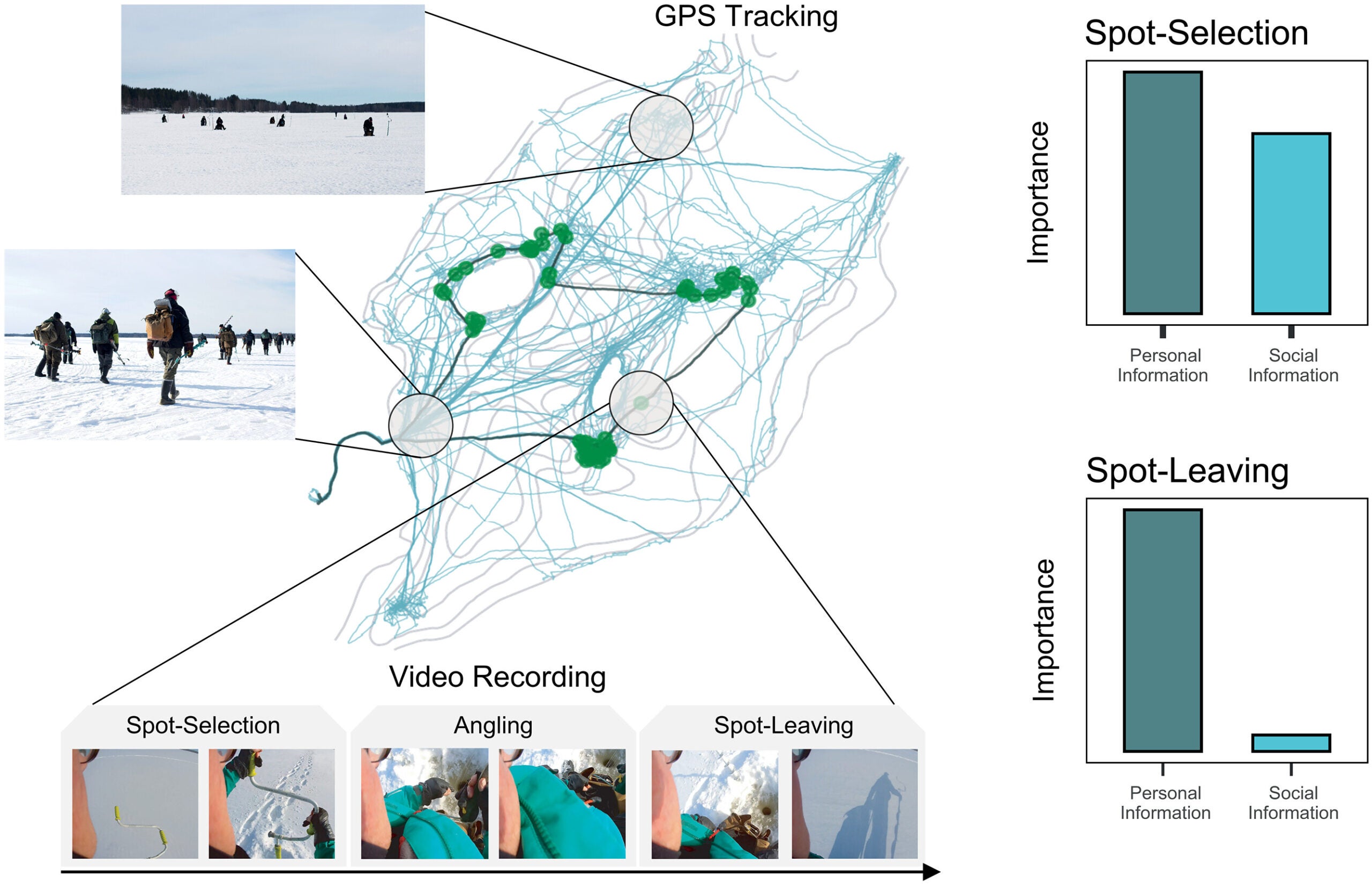

To find out, the international team left the laboratory and followed experienced ice fishers during real competitions in eastern Finland. By combining GPS tracking, wearable cameras, and computer modeling, the scientists captured thousands of real-time decisions made under pressure. The result is one of the most detailed field studies to date on how personal experience and social cues guide human choices.

The study tracked 74 seasoned ice fishers across ten three-hour competitions held on frozen lakes over two winters. Each participant wore a GPS smartwatch and a head-mounted camera, allowing researchers to reconstruct movements and actions second by second. Across 477 fishing trips, the team recorded more than 16,000 decisions about where to drill, how long to fish, and when to leave.

“We wanted to get out of the lab,” said Alexander Schakowski, first author of the study and a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Adaptive Rationality at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development. “Most cognitive research struggles to capture large social settings in the real world.”

Ice fishing competitions offered a rare mix of realism and control. Everyone started at the same time, fished for three hours, and competed for the highest catch weight. Fish were mobile, weather conditions were harsh, and competitors constantly influenced one another’s choices.

Participants were highly experienced, averaging more than four decades of fishing. Women made up just over 23 percent of the group, and the average age was 61. During a single competition, anglers walked more than a kilometer on average and drilled over 30 fishing holes.

The lakes themselves varied widely in productivity. Some yielded frequent catches, while others tested patience. These differences allowed researchers to see how strategies shifted depending on environmental conditions.

By reviewing video footage and GPS tracks together, the team identified two recurring decisions that shaped success: where to go next and when to give up on a spot.

To understand how anglers chose their next location, researchers built computational models inspired by animal movement studies. Each real movement was compared with dozens of simulated alternatives to determine which factors mattered most.

Three types of information guided choices. Personal experience came from past successes and failures. Social information came from watching where other fishers gathered. Ecological information came from lake features such as depth changes.

The strongest influences were personal and social cues. Anglers were more likely to fish near spots where they had previously caught fish and near clusters of other participants. They actively avoided areas linked to past failures.

“Whether people rely more on others or on themselves depends to some degree on their own success,” Schakowski said. Successful anglers trusted their own experience. Those struggling without catches increasingly followed others.

Environmental features played a smaller role. Although many fishers believe lakebed structure signals good habitat, those cues did not reliably predict success during the competitions.

Patterns shifted sharply after a catch. When someone caught a fish, their next moves became tighter and more local. They searched nearby areas more intensely, a behavior known as area-restricted search. This effect grew stronger in crowded areas.

After repeated failures, movement changed. Anglers walked farther, moved more directly, and abandoned spots more quickly. Even one successful catch could reverse that pattern.

Social context amplified these shifts. High local density made people more likely to stay and search carefully after success. Watching others succeed appeared to reinforce confidence in a location.

“These behaviors look strikingly similar to patterns seen in animals,” said Ralf Kurvers, senior research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and principal investigator at TU Berlin’s Cluster of Excellence “Science of Intelligence.”

Deciding when to leave a fishing hole followed simpler rules. The strongest predictor was time without a catch. The longer someone waited without success, the more likely they were to move on.

“Catching the first fish dramatically reduced the chance of leaving. That single success often extended fishing time by several minutes,” Schakowski told The Brighter Side of News.

“Social cues mattered less once fishing began. In crowded areas, anglers stayed slightly longer, but personal experience dominated. Once committed to a hole, people trusted what was happening on their line more than what others nearby were doing,” he continued.

Age and gender also shaped behavior. Women relied more on social information when choosing where to fish. Older participants stayed longer at spots and were less likely to avoid unsuccessful areas. Self-rated skill, however, showed no clear link to strategy.

Lake conditions mattered too. On lakes with fewer fish, anglers searched more locally and waited longer before leaving. Scarcity encouraged patience.

The findings challenge the idea that human search behavior is either individual or social. Instead, people blend both, adjusting their reliance based on recent outcomes.

“Our results not only help us understand human search behavior in complex environments,” said Raine Kortet, professor of aquatic ecology at the University of Eastern Finland, “our method could also be tested in resource and conservation management.”

By pairing high-resolution field data with computational modeling, the study offers a powerful new way to examine decision-making in real social environments, far beyond frozen lakes.

The research provides insight into how crowds form around shared resources and how overuse can emerge. These findings could inform fisheries management, conservation planning, and even crowd control in urban spaces.

Beyond ecology, the approach offers a template for studying human behavior in settings where social influence and uncertainty collide, from financial markets to online platforms.

Understanding when people follow others and when they trust themselves could help design systems that reduce harmful herding and promote smarter collective decisions.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post What ice fishing can teach you about human decision-making appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.