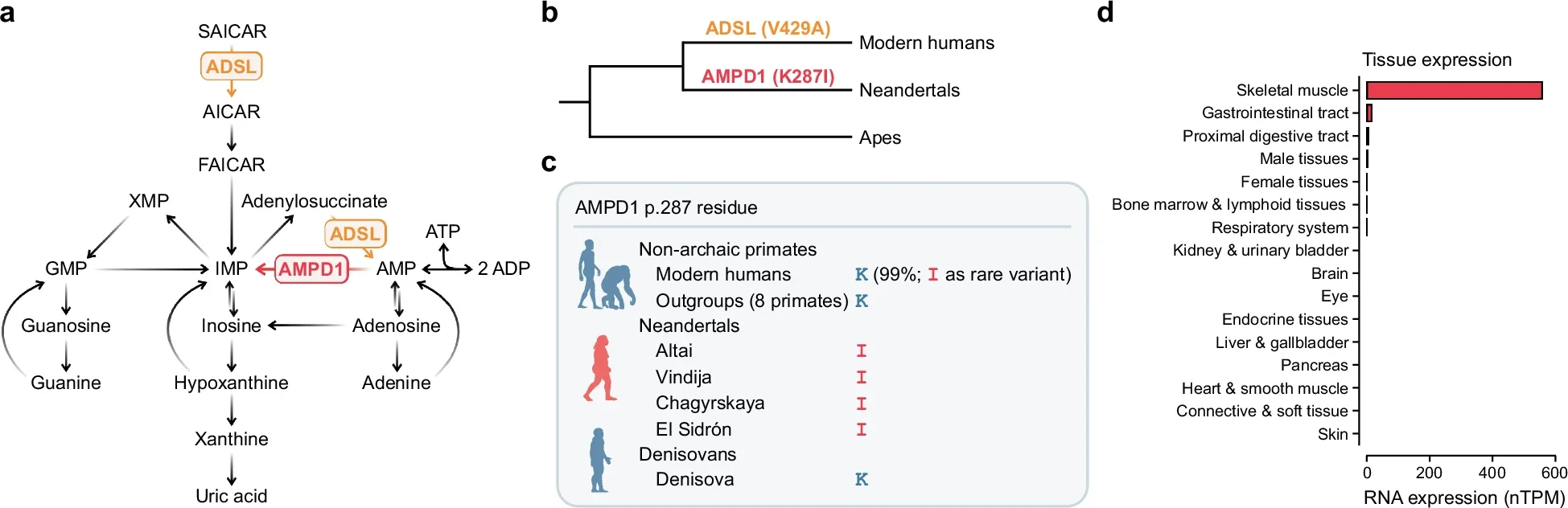

Deep in your muscles, an enzyme called AMPD1 helps turn chemical fuel into usable energy. When it does not work well, muscles tire faster. That matters because problems with AMPD1 are the most common genetic cause of metabolic muscle disease in Europe, affecting up to 14 percent of people.

Now, a new study published in Nature Communications traces one weakened version of this enzyme back tens of thousands of years to Neanderthals. Researchers from Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology compared ancient Neanderthal DNA with modern human genomes and found that every Neanderthal carried the same unusual AMPD1 change. No other primate species had it.

The research team included geneticists who study human evolution and muscle biology. Their work shows how ancient interbreeding still shapes strength, stamina, and health today.

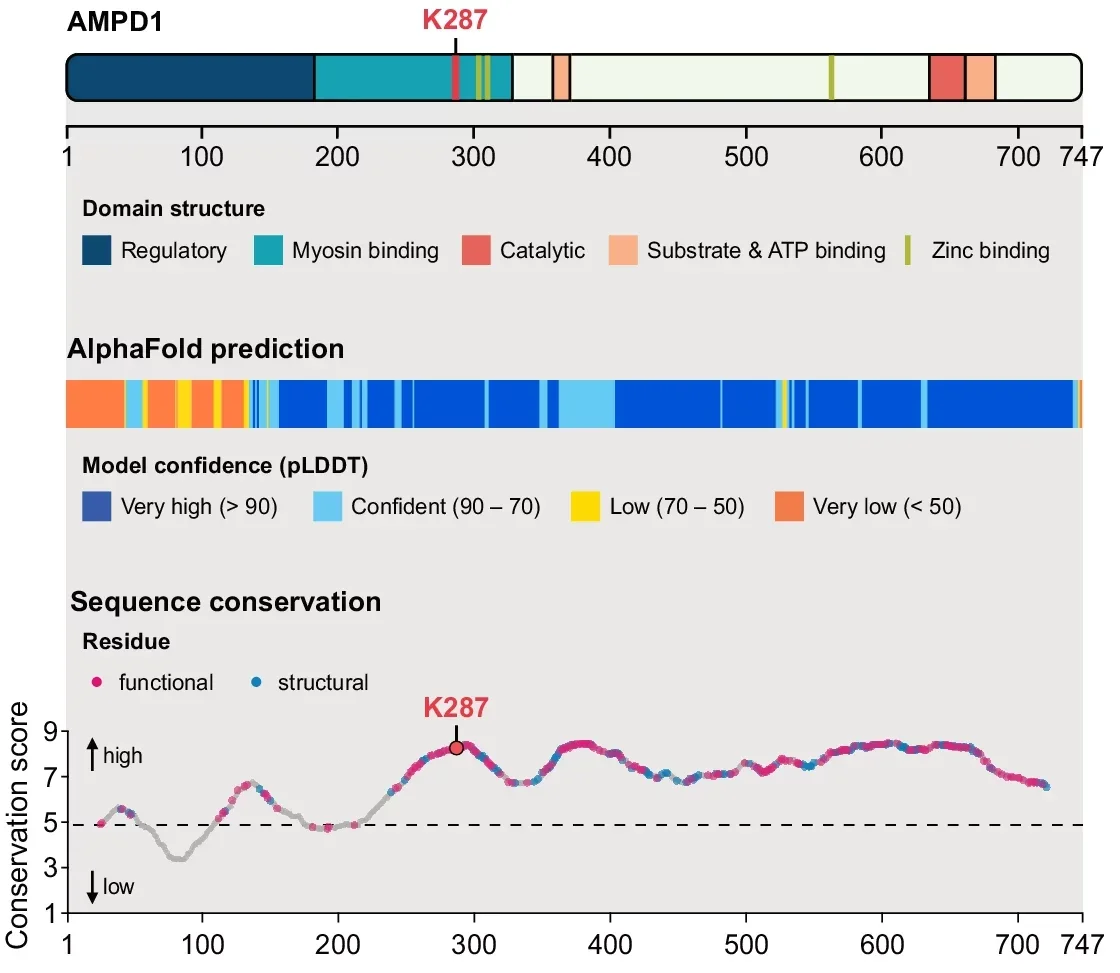

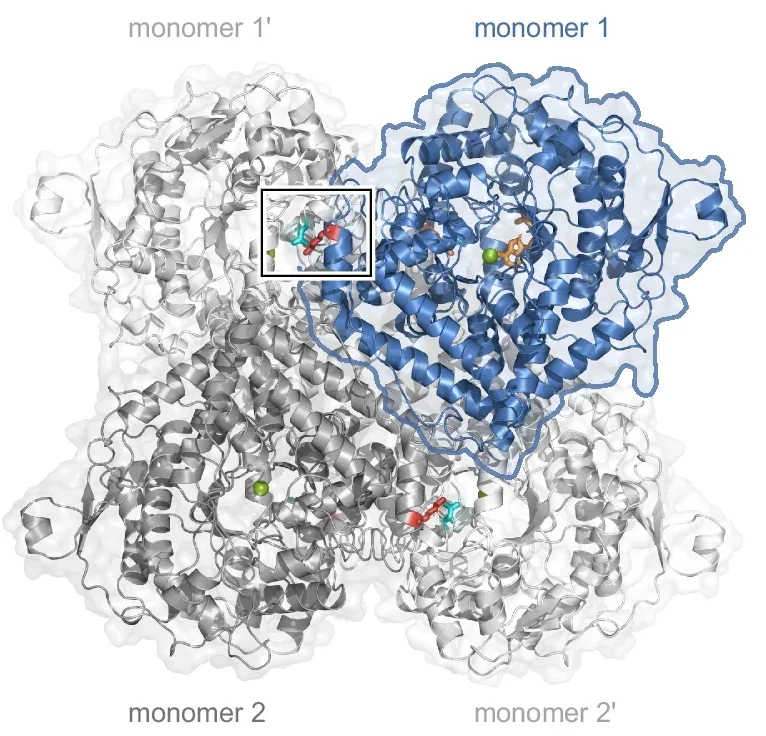

AMPD1 plays a central role in muscle energy production. The Neanderthal version swaps just one building block in the enzyme, yet that small change matters. When researchers recreated the Neanderthal enzyme in the lab, its activity dropped by about 25 percent compared with the modern human version.

To see what that means in a living body, the team engineered mice to carry the same change. In muscle tissue, enzyme activity fell by about 80 percent. That sharp decline confirmed the Neanderthal version works far less efficiently.

“Strikingly, most individuals who carry the variant do not experience significant health issues,” said Dominik Macak, the study’s first author. “However, the enzyme appears to play an important role in athletic performance.”

Neanderthals lived across Europe and western Asia before meeting modern humans around 50,000 years ago. When the two groups interbred, some Neanderthal genes entered the modern human gene pool. Today, people of non-African ancestry carry about one to two percent Neanderthal DNA.

The weakened AMPD1 variant is one of those inherited traits. It now appears in about two to eight percent of Europeans and at lower levels in some South Asian and Native American populations. Genetic analysis showed the surrounding DNA is too long to have survived from a shared ancient ancestor. Instead, it clearly came from Neanderthals.

To understand real-world effects, the researchers looked at data from more than a thousand elite athletes. They focused on AMPD1 variants that reduce enzyme function, including a common modern mutation that fully disables the enzyme.

The pattern was clear. Athletes were far less likely to carry these variants than non-athletes.

“Carrying a broken AMPD1 enzyme, the likelihood of reaching athletic performance is reduced by half,” Macak said.

This effect showed up in both endurance sports, like distance running, and power sports, like weightlifting. Under everyday conditions, the enzyme may not matter much. Under extreme physical stress, it does.

The team also explored medical records from large biobanks. People with reduced AMPD1 activity showed a slightly higher risk of vein problems, including varicose veins. The increased risk was modest, about three to six percent, but consistent across datasets.

A few rare individuals who carried two different damaging AMPD1 variants reported chronic muscle pain, cramps, and exercise intolerance. These cases suggest the enzyme can become important when its activity drops too low.

The researchers believe AMPD1 faced relaxed evolutionary pressure in both Neanderthals and modern humans. Senior author Hugo Zeberg offered one explanation.

“It’s possible that cultural and technological advances in both modern humans and Neanderthals reduced the need for extreme muscle performance,” he said.

Better tools, cooperation, and food strategies may have lowered the survival cost of weaker muscle energy systems. As a result, variants that reduce AMPD1 activity could persist without major harm.

This work shows how ancient DNA can help explain modern differences in strength, endurance, and disease risk. It highlights why some people struggle more with intense exercise while remaining healthy in daily life.

For medicine, it offers clues about muscle disorders and vein disease.

For science, it shows the value of studying genes in both evolutionary and physiological context.

Understanding where these variants came from helps explain why they still exist and when they matter most.

Research findings are available online in the journal Nature Communications.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Neanderthal enzyme appears to play a significant role in athletic performance appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.