Astronomers at the University of Alabama in Huntsville may have found the closest evidence yet of a hidden clump of dark matter near the Sun. Led by astrophysicist Sukanya Chakrabarti, the research team reports that an unseen mass appears to be gently tugging on nearby pulsars. The findings were published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Dark matter has never been observed directly. However, scientists estimate that dark matter is responsible for approximately 85 percent of the total amount of matter present in the universe. The principal cosmological model predicts that galaxies similar to the Milky Way are enveloped within enormous halos of dark matter.

These halos themselves contain smaller accumulations of dark matter referred to as subhalos. Despite many years of attempts, no dark matter subhalo has been definitively located in our own galaxy. This recent research provides one possible clue as to where to look for such a mass.

To perform this research, the scientists used an uncommon type of instrument: pulsars. Pulsars are neutron stars that are rotating very rapidly and give off beams of radiation, making them similar to lighthouses in space. As the beams of light produced by a pulsar sweep across the surface of the Earth, they do so with mechanical precision, and some pulsars are as accurate as atomic clocks.

As a result, pulsars are perfect candidates for studying the effects of gravity. When a pulsar speeds up or slows down along your line of sight, the timing of the pulsar’s pulses will change very slightly. By studying those changes, a researcher can measure how the force of gravity is currently acting on a pulsar.

Chakrabarti and her collaborators have been focusing on binary pulsars. A binary pulsar consists of a pulsar that is revolving around another star, generally a white dwarf star. The orbital period of the pulsar in these systems changes over time.

For example, if a researcher observes a pulsar that is moving closer to the observer, the orbital period will shorten. The movements of a pulsar, along with its energy loss from gravitational waves, combine to create a drift in the pulsar’s timing.

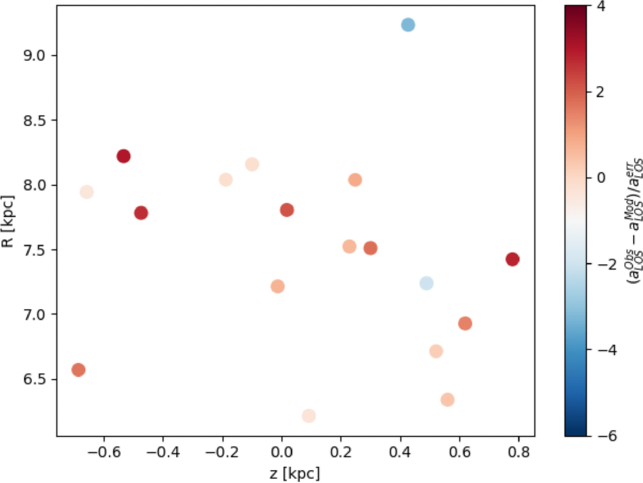

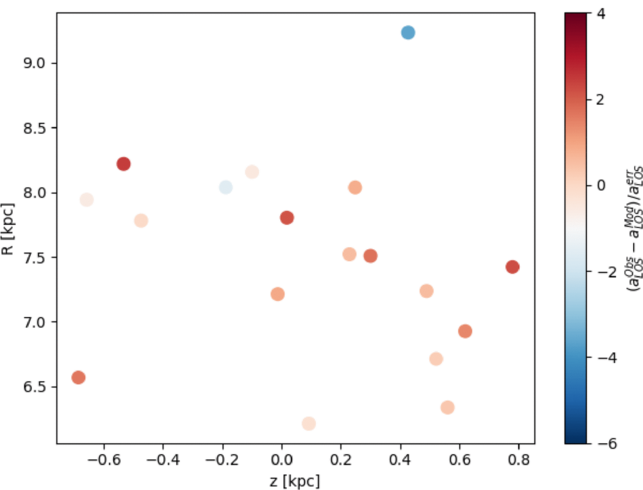

When the effect of pulsar motion and energy loss from gravity has been eliminated, researchers are left with how much gravity from our galaxy was acting on that pulsar. By measuring the acceleration that is felt by the pulsar from the Milky Way, scientists can determine the acceleration due to gravity from the galaxy itself.

Therefore, pulsars can essentially be used to determine how much gravitational acceleration exists within the Milky Way.

Typically, scientists believe that the gravitational pull of the Milky Way is smooth and consistent throughout the galaxy. However, this group of scientists did not accept this premise. They wanted to know whether the existence of small, localized gravitational pulls near the Sun could affect pulsars.

These small localized pulls may have been caused by dark matter subhalos, which are predicted to exist. When researchers find one pulsar exhibiting an unusual acceleration, there could be a variety of causes that explain the difference. However, when multiple pulsars that are less than 1,600 light-years from each other all show the same unusual acceleration, it becomes considerably more difficult to dismiss.

There were 27 binary pulsars with suitable timing data, and each had its properties studied using pairs of binaries less than 1,600 light-years from each other. This distance is consistent with what has been postulated to be the probable area of influence from a dark matter subhalo.

Among the many pairs, two pulsars stood out. J1640+2224 and J1713+0747 were shown to both experience a common source of acceleration that was greater than what could be explained by normal stellar matter. Both pulsars are located relatively close to the Sun and are found in binary systems.

One pulsar is in a binary system with a white dwarf companion. Researchers sought to identify an ordinary matter source for the signal using star counts from Gaia data and gas cloud surveys from hydrogen, but they found nothing that could account for the effect.

From the measured size of the acceleration, the researchers estimated that an unseen object with approximately 25 million solar masses is located just a few thousand light-years away from Earth. This places it within the range predicted for dark matter subhalos.

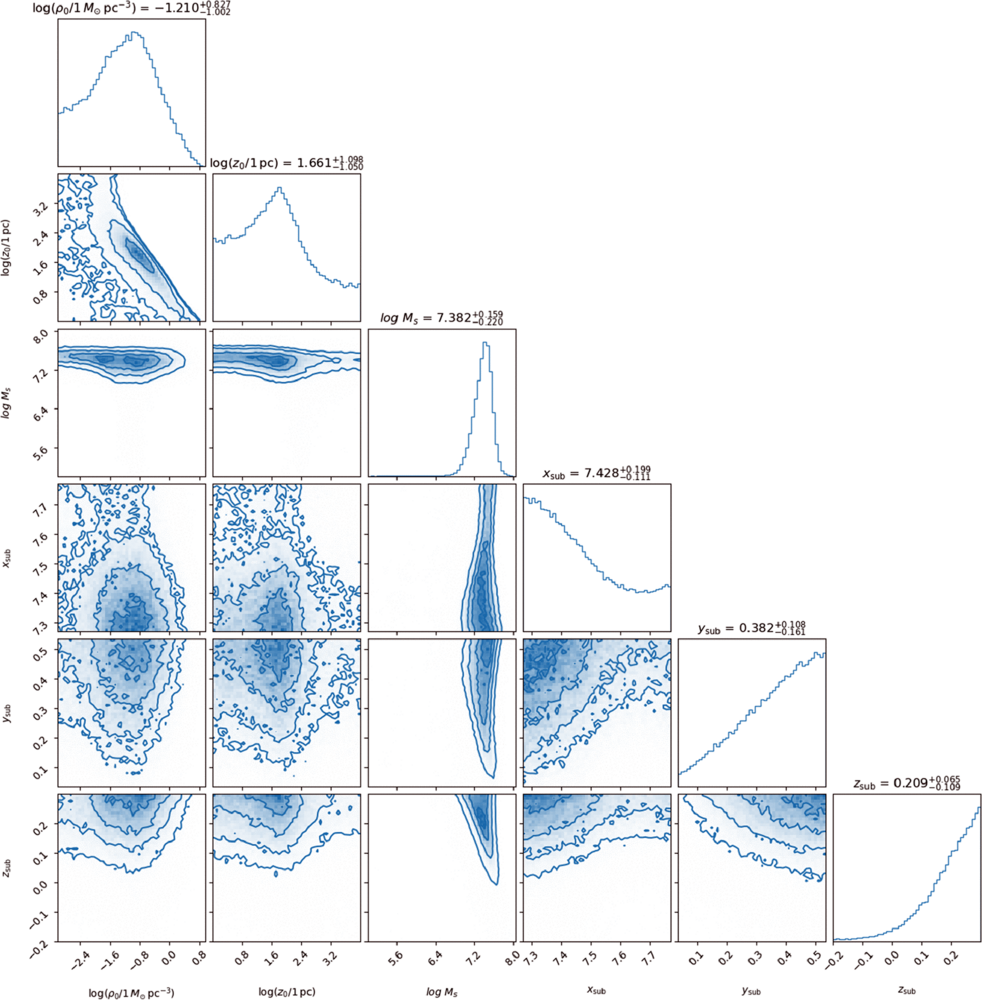

To further investigate, the researchers included additional nearby pulsars, including solitary and binary systems. They also conducted various statistical analysis techniques, which confirmed the previous results. Although the exact position of this object remains uncertain, the mass is now much more tightly constrained.

The researchers also investigated the effects of different geometric shapes for the hidden mass. Whether it is a point mass or a more dispersed geometry, the data still favors the existence of additional mass. Comparisons between models using statistical methods indicate moderate to strong corroboration for dark matter.

The researchers have also provided strong evidence against the possibility that this object is composed of ordinary matter. If tens of millions of solar masses were concentrated into such a small volume, the density would have to be extremely high compared to other material found near the Sun, such as stars and gas.

The density of normal matter in this area is more than 100 times lower than the areas measured by Gaia. Gaia measurements do not show an excess of stars in this region, and no gas surveys provide evidence that could explain the signal. This leaves dark matter as the only viable candidate.

The researchers are cautious. The Milky Way has not been stable in the past and has interacted with dwarf galaxies, resulting in structural ripples throughout the galaxy. The effects of these past interactions may produce differences in gravitational strength across large areas of space.

Although the signal detected in this study appears to be localized rather than spread throughout the galaxy, more data will be needed to confirm its existence. The method of measuring pulsar timing will continue to produce better results over time and will continue to provide researchers with more certain results.

The research team encourages the use of additional high-precision techniques to examine this region of space. Continued observations will help determine whether the signal persists or fades with more data.

If confirmed, this would represent the first detection of a dark matter subhalo within the Milky Way galaxy. Such a discovery would mark an important step toward understanding how dark matter exists at very small scales. It would also help close long-standing gaps between theoretical models and observational data for galaxy formation.

The technique used in this research may be just as significant as the discovery itself. Using pulsars as direct probes for measuring gravitational acceleration provides a new way to map invisible mass without assuming a specific distribution or symmetry.

As pulsar timing measurements continue to improve, many more dark matter structures may be revealed. Over time, mapping dark matter clumps near Earth could significantly improve models of cosmic evolution and guide future efforts to uncover the fundamental nature of dark matter, one of the most persistent unanswered questions in physics.

Research findings are available online in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The original story “Astronomers find clearest evidence yet of a dark matter subhalo near the Sun” is published in The Brighter Side of News.

Like these kind of feel good stories? Get The Brighter Side of News’ newsletter.

The post Astronomers find clearest evidence yet of a dark matter subhalo near the Sun appeared first on The Brighter Side of News.

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.