Stanford University researchers have pulled back a curtain on a hidden part of Earth that rarely makes headlines. Their new work maps a strange kind of earthquake that starts deep below the crust, inside the continental mantle. The team says the map could help you understand how earthquakes begin, even the ones that shake your neighborhood.

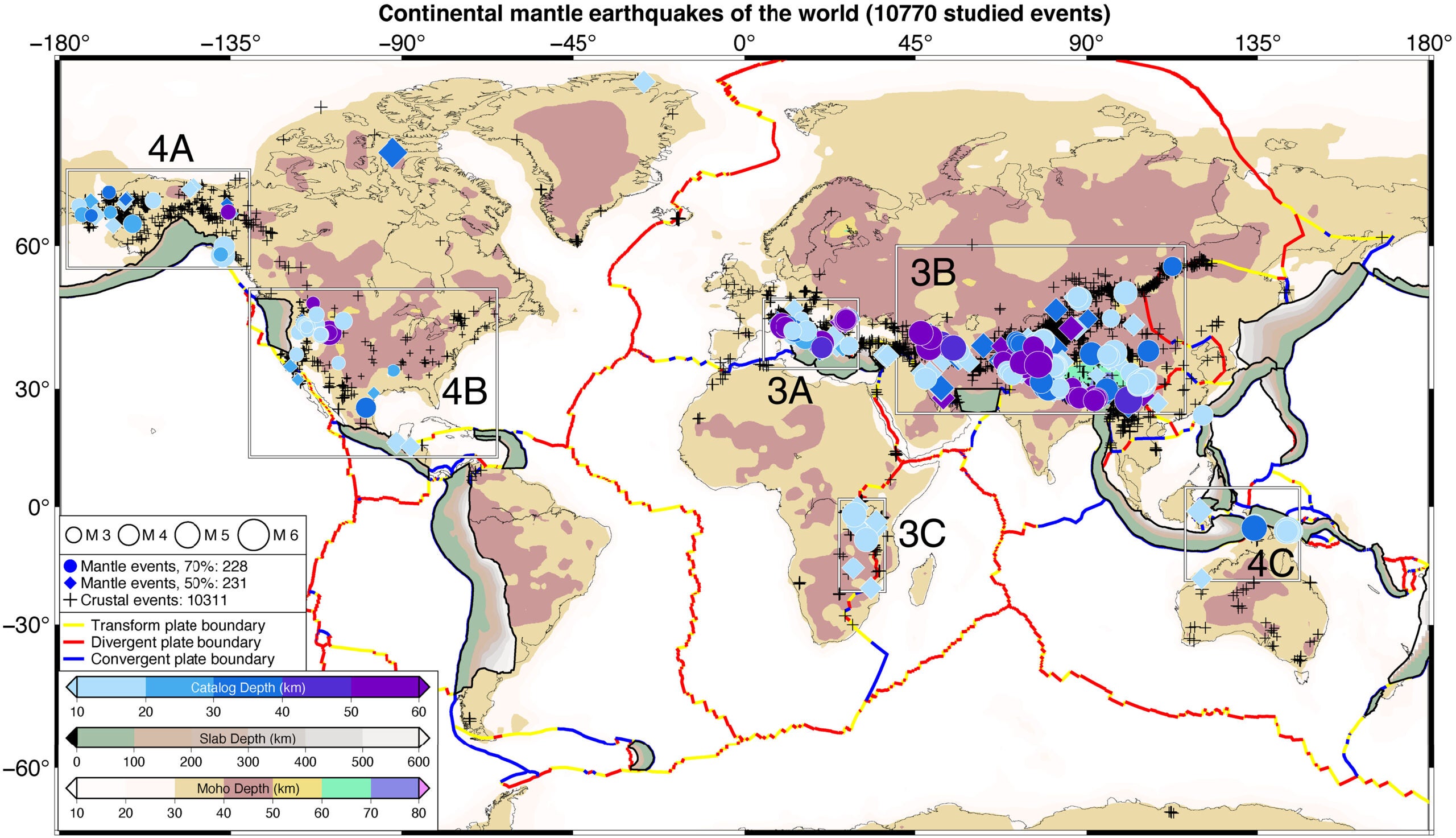

The study, published in Science, comes from Shiqi (Axel) Wang and geophysics professor Simon Klemperer at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. They built what they call the first global map of these rare “continental mantle earthquakes,” events that happen beneath the crust but away from major subduction zones.

“Until this study, we haven’t had a clear global perspective on how many continental mantle earthquakes are really happening and where,” said Wang, a former PhD student in Klemperer’s lab. “With this new dataset, we can start to probe at the various ways these rare mantle earthquakes initiate.”

These quakes are usually too deep to do much at the surface. Still, their odd birthplace may give scientists a cleaner view of what is happening at the boundary between Earth’s crust and mantle.

“Although we know the broad strokes that earthquakes generally happen where stress releases at fault lines, why a given earthquake happens where it does and the main mechanisms behind it are not well grasped,” Klemperer said. “Mantle earthquakes offer a novel way to explore earthquake origins and the internal structure of Earth beyond ordinary crustal earthquakes.”

Earth’s crust is thin and brittle, which makes it easier to crack suddenly in an earthquake. Below it sits the mantle, a warmer, denser layer about 1,800 miles thick. The boundary between them is called the Mohorovičić discontinuity, also known as the “Moho.”

For decades, scientists argued over whether the mantle could produce true earthquakes under continents. Most continental quakes start about 6 to 18 miles down, well above the Moho. Subduction zones are a special case, because diving ocean plates can trigger deep quakes hundreds of miles down. But some measurements have hinted at quake origins beneath continents that sit far below the Moho, even tens of miles under it.

Over the past decade, many researchers have come to accept that these mantle quakes exist, though they seem far rarer than crustal ones. The big problem has been proof. Quake depth estimates can be fuzzy, and you often need a separate local study to know exactly how thick the crust is.

So Wang and Klemperer tried a different approach. Instead of leaning on depth alone, they focused on the “fingerprints” earthquakes leave in seismic waves that race through Earth.

The Stanford team compared two kinds of vibrations recorded by seismometers. One is Sn, a shear wave that travels through the uppermost mantle, sometimes called the mantle “lid.” The other is Lg, a high-frequency wave that moves easily through the crust and tends to bounce around inside it.

Their key test is the ratio between these waves. A strong Sn signal compared with Lg can point to a mantle origin.

“Our approach is a complete game-changer because now you can actually identify a mantle earthquake purely based on the waveforms of earthquakes,” Wang said.

To make the method fair across different regions, they did not use one fixed cutoff. Instead, they compared each candidate quake to nearby quakes recorded on the same stations. That helps control for odd local effects, like pockets of melt in the mantle or scattering in the crust.

The method has limits. You can miss mantle quakes where there are few nearby events to compare against. Even so, it lets researchers search worldwide in a consistent way, rather than debating one quake at a time.

The researchers started with 46,616 earthquakes since 1990 and narrowed them down using quality checks and station coverage. In the end, they identified 459 continental mantle earthquakes.

The map shows these events occur around the world, but they cluster in certain places. Big concentrations show up in and around the Himalayas and across the Bering Strait between Asia and North America, south of the Arctic Circle.

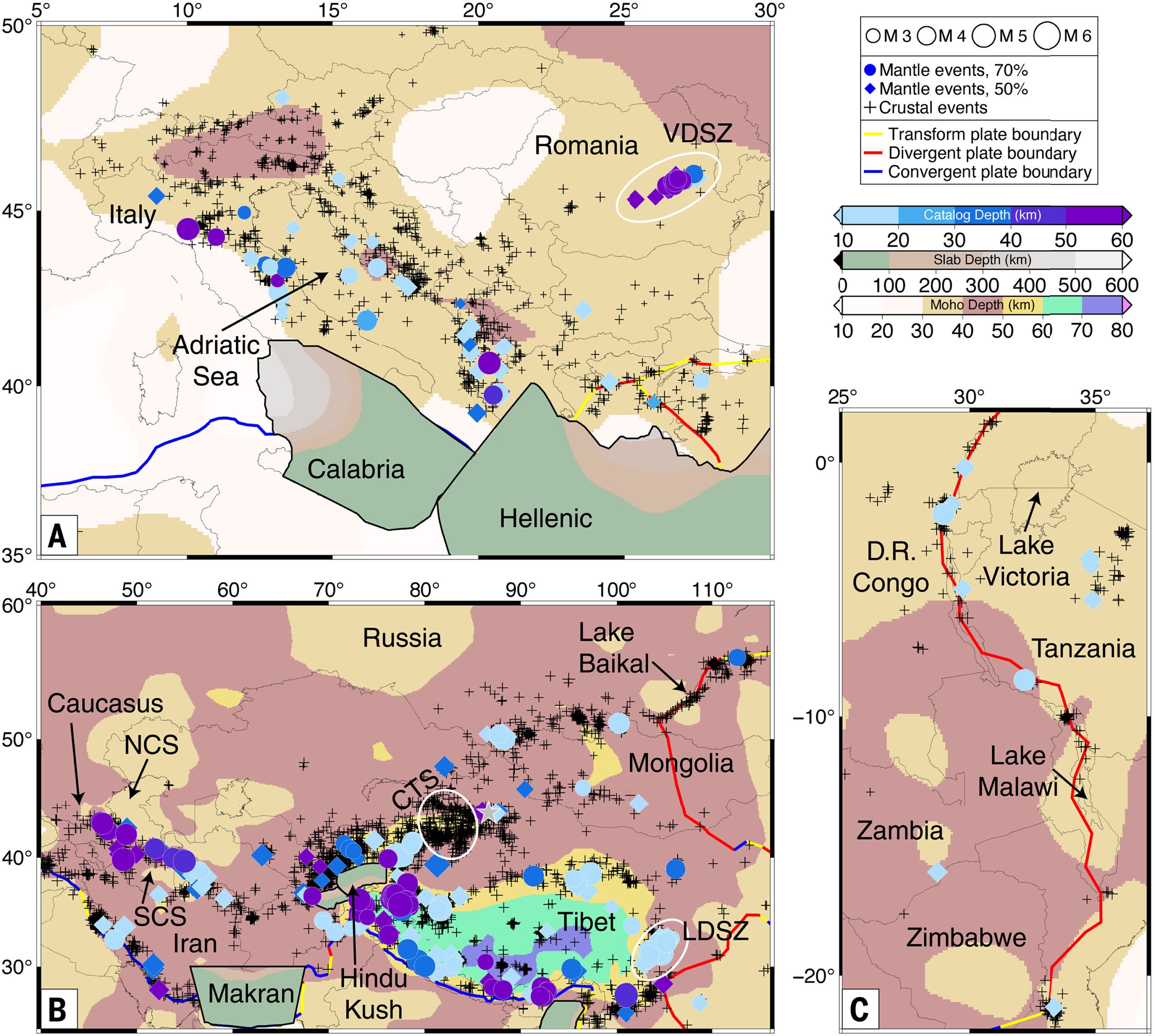

In southern Asia, the pattern around Tibet stands out. The Tibetan Plateau is almost ringed by mantle quakes, while much of its interior has few. Along the plateau’s eastern edge, the team found 72 mantle quakes stretching about 350 kilometers along the Longmenshan fault. Many appear linked to the 2008 magnitude 8.0 Wenchuan earthquake, suggesting some mantle quakes may be triggered by stress changes from major crustal events.

Across Europe and western Asia, the map shows mantle quakes along parts of the Alpine-Himalayan belt. The study also flags activity in Romania’s Vrancea deep seismic zone, and it reports a handful beneath Iran’s Zagros mountains, where earlier searches had not found them.

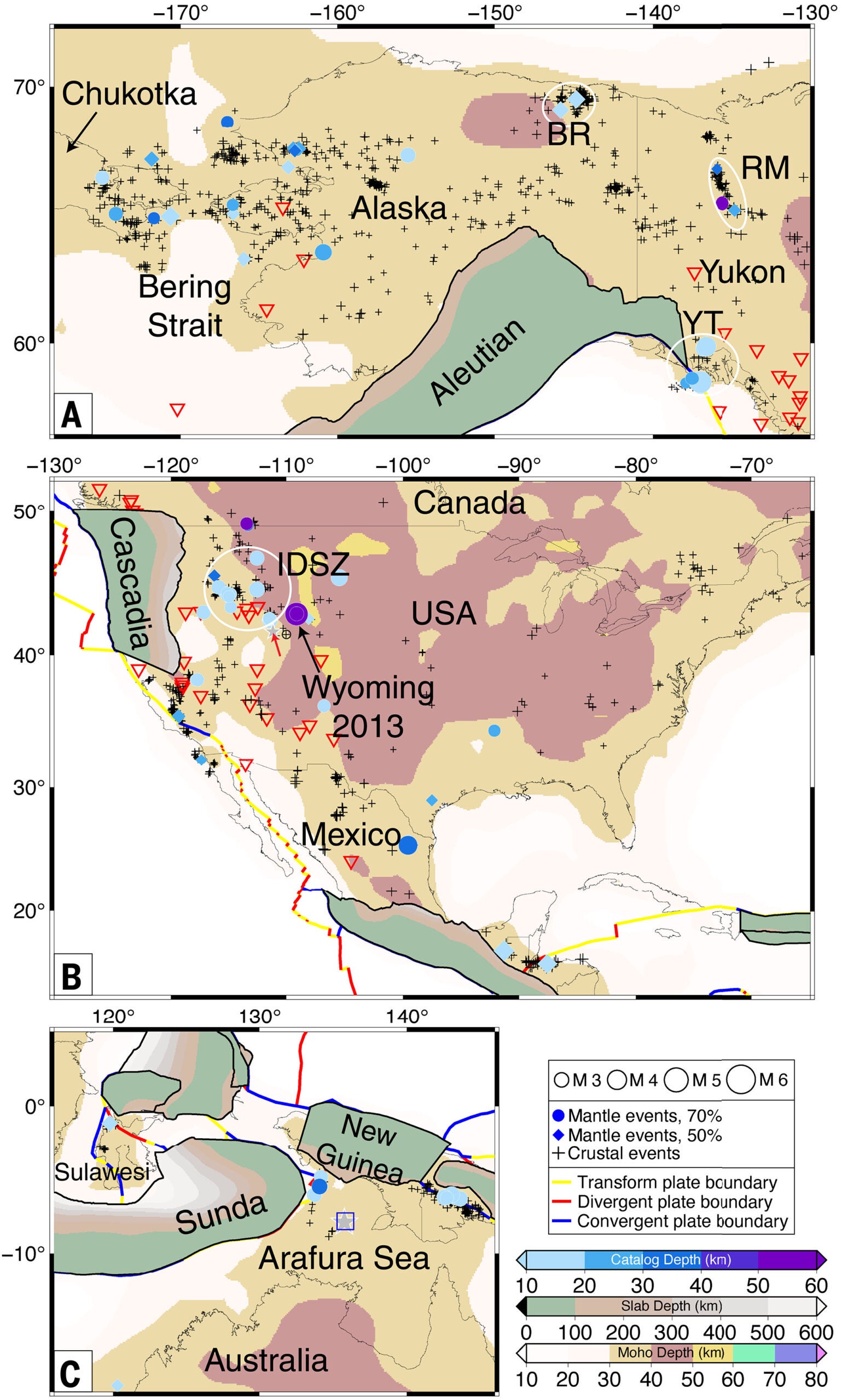

North America looks different partly because seismic networks are dense, which makes detection easier. The team found a productive zone of mantle quakes spanning the Bering Strait in a diffuse plate boundary area. That is surprising because the crust there is thin and the region has recent volcanism, conditions that might seem unfriendly to brittle ruptures deep down.

In the lower 48 states, the study confirms two 2013 Wyoming events as mantle quakes. It also identifies more in the western intermountain region, with southern Idaho emerging as a busy spot. Many of these are not tied to active volcanoes, which points toward tectonic stress rather than magma-driven cracking.

Even with all these clusters, the events remain uncommon. In the earthquakes that met the study’s strict requirements, mantle quakes made up about 4% of the set, though the set leans toward deeper events. Using earthquakes assigned a depth of 10 kilometers as a more random sample, the study finds about 3% are mantle quakes.

This map gives scientists a new way to test how Earth’s crust and mantle interact, especially near the Moho. That matters because many big unknowns in earthquake science involve where stress builds, how it moves, and why ruptures start when they do.

The work may also sharpen models of what is happening beneath mountain belts and plate boundaries. Over time, better models can improve hazard forecasts for the more common shallow earthquakes that damage buildings and roads.

Finally, the wave-based method offers a practical tool for future monitoring. As seismic networks expand, especially in remote regions, researchers can spot more of these deep events and use them to probe Earth’s interior like a natural X-ray.

Research findings are available online in the journal Science.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Scientists create the first global map of rare, deep-mantle earthquakes appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.